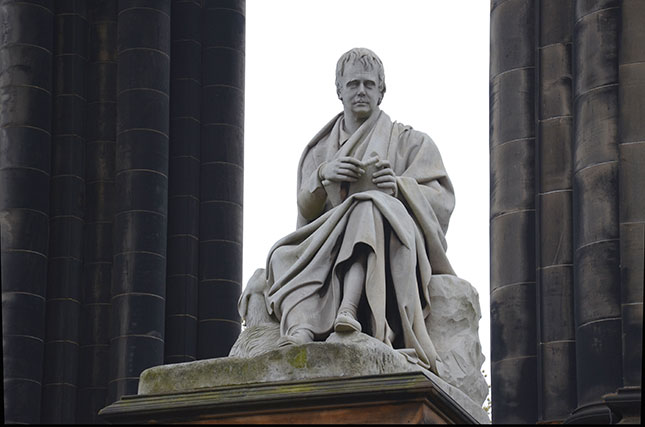

Near the center of Edinburgh stands the tomb of the unread writer. It lies a stone’s throw from the castle with its orbiting birds, high on an extinct volcanic crag; the Old Town with its wynds and tenements; and the pleasant public gardens that replaced a stinking loch full of centuries of detritus. The tomb is an impressive sight, a fine example of the northern Gothic style that gives Edinburgh (“a mad god’s dream,” as the poet Hugh McDiarmid put it) such an enigmatic quality. It was built in the Victorian era, over a decade after the death of the figure it was dedicated to: Sir Walter Scott, whose carrara marble statue, with his dog Maida by his side, huddles under its arches, sheltering from the chill North Sea wind.

For years, I would wait in the shadow of the Scott Monument to catch the bus to work, watching the freezing fog roll in from the sea to engulf the city. Trains could be heard nearby, rattling in and out of Waverley station, named after the eponymous hero of Scott’s debut novel. It is hard to articulate now how colossal a figure Scott was in his lifetime, though the location and grandiosity of his monument give some indication. Faced with the structure, the Belgian crime writer Georges Simenon supposedly gasped, with more than a hint of the apocryphal, “They raised that to one of us? To a writer?” It’s been said many times of Scott that he effectively “invented Scotland,” or at least the image of Scotland in the modern popular imagination. He helped to rehabilitate tartan, for instance, which had been banned since the Jacobite risings, and Highland culture, turning what had once been portrayed as savage and treasonous into an archetype of nobility. Others argue that Scott distorted the authentic nature of Scottish identity and that his supposed patriotism was fatally compromised by his unionism. Few denied the impact of his work. Yet the unavoidable view today is that Scott is a relic of a bygone age. His writings are no longer popularly read as they were and are treated as of primarily academic significance. A crucial pioneer of the historical novel has been consigned to history.

If the Scott Monument stands for anything, it is change. Some figures become trapped in the amber of their time, if not forgotten entirely. One of Scott’s great themes is the echo of history through different eras; he’d have known that the slide into obscurity is more rule than exception. Scott had far to fall, but he has not fallen alone. Outside of academic studies, who reads Mary Jane Holmes or George W. M. Reynolds these days? What is the legacy of Harold Robbins, Arthur Hailey, Ruby M. Ayres, or Gilbert Patten? All sold extraordinary numbers of books, some in excess of Tolstoy and Joyce, some even of Tolkien and Dickens.

Why do they fall? In many cases, they were simply not built to last. Potboilers, penny bloods, airport novels, broadsheets, and dime novels are all designed to be transient. As with newspapers, their throwaway quality is part of their appeal. They kill time, particularly during journeys, and can be guiltlessly knocked about and then discarded. Others are so specific to a particular time that they end up stranded there—books that follow the mode of fashion rather than timeless style. The bias in literary criticism toward tragedy, innately serious and worthy of critical attention, in contrast with supposedly frivolous comedy, has been detrimental to the legacy of many writers. Entire genres can lapse into obscurity as societies change, though it is rare for their spirit to disappear entirely. The age of naval exploration may have passed, but the literature of the era (robinsonades, smugglers’ tales, treasure quests) has not vanished so much as relocated to the outer-space settings of science fiction. Similarly, the serialization model of once-fashionable writers like Charles Reade may have been largely abandoned by fiction, but it thrives on streaming services, where shows utilize the same techniques of cliff-hangers, twists, and delayed gratification.

Other faces are carved onto the Scott Monument. I had time, in my years of waiting, to survey them in the dawn light. Some are of Scott’s mostly forgotten fictionalized characters: Catharine Glover, the Fair Maid of Perth; Jock Dumbie, the Laird o’ Dumbiedykes; Louise, the Glee Maiden. Others are real. Several of the cast of Scottish writers who adorn the structure have remained in fashion, such as the poet Robert Burns. Others have faded away—most unfairly, in the case of the troubled young poète maudit Robert Fergusson, a contemporary of Burns and an acknowledged influence. Who now remembers the Reverend John Home, once a household name in Scotland? Who still reads the picaresque adventures of Tobias Smollett?

