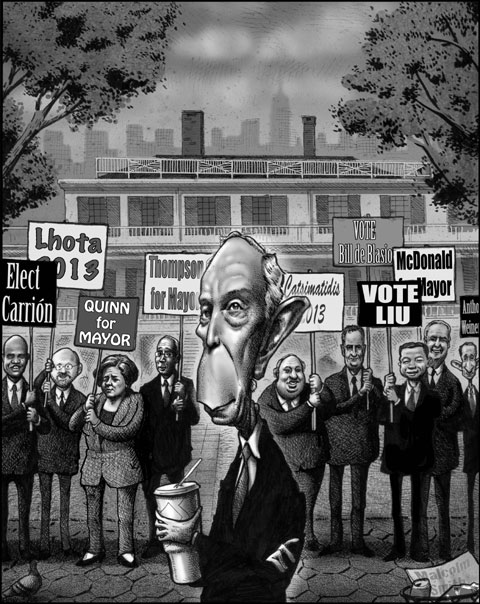

Listening to some of the candidates to succeed Mayor Michael Bloomberg, you’d think that New York City’s biggest challenge was how to spend billions of dollars in spare revenue. Bill Thompson wants to put 2,000 extra cops on the street at a cost of $200 million a year. One of his rivals, Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, pledges to introduce universal pre-K in the city’s schools, a project with a $530 million annual price tag. Thompson, de Blasio, and another candidate, New York City comptroller John Liu, want to build at least 60,000 units of new subsidized housing over the next four years. The bill for that could dwarf the cost of the police and school proposals.

But no matter how big the spending dreams of the city’s would-be mayors, one of them is going to wake up to a fiscal nightmare in November. New York’s budget has grown hugely over Mayor Bloomberg’s 12 years in office, and it may finally have outstripped the Wall Street–generated tax revenues that have made such profligacy possible. The next mayor won’t have the luxury of expanding the government; instead, he’ll have to figure out how to pay for one that’s already dangerously bloated.

If Bloomberg’s goal was soaking up revenue and leaving his successor as little to spend as possible, he seems to have pulled it off. Spending from city revenues rose from $28.9 billion when Bloomberg took office to $47.5 billion in fiscal year 2012 and will be an estimated $50.2 billion in 2013—a staggering 70 percent increase per resident. Inflation rose only 29 percent over the same period. Had Bloomberg held Gotham’s budget increase to the growth rates of inflation and population, the city would currently be spending $12 billion less a year.

Little of the new spending has funded more services for New Yorkers. What has swallowed the money is rising compensation, and especially benefits, for government employees. The annual price of financing workers’ pensions grew from $1.8 billion in Bloomberg’s inaugural budget to $8 billion in 2012. The tab for workers’ health care more than doubled, from $2 billion a year to $4.8 billion. Retirees add another $1.6 billion. The city now collects substantially more money than it did when Bloomberg took office, but increases in benefits, particularly health care and pensions, eat up half of that additional revenue.

The mayor has also expanded New York’s debt load enormously, adding to the budget pressure. According to the Citizens Budget Commission, total city debt hit $105 billion last year—almost double what it was when Bloomberg entered City Hall—in large part because of his aggressive capital-building program, announced in 2005, which anticipates borrowing $60 billion over a decade for various projects, including subsidized housing. As a result, the budget allocation for annual interest payments on debt jumped from $3.9 billion in 2002 to $5.8 billion in 2012, according to New York City’s Independent Budget Office. The Citizens Budget Commission expects that bill to rise by as much as 8 percent annually for the foreseeable future, reaching $7.5 billion in three years and commanding an ever-larger chunk of any new tax revenue.

