Urban America began falling apart in the 1960s, with skyrocketing crime and worsening disorder. Vagrants and drug dealers colonized streets, parks, and other public spaces. Many once-vibrant city neighborhoods collapsed. The crisis had many causes, including the flight of industrial jobs from northern and midwestern cities. But profound changes in attitudes and government social policy played major roles, too. Crucial adjustments to welfare programs, spurred by liberal policymakers’ belief that the poor were victims of an unjust system, discouraged work and undermined families. The 1960s cultural revolution, which endorsed experimentation with drugs, brought more addiction—and more drug-fueled crime. And as the crisis intensified, policymakers lowered penalties for many crimes, seeing lawbreakers, too, as victims of society, so crime got worse still. Though such policies, championed nationally by President Lyndon B. Johnson and locally by mayors like New York’s John Lindsay, were well-intentioned, they helped produce an urban netherworld.

As City Journal readers know well, cities woke up from this nightmare in the 1990s, with smarter and more aggressive policing, tougher criminal sanctions, greater focus on quality-of-life concerns, welfare reform, and other policy changes. Crime plummeted in many cities, and many city economies surged. Some cities, including New York, became models of urban flourishing.

Yet, tragically—and bewilderingly, given such improvements—a new generation of progressive urban politicians seem intent on returning to some of the policies that cost cities so dearly decades ago. They’re pulling back on enforcement of quality-of-life infractions, ceding public space again to the homeless and drug users, undermining public school discipline, and releasing violent criminals back into communities or refusing to prosecute them in the first place. And lo and behold, crime is starting to rise, and the streets of otherwise successful cities like San Francisco, Seattle, and even parts of New York are filling up with human excrement, drug paraphernalia, and illness-wracked homeless encampments. Residents are growing fearful.

Today’s progressives don’t have the excuse of naiveté, as did their predecessors. In fact, arising as part of the resistance to President Donald Trump, they want to overturn the laws and values that support the nation’s bourgeois, strive-and-thrive culture. If their agenda makes middle-class Seattle homeowners, or businesspeople in San Francisco, or downtown merchants in Chicago uncomfortable—too bad.

Dramatic postwar changes in American life upended cities. Henry Ford’s affordable cars allowed families to move to newfangled suburbs, neither rural nor completely urban, and especially from the 1950s on, many made that choice. So, increasingly, did businesses, as interstate highways, displacing canals and ports, made shipping via truck from the cheaper suburbs easy. Cities hemorrhaged jobs—above all, blue-collar jobs—just as a generation of poor Southern blacks migrated to northern and midwestern urban neighborhoods, seeking opportunity. They were followed, after mid-1960s immigration reforms, by waves of poor, uneducated foreign workers. Many struggled to find the American dream, though the country was prospering. Worried about the entrenchment of a new urban poor, America’s political leaders launched the War on Poverty. The Johnson administration’s chief antipoverty warrior, Sargent Shriver, predicted that it could be won in just a decade.

Shriver and like-minded policymakers designed programs far more ambitious than those of the New Deal liberalism that had characterized the Democratic Party since Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s election in 1932. Though the New Deal vastly expanded the government safety net, it still recognized a connection between work and upward mobility and viewed government’s role as that of a temporary helper when someone was truly down and out. The officials behind the War on Poverty, by contrast, saw the poor as powerless, crushed by economic and cultural forces that could be overcome only with massive government help. Instead of temporary aid, welfare would now be a right, which the poor were entitled to receive, and benefits became far more generous, so that, by the late 1970s, welfare payments and other government aid now brought in about as much money as low-wage work.