It was on the bus from the Scott Monument to the bank where I worked, out on the outskirts of the city, that I first read Christopher Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism (1979). I had not heard of the writer and was dissuaded initially by the generic cover. But the friend who foisted it on me, partly to win a drunken argument, was insistent. He deemed me too idealistic, insufficiently misanthropic, and prescribed the book as a doctor would a dose of treatment to bring me back to my senses. I was certainly impressed by the text’s clarity, especially given the way Lasch weaved through labyrinthine arguments and references, but the bell that it rang was a small one. It lacked the glamour of the contemporary or the arcane, both of which I was drawn to at the time, and I quickly forgot it. Yet as the years passed, with each economic, technological, and political development, I began to realize that the echo of that bell had never subsided.

Almost 30 years after his death, Christopher Lasch occupies a position that would be the envy of any contemporary writer and thinker. Lasch’s charismatic righteousness—lionized today across the board, from The New Statesman to the New York Times to The American Conservative—is matched with mercurial qualities that make him difficult to place on the political spectrum. The writer’s renown has grown steadily since 1979, when a beleaguered President Jimmy Carter consulted him. Writing in 1991, George Scialabba observed: “By now, virtually every political and cultural tendency in recent American history has smarted under Lasch’s criticism.” Remarkably, this process has continued long after his demise. As the Jesuit magazine America put it in 2022, Lasch is a “critic of American life beloved by traditionalist Catholics and Marxists alike.” To understand how this has transpired, we need to examine Lasch’s central work and its mirroring of our time.

The most obvious answer to the question of Lasch’s continued relevance is that he followed the threads of his age into the future. Where would the dominant media, like television, lead? How would technological developments change people? Published in 1979, the book inspired Carter’s infamous “crisis of confidence” speech, delivered that year. Yet upon rereading The Culture of Narcissism, it’s clear that Lasch’s wisdom was less predictive than diagnostic. It is not a question of what some outside force might instill in people so much as how it would amplify and distort what already resides within us. Lasch, a longtime professor at the University of Rochester, saw through and past the vagaries and hubris of his present to recognize age-old patterns of behavior that would join the past and future. This is one of many reasons that he was politically dissident in character, rejecting all-embracing ideas of both tradition and progress. Indeed, much of his work demonstrates the folly of basing our political thought on the seating arrangements of the National Assembly during the French Revolution.

“Narcissism has always been with us, but never had technology allowed such a vast capacity for it to be indulged.”

Though Lasch would move beyond Freud and Marx, especially the latter’s proposals, if not his analyses, he never fully renounced them, and their specters arise repeatedly throughout The Culture of Narcissism. Often, Lasch alternates between the two in rapid succession. At times, he sounds like them. At one point, he proposes that we have been alienated even from our alienation, which seems to follow in the wake of Marx. “The contemporary American may have failed, like his predecessors, to establish any sort of common life, but the integrating tendencies of modern industrial society have at the same time undermined his ‘isolation,’ ” he writes. He then merges this with psychoanalytical theory much more seamlessly and convincingly than others, like the Surrealists, who tried to wed Marx and Freud: “As authority figures in modern society lose their ‘credibility,’ the superego in individuals increasingly derives from the child’s primitive fantasies about his parents—fantasies charged with sadistic rage.”

The most useful quality that Lasch took from both Marx and Freud was the tendency to mistrust surface explanations, to question what people said that they were doing or who they were, especially when it was self-aggrandizing or conveniently expedient, and instead to dig into what they were actually doing and why. In other words, what are their real motivations? Too many commentators, Lasch implies, focus on claims and aftermaths rather than inputs. Often these motivations were concealed, either by “modern industrial society” or by individuals themselves, whether they knew it or not. This restless inquisitiveness animates The Culture of Narcissism.

The image of Narcissus begins, of course, in ancient Greek mythology, with the dazzlingly attractive young hunter who is captivated by his own reflection in a pond and gradually wilts away, leaving a flower where he once knelt. Lasch could have found any number of prime drivers and ills of modern society in those stories. Freud found Eros and Thanatos there, to illustrate the life and death drives of his theories. Writing in Capital (1867), even Marx found a character to encapsulate his belief that economics was at the core of everything: “Modern society, which, soon after its birth, pulled Plutus [the god of wealth] by the hair of his head from the bowels of the earth, greets gold as its Holy Grail, as the glittering incarnation of the very principle of its own life.”

