Barbara Bradley, an editor with the Memphis Commercial Appeal, moved into the River City’s reviving downtown about a year and a half ago, loving its “energy and enthusiasm.” But a horde of invading panhandlers has cooled her enjoyment of city life. Earlier this year, she recalled in a recent column, as she showed some visitors around the neighborhood, “a big panhandler blocked the entrance to our parking area and demanded his toll.” Now a nervous Bradley avoids certain downtown areas, locks her car when fueling up at local gas stations, and parks strategically, so that she can see beggars coming before getting out of her car. “When I hear someone call out ‘ma’am, ma’am’ anywhere in downtown or midtown, I run.”

She’s not alone. Cities have overcome myriad obstacles in revitalizing their downtowns, from lousy transportation systems to tough competition from suburban shopping malls. But nearly 15 years after New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his police chief, William Bratton, vanquished Gotham’s notorious squeegee men and brought aggressive panhandling under control, other cities are facing a new wave of “spangers” (that is, spare-change artists) who threaten their newfound prosperity by harassing residents, tourists, and businesses. Unlike their predecessors in the seventies and eighties, many of these new beggars aren’t helpless victims or even homeless. Rather, they belong to a diverse and swelling community of street people who have made panhandling their calling.

Like most countries, America has always had its share of itinerant travelers, vagabonds, and hoboes. But panhandling became a more pervasive and disturbing fact of urban life in the 1970s—a by-product of the explosion in homelessness that resulted from rising drug use and the closing of state-run mental institutions, which released scores of helpless psychiatric patients back into society. Though studies showed that only a small percentage of homeless people panhandled—mostly alcoholics and drug addicts seeking their next fix—the sheer numbers of street people still meant lots of beggars. By the crack epidemic’s late-eighties peak, New York City in particular was home to a massive panhandling presence. A 1988 survey by New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority found that 80 percent of subway riders disliked the constant harassment. “I was raised never to pass a beggar by, but there are too many of them and I’m sick of it,” one Manhattanite told the New York Times. “I feel like this is becoming beggar city.”

The problem soon turned from irritating to alarming in “beggar city,” as incidents of aggressive panhandling leading to violent crime began showing up regularly in the headlines. In 1988, an itinerant panhandler on Manhattan’s Upper West Side murdered his girlfriend’s three-year-old daughter, whose dead body he then stuffed into a baby carriage and took out on his rounds, along with the girl’s still-living brother. A year later, an aggressive panhandler stabbed to death a 32-year-old computer engineer in a confrontation on West 114th Street in Manhattan. Shortly after, in the Bronx, an 18-year-old boy died from stab wounds inflicted by a panhandling immigrant who knew just four English words: “Give me a dollar!”

The escalation—and other cities faced it, too—shouldn’t have been surprising. “If the neighborhood cannot keep a bothersome panhandler from annoying passersby . . . it is even less likely to call the police to identify a potential mugger or to interfere if a mugging actually takes place,” wrote political scientist James Q. Wilson. One change in policing that had contributed to the growing disorder, observed Wilson, was curtailing foot patrols in favor of squad cars. In the past, an officer on the beat would discourage panhandlers; now he just drove on by.

New York, fed up with the disorder, began to crack down on panhandling in the early nineties. The effort started in the subways, spearheaded by the Bratton-led Metropolitan Transit Authority police, who combined policing with outreach efforts for homeless beggars willing to come in off the streets. The cleanup continued when Bratton became Giuliani’s first police commissioner in 1994 and took on the squeegee men—insistent panhandlers who intimidated Manhattan drivers by washing their car windows and then demanding payment. After a study by criminologist George Kelling found that three-quarters of the squeegee men weren’t homeless and that half had felony records, cops began arresting them for blocking traffic. That put an end to the shakedowns in a matter of weeks.

The city then extended the anti-panhandling campaign to other parts of the city, including beggar-dominated Times Square. Central to the crackdown was the Midtown Community Court, an experimental judicial body to which police could drag quality-of-life arrestees the very day they issued citations. Working with social-services providers who offered help to those needing it, the court acted with lightning speed, usually giving community-service sentences to those willing to plead guilty to misdemeanor charges, so that someone arrested for panhandling in the morning could be cleaning the neighborhood by the afternoon. The immediate results gave police a strong incentive to enforce the city’s long-moribund quality-of-life statutes; previously, if an officer issued a quality-of-life citation, the panhandler had a month or longer to respond to the summons and often didn’t show up in court on the appointed day. As with the subways and the squeegee men, the campaign was a huge success.

