It’s a lonely job, working the phones at a college rape crisis center. Day after day, you wait for the casualties to show up from the alleged campus rape epidemic—but no one calls. Could this mean that the crisis is overblown? No: it means, according to the campus sexual-assault industry, that the abuse of coeds is worse than anyone had ever imagined. It means that consultants and counselors need more funding to persuade student rape victims to break the silence of their suffering.

The campus rape movement highlights the current condition of radical feminism, from its self-indulgent bathos to its embrace of ever more vulnerable female victimhood. But the movement is an even more important barometer of academia itself. In a delicious historical irony, the baby boomers who dismantled the university’s intellectual architecture in favor of unbridled sex and protest have now bureaucratized both. While women’s studies professors bang pots and blow whistles at antirape rallies, in the dorm next door, freshman counselors and deans pass out tips for better orgasms and the use of sex toys. The academic bureaucracy is roomy enough to sponsor both the dour antimale feminism of the college rape movement and the promiscuous hookup culture of student life. The only thing that doesn’t fit into the university’s new commitments is serious scholarly purpose.

The campus rape industry’s central tenet is that one-quarter of all college girls will be raped or be the targets of attempted rape by the end of their college years (completed rapes outnumbering attempted rapes by a ratio of about three to two). The girls’ assailants are not terrifying strangers grabbing them in dark alleys but the guys sitting next to them in class or at the cafeteria.

This claim, first published in Ms. magazine in 1987, took the universities by storm. By the early 1990s, campus rape centers and 24-hour hotlines were opening across the country, aided by tens of millions of dollars of federal funding. Victimhood rituals sprang up: first the Take Back the Night rallies, in which alleged rape victims reveal their stories to gathered crowds of candle-holding supporters; then the Clothesline Project, in which T-shirts made by self-proclaimed rape survivors are strung on campus, while recorded sounds of gongs and drums mark minute-by-minute casualties of the “rape culture.” A special rhetoric emerged: victims’ family and friends were “co-survivors”; “survivors” existed in a larger “community of survivors.”

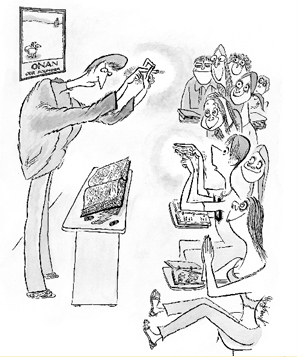

An army of salesmen took to the road, selling advice to administrators on how to structure sexual-assault procedures, and lecturing freshmen on the “undetected rapists” in their midst. Rape bureaucrats exchanged notes at such gatherings as the Inter Ivy Sexual Assault Conferences and the New England College Sexual Assault Network. Organizations like One in Four and Men Can Stop Rape tried to persuade college boys to redefine their masculinity away from the “rape culture.” The college rape infrastructure shows no signs of a slowdown. In 2006, for example, Yale created a new Sexual Harassment and Assault Resources and Education Center, despite numerous resources for rape victims already on campus.

If the one-in-four statistic is correct—it is sometimes modified to “one-in-five to one-in-four”—campus rape represents a crime wave of unprecedented proportions. No crime, much less one as serious as rape, has a victimization rate remotely approaching 20 or 25 percent, even over many years. The 2006 violent crime rate in Detroit, one of the most violent cities in America, was 2,400 murders, rapes, robberies, and aggravated assaults per 100,000 inhabitants—a rate of 2.4 percent. The one-in-four statistic would mean that every year, millions of young women graduate who have suffered the most terrifying assault, short of murder, that a woman can experience. Such a crime wave would require nothing less than a state of emergency—Take Back the Night rallies and 24-hour hotlines would hardly be adequate to counter this tsunami of sexual violence. Admissions policies letting in tens of thousands of vicious criminals would require a complete revision, perhaps banning boys entirely. The nation’s nearly 10 million female undergrads would need to take the most stringent safety precautions. Certainly, they would have to alter their sexual behavior radically to avoid falling prey to the rape epidemic.