It was Narcissus, however, who struck a chord with Lasch. This is understandable, given the nature of the twentieth century. Though narcissism has always been with and within us, never before had technology allowed such a vast capacity for it to be indulged, via photography, film, and television (and continuing to today, with the Internet). It is tempting to say that we live in an age of mirrors, but a closer analogy would be the funhouse mirror, which continually warps our perceptions of ourselves and others. Narcissus’s pool at least had the gleam of honesty. Yet the real wisdom present in Lasch’s book is that he resists the urge to blame the mirror. However illusory or seductive, the reflection is not at fault. The vast and chaotic inner void needs the mirror.

Narcissism, in other words, was not a mere conceit. Instead, it was a vacuum that demanded to be filled, however temporarily or desultorily, rather than healed. Where and when it took hold, narcissism spoke of a yawning emptiness within the individual and society. Despite what the aura around the book suggests, Lasch is no simple moralist, and he resists condemning the attractions of modern life in and of themselves. Instead, again, he pushes deeper to focus on inputs and outcomes.

That is not to say that he is not scathing. All are criticized: Hollywood and its secular saints; fashion and its impact on other industries; the cult of personality in politics, sports, and culture; the cult of youth promulgated by the advertising industry; the diminishment of the family and elders; the replacement of duty and humility in favor of pride and expediency; the eclipse of meaning by happiness and the eclipse of happiness by consumerism. Yet these developments were neither inevitable nor intrinsic. We willed them as much as we drifted into them.

What all this amounted to, though, was the industrialization of vanity by billion-dollar industries, far beyond anything imagined by the desert rants of Ecclesiastes. Narcissism was both personal catastrophe and big business. As a student of Marx, Lasch recognized the motive, but as a student of Freud, he understood the means. It required the manufacture of insecurity, inadequacy, and neurosis, which these industries would continually promise to abate but would perpetually extend.

To society’s detriment, a number of developments have conspired in the decades since to prove Lasch’s observations increasingly true. One is the monumental rise of supranational corporations and the corresponding mass production of insatiable wants. Another is the emergence of the Internet. Mass online culture happened after Lasch’s book, but he foresaw many of its concerning characteristics, believing already that “we live in a swirl of images and echoes that arrest experience” and that “the proliferation of recorded images undermines our sense of reality.” Online, the news cycle becomes continuous in an ever-cascading present that, rather than leaving us hyper-aware, overwhelms and numbs us, dislocating us from the passage of time and our place in it: “Overexposure to manufactured illusions soon destroys their representational power. The illusion of reality dissolves, not in a heightened sense of reality as we might expect, but in a remarkable indifference to reality.”

Lasch warned that this phenomenon would also sever us from those who came before us and those who will come after us (and our responsibilities to both). “To live for the moment is the prevailing passion—to live for yourself, not for your predecessors or posterity,” he wrote. “We are fast losing the sense of historical continuity, the sense of belonging to a succession of generations originating in the past and stretching into the future.”

With social media and the creation of digital avatars, the narcissist is divorced not just from past and future but from the realities of the present, dwelling instead in the realm of appearances. Success is measured in ephemeral engagement and approval, but this, too, is merely suggestive of the deeper malaise of “a society in which the dream of success has been drained of any meaning beyond itself.” The platform is designed with its perpetual scroll never to conclude or satisfy, aside from the rush of dopamine. Resentment is never far away. The cycle continues, like gears turning.

By way of the Situationists’ The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Lasch sets his sights on the advertising industry for its role in encouraging the culture of narcissism. Key to this is the commodification of the consumer. “In a simpler time, advertising merely called attention to the product and extolled its advantages. Now it manufactures a product of its own: the consumer, perpetually unsatisfied, restless, anxious, and bored,” he writes. This runs disturbingly close to William S. Burroughs’s observation about drug dependency, in Naked Lunch (1959): “The junk merchant doesn’t sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product. He does not improve and simplify his merchandise. He degrades and simplifies the client.”

Yet Lasch is equally lacerating toward compromised attempts to oppose this destructive turn of events. He castigates the prevailing therapeutic climate as merely seeking “the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal well-being, health, and psychic security.” He pours equal scorn on performative political resistance (“Radicalism as Street Theater”), which employs a similar lexicon of individualized self-empowerment and, even when sincere, will fall prey to benevolent tyrants of the managerial class. Lasch’s observation that “bureaucracy transforms collective grievances into personal problems amenable to therapeutic intervention” will prove recognizable to anyone who has raised objective workplace concerns and been responded to with caring-sharing attention, with a very deliberate emphasis on the subjective: “Would you like to talk to someone about your feelings?”

