Since the late 1990s, more than 18 police commanders have left the New York City police department to run their own agencies elsewhere. This unprecedented migration has spread the Compstat revolution—the data-driven transformation of policing begun under New York police commissioner William Bratton in 1994—across the nation. Some of the transplants are well-known: Bratton himself now heads the Los Angeles Police Department; and his former first deputy, John Timoney, has led both the Miami and the Philadelphia forces. But the diaspora also includes lesser-known young Turks who rose quickly through the NYPD’s ranks during the paradigm-shattering 1990s. Now, as chiefs in their own right, they’re proving the efficacy of analytic, accountable policing in agencies wholly dissimilar from New York’s—in one case, achieving success beyond anything seen in Gotham or elsewhere.

José Cordero once led precincts in the Bronx and in Manhattan’s Washington Heights, and eventually he served as New York’s first citywide gang strategist. Like other members of the diaspora, he describes the 1990s NYPD as a life-changing experience: “It was an incredibly resourceful, competitive environment. The wave of captains I was privileged to serve with fed off of each other’s experiments.” In 2002, he took the helm of the Newton, Massachusetts, police department, bringing crime in that already safe city down to its lowest point in over 30 years.

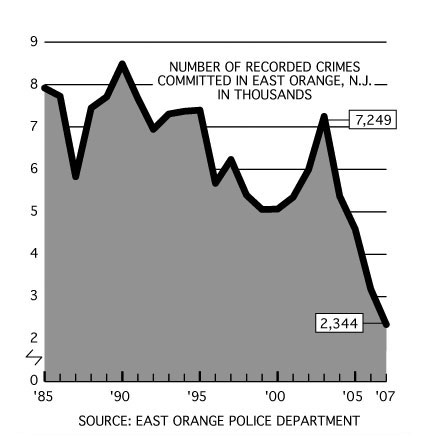

Then he moved to a very different city. East Orange, New Jersey, has 70,000 citizens by official counts, about 95 percent of them black, and deep pockets of poverty. Crime there—much of it violent—had started skyrocketing in 1999, reaching a per-capita rate in 2003 that was 14 times that of New York City and five times that of Detroit. East Orange’s mayor recruited Cordero to quell the violence; Cordero started work in 2004. The results were astonishing. By the end of 2007, major felonies had dropped 68 percent, and homicides 67 percent, from their 2003 high—possibly a national record. (By comparison, from 1993, the year before Bratton arrived in New York City, through 1997, major felonies in New York dropped 41 percent and homicides 60 percent.) East Orange’s remarkable experience should give pause to criminologists, who too often ascribe crime drops to anything but policing reforms.

If the true test of a leader is his ability to imbue an organization with his vision, Cordero has leadership skills in spades. Intelligence-driven policing, as he calls the Compstat principles, is now in the department’s bloodstream, as is the still-iconoclastic belief that the police can actually lower crime. Compstat refers both to the weekly crime-analysis meetings that Bratton pioneered in 1994 to grill precinct leaders about crime on their watch and, more broadly, to the crime-fighting principles that underlay those meetings: relentless gathering of information, constant evaluation of tactics, and a mechanism for holding commanders accountable for public safety. East Orange commanders now focus obsessively on their mission and revel in coming up with new ways to make the city inhospitable to criminals.

The transformation that Cordero effected in the East Orange department mirrored the one he had lived through as a young NYPD captain at the dawn of Compstat. “All we had done up to that point was put people in jail, and it hadn’t made a difference,” recalls the 52-year-old Bronx native. “The new concept was, know everything you possibly can about crime. What I took away from that period was that by challenging yourself continually to know what you don’t know, you can produce big results.”

So Cordero tasked his new team to find out everything it could about who was shooting whom. He combined East Orange’s gang and narcotics squads to maximize information-sharing between drug and gang detectives, since the narcotics trade and gang violence entwine so closely. Eventually, the department targeted the most violent drug dealers and drove them out of business. Word got out on the street that if you engaged in a shooting, not only were you going to do time—possibly in the federal slammer—but your whole criminal enterprise would be shut down.

Weekly Compstat meetings are at the core of the East Orange crime rout, but Cordero, like his expatriate peers, borrows freely from the entire gamut of crime-busting techniques developed in New York. He put East Orange’s two most dangerous streets under 24-hour lockdown for six months while the police bore down on the dealers, a strategy that his NYPD colleague (and now Newark top cop) Garry McCarthy had successfully pioneered in Washington Heights. Today, those two streets are clean and orderly.