None of this crisis response occurs, of course—because the crisis doesn’t exist. During the 1980s, feminist researchers committed to the rape-culture theory had discovered that asking women directly if they had been raped yielded disappointing results—very few women said that they had been. So Ms. commissioned University of Arizona public health professor Mary Koss to develop a different way of measuring the prevalence of rape. Rather than asking female students about rape per se, Koss asked them if they had experienced actions that she then classified as rape. Koss’s method produced the 25 percent rate, which Ms. then published.

Koss’s study had serious flaws. Her survey instrument was highly ambiguous, as University of California at Berkeley social-welfare professor Neil Gilbert has pointed out. But the most powerful refutation of Koss’s research came from her own subjects: 73 percent of the women whom she characterized as rape victims said that they hadn’t been raped. Further—though it is inconceivable that a raped woman would voluntarily have sex again with the fiend who attacked her—42 percent of Koss’s supposed victims had intercourse again with their alleged assailants.

All subsequent feminist rape studies have resulted in this discrepancy between the researchers’ conclusions and the subjects’ own views. A survey of sorority girls at the University of Virginia found that only 23 percent of the subjects whom the survey characterized as rape victims felt that they had been raped—a result that the university’s director of Sexual and Domestic Violence Services calls “discouraging.” Equally damning was a 2000 campus rape study conducted under the aegis of the Department of Justice. Sixty-five percent of what the feminist researchers called “completed rape” victims and three-quarters of “attempted rape” victims said that they did not think that their experiences were “serious enough to report.” The “victims” in the study, moreover, “generally did not state that their victimization resulted in physical or emotional injuries,” report the researchers.

Just as a reality check, consider an actual student-related rape: in 2006, Labrente Robinson and Jacoby Robinson broke into the Philadelphia home of a Temple University student and a Temple graduate, and anally, vaginally, and orally penetrated the women, including with a gun. The chance that the victims would not consider this event “serious enough to report,” or physically and emotionally injurious, is exactly nil. In short, believing in the campus rape epidemic depends on ignoring women’s own interpretations of their experiences—supposedly the most grievous sin in the feminist political code.

None of the obvious weaknesses in the research has had the slightest drag on the campus rape movement, because the movement is political, not empirical. In a rape culture, which “condones physical and emotional terrorism against women as a norm,” sexual assault will wind up underreported, argued the director of Yale’s Sexual Harassment and Assault Resources and Education Center in a March 2007 newsletter. You don’t need evidence for the rape culture; you simply know that it exists. But if you do need evidence, the underreporting of rape is the best proof there is.

Campus rape researchers may feel that they know better than female students themselves about the students’ sexual experiences, but the students are voting with their feet and staying away in droves from the massive rape apparatus built up since the Ms. article. Referring to rape hotlines, rape consultant Brett Sokolow laments: “The problem is, on so many of our campuses, very few people ever call. And mostly, we’ve resigned ourselves to the under-utilization of these resources.”

Federal law requires colleges to publish reported crimes affecting their students. The numbers of reported sexual assaults—the law does not require their confirmation—usually run under half a dozen a year on private campuses and maybe two to three times that at large public universities. You might think that having so few reports of sexual assault a year would be a point of pride; in fact, it’s a source of gall for students and administrators alike. Yale’s associate general counsel and vice president were clearly on the defensive when asked by the Yale alumni magazine in 2004 about Harvard’s higher numbers of reported assaults; the reporter might as well have been needling them about a Harvard-Yale football rout. “Harvard must have double-counted or included incidents not required by federal law,” groused the officials. The University of Virginia does not publish the number of its sexual-assault hearings because it is so low. “We’re reticent to publicize it when we have such a small ‘n’ number,” says Nicole Eramu, Virginia’s associate dean of students.

Campuses do everything they can to get their numbers of reported and adjudicated sexual assaults up—adding new categories of lesser offenses, lowering the burden of proof, and devising hearing procedures that will elicit more assault charges. At Yale, it is the accuser who decides whether the accused may confront her—a sacrifice of one of the great Anglo-Saxon truth-finding procedures. “You don’t want them to not come to the board and report, do you?” asks physics professor Peter Parker, convener of the university’s Sexual Harassment Grievance Board.