Other cities, following New York’s lead, worked to reduce their own (much less severe) panhandling blight during the nineties—adopting community courts, forcing beggars to register for licenses (which discouraged them), and passing new anti-panhandling laws. These measures, though rarely as tough as Gotham’s, helped spark new development and interest in downtown districts across the country.

But over the last several years, the urban resurgence has proved an irresistible draw to a new generation of spangers. And while New York City’s aggressive emphasis on quality-of-life policing under two successive mayors has kept them at bay, less vigilant cities have been overwhelmed. Indeed, panhandling is epidemic in many places—from cities like San Francisco, Seattle, Austin, Memphis, Orlando, and Albuquerque to smaller college towns like Berkeley. “People in New York would be shocked at what one encounters in other cities these days, where the panhandling can be very intimidating,” says Daniel Biederman, a cofounder of three business improvement districts in Manhattan, including the Grand Central Partnership, which grappled effectively with homelessness in the city’s historic train station in the early 1990s. “Panhandling has gotten especially bad in cities that have a reputation for being liberal and tolerant. They have tried to be open-minded, but now many of them see the problem as out of control.”

A big part of the cities’ woes is the professionalization of panhandling. The old type of panhandler—a mentally impaired or disabled homeless person trying to scrape together a few bucks for a meal—is giving way to the full-time spanger who supports himself through a combination of begging, working at odd jobs, and other sources, like government assistance from disability payments. Some full-time panhandlers are kids—“road warriors” who have largely dropped out of society and drift from town to town, often “couch surfing” at friends’ homes, or “street loiterers” who daily make their way downtown from the suburbs where they live. Some, like New Yorker Steve Baker, have turned begging into a full-time job. “If you’re inside a bank, you’re a doorman,” he says from his perch inside a bank lobby. “You’re not gonna rob from nobody or steal from nobody—you come in here and make a job for yourself.”

People’s generosity encourages the begging. About four out of ten Denver residents gave to panhandlers, city officials determined several years ago, anteing up an estimated $4.6 million a year. Anecdotal surveys by journalists and police, and even testimony by panhandlers themselves, suggest that begging can yield anywhere from $20 to $100 a day—though police in Coos Bay, Oregon, found that local panhandlers were taking in as much as $300 a day in a Wal-Mart parking lot. “A panhandler could make thirty to forty thousand dollars a year, tax-free money,” Baker says. In Memphis, a local FOX News reporter, Jason Carter, donned old clothes and hit the streets earlier this year, earning about $10 an hour. “Just the quasi-appearance of being homeless filled my cup,” Carter observed. That all the money is beyond the tax man’s clutches adds to the allure of professional panhandling.

Carter prepared for his stint on the street by surfing the Internet, where a variety of websites dispense panhandling advice. NeedCom, for example—subtitled “Market Research for Panhandlers”—offers tips from Baker and other pros on how to hustle. The website’s developer, Cathy Davies, wants it to get people “thinking about panhandling as a realistic economic activity, rather than thinking that panhandlers are lazy or don’t work very hard.”

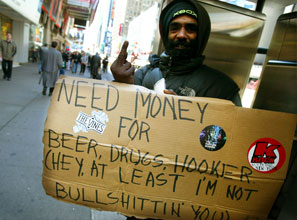

The rise of online panhandling advice helps explain why panhandlers and “sign flyers”—beggars who use signs to solicit donations—exhibit remarkably similar methods around the country. Currently, the direct, humorous approach is in vogue. That’s why in many cities today you’ll hear some version of: “I won’t lie to you, I need a drink.” Panhandlers also report that asking for specific amounts of money lends credibility to pitches. “I need 43 more cents to get a cup of coffee,” a panhandler will declare; some people will give exactly that much, while others will simply hand over a buck.