Welfare use took off. In New York City, the rolls expanded from 500,000 to more than 1 million people, even as the city’s population was shrinking. Traditional family structure broke down at a rapid rate, with unwed mothers, mostly minorities, treating welfare as a long-term way of life and fatherless children becoming the norm in many inner-city neighborhoods. The removal of stigma for being on relief, together with 1960s-era cultural upheavals that encouraged greater sexual license, formed what City Journal contributing editor Fred Siegel called “dependent individualists,” who assumed that they had “a right to bear children and the state had the obligation to support them.” The result? “An extraordinary transfer of responsibility from the family to the state.” For liberal reformers, “the sharpest disappointment was the sudden upsurge in dependency,” Charles Morris wrote in his 1980 book, The Cost of Good Intentions. “The original strategists of antipoverty programs seemed sincerely to believe that the increased opportunities for minorities from Great Society programs and civil rights victories would actually reduce welfare rolls. Instead, something like the opposite happened.”

Metastasizing crime and disorder accompanied the rise in dependency, with much of the criminal activity associated with fatherless and poorly socialized young males. The nation’s violent-crime rate blasted from 161 crimes per 100,000 people in 1960 to 364 a decade later, reaching a terrifying summit of 758 in 1991. Overwhelmed police departments, some of which had seen their budgets cut in favor of social programs, struggled to cope. During the 1960s, the risk of a perpetrator getting apprehended for committing robbery declined threefold, according to Charles Murray’s calculations in Losing Ground, his 1984 critique of welfare policy and its social consequences.

“A stable neighborhood of families who care for their homes, mind each other’s children, and confidently frown on unwanted intruders can change, in a few years or even a few months, to an inhospitable and frightening jungle,” James Q. Wilson and George Kelling warned in “Broken Windows,” their seminal 1982 Atlantic article on the myriad factors contributing to urban breakdown. “A piece of property is abandoned, weeds grow up, a window is smashed. Adults stop scolding rowdy children; the children, emboldened, become more rowdy. Families move out, unattached adults move in. Teenagers gather in front of the corner store. The merchant asks them to move; they refuse. Fights occur. Litter accumulates. People start drinking in front of the grocery; in time, an inebriate slumps to the sidewalk and is allowed to sleep it off.”

Wilson and Kelling’s vivid essay became one of the turning points in the battle to conquer chaos. Slowly, public officials in a few cities stopped ignoring the small acts of disorder that cumulatively undermined neighborhoods. Police in New York started arresting fare-beaters in the subway, dispersing aggressive panhandlers, and sweeping drug dealers out of parks and streets—and discovered that the minor offenders were often wanted for graver crimes. Prosecutors, recognizing that a small percentage of lawbreakers accounted for much of an area’s crime, worked to keep repeat offenders off the streets. New kinds of neighborhood groups, including business-improvement districts, cleaned up parks and other public spaces, re-creating order. Welfare reform got a majority of recipients off the dole and back to work.

Crime began falling quickly in New York, and then elsewhere, as other cities took up the ideas. Since 1990, violent crime in Gotham is down by nearly 70 percent, with the murder rate down 80 percent. Nationwide, violent crime has fallen nearly 50 percent since the early 1990s, while crimes against property have dropped by 55 percent. The effects have been most visible in neighborhoods that had suffered the most. Brooklyn’s Bushwick, a former blue-collar neighborhood torn apart by social disorder, has watched its formerly battle-scarred landscape of vacant lots and empty buildings transform into a thriving community. The devastated South Bronx has been renamed SoBro, where residents fleeing Manhattan’s stratospheric prices have been snapping up townhouses and condos. Similar revivals have occurred in Los Angeles’s Highland Park neighborhood, Northern Liberties in Philadelphia, and Detroit’s midtown, among other formerly blighted areas.