Ronald Borgo exemplifies the East Orange Police Department’s transformation. He exudes enthusiasm as he sits at a computer terminal, putting the turbocharged crime-analysis computer program that Cordero designed through its paces. “I was ready to move on until I saw what Director Cordero brought on board,” says the barrel-chested 27-year veteran of the department, who is soon to be confirmed as chief (a position underneath director). “I’m embarrassed to say that in 2000, we didn’t know how to connect the dots. We were just reacting to crime. The director gave us the knowledge and the confidence to actually fight it.”

However much Cordero and Borgo stress that it is managerial and philosophical change, not fancy gadgets, that has driven crime down, it’s hard not to be wonderstruck by that computer program—“Compstat on steroids,” as Cordero calls it. Its “crime dashboard” graphically presents layer upon layer of real-time crime and policing information, updated every 30 seconds. Commanders can check whether any sector of the city is meeting its daily, weekly, and monthly crime-reduction targets, and how the sector’s record stacks up against last year’s numbers. They can instantly pull up a history of the crimes committed at any location, along with every police response to those crimes, in order to evaluate what strategies have or have not succeeded there in the past. Users can activate the city’s public cameras to display crime hot spots.

And most unusually, users can observe how every patrol car is deployed at that moment and what it is doing to prevent crime, in what the department calls “directed patrol.” Directed patrol is really nothing more than what good beat cops used to do as a matter of course, before the 911 radio car swallowed their jobs: rather than simply cruising around town waiting for trouble to happen, an officer is supposed to use his time to preempt crimes, ideally by getting out of his car. Cops might walk up a housing project’s stairwell to check for drug dealers, say, or pass out flyers about a robbery spree at a mini-mall. “You’d be surprised what people will tell you when you’re out of your car that they won’t call the department about,” says Borgo—such as that a neighboring apartment is likely dealing drugs. Institutionalizing the concept of directed patrol represents a “huge organizational change in how officers work on the street,” says Lieutenant Chris Anagnostis. “The new model is: when a cop is not answering a radio call, he should be back in his zone engaged in proactive policing.”

The real-time display of patrol activity allows managers to monitor deployment patterns as well as officer initiative. “If a citizen reports a problem, and an officer doesn’t see and act on it, then it becomes clear to me that he is not enthusiastic about his job,” says Cordero, who dismisses the suggestion that the oversight may feel Orwellian to a street cop. “We’re not looking to see if an officer is having a cup of coffee. We’re in the business of protecting people; any good cop will see the value of that. For those that don’t, I have a word for them: ‘Tough. Find another line of work.’ ”

The patrol-car locator system did produce a backlash. Some officers broke their cars’ antennae or yanked out the requisite communication wires. Cordero remained unfazed: “There’s 70,000 people I care about; I don’t fear disgruntled cops.” He seems to have won the battle—officers now treat the vehicle locators as a matter of course. And self-initiated activity has gone way up, reports Borgo. “In 2004, we did 6,389 directed patrols and we thought we were working. In 2007, we did almost half a million,” he says. “The technology is one thing, but these cops, my cops, are working. I’m so proud of these cops.”

After the department introduced the crime dashboard in 2005, crime plummeted 26 percent in one year. Currently, only supervisors at headquarters and in the field have access to the dashboard, but eventually, every officer on the beat will have a simplified version in his car, so that he can monitor crime in the city in real time and see how his colleagues are responding.

The crime dashboard was just the start of East Orange’s technology boom, which has cost about $1.5 million, paid for with federal and state grants and criminal forfeiture money. On the two streets that had been locked down, the department gave residents computer programs enabling them to report suspicious conditions by pointing their mouses at street photos. Community patrol officers have “virtual directed patrol” screens in their cars that let them watch two places simultaneously: they can park at a drug corner to deter dealing, for instance, while calling up camera shots of other high-crime locales throughout the city. Back at the station house, a detective rides the same public camera system, zooming in on a license plate, say, to see if a car is stolen or if its driver is wanted on an outstanding warrant. Borgo is even building a room in the reception area with 42 large screens that will display live shots from all over the city—a public display of the department’s surveillance capacities, which criminals already falsely believe are all-encompassing. “And I’m going to get civilians to monitor them: they see as well as people in uniform,” he adds slyly.