If it seems unlikely that a homeless person would surf the Web for advice on how to panhandle, that’s exactly the point: many aren’t homeless and are lying about their circumstances. A reporter for KUTV in Salt Lake City followed and filmed panhandlers for several months, documenting their scams. One twentysomething woman wielded a sign informing people that she was homeless and needed a bus ticket back to Seattle. The reporter followed her one day, however, and discovered that she lived in a nearby suburb. Confronted by the reporter, the woman explained away her deception: “I don’t say anything to anybody. I hold this sign. I don’t make anybody give me money.” Her story isn’t unique: homeless advocate Pamela Atkinson told KUTV that some 70 percent of panhandlers in Salt Lake City aren’t describing their situations accurately.

Like their counterparts back in the eighties, some spangers refuse to take no for an answer. Aggressive begging has grown so common in Memphis that a group of residents, members of an online forum called Handling-Panhandling, have begun photographing those who act in a threatening manner, seeking to help police catch those who violate the law. “One of the guys we photographed for the Handling-Panhandling group last summer was obviously a loose cannon,” forum host Paul Ryburn writes. “When employees of a Beale Street restaurant asked him to stop begging in front of their door, he threatened to stab them.”

Reports of similar incidents are on the increase in many cities. A pizzeria manager in Columbus, Ohio, told the Columbus Dispatch earlier this year that panhandlers were entering the store asking for money, then following women back to their cars to scare them into giving it. “One of the bums threatened to stab me when I asked them to leave two women alone,” the restaurateur added. In Orlando, panhandlers have started entering downtown offices and asking receptionists for money, prompting businesses to lock the doors. San Francisco police have identified 39 beggars who have received five or more citations for aggressive panhandling, racking up a total of 447 citations. Tourist guidebooks and online sites are replete with warnings from travelers. A business visitor to Nashville, sharing his experiences on Fodor.com, writes: “Every day I was there I was not just approached but grabbed or touched by folks asking for money.” A traveler to San Francisco, describing his trip on Virtualtourist.com, warns prospective tourists about the pervasiveness of persistent beggars: “If you come to San Francisco and are not hit up for change, you have spent too much time in your hotel room.”

Widespread begging bears much of the blame for lingering public impressions that downtowns remain unsafe, even in places like Minneapolis, where crime has fallen. In a survey last year, more than a fifth of Minneapolis’s downtown workers called the area “extremely unsafe” in the evening, largely because of extensive panhandling (nine out of ten downtown workers report getting asked for money at least several times a month). Aggressive beggars have tried to extort cash from waitresses at local restaurants by threatening to harass customers. Families visiting downtown report panhandlers following them down the street and cursing at them if they refuse to give, according to the head of the Downtown Council, a local business group. The bullying shakedowns are having an economic effect on the city: some firms have balked at renewing leases. Downtown business owners in Nashville now rank panhandling as their Number One problem.

In St. Louis, another city battling perceptions that it’s dangerous, two-thirds of respondents to an online poll by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said that they’d encountered aggressive panhandling. Matt Kastner, a real-estate agent who has moved back to St. Louis from the suburbs, believes that panhandlers are perpetrating much of the minor crime—such as car break-ins—that plagues parts of St. Louis. Many solicit him on the city’s roads. “They’ll come right at the car as you’re getting off an exit ramp,” he says. “I’m afraid one of these days I’m going to hit one of them.” Kastner’s fears aren’t misplaced: in Austin, where persistent begging has given new meaning to the term “Texas panhandle,” the police chief noted last August that more than a third of the people killed in traffic accidents that year had been cited for begging in the past.

Confronting the new panhandling plague, many cities have been hamstrung by local factors that have made it hard to attack the problem in the aggressive, enforcement-driven New York style. Some places, for instance, never transformed their police forces to emphasize quality-of-life crime and the importance of the cop on the beat. Certain states, such as California, prohibit community courts for misdemeanors. And sometimes a city’s political tradition is so liberal that the notion of cracking down at all is anathema. When Seattle city attorney Mark Sidran proposed muscular anti-panhandling restrictions in the early 1990s, protesters burned him in effigy; today, despite complaints from visitors, Seattle pols still have no real plans to deal with the new wave of panhandling. Anti-panhandling efforts in Oregon and other states also have run into legal obstacles from state courts, which have broadly interpreted begging as a protected form of free speech and shot down new laws curtailing it.