The scarcity of reported sexual assaults means that the women who do report them must be treated like rare treasures. New York University’s Wellness Exchange counsels people to “believe unconditionally” in sexual-assault charges because “only 2 percent of reported rapes are false reports” (a ubiquitous claim that dates from radical feminist Susan Brownmiller’s 1975 tract Against Our Will). As Stuart Taylor and K. C. Johnson point out in their book Until Proven Innocent, however, the rate of false reports is at least 9 percent and probably closer to 50 percent. Just how powerful is the “believe unconditionally” credo? David Lisak, a University of Massachusetts psychology professor who lectures constantly on the antirape college circuit, acknowledged to a hall of Rutgers students this November that the “Duke case,” in which a black stripper falsely accused three white Duke lacrosse players of rape in 2006, “has raised the issue of false allegations.” But Lisak didn’t want to talk about the Duke case, he said. “I don’t know what happened at Duke. No one knows.” Actually, we do know what happened at Duke: the prosecutor ignored clearly exculpatory evidence and alibis that cleared the defendants, and was later disbarred for his misconduct. But to the campus rape industry, a lying plaintiff remains a victim of the patriarchy, and the accused remain forever under suspicion.

So what reality does lie behind the campus rape industry? A booze-fueled hookup culture of one-night, or sometimes just partial-night, stands. Students in the sixties demanded that college administrators stop setting rules for fraternization. “We’re adults,” the students shouted. “We can manage our own lives. If we want to have members of the opposite sex in our rooms at any hour of the day or night, that’s our right.” The colleges meekly complied and opened a Pandora’s box of boorish, sluttish behavior that gets cruder each year. Do the boys, riding the testosterone wave, act thuggishly toward the girls? You bet! Do the girls try to match their insensitivity? Indisputably.

College girls drink themselves into near or actual oblivion before and during parties. That drinking is often goal-oriented, suggests University of Virginia graduate Karin Agness: it frees the drinker from responsibility and “provides an excuse for engaging in behavior that she ordinarily wouldn’t.” A Columbia University security official marvels at the scene at homecomings: “The women are shit-faced, saying, ‘Let’s get as drunk as we can,’ while the men are hovering over them.” As anticipated, the night can include a meaningless sexual encounter with a guy whom the girl may not even know. This less-than-romantic denouement produces the “roll and scream: you roll over the next morning so horrified at what you find next to you that you scream,” a Duke coed reports in Laura Sessions Stepp’s recent book Unhooked. To the extent that they’re remembered at all, these are the couplings that are occasionally transformed into “rape”—though far less often than the campus rape industry wishes.

The magazine Saturday Night: Untold Stories of Sexual Assault at Harvard, produced by Harvard’s Office of Sexual Assault Prevention and Response, provides a first-person account of such a coupling:

What can I tell you about being raped? Very little. I remember drinking with some girlfriends and then heading to a party in the house that some seniors were throwing. I’m told that I walked in and within 5 minutes was making out with one of the guys who lived there, who I’d talked to some in the dining hall but never really hung out with. I may have initiated it. I don’t remember arriving at the party; I dimly remember waking up at some point in the early morning in this guy’s room. I remember him walking me back to my room. I couldn’t have made it alone; I still had too much alcohol in my system to even stand up straight. I made myself vulnerable and even now it’s hard to think that someone here who I have talked and laughed with could be cold-hearted enough to take advantage of that vulnerability. I’d rather, sometimes, take half the blame than believe that a profound evil can exist in mankind. But it’s easy for me to say, that, of the two of us, I’m the only one who still has nightmares, found myself panicking and detaching during sex for many months afterwards, and spent more time looking into the abyss than any one person should.

The inequalities of the consequences of the night, the actions taken unintentionally or not, have changed the course of only one of our lives, irrevocably and profoundly.

Now perhaps the male willfully exploited the narrator’s self-inflicted incapacitation; if so, he deserves censure for taking advantage of a female in distress. But to hold the narrator completely without responsibility requires stripping women of volition and moral agency. Though the Harvard victim does not remember her actions, it’s highly unlikely that she passed out upon arriving at the party and was dragged away like roadkill while other students looked on. Rather, she probably participated voluntarily in the usual prelude to intercourse, and probably even in intercourse itself, however woozily.