Ironically, it is these very successes that have created the conditions for the current backsliding. The remarkable revival of neighborhoods in many cities, along with surging, tech-driven urban economies, has lured a new generation of educated young singles and well-to-do families to become city dwellers, and they’ve got the progressive beliefs typical of their demographic. The disorder of the 1960s, the drug wars of the 1970s, the brutal gang-murder sprees of the 1980s—these are little more than sensational headlines from a barely imaginable world for many of these new urbanites. And with this changing demographic has come a resurgence of progressive urban governance. After two decades of mayoral rule by a moderate Republican, Rudy Giuliani, and a centrist Democrat, Michael Bloomberg, New Yorkers in 2013, for example, elected Bill de Blasio, a leftist Democrat. Other successful cities, such as Seattle and Portland, which had escaped the worst disorders of the 1960s and now bustle with technology workers, similarly moved leftward, mirroring the elite progressivism of their workforces.

The influence of the new progressives is most evident in recent debates over policing. The shooting of Michael Brown by Ferguson, Missouri, officer Darren Wilson in August 2014 (later found by a grand jury to have been justified) ignited a national wave of recriminations about police use of force against black men. The narrative, picked up by progressive politicians and elite media outlets and amplified by the activism of the Black Lives Matter movement, claimed that proactive policing was a mortal threat to minorities—despite ample evidence that police use of force had plummeted over the years, including against minority suspects. Since 1991, the peak year of crime in New York City, to take the most striking example, the number of yearly shootings by the New York Police Department has declined by two-thirds—a testament to the force’s professionalism and to the impact that major crime declines have had on the need for cops to use their weapons.

Baltimore’s grim recent experience shows what can happen when the new narrative takes hold. In April 2015, Freddie Gray, an African-American in police custody for possession of an illegal knife, died a week after falling into a coma in the back of a police van. Following the incident, which set off extensive rioting in Baltimore’s minority neighborhoods, the city’s progressive leaders harshly criticized the police department, charging it with being abusive toward minorities. Though one Gray witness—a fellow prisoner—told investigators that the handcuffed suspect had been smashing his head against the side of the van as he was transported, local prosecutors indicted six of the officers involved. (Juries acquitted three of the cops, and prosecutors dropped charges against the rest.) Hostility to the police went right to the top of Baltimore’s political hierarchy. In December 2016, more than a year after Gray’s death, police brass gathered to discuss an alarming spike in carjackings, with new mayor Catherine Pugh in attendance. (Pugh resigned this past May.) After listening to the police officials discuss crime-fighting strategy, according to one account, she grew agitated, castigated the cops, and declared the meeting a waste of time. The police should seek to get minority kids (suspected of committing the carjackings) jobs or into after-school programs, she said, and then they wouldn’t need to steal cars—a perfect evocation of the once-discredited 1960s-era attitude.

Demoralized by the lack of political support—indeed, by the outright opposition of the mayor’s office—police abandoned proactive enforcement, and Baltimore descended into anarchy. In 2011, with the police fully engaged, murders in the city had fallen to 197—the first time in decades that Baltimore had seen fewer than 200 killings in a year. Since the Gray incident, Baltimore has had four straight years of 300-plus murders, and 90 percent of the victims were black. “In 2017, the church I attend started naming the victims of the violence at Sunday services and hanging a purple ribbon for each on a long cord outside,” wrote one columnist. “By year’s end, the ribbons crowded for space, like shirts on a tenement clothesline.”

Influential progressive groups have reinforced the anti-law-enforcement narrative, funding campaigns to soften criminal laws. In 2014, for instance, George Soros’s Open Society Policy Center and the American Civil Liberties Union, together with some technology millionaires, financed a successful California ballot initiative to reduce penalties for nonviolent property crimes, such as shoplifting, grand theft, fraud, and forgery, with the aim of ending “mass incarceration” in the state. If a theft amounted to less than $950 in value, Proposition 47 held, it would henceforth become a mere misdemeanor. Backers raised $10 million and outspent opponents, such as California police organizations, by 20 to one. Subsequent to Prop. 47’s passage, petty crime has predictably risen in California’s largest cities. Cops have seen a surge in organized “smash-and-grab” rings, which snatch purses and cameras from tourists and shatter car windows to steal any valuables inside—in San Francisco, car break-ins soared by 30 percent in 2015. Shoplifting gangs have made life hell for retailers in many California municipalities. “We’ve heard of cases where they’re going into stores with a calculator so they can make sure that what they steal is worth less than $950,” Robin Shakely, Sacramento County assistant chief deputy district attorney, told a local TV station. The lack of serious penalties for such “minor” offenses has reportedly made police less inclined to pursue the perpetrators.