Gunshot-detection sensors at various locations alert headquarters immediately when a gun gets discharged outdoors. Cameras then take pictures around the source of the shot, with an emphasis on roads and nearby arteries leaving the city, since in 70 percent of East Orange shootings, someone zooms off afterward in a car. The department also plans to introduce license-recognition technology that will automatically tell the police when a stolen car has entered the city.

Bratton famously drew on business principles to transform the NYPD bureaucracy into a crime-fighting machine—a bottom-line orientation that Cordero has absorbed as well. “You have to treat this business as if it were your own,” he says. “A Fortune 500 company is in the business of making money; we’re in the business of saving lives. Can I survive a year without a return on my investment? Maybe. Five years? No.” Cordero regards the public as the consumers of policing services. “We don’t accept excuses when we’re shopping if any item is not available; we expect supply to be consistent with demand,” he points out. “The public should not accept excuses from the police.”

Moreover, Cordero argues, a police department must respond to what consumers actually want from it, not to what it thinks they should want. The two things are not necessarily identical, as Broken Windows theorists point out and police departments discover time and again. “In the South Bronx, we took out the gangs; violence plummeted,” he recalls. “I expected kudos, but instead people asked what we were doing about stolen cars, prostitution, and Saturday night boom boxes.” Consistent with his business-service model, Cordero started sending civilian inspectors to East Orange households where officers had answered 911 calls, to poll residents about the officers’ performances. These audits, like the directed patrols, were initially unpopular among some members of the rank and file but are also now regarded as routine.

Crime continues to fall in East Orange, half a year after Cordero left the department to become New Jersey’s first gang-violence czar and bring intelligence-driven policing to the entire state. As of mid-June 2008, crime in East Orange was down another 15 percent over the same period in 2007, even as violence remains high in perennially murder-torn cities like Camden.

And the sense of urgency about crime-fighting, which it is the Compstat mechanism’s supreme accomplishment to institutionalize, has not abated. Early one Wednesday morning in May, a fatal shooting took place in an East Orange apartment—an apparent drug assassination. Borgo had been working on the case since 4 am. The crime dashboard showed that except for the homicide, no crimes had been reported in the city through mid-morning. “It’s a good day in one sense,” Borgo says, “but you can’t have a good day when your one crime is the ugliest one of all. I’m not having a good day; I’m having a terrible day.” He tried to take heart from the overall statistics. The night shift was down 73 percent in crimes that week, compared with the same week last year; the day shift was down 81 percent. And over the last five months, the department was still down one murder from the previous year, even after that morning’s shooting. “We’re going to keep it going by being proactive, but this homicide is a major concern to me,” he agonizes.

Cordero is amazed that the most radical premise of Compstat policing—that the police can lower crime—is still not universally held among top managers. “When I hear from chiefs, ‘Crime results from the economy,’ my response is: ‘And you haven’t retired . . . why?’ ” As for Borgo, he keeps a large graph of the city’s historic crime drop on a wall in the police station to imbue his beat officers with the urgency of their mission. “People were being victimized at an unbelievable rate before,” he says. “If crime was still at 2003 levels, we’d have 14,000 more victims today.”

Other NYPD grads have also had a significant effect on their new cities through the application of Compstat principles, easily outstripping national crime averages. For example, Jane Perlov, a former NYPD deputy chief, brought violence in Raleigh, North Carolina, down 33 percent between 2001 and 2007 by breaking the city up into six police districts and making the district leaders responsible for crime on their watches. John Romero, an NYPD deputy inspector, lowered crime in Lawrence, Massachusetts, over 50 percent from 1999 to 2005 by demanding performance from his commanders and basing strategies on the most up-to-date, accurate information. Timoney, the first NYPD Compstat-era commander to take the reins of another department, reduced homicides in Philadelphia over 25 percent in two years—the first homicide decrease that violent city had seen in 15 years. And Bratton has slashed crime by 34 percent since becoming chief of the LAPD.

An NYPD hire can produce these effects because, as Cordero discovered, Compstat crime analysis and accountability are far from ubiquitous, despite their proven track record. “These were new principles to people here,” says Thomas Belfiore, who took over the Westchester County Department of Public Safety in 2003. “I asked for monthly reports; they were all verbiage. Very little was actually measured.”