Even if the Harvard victim’s drunkenness cancels any responsibility that she might share for the interaction’s finale, is she equally without responsibility for all of her behavior up to that point, including getting so drunk that she can’t remember anything? Campus rape ideology holds that inebriation strips women of responsibility for their actions but preserves male responsibility not only for their own actions but for their partners’ as well. Thus do men again become the guardians of female well-being.

As for the story’s maudlin melodrama, perhaps the narrator’s life really has been “irrevocably” changed, for which one sympathizes. One can’t help observing, however, that the effect of this “profound evil” on at least her sex life appears to have been minimal—she “detached” during sex for “many months afterwards,” but sex she most certainly had. Real rape victims, however, can fear physical intimacy for years, along with suffering a host of other terrors. We don’t know if the narrator’s “look into the abyss” led her to reconsider getting plastered before parties and initiating sexual contact with casual acquaintances. But if a Harvard student doesn’t understand that getting very drunk and becoming physically involved with a boy at a hookup party carries a serious probability of intercourse, she’s at the wrong university, if she should be at college at all.

A large number of complicating factors make the Saturday Night story a far more problematic case than the term “rape” usually implies. Unlike the campus rape industry, most students are well aware of those complicating factors, which is why there are so few rape charges brought for college sex. But if the rape industrialists are so sure that foreseeable and seemingly cooperative drunken sex amounts to rape, there are some obvious steps that they could take to prevent it. Above all, they could persuade girls not to put themselves into situations whose likely outcome is intercourse. Specifically: don’t get drunk, don’t get into bed with a guy, and don’t take off your clothes or allow them to be removed. Once you’re in that situation, the rape activists could say, it’s going to be hard to halt the proceedings, for lots of complex emotional reasons. Were this advice heeded, the campus “rape” epidemic would be wiped out overnight.

But suggest to a rape bureaucrat that female students should behave with greater sexual restraint as a preventive measure, and you might as well be saying that the girls should enter a convent or don the burka. “I am uncomfortable with the idea,” e-mailed Hillary Wing-Richards, the associate director of the Office of Sexual Assault Prevention and Women’s Resource Center at James Madison University in Virginia. “This indicates that if [female students] are raped it could be their fault—it is never their fault—and how one dresses does not invite rape or violence. . . . I would never allow my staff or myself to send the message it is the victim’s fault due to their dress or lack of restraint in any way.” Putting on a tight tank top doesn’t, of course, lead to what the bureaucrats call “rape.” But taking off that tank top does increase the risk of sexual intercourse that will be later regretted, especially when the tank-topper has been intently mainlining rum and Cokes all evening.

The baby boomers who demanded the dismantling of all campus rules governing the relations between the sexes now sit in dean’s offices and student-counseling services. They cannot turn around and argue for reregulating sex, even on pragmatic grounds. Instead, they have responded to the fallout of the college sexual revolution with bizarre and anachronistic legalism. Campuses have created a judicial infrastructure for responding to postcoital second thoughts more complex than that required to adjudicate maritime commerce claims in Renaissance Venice.

University of Virginia students, for example, have at least three different procedural channels open to them following carnal knowledge: they may demand a formal adjudication before the Sexual Assault Board; they can request a “Structured Meeting” with the Office of the Dean of Students by filing a formal complaint; or they can seek voluntary mediation. The Structured Meetings are presided over by the chair of the Sexual Assault Board, with assistance from another board member or senior staff of the Office of the Dean of Students. The Structured Meeting, according to the university, is an “opportunity for the complainant to confront the accused and communicate their feelings and perceptions regarding the incident, the impact of the incident and their wishes and expectations regarding protection in the future.” Mediation, on the other hand, “allows both you and the accused to discuss your respective understandings of the assault with the guidance of a trained professional,” says the school’s sexual-assault center.

Rarely have primal lust and carousing been more weirdly paired with their opposites. Out in the real world, people who regret a sexual coupling must work it out on their own; no counterpart exists outside academia for this superstructure of hearings, mediations, and negotiated settlements. If you’ve actually been raped, you go to criminal court—but the overwhelming majority of campus “rape” cases that take up administration time and resources would get thrown out of court in a twinkling, which is why they’re almost never prosecuted. Indeed, if the campus rape industry really believes that these hookup encounters are rape, it is unconscionable to leave them to flimsy academic procedures. “Universities are equipped to handle plagiarism, not rape,” observes University of Pennsylvania history professor Alan Charles Kors. “Sexual-assault charges, if true, are so serious as to belong only in the criminal system.”