Still, some locales, while not going to New York’s lengths, are experimenting with innovative ways to curb panhandling. Orlando allows begging only in “panhandling zones,” demarcated by blue boxes painted on the sidewalks in several locations. A more common response has been to educate the public about panhandling and to offer alternative ways to help those who really need it. The Nashville Downtown Partnership, for instance, has launched a publicity campaign, “Please Help, Don’t Give,” which explains through posters that money given to panhandlers often supports drug and alcohol addictions. The partnership asks people to donate instead to organizations that provide local services.

Denver’s anti-panhandling initiative seems particularly promising. The city has turned 86 old, unused parking meters into donation boxes and placed them around downtown. The meters allow people to give directly on the street, where they’re likely to encounter panhandlers, assuring donors that their money will go to programs to assist the truly needy. “$1.50 provides a meal for a homeless person,” the meter proclaims. Between donations and corporate sponsorship, the meter program is generating about $100,000 a year, distributed to local groups to provide housing, job training, and other services, says Jamie Van Leeuwen, head of the city’s homelessness-combating Road Home program. The meter initiative is also deterring spanging—the city estimates that it’s down a striking 90 percent. “Panhandling and homelessness are not synonymous,” says Van Leeuwen. “Our homeless underscore that just because they are homeless, that does not mean that they panhandle.” Several cities are already copying the Denver initiative, including Chattanooga, which calls its version “The Art of Change,” and Minneapolis; others, like Las Vegas, are considering it.

Cities are also coming up with new anti-panhandling legislation designed to pass muster in the courts. Several cities have passed “sit, lie” ordinances, for example, which say nothing about panhandling but ban people from sitting or lying on streets and sidewalks. Portland officials proposed a “sit, lie” law and then won over local homeless advocates by promising new spending on services for the truly needy. “In Portland, only about 10 percent of the people loitering on downtown streets and begging during the day were homeless,” says Mike Kuykendall, president of the city’s downtown business improvement district. He credits the anti-panhandling initiative with playing a part in a 29 percent decline in street crime downtown over the last three years.

Similarly, several cities and smaller communities have banned motorists from giving to beggars, framing the legislation as safety ordinances. Courts have also upheld laws that prohibit beggars from touching people without their consent, intentionally blocking their path, and using obscene or abusive language.

Yet even as cities experiment with new approaches, those traditionally opposed to restrictions on panhandling are fighting back—notably, civil liberties groups and some homeless advocates, who oppose any actions that might criminalize conduct by even a minority of the homeless. In 2003, San Francisco residents overwhelmingly passed a ballot proposition authored by then-supervisor (and now mayor) Gavin Newsom outlawing in-your-face panhandling. But the ordinance has been ineffective because scores of volunteer lawyers, many from the city’s biggest law firms, have fought every citation. People cited for panhandling don’t even need to appear in court. They simply drop their citations in boxes at various advocacy groups, and the lawyers pick them up and appear in court, where judges have ruled that cops must file lengthy reports in order to get a conviction. The courts are dismissing about 85 percent of all tickets handed out under the ordinance, frustrating police, prosecutors, politicians, and residents who voted for it. “If you had been here several years ago, before the ordinance passed, and came back today, you wouldn’t see a difference in the level of panhandling. There’s as much as ever,” says supervisor Sean Elsbernd.

Such battles between civil libertarians and those who want to limit panhandling remain common. Austin civil rights advocates got the city’s ban on panhandling along roadsides overturned; the court ruled that the city hadn’t adequately demonstrated that panhandling was a safety issue. Even New York City, which has long been able to stave off court challenges to its panhandling ordinance, isn’t immune. A local judge has ruled that police have sometimes overstepped the bounds of the city’s aggressive panhandling legislation and arrested people for peaceful solicitation. Last year, a court awarded $100,000 to a beggar arrested eight times in the Bronx.

But there’s no doubt that some cities have been more effective than others at building anti-panhandling campaigns. “I recently visited New York City and was shocked to discover that for a city with ten times our population, it has one tenth as many beggars,” one San Franciscan wrote on the San Francisco Chronicle’s website. “The few I did see sat silently with their signs and said nothing. I didn’t witness a single instance of aggressive panhandling. The reason for this? The city passed laws against such conduct and has enforced those laws. If it can work over there, it can work here.”