At first, New York’s budget could absorb these spending increases, thanks to Wall Street’s power to generate tax revenue. In the fiscal year that ended in June 2005, for instance, Bloomberg hiked spending by 10 percent, but tax collections, fed by the Wall Street bubble, increased by an astonishing 13.4 percent, producing a surplus. Two years later, Bloomberg boosted spending by another 7.2 percent, but Wall Street–inflated tax revenues rose by more than 11 percent. Even after the market meltdown in 2008, federal policies to strengthen and bail out financial firms lifted Wall Street profits temporarily and provided enough growth in tax collections to give the mayor some fiscal wiggle room. More recently, as growth in tax revenues slowed, Bloomberg closed small budget deficits with a series of fiscal gimmicks, including selling new taxi medallions to raise money (a one-time maneuver) and shifting cash to the city’s general fund from a trust fund designed to pay future retirees’ health-care costs.

The mayor, contending that he had no choice but to spend away the city’s surging tax revenues, points to rising costs that were supposedly “uncontrollable”—a term that occurs frequently in Bloomberg-era budget documents. Some of those costs, however, were uncontrollable only because Bloomberg didn’t control them. A good example is fringe benefits, which the mayor considers uncontrollable because they’re negotiated in city contracts and must be honored throughout the duration of those contracts. But Bloomberg has negotiated many contracts during his 12 years as mayor, and in none of them has he achieved substantial savings in benefits. Similarly, the mayor deems debt service uncontrollable: once the government issues debt, he says, it must adhere to a repayment schedule. True—but it was Bloomberg who drove the government to issue so much debt in the first place. The next mayor may legitimately complain that he isn’t responsible for the debt problem; it’s disingenuous for Bloomberg to say the same.

The good news is that New York could start shrinking its swollen budget without cutting deeply into services. The bad news, at least from a political perspective, is that the city would have to rein in its worker-compensation costs. The public-employee unions have allowed their current contracts to expire without negotiating new ones, which means that the next mayor can pursue new deals and realize immediate savings. But wringing those savings out of the unions will require a hard-nosed negotiator—not a role that the mayoral candidates have embraced so far.

Still, the opportunity is there. The biggest savings would be in health care. The health plan for New York’s workers is one of the best and most expensive in the country for employees of major cities, and nine out of ten New York workers don’t have to contribute a dime toward their premiums. Further, the city pays the full cost of health care for retirees and their families, buying insurance for those who retire too early for Medicare and, for those on Medicare, paying their Part B premiums, which cover doctor services. The cost of retirees’ health care has ballooned by nearly 50 percent over the last six years.

The city’s health-care contributions are wildly generous compared with what other employers cover. In the private sector, employees for large corporations typically pay 20 percent to 23 percent of their premium costs, the Citizens Budget Commission has found. As for city workers, those in cities like Boston, Houston, and Phoenix contribute between 20 percent and 27.5 percent of their premiums, and New York State employees cover 16 percent or 31 percent of the cost, depending on whether they have individual health insurance or a family plan. Most municipal governments also require their retired employees to contribute to health premiums; for instance, Chicago pays for half, at most, of its retirees’ premiums, depending on how many years they have worked for the city. Even that partial subsidy is unaffordable, according to a recent study commissioned by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who has now decided to require Chicago retirees to seek subsidized health insurance on the state insurance exchange being created under the federal Affordable Care Act.

The Bloomberg administration has proposed to unions that the city seek competitive bids to replace its current provider of health-care benefits to workers, a move that the administration says could save the city hundreds of millions of dollars. Other observers have noted that requiring greater contributions from workers would yield even greater advantages. The Independent Budget Office estimates that if city workers contributed just 10 percent of their premiums, and if city retirees on Medicare paid for 50 percent of their Part B premiums (which would amount to about $1,000 a year), New York could save $650 million in 2014. If New York instead required its employees with family coverage to pay for 25 percent of their premiums and asked retirees too young for Medicare to pay half their premiums, as Chicago does, the annual savings would rise to $1.8 billion.

Taxpayers would support such an approach. In a recent Zogby poll commissioned by the Manhattan Institute, 60 percent of those surveyed said that city workers should contribute to their health-insurance premiums at a typical private-sector rate. Only 28 percent disagreed.