Risk-management consultants travel the country to help colleges craft legal rules for student sexual congress. These rules presume that an activity originating in inchoate desire, whose nuances have taxed the expressive powers of poets, artists, and philosophers for centuries, can be reduced to a species of commercial code. The process of crafting these rules combines a voyeuristic prurience and a seeming cluelessness about sex. “It is fun,” writes Alan D. Berkowitz, a popular campus rape lecturer and consultant, “to ask students how they know if someone is sexually interested in them.” (Fun for whom? one must ask.) Continues Berkowitz: “Many of the responses rely on guesswork and inference to determine sexual intent.” Such signaling mechanisms, dating from the dawn of the human race, are no longer acceptable on the rape-sensitized campus. “In fact,” explains our consultant, “sexual intent can only be determined by clear and unambiguous communication about what is desired.” So much for seduction and romance; bring in the MBAs and lawyers.

The campus sex-management industry locks in its livelihood by introducing a specious clarity to what is inherently mysterious and an equally specious complexity to what is straightforward. Both the pseudo-clarity and pseudo-complexity work in a woman’s favor, of course. “If one partner puts a condom on the other, does that signify that they are consenting to intercourse?” asks Berkowitz. Short of guiding the thus-sheathed instrumentality to port, it’s hard to imagine a clearer signal of consent. But perhaps a girl who has just so outfitted her partner will decide after the fact that she has been “raped”—so better to declare the action, as Berkowitz does, “inherently ambiguous.” He recommends instead that colleges require “clear verbal consent” for sex, a policy that the recently disbanded Antioch College introduced in the early 1990s to universal derision.

The university is sneaking back in its in loco parentis oversight of student sexual relations, but it has replaced the moral content of that regulation with supposedly neutral legal procedure. The generation that got rid of parietal rules has re-created a form of bedroom oversight as pervasive as Bentham’s Panopticon.

But the post-1960s university is nothing if not capacious. It has institutionalized every strand of adolescent-inspired rebellion familiar since student sit-in days. The campus rape industry may decry ubiquitous male predation, but a campus sex industry puts bureaucratic clout behind the message that students should have recreational sex at every opportunity.

In late October, for example, New York University’s professional “sexpert” set up her wares in the light-filled atrium of the Kimmel Student Center. Along with the usual baskets of lubricated condoms, female condoms, and dental dams (a lesbian-inspired latex innovation for “safe” oral sex), Alyssa La Fosse, looking thoroughly professional in a neatly coiffed bun, also provided brightly colored instructional sheets on such important topics as “How to Female Ejaculate” (“First take some time to get aroused. Lube up your fingers and let them do the walking”) and “Masturbation Tips for Girls” (“Draw a circle around your clitoris with your index finger”). In a heroic effort at inclusiveness, she also provided a pamphlet called “Exploring Your Options: Abstinence,” but a reader could be forgiven for thinking that he had mistakenly grabbed the menu of activities at a West Village bathhouse. NYU’s officially approved “abstinence options” include “outercourse, mutual masturbation, pornography, and sex toys such as vibrators, dildos, and a paddle.” Ever the responsible parent-surrogate, NYU recommends that “abstinence” practitioners cover their sex toys “with a condom if they are to be inserted in the mouth, anus, or vagina.”

The students passing La Fosse’s table showed a greater interest in the free Hershey’s Kisses than in the latex accessories and informational sheets; very occasionally, someone would grab a condom. No one brought “questions about sexuality or sexual health” to La Fosse, despite the university’s official invitation to do so. NYU is not about to be daunted in its mission of promoting better sex, however. So it also offers workshops on orgasms—“how to achieve that (sometimes elusive) state”—and “Sex Toys for Safer Sex” (“an evening with rubber, silicone, and vibrating toys”) in residence halls and various student clubs.