New York is unlearning the past, too. When New York police began prosecuting low-level crimes, such as subway fare-beating, in the late 1980s, they found that many of the perpetrators were wanted for more serious crimes as well. But in 2017, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. announced that his office would stop prosecuting fare-beating and similar low-level offenses, so that his office could focus on “serious crime.” An epidemic of turnstile-jumping has predictably resulted. Twice as many people in New York now commit the offense as five years ago. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority is losing more than $200 million a year as a result of fare-beaters, intensifying the agency’s budget squeeze. And who knows how many hardened criminals have been among the cheaters?

Soros funding is also helping to elect progressive prosecutors, whose chief intent seems not to punish crime but instead to reshape the criminal-justice system to make it less punitive. In Philadelphia, Soros backing boosted criminal-defense and civil rights attorney Larry Krasner in his winning campaign for city district attorney. Though Philadelphia’s crime rate is nearly 50 percent higher than the national average, Krasner’s attorneys have stopped seeking bail conditions for many of the accused; lowered charges against accused murderers, so that they can avoid mandatory-minimum sentencing under Pennsylvania law; and pledged never to use the death penalty. He’s promised not merely to seek the easing of laws against quality-of-life crimes but also to push for reduced sentences for violent criminals. In one controversial case, a Philadelphia man who shot a store owner during a robbery faced attempted murder, aggravated assault, and robbery charges, but Krasner struck a plea deal for a sentence of between three and a half and ten years. Six months later, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, William McSwain, leveled federal charges against the shooter, rebuking Krasner. “Potential criminals on the streets of our city are not stupid. They pay attention to what is happening at the District Attorney’s Office,” McSwain explained. “They’ve become emboldened. They think they can literally get away with murder.”

Chicago annually records the most murders of any American city. But in 2016, after Chicago police released a video showing officer Jason Van Dyke firing 16 shots at Laquan McDonald, a teen suspected of breaking into trucks on the South Side, and killing the boy, the dominant story was that the cops were victimizing minority neighborhoods. (Van Dyke was convicted of second-degree murder.) Several months later, voters elected progressive Kim Foxx as Cook County prosecutor. Her campaign charged the criminal-justice system with bias because minorities made up a disproportionate share of arrests and prosecutions, a reality that she pledged to change. She refused to acknowledge that the city’s minorities committed a disproportionate share of Chicago’s crime, as based on victim identification—victims who themselves were mostly black and Hispanic.

Foxx garnered national attention by cutting a deal to end prosecution against Jussie Smollett, the TV actor accused—with considerable plausibility—of staging an attack on himself by white Trump supporters. But Foxx has shown leniency against even violent criminals, releasing them to commit more mayhem. Earlier this year, for instance, two men with long criminal records shot and killed an off-duty Chicago police officer. One, the suspected trigger man, was on probation after a 2017 home invasion; the other had 13 prior arrests. Similarly, two men arrested for live-streaming the beating of a 42-year-old man on Facebook in 2018 were on probation, despite more than 20 prior arrests between them. “As long as we fail . . . to hold repeat violent offenders accountable for their actions, we’re simply going to continue to have these discussions on Monday mornings, because it’s the same people who are pulling the trigger in some of these communities,” frustrated Chicago Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson told the press.

Chicago progressives want to deny the police resources. One item on the agenda of the city council’s rising leftist coalition is stopping construction of a $90 million police academy to train new officers, which one councilman called a “new shooting gallery for cops.” Small wonder that “the street no longer fears Chicago police,” a Chicago Tribune editorial board member observed. “The cops know they are alone.” Criminals, she noted, “are emboldened to challenge the police because the politicians and media will not stand up for the police and are only too happy for any excuse to jump on the police to gain political support.” Criminals had “no fear of going to jail.”