The next mayor may not be able to do much about the city’s skyrocketing pension costs, since the state, not the city, controls them. But he can certainly try to pay for employee benefits by negotiating productivity savings with unions, as fiscal experts have been urging Bloomberg to do throughout his tenure. These savings could include lengthening the municipal workweek from 35 hours to 40, eliminating so-called wash-up time in the police department and converting those minutes into actual tour duty, and getting rid of anachronistic incentive pay for sanitation workers on two-person trucks (a holdover from 30 years ago, when the city shifted from three-person to two-person teams). If a new mayor achieved just those three changes in his first year in office, the savings by fiscal year 2015 could amount to $750 million annually.

Skeptics might claim that such savings are doomed in advance by New York City’s restrictive collective bargaining rules, which require the mayor to negotiate changes with the unions. But a tough negotiator could present the unions with other, less palatable, cost-saving options if they resisted reform. When Mayor Rudy Giuliani took office in 1994, he confronted a sanitation union that refused to yield on staffing changes, even though recycling had cut the workload so sharply that many garbage collectors were putting in half-days. So Giuliani threatened to privatize some city sanitation routes—and the union finally compromised, returning its members to full-day work schedules and saving the city hundreds of millions of dollars. Bloomberg, by contrast, refused even to consider privatizing city services, a decision that sacrificed key leverage over truculent unions. No wonder he proved unable to cement meaningful contract savings.

New York’s next mayor will also have to bring the city’s debt under control. In 2009, after fiscal experts began warning that the city’s indebtedness was becoming unsustainable, Bloomberg announced that he would trim borrowing in the second half of the ten- year capital plan. But debt has kept rising— by $4 billion in fiscal year 2011 and another $4 billion in fiscal year 2012. The next mayor should table some currently planned programs that require more debt, such as $1 billion for subsidized housing and another $1 billion for economic development projects.

Absent a new economic boom, which few economists see on the near horizon, the next mayor won’t be able to balance the city’s budget without some cost-cutting moves along these lines—unless, that is, he wants to raise taxes substantially. One candidate, de Blasio, has already proposed a half-billion-dollar tax hike on the wealthy, and other Democratic candidates have hinted that they’d increase taxes, too.

New York, though, is already by far America’s most heavily taxed big city (see “Overburdened”). According to the Independent Budget Office, Gotham takes about 75 percent more, on average, in taxes on wages and profits than major cities like Atlanta, Chicago, and Los Angeles, none of which is a particularly low-tax locale. And any city tax increase would add to recent hikes at both the federal level (in payroll and income taxes) and the state level (including a surcharge on wealthy New Yorkers enacted in 2011). For an affluent New York City resident, the top state-plus-city tax rate is already nearly 13 percent. Raising that rate even higher would make the city less competitive for investment by individuals and companies at a time when business investment is already sluggish. And new capital is exactly what New York needs, since Wall Street, which for years seemed immune to the city’s high tax rate, is now shrinking.

Aside from occasional hints about tax hikes, the mayoral contenders have avoided talking about the city’s impending budget crisis. That shirking could lure voters into a false complacency—an echo of their attitude in the 1989 mayoral campaign, when the public and the press mostly ignored the imminent budget crunch that a Wall Street downturn was bringing. When the winner of that race, David Dinkins, took office in early 1990, he encountered an immediate fiscal emergency and had no plan for dealing with it. Indeed, he worsened the problem, awarding a big pay increase to city teachers, who had backed his campaign. Four years of fiscal crises followed.

The candidates should talk frankly about the city’s budget problems. And with the Democratic candidates likely to counter those problems with tax hikes, it’s up to the Republicans to articulate a no-new-taxes solution. That means restraining the rapid growth of city spending, especially on personnel—a strategy that the city must embrace if it hopes to prosper.

What to Do

- Require city employees and retirees to contribute to their health-care premiums, saving the city $650 million to $1.8 billion annually.

- Reduce debt issuance, which has nearly doubled under Bloomberg, to slow the growth in debt service in the city’s budget.

- Lengthen city employees’ workweek, which is currently 35 hours for many workers, by several hours to achieve cost savings.