Similarly, Brown University’s Student Services helps students answer the compelling question: “How can I bring sex toys into my relationship?” Brown categorizes sex toys by function (“Some sex toys are meant to be used more gently, while others are used for sexual acts involving dominance and submission . . . such as restraints, blindfolds, and whips”) and offers the usual safe-sex caveats (“If sharing sex toys, such as dildos, butt plugs, or vibrators, use condoms and dental dams”). UCLA’s Arthur Ashe Student Health and Wellness Center advises on how a man might “increase the amount of time before he ejaculates”; Tufts University’s 2006 Sex Fair featured a “Dildo Ring Toss” and dental-dam slingshots; and Barnard College suggests that participants in sadomasochistic sex, “where ‘no, please don’t’ . . . can be a part of the fun,” agree on a “safeword” that “will stop all play immediately.” A Princeton student who thinks that a “docking sleeve” may be some kind of maritime hardware, or a “suction device” something used for plumbing, had better bone up, so to speak, before playing the school’s official “Safer Sex Jeopardy” game, because these objects are in the “grab bag” categories of penile toys and nipple toys, respectively. Encyclopedic knowledge is advisable: game developers list six types of vibrators, including the “rabbit vibrator,” and eight kinds of penile toys, including the “pocket pussy.”

By now, universities have traveled so far from their original task of immersing students in the greatest intellectual and artistic creations of humanity that criticizing any particular detour seems arbitrary. Still, the question presents itself: Why, exactly, are the schools offering workshops on orgasms and sex toys instead of on Michelangelo’s Campidoglio or Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin? Are students already so saturated with knowledge of Renaissance humanism or the evolution of constitutional democracy, say, that colleges can happily reroute resources to matters readily available on porn websites?

Strange Bedfellows at William and Mary

Anyone who still thinks of sorority girls as cashmere-clad innocents, giggling as they wait by the phone for that special someone to call, won’t understand much of the campus “date rape” scene. A few incidents at the College of William and Mary, a pioneer in sexual-assault awareness, may correct lingering misconceptions.

In October 2005, at a Delta Delta Delta formal, drunken sorority girls careened through the host’s house, vomiting, falling, and breaking furnishings. One girl ran naked through a hallway; another was found half-naked with a male on the bed in the master suite. A third had intercourse with her escort in a different bedroom. On the bus back from the formal, she was seen kissing her escort; once she arrived home, she had sex with a different male. Later, she accused her escort of rape. The district attorney declined to prosecute the girl’s rape charges. William and Mary, however, had already forced the defendant to leave school and, even after the D.A.’s decision, wouldn’t let him return until his accuser graduated. The defendant sued his accuser for $5.5 million for defamation; the parties settled out of court.

The incident wasn’t as unusual as it sounds. A year earlier, a William and Mary student had charged rape after having provided a condom to her partner for intercourse. The boy had cofounded the national antirape organization One in Four; the school suspended him for a year, anyway. In an earlier incident, a drunken sorority girl was filmed giving oral sex to seven men. She cried rape when her boyfriend found out. William and Mary found one of the recipients, who had taped the event, guilty of assault and suspended him.

But in the fall semester of 2005, rape charges spread through William and Mary like witchcraft accusations in a medieval village. In short succession after the Delta Delta Delta bacchanal, three more students accused acquaintances of rape. Only one of these three additional victims pressed charges in court, however, and she quickly dropped the case.

A fifth rape incident around the same time followed a different pattern. In November 2005, a William and Mary student woke up in the middle of the night with a knife at her throat. A 23-year-old stranger with a prior conviction for peeping at her apartment complex had broken into her apartment; he raped her, threatened her roommate at knifepoint, and left with two stolen cell phones and cash. The rapist was caught, convicted, and sentenced to 57 years in prison.

Guess which incident got the most attention at William and Mary? The Delta Delta Delta formal “rape.” Like many stranger rapists on campus, the knifepoint assailant was black, and thus an unattractive target for politically correct protest. (The 2006 Duke stripper case, by contrast, seemingly provided the ideal and, for the industry, sadly rare configuration: white rapists and a black victim.)