Even if some version of Compstat has preceded an NYPD grad, it likely lacks the requisite oomph. “There was a Compstat here before,” observes Edmund Hartnett, the feisty chief of the Yonkers Police Department, “but—how to say this diplomatically?—it was city hall–driven; there was little interaction over strategies and tactics.” Hartnett has posted the funeral card of Compstat’s primary architect, the late Jack Maple, on his wall, so that “the Jackster” will always be watching over him. Maple would presumably be pleased that Hartnett brought crime to a ten-year low in Yonkers during his first year leading the department in 2007. “We weren’t getting crime updates before,” says Sergeant Mike Papaleo, head of Yonkers’s newly energized Street Crimes Unit, which targets guns and violent crime. It could take a couple of weeks for data to trickle down to the field. “Now, because of the information out of Compstat, I can assign my guys to immediately tackle patterns as they emerge.” Commanders like Papaleo also receive news of individual crimes on their BlackBerrys every three hours.

New York City is ringed to its north by Compstat graduates. Nearly all the major jurisdictions in Westchester County—Yonkers, White Plains, Mount Vernon, Rye, and the county itself—are now led by a crime-analysis disciple. In some quarters, this has produced—along with crime drops—an even greater level of the usual resentment against outsiders. One Westchester County chief asked another, who had been brought in from New York: “Why is the NYPD always getting these jobs? They should be our jobs.” Keeping NYPD memorabilia in one’s office to a minimum is advisable, the NYPD veteran suggests. Cordero studied management manuals to prepare himself for shaking up the East Orange force. He overcame the inevitable resistance to change “by quick victories and a vision of where we wanted to go,” he says. “It’s a huge challenge, telling a deputy chief with 30 years’ experience: ‘We’re doing things differently now.’ ”

NYPD recruits also have to be careful not to bring NYPD-scale demands to their new departments. After all, no other police department in the country has the resources available to New York commanders. “Your education in the NYPD is invaluable, but [it makes] you think that’s how the rest of the world is,” Westchester County chief Belfiore warns other new bosses. “You’re used to pressing a button and saying: ‘I need a communication unit that speaks Spanish to help me find a missing five-year-old.’ Get ready: you’ll have a girl on the emergency services team who lives in [remote] Dutchess County, and you’ll have to wait an hour for her to get dressed and show up. You really have to temper your impatience. You can beat them down and take the heart out of them.”

David Chong, the affable commissioner of the greatly overstretched Mount Vernon agency, outlines the triage decisions that commanders in less lavishly funded departments face: “In the NYPD, to move 20 to 30 officers in response to a problem is nothing; here, it’s an entire shift. If I want to do a weekend sweep to take back a corner, I have to pay half the force overtime to come in, and that means I’m taking from the budget of other city services. You have to learn that it’s a marathon, not a sprint.” Chong has compensated for thin staffing by pressing his detectives to get as much intelligence as they can from victims as well as their assailants, since in his jurisdiction, today’s robbery victim may well be tomorrow’s perpetrator. He lowered violent crime 18 percent in 2007, but he longs for more manpower: “I could drive crime completely down in the central city if I had the resources,” he says wistfully.

But perhaps the biggest challenge that an NYPD transplant faces is not local resentment or a drastically reduced force but rather the clout that police unions possess elsewhere. “In the NYPD, no one sees the union contract,” says Pat Harnett, a major player in the Compstat revolution who ran the Hartford Police Department from 2004 to 2006. “In smaller departments, it’s the first thing they’ll show you: ‘This is the contract; you can’t do anything outside it.’ ” Labor-management relations were Cordero’s biggest challenge in Newton. “It’s a different culture up there,” he reports. “If you say, ‘Officer, you need to get out of your car,’ you get back: ‘It’s not in my contract, we need additional pay for that.’ ” In strong civil service systems, officers, not their commanders, in essence decide in which posts they will serve, based on seniority. In small towns, too, the union chief may live next door to the mayor and talk to him every day about the unreasonable demands that the new chief is placing on the department.

Union recalcitrance has driven some New York stars away from new jobs. John Timoney left the Philadelphia department, where he had little ability to put his top picks into leadership positions, “fed up with banging my head against the wall” with the unions over officer discipline and personnel decisions, he says. Former NYPD intelligence commander Dan Oates left the Ann Arbor department, he reports, frustrated with the power of Michigan’s labor law to “crush positive change.”