The intensifying war on cops in Chicago, even as crime rates remain elevated, recalls 1970s Detroit, where radical activist Coleman Young became mayor by campaigning against the city’s police force, and subsequently slashed their ranks by 20 percent. Those cuts led to the infamous Cobo Hall riot in August 1976, where undermanned police were unable to contain gang members, who rampaged violently among the audience during a rock concert and later spilled out into city streets, shaking down residents. Detroit became one of America’s most violent cities, and the mayhem has persisted into the twenty-first century.

The same rationale undergirding the war on cops—that they disproportionately target minorities—has also justified relaxing discipline standards in urban public schools around the country. The effort began when the Obama administration declared it a civil rights imperative to scrutinize minority public school students’ disproportionate suspension rates, on the assumption that they reflected racial bias. Though critics pointed out that black teens were acting out in class and being disruptive at higher rates, wary schools pulled back on disciplinary measures. That predictably brought a resurgence of school violence reminiscent of the 1970s and 1980s. In St. Paul, where a new, progressive school superintendent attacked disproportionate minority suspensions as an example of “white privilege,” assaults against teachers tripled. A highly regarded principal was fired because his school suspended too many minority students. The Seattle school district was another leader in the effort to rethink discipline. Over a three-year period, starting in 2013, suspensions at the district’s Highline High School fell by three-fourths, with students kept in school “even if they cursed at teachers, fought with peers or threw furniture,” according to the Seattle Times. By the 2015–16 school year, “outright chaos” ensued, the Times reported. The district witnessed a gang rape, several murders were attributed to its pupils, and nearly a third of the Highline High School teaching staff resigned.

The Trump administration rescinded the Obama discipline guidelines, but some cities have kept easing discipline policies, deeming them racist. New York City’s Department of Education has initiated a policy that tolerates smoking marijuana among older students, for instance, giving them a warning card instead of more serious punishment. Irate teachers gave one Queens high school principal a no-confidence vote after pot smoke began wafting through the hallways, and he reportedly told them: “Marijuana is going to be legal soon, so what can we do?” Students started openly smoking pot in the bathrooms, and thefts from locker rooms skyrocketed, as an atmosphere of lawlessness took hold. “Staffers blamed non-existent enforcement and a watered-down DOE discipline code, which discourages suspensions,” a New York Post report explained.

Washington Square’s Dark Zone

On a sunny weekend afternoon, Washington Square Park looks like a Jane Jacobs–Michael Bloomberg urbanist fantasy come true. Hundreds of people enjoy the public square in diverse ways. Sunbathers, musicians, chess players, lovers, acrobats, dogs, tourists, kids, and artists combine to fill ten acres of lower Manhattan in a harmonious collage of city life.

On the western edge of the park, though, a tree-shaded alley presents a scene more reminiscent of Panic in Needle Park or Last Exit to Brooklyn. Men holding up lampposts eye passersby and quietly solicit, “Smoke, smoke?” Hard-bitten homeless people with matted hair and filthy sweatshirts slump on benches, jumping up periodically to yell, pace around, and flop back down a minute later. Bent at the waist, an addict nods in the middle of the path. A group of men sit on a bench chatting, as one casually counts twists of crack cocaine from his palm into his baseball cap, in midafternoon.

Marijuana-dealing has been a feature of Washington Square Park for years. But the current scene differs qualitatively from the park’s traditional vibe. In his 2018 book The Taming of New York’s Washington Square, sociologist Erich Goode claims that selling pot is “routine” and contained—a minor, harmless feature of park life. “From time to time, the media or concerned citizens will attempt to generate a moral panic. . . . These panics flare up and die down.” Goode maintains that while “the sale of marijuana is routine and ongoing, its overt use is uncommon.”