Stranger rapes also provide less opportunity for bureaucratic expansion. After the spate of “date rapes,” William and Mary’s vice president for student affairs announced that the school would hire a full-time sexual-assault educator, in addition to its existing sexual-assault services and counseling staff and numerous sexual-assault awareness organizations. Freshmen would now have to attend a gender-specific sexual-assault awareness program. None of this new apparatus—for instance, the “Equality Wheel,” which explains the “dynamics of a healthy relationship”—has the slightest relevance to stranger rapes.

However, the cross-currents of campus political correctness are so intense that they produce some surprising twists. William and Mary’s sexual-assault resources webpage invites visitors to “listen to what people affected by sexual assault are sharing.” It then offers ten audio accounts of sexual assaults, exactly half of which are male. “My experience came very close to killing me,” one man reports. One would need the skills of a Kremlinologist to interpret this gender lineup, and the site doesn’t explain who exactly these voices are—but it’s hard to escape the impression that William and Mary has admitted either a huge gay community or some very beefy women. Diversity politics, gay politics, and the sexual-assault movement produce strange bedfellows.

Columbia University’s Go Ask Alice website illustrates the dilemma posed by a college’s simultaneous advocacy of “healthy sexuality” and of the “rape is everywhere” ideology. Go Ask Alice is run by Columbia’s Health Services; it answers both nonsexual health queries and such burning questions as: “Sex with four friends—Mutual?” and “Will it ever be good for me?” (from a virgin). In one post, titled “I’m sure I was drunk, but I’m not sure if I had sex,” Alice takes up the classic hookup scenario: a girl who has no recollection of whether she had intercourse during a drunken encounter and now wonders if she’s pregnant. Alice’s initial reaction is pure hip-to-free-love toleration: “Depending upon your relationship with your partner, you may want to ask what happened. Understandably, this might feel awkward and embarrassing, but the conversation might . . . help you to understand what happened and what steps you might decide to take.” Absent that pesky worry about insemination, there would presumably be no compelling reason to engage in something as “awkward and embarrassing” as a post-roll-in-the-hay conversation.

But then a shadow passes over the horizon: the date-rape threat. “On a darker note,” continues Alice, “it’s possible your experience may have been non-consensual, considering that you were drunk and don’t remember exactly what happened.” Alice recommends a call to Columbia’s Rape Crisis/Anti-Violence Support Center (officially dedicated to “speaking our truths about sexual violence”). Alice’s advice shows the incoherence of the contemporary university’s multiple stances toward college sex. It’s hard to speak your truths about sexual violence when your involvement with your potential date-rapist is so tenuous that it’s awkward to speak to him. And the support center can’t know whether the encounter was consensual. But Alice declines to condemn the behavior that both got the girl into her predicament and erased her memory of it.

The only lesson that Alice offers is that the girl might—purely as an optional matter—want to think about how alcohol affected her. As for rethinking whether she should be getting into bed with someone whom, Alice presumes, she would be reluctant to contact the next day, well, that never comes up. Members of the multifaceted campus sex bureaucracy never seem to consider the possibility that the libertinism that one administrative branch champions, and the sex that another branch portrays as rape, may be inextricably linked.

Modern feminists defined the right to be promiscuous as a cornerstone of female equality. Understandably, they now hesitate to acknowledge that sex is a more complicated force than was foreseen. Rather than recognizing that no-consequences sex may be a contradiction in terms, however, the campus rape industry claims that what it calls campus rape is about not sex but rather politics—the male desire to subordinate women. The University of Virginia Women’s Center intones that “rape or sexual assault is not an act of sex or lust—it’s about aggression, power, and humiliation, using sex as the weapon. The rapist’s goal is domination.”

This characterization may or may not describe the psychopathic violence of stranger rape. But it is an absurd description of the barnyard rutting that undergraduate men, happily released from older constraints, seek. The guys who push themselves on women at keggers are after one thing only, and it’s not a reinstatement of the patriarchy. Each would be perfectly content if his partner for the evening becomes president of the United States one day, so long as she lets him take off her panties tonight.

One group on campus isn’t buying the politics of the campus “rape” movement, however: students. To the despair of rape industrialists everywhere, students have held on to the view that women usually have considerable power to determine whether a campus social event ends with intercourse.