And a Newark police union has mounted an audacious challenge to Garry McCarthy, Newark’s only hope for escaping its decades-long stranglehold of violence. McCarthy, a Maple protégé and battle-hardened street cop, served as the NYPD’s chief crime strategist from 1999 to 2006. Since taking over the civilian position of police director in Newark in late 2006, McCarthy has moved accountability for crime to his precinct commanders, required 150 officers to leave their desks to fight crime on the streets—including, most controversially, on nights and weekends—and beefed up the department’s analytic abilities. He has also uncovered gross mismanagement of the department’s overtime budget. For his labors, the union representing Newark’s sergeants, lieutenants, and captains is suing to strip him of his powers, alleging that he is encroaching on those of the uniformed police chief. McCarthy is undaunted: “These people are gnats to me,” he told the Newark Star-Ledger. “I’m here with a mission.” If he wins the suit, McCarthy is confident of his future success. Homicides were down 44 percent in the first half of 2008 compared with the previous year. “We’re only scratching the surface here in Newark,” he says. “Wait till we start getting complicated.”

The absence of a regressive union culture in Gotham may help explain why the caliber of NYPD top brass is so high. Its executives stand “head and shoulders above the competition,” one ex-NYPD leader observes, perhaps because they actually have the authority to lead and innovate. New York City should reward its police unions, Oates says, for their unacknowledged flexibility.

For all the adjustments that smaller departments require of their new chiefs, they do offer ambitious crime-fighters an unparalleled intimacy with the communities that they serve. This April, Mount Vernon commissioner Chong was popping across to City Hall to snag a reporter an impromptu meeting with the mayor when a large man in a dented SUV politely accosted him. The driver had recently opened a bakery on a commercial thoroughfare and had noticed people streaming into and out of a nearby store without buying anything. There had already been a drug bust at the store, but it looked as though the activity had started up again. “Now I’m scared for my wife, who sometimes works alone” at the bakery, the businessman told Chong. Chong promised to follow up on the matter; he has since visited the bakery twice on his ubiquitous bike. The drug investigation is ongoing, but the couple is satisfied with the department’s response. “Chong’s a great guy,” the baker, Michael, enthused. “He’s approachable and makes you feel like he’s paying attention.”

Michael is just the sort of asset that long-struggling Mount Vernon needs. Forward-looking and optimistic, he has decided to invest in the city in the hope that it will experience the same turnaround that he witnessed in the Bronx and White Plains on his bread routes. “I see more foot traffic and stores coming my way,” he says. Owners are trying to organize a business improvement district, despite the difficult economy. “Everyone’s taking pride in their buildings and fixing up storefronts. It’s just a matter of time before everything is built up.”

Chong and his NYPD peers are acutely aware of the value of entrepreneurs like Michael, and they know how crucial policing is to their success. “If I can remove the fear of crime from this area,” Chong asserts, “people will come, developers will come. If it can be done in Harlem and on 42nd Street, it can be done here.” The redevelopment of Yonkers’s leafy waterfront, a short water-taxi ride away from Wall Street, began before Ed Hartnett took over the police department, but its continuing viability rests on keeping crime down. And East Orange has added yet more proof to the assertion that Cordero made at his 2004 swearing-in: “It’s been proven, time and again, that safety is vital to the rebirth of great American cities.” Standing-room-only crowds engage in bidding wars at auctions of commercial and residential properties; the city’s stately old homes are getting long-overdue makeovers; and neighboring Orange, still mired in corruption and crime, looks on enviously at East Orange’s policing revolution.

Cordero, Hartnett, and other members of the NYPD diaspora have been hit with the usual racial-profiling charges as they try to rid their cities of criminals; Yonkers has even had a visit from Al Sharpton himself. The race-baiters are oblivious to the fact that the greatest beneficiaries of proactive policing are blacks, who make up the overwhelming share of urban crime victims. The sixties-era excuse for crime has it exactly backward: crime is not the result of a bad urban economy, but it will certainly contribute to one. When crime declines, not only are black lives saved, but urban economies can rebound and provide jobs to people with the drive to get ahead.

The anti-cop agitators may be indifferent to the toll of crime on the people they claim to care about, but the black mayors whom several members of the NYPD diaspora work for are not. “We make it no secret that public safety is paramount,” says Mount Vernon mayor Clinton Young. “As long as the kids are safe, and the elderly safe, we are doing our job.” And as long as Compstat policing, the motor of New York City’s unanticipated turnaround in the 1990s, continues to spread throughout the United States, more of America’s great cities can look forward to futures of safety—and of opportunity, wealth, and creativity.