I’m not sure when Goode last spent any significant time in Washington Square, but not only is the “overt use” of marijuana ubiquitous; the overt use of crack cocaine is becoming hard to miss. I spent a few hours the last couple of weekends sitting on benches near the center of the drug activity, just to observe. I have been walking through and around Washington Square and the East Village for 30 years, and I lived for more than a decade near a notorious drug corridor in upper Manhattan, so I’m no wide-eyed newcomer. What’s going on right now is bad news.

Walking into the northwest corner of the park at about 3 p.m., I overhear the tail end of a transaction: “Leave the money there,” an older Rasta man tells someone. The buyer stuffs a few tens into the slats of his bench. I pass a poker game and sit down on an empty bench across from a guy who is sound asleep. Sneakers, bags, litter, and blankets lie around in heaps; I see a pup tent erected in the ivy. Three or four men, in their forties or fifties, eye me curiously, and one comes over to ask if I want weed. I’m okay, I tell him. “What else you need, man?”

After about five minutes, a lanky redhead in a blue tank top comes marching past. He sits near the poker game and greets someone with an elaborate handshake, and then after half a minute steps away. He sits next to some friends, takes out a small glass tube, fiddles with it, lights up, and starts exhaling smoke. His associate, who looks as though he has been sleeping outside, takes the pipe but is more circumspect: he leans over the back of the bench to smoke.

A woman dozing next to them comes to life. Somewhere between 30 and 60, she wears a stringy wig. She stumbles between the benches, hollering imprecations, drinking from a pint bottle of vodka. A hardcore addict shuffles by in the other direction, holding his pants up with one hand. A few minutes later comes a youngish woman with horrible marks over her arms, legs, and face. I see her in the park regularly, usually crying matter-of-factly, as though weeping is just her natural tone. “I’m not a little girl, and you can’t tell me what to do, because I’m not a little girl,” she sniffles. She roots through the pockets of the sleeping man, but familiarly, as though he wouldn’t mind. He doesn’t wake up. Leaving, I pass the Rasta guy again, talking to a foreign tourist. He looks at me and asks, “Are you smoking?” with his hands raised in the universal “Or what?” gesture.

Coming back the next day, I see a clutch of ten or 15 people circulating like commodity traders. Money and goods change hands openly, without the disguise of complicated greetings. From about 30 feet away, someone sitting behind a table raises his hand at me and shouts, “Yo! Yo!” He puts his fingers to his lips to indicate smoking. The guy in the blue tank top is again hitting his crack pipe. Under a denim jacket, someone is either shooting up or doing something else he wants to hide. About 15 or 20 people appear intrinsic to the park drug trade, with another 15 or 20 hangers-on.

All this activity takes place a beer can’s throw from a playground and other, more salubrious, park recreations. People stroll past the passed-out addicts and watchful dealers without fear, though with the cautious sense that they’re passing through a restricted zone, where they wouldn’t stop to picnic or let their children play. I ask two cops who patrol the area what they think about the open-air drug market. “That’s why we walk through there,” says the NYPD sergeant, though their patrols pause drug sales for barely a minute.

Washington Square Park is a tolerant, open space, suited to all kinds of activity, and New Yorkers surely want to keep it that way. The city has come too far to allow its parks to become swamps of depravity.

—Seth Barron

Homeless populations in progressive cities like San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland have swelled as city officials have grown increasingly tolerant of people living on their streets, blaming it on economic injustice, not mental illness and drug abuse. “The explosion of the homelessness crisis is a symptom of how deeply dysfunctional capitalism is and also how much worse living standards have gotten with the last several decades,” one Seattle City Council member, a representative of the city’s Socialist Alternative party, contended. It’s another replay of an old story. Back in the 1970s, advocates had coined “homeless” as an alternative to words like “underclass,” typically used to describe people living on the streets. Some advocates admitted that ascribing the plight of street people to the failures of America’s economic system was a strategy to generate sympathy for them. As a former homeless-services administrator for New York City told the New York Times in 1992, “I had hewed to the party line that the solution to homelessness is housing. The belief was that if you focused on drug problems or family breakdown, you played into that blaming-the-victim mentality,” Nancy Wackstein said. “You didn’t want to say that people’s problems were a result of their own actions because then you would get no public support for helping them.”