Rutgers University Sexual Assault Services surveyed student athletes about violence against women in the 2001–02 academic year. The female teams were more “direct,” the survey reported, in “expressing the idea that women who are raped sometimes put themselves in those situations.” A female athlete told interviewers: “When we go out to parties, and I see girls and the way they dress and the way they act . . . and just the way they are, under the influence and um, then they like accuse them of like, oh yeah, my boyfriend did this to me or whatever, I honestly always think it’s their fault.” Another brainwashed victim of the rape culture.

Equally maddening must be the reaction that sometimes greets performers in Sex Signals, an improvisational show on date rape whose venues include Harvard, Yale, and schools throughout the Midwest. “Sometimes we get women who are advocates for men,” the show’s founders told a Chicago public radio station this October, barely concealing their disbelief. “They blame the victim and try to find out what the victim did so they won’t do it.” Such worrisome self-help efforts could shut down the campus rape industry.

“Promiscuity” is a word that you will never see in the pages of a campus rape center publication; it is equally repugnant to the sexual liberationist strand of feminism and to the Catherine Mac-Kinnonite “all-sex-is-rape” strand. But it’s an idea that won’t go away among the student Lumpenproletariat. Students refer to “sororistutes”—those wild and crazy Greek women so often featured in Girls Gone Wild videos. And they persist in seeing a connection between promiscuity and the alleged campus rape epidemic. A Rutgers University freshman says that he knows women who claim to have been sexually assaulted, but adds: “They don’t have the best reputation. Sometimes it’s hard to believe that kind of stuff.”

Rape consultant David Lisak faced a similar problem this November: an auditorium of Rutgers students who kept treating women as moral agents. He might have sensed the trouble ahead when in response to a photo array of what Lisak calls “undetected rapists,” a girl asked: “Why are there only white men? Am I blind?” It went downhill from there. Lisak did his best to send a tremor of fear through the audience with the news that “rape happens with terrifying frequency. I’m not talking of someone who comes onto campus but students, Rutgers students, who prowl for victims in bars, parties, wherever alcohol is being consumed.” He then played a dramatized interview with a student “rapist” at a fraternity that had deliberately set aside a room for raping girls during parties, according to Lisak. The students weren’t buying it. “I don’t understand why these parties don’t become infamous among girls,” wondered one. Another asked: “Are you saying that the frat brothers decided that this room would be used for committing sexual assault, or was it just: ‘Maybe I’ll get lucky, and if I do, I’ll go there’?” And then someone asked the most dangerous question of all: “Shouldn’t the victim have had a little bit of education beforehand? We all know the dangers of parties. The victim had miscalculations on her part; alcohol can lead to things.”

In a column this November in the University of Virginia’s student newspaper, third-year student Katelyn Kiley gave the real scoop on frat parties: They’re filled with boys hoping to have sex. She did not call these boys “rapists.” She did not demonize their sex drive. She merely offered some practical wisdom to the “scantily clad” freshman girls trooping off to Virginia’s fraternity row: “That frat boy really is just trying to get into your pants.” Most disturbingly, she advised the girls to exercise sexual control: “So dance with that good-looking guy. If he offers, you can even go up to his room to get a mixed drink. . . . Flirt. But it’s probably a good idea to keep your clothes on, and at the end of the night, to go home to your own bed. Interestingly enough, that’s how you get them to keep asking you back.”

You can read thousands of pages of rape crisis center hysteria without coming across such bracing common sense. Amazingly, Kiley hasn’t received any of the millions of dollars that feminists in the federal government have showered on campuses to prevent what they call rape.

Some student rebels are going one step further: organizing in favor of sexual restraint. Such newly created campus groups as the Love and Fidelity Network and the True Love Revolution advocate an alternative to the rampant regret sex of the hookup scene: wait until marriage. Their message would do more to return a modicum of manners to campus male—and female—behavior than endless harangues about the rape culture ever could.

Maybe these young iconoclasts can take up another discredited idea: college is for learning. The adults in charge have gone deaf to the siren call of beauty that for centuries lured people to the classics. But fighting male dominance or catering to the libidinal impulses released in the 1960s are sorry substitutes for the pursuit of knowledge. The campus rape and sex industries are signs of how hollow the university has become.