Today, reviving that party line, Seattle politicians have permitted encampments of vagrants to proliferate in parks, empty lots, and other open spaces. Enforcement against drug use, petty crime, and acts of disorder like public urination has declined, producing an urban landscape increasingly littered with trash, human feces, and drug paraphernalia—in one of America’s most prosperous cities. Rather than a strategy of enforcement and intervention that attempts to get the homeless off the streets and get them the help they need, the city’s acceptance of street living has “left sick tortured souls to wander the streets,” a reporter for a local TV station said earlier this year.

To Seattle’s politicos, what’s needed to ease the problem is more money. Yet the city already spends hundreds of millions yearly on homelessness—just not enough of it on the kind of interventions that might help. Its council passed an employer tax in 2018 meant to raise some $120 million more per year for homeless services but had to rescind it when companies and residents revolted. At one community meeting, a resident castigated public officials for ignoring the truth. “Can we talk about the elephant in the room?” the resident asked, to applause from the crowd. “This is a drug problem. I’ve only heard it be called a housing problem.” Even the homeless themselves, when interviewed, admit that virtually all the city’s street people are drug users. In a city where police are constrained from battling the illegal drug trade by tolerant laws and lackluster prosecution, public policy is enabling a homeless drug culture. “It is impossible to combat the open-air drug market in Seattle,” one officer told TV station KOMO.

Seattle police polled by a local TV station placed the blame clearly on a political culture that had told them to stop enforcing various quality-of-life laws, as an expression of the city’s compassion. “People come here because it’s Free-attle,” one cop said. “They believe if they come here they will get free food, free medical treatment, free mental health treatment, a free tent, free clothes, and will be free of prosecution for just about anything, and they are right.” The statistics bear it out. For every 100 reports that police send to prosecutors requesting criminal charges against perpetrators, 46 never get filed. Most of those who do get charged ultimately see their charges dismissed. Only 18 of every 100 cases bring a conviction. And convicted criminals are frequently sent back to the streets, soon to commit crimes again. And even though the city’s mayor says that it’s wrong to equate rising crime in the city with increased homelessness, the data are clear. One analysis of the city’s top 100 repeat offenders found that many were homeless. One homeless musician who migrated to Seattle from Reno, Nevada, told KOMO that he uses methamphetamines daily. He’s been arrested 34 times since moving to Seattle four years ago, including for assault, attempted rape, and trespassing, but remains free.

The story in Portland and San Francisco is similar. Portland officials have sanctioned homeless encampments and made some of them “drug-friendly.” Residents in the city of some 650,000 call the police four times an hour to complain about the homeless. But the city’s political establishment, which regularly tolerates the civil disobedience of radical groups like Antifa, has defanged the police, even branding them as right-wing extremists and accusing them of over-policing. As in Chicago, Portland cops have pulled back, unleashing an epidemic of petty crime by street people. Writing in a local newspaper, the CEO of Columbia Sportswear, which has operations downtown, decried the disorder: “A few days ago, one of our employees had to run into traffic when a stranger outside our office followed her and threatened to kill her. On other occasions our employees have arrived at work only to be menaced by individuals camping in the doorway,” Tim Boyle wrote. “Given these experiences, it is a relief when the only thing we are dealing with is the garbage and human waste by our front door.” Reflecting the antipolice attitude that’s become typical, a local minister and homeless advocate wrote back, castigating Boyle for his call for more policing. “It’s our friends, neighbors and fellow Portlanders living on the streets whose safety is in greater jeopardy,” he maintained, referring to a police shooting of a homeless man brandishing a knife.

“Last year, San Francisco police fielded more than 28,000 complaints of human excrement in the streets.”

A decade ago, San Francisco was making headway against widespread vagrancy, passing laws that banned aggressive panhandling and lying on sidewalks. But lawyers from many of the city’s top firms, working pro bono to represent homeless people, fought every arrest and citation, discouraging the police. California’s state constitution also thwarted a campaign in the state’s cities, including San Francisco, to set up community courts like those that New York City established in the 1990s, where ticketed panhandlers were brought before judges immediately and often required to begin serving sentences for community service the same day that they were charged. As those efforts stalled in San Francisco, the city’s political establishment turned increasingly tolerant. By 2015, though residents had registered more than 60,000 complaints with the police over vagrancy, public urination, and other crimes associated with street people, cops arrested just 125 people on such charges. The city budget already expends $280 million on homeless services, but last November, voters approved a $250 million gross-receipts tax on city companies to pay for additional homeless services, including more shelters and hygiene programs. Critics had opposed the tax in part because in the last several years, San Francisco had already nearly doubled its homeless spending, with no appreciable effect. “What we can tell from past experience is that five years from now you’re still going to have 7,000 people out on the street,” Jim Lazarus of the city’s Chamber of Commerce said. Last year, police fielded more than 28,000 complaints of human excrement in the streets. One infectious-disease expert told a local TV station that the level of contamination on San Francisco’s streets was greater than in poor cities in Brazil, India, and Kenya. The homeless are also thought to be a key factor in the city’s rising crime. San Francisco now has the highest property-crime rate of any major city in America.

None of this is surprising. In their Atlantic article, Wilson and Kelling noted that the “unchecked panhandler is, in effect, the first broken window.” New York demonstrated the truth of that observation when, in the early 1990s, the city cracked down on the “squeegee men,” panhandlers who had long harassed motorists in the city by “washing” their car windows for donations. Then the city attacked open drug use in parks and on street corners. Change happened not from the top down against the most violent criminals, but from the bottom up, beginning with the establishment of day-to-day order. While incarceration rates rose at first in New York, as crime declined so did the city’s prison population, from about 17,500 in 1998 to about 8,000 today. That’s the effect of establishing and sustaining order. New York’s heavily minority communities saw the largest declines in crime, with thousands of lives saved.

The breakdown in public order in some progressive cities is not yet as widespread as it became 50 years ago. But the attitudes and policies that have brought on these troubles are spreading locally and nationally, a stark example of forgetting the lessons of the past. We shouldn’t condemn a new generation to relearning those lessons.

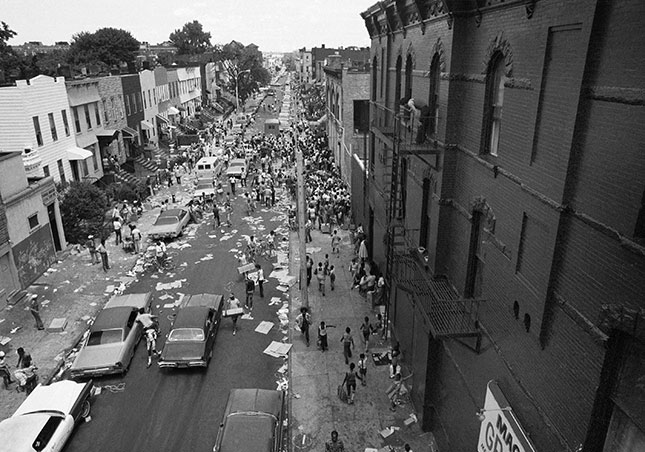

Top Photo: Social unrest in Baltimore in the wake of Freddie Gray’s 2015 death prompted police to reduce enforcement against lawbreaking. (JERRY JACKSON/BALTIMORE SUN/TNS/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)