Narcissism begins in childhood, and a culture of narcissism will seek to keep its citizenry in a state of arrested development. It is tempting to blame upcoming generations, seeing a puritan illiberalism in the young, reminiscent of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible (1953): “We are what we always were in Salem, but now the little crazy children are jangling the keys of the kingdom, and common vengeance writes the law!” Characteristically generous even when scornful, Lasch would have no doubt pointed out that “the little crazy children” are a product of their environment and upbringing. The solutions supplied to them are not solutions at all and are not intended to be—they are all designed to continue the dislocation from reality and the narcissistic cycle. They are offered safe spaces, for instance, rather than the genuinely motivational challenges of exposure therapy. The world outside is fabricated to protect the narcissist inside. Looking to the state and corporations like absent parents, and fueled by egomaniacal helplessness, such subjects are vulnerable to predation and profiteering under the guise of kinship and protection. They have, in essence, been betrayed, often by being given what they want rather than what they need. But the true Laschian impulse is to ask what the motivation is to encourage this:

Even when therapists speak of the need for “meaning” and “love,” they define love and meaning simply as the fulfilment of the patient’s emotional requirements. It hardly occurs to them—nor is there any reason why it should, given the nature of the therapeutic enterprise—to encourage the subject to subordinate his needs and interests to those of others, to someone or some cause or tradition outside himself. “Love” as self-sacrifice or self-abasement, “meaning” as submission to a higher loyalty—these sublimations strike the therapeutic sensibility as intolerably oppressive, offensive to common sense and injurious to personal health and well-being. To liberate humanity from such outmoded ideas of love and duty has become the mission of the post-Freudian therapies and particularly of their converts and popularizers, for whom mental health means the overthrow of inhibitions and the immediate gratification of every impulse.

Throughout Lasch’s book, there is a sense that the forces that could oppose or at least mitigate the culture of narcissism are missing. Some have been abandoned, such as religion and the family—and Lasch is not starry-eyed about the realities of either but recognizes the cost in their dismissal. Many politicians and therapists may see narcissism as a useful tool, though Lasch made clear that he believed delusional hubris to be the primary source. “I do not wish to imply a vast conspiracy against our liberties,” he writes. “These things have been done in broad daylight and have been done, on the whole, with good intentions.” The kind of rigorous, antagonistic journalists who would question these developments have been replaced by a commentariat, whose members exemplify the condition itself: “Cultural criticism took on a personal and autobiographical character, which at its worst degenerated into self-display.”

Even the hermitage of literature is not immune, though the narcissism may be a sophisticated reflexive and deniable form: “The confessional form allows an honest writer like Exley or Zweig to provide a harrowing account of the spiritual desolation of our times, but it also allows a lazy writer to indulge in ‘the kind of immodest self-revelation which ultimately hides more than it admits.’ ” Indeed, “the narcissist’s pseudo-insight into his own condition, usually expressed in psychiatric clichés, serves him as a means of deflecting criticism and disclaiming responsibility for his actions.” We may look to Hollywood for moral guidance and to bask “in the stars’ reflected glow,” but the stars are too far away for warmth, and up close they are revealed to be as corrupt and narcissistic as any other cultural sphere, if not more so. Recent revelations have shown us what we’ve always really known about the dream factories. Finally, even escape into the wilds has been sullied: “The conquest of nature and the search for new frontiers have given way to the search for self-fulfillment.” Call it Selfie Above the Sea of Fog.

There is another reason, however, that The Culture of Narcissism has enjoyed a revival. It lies in projection and accusation. Simply put, it is pleasurable and occasionally useful to call other people narcissists. It need not be verified and cannot easily be refuted. It can be wielded against those who suffer and those who succeed with equal impact. As with terms like grifter, normie, shill, hipster, and phony, it is always someone else and never belongs to oneself, echoing Ambrose Bierce’s definition of an egotist in The Devil’s Dictionary (1906): “A person of low taste, more interested in himself than in me.”

Lasch was aware of the attractions of this. “Theoretical precision about narcissism is important,” in part because “the idea is so readily susceptible to moralistic inflation.” He criticized Erich Fromm, who, he claimed, “drains the idea of its clinical meaning and expands it to cover all forms of ‘vanity,’ ‘self-admiration,’ ‘self-satisfaction,’ and ‘self-glorification’ in individuals and all forms of parochialism, ethnic or racial prejudice, and ‘fanaticism’ in groups.”

Uninterested in petty moralism and the supposed superiority that followed from it, Lasch was ultimately sympathetic with those who labored within the culture, admitting: “Narcissism appears realistically to represent the best way of coping with the tensions and anxieties of modern life.” Where there is blame, he directs it toward those who create, and benefit from, the conditions. This is not a malfunction of the system but its triumph:

Modern capitalist society not only elevates narcissists to prominence, it elicits and reinforces narcissistic traits in everyone. It does this in many ways: by displaying narcissism so prominently and in such attractive forms; by undermining parental authority and thus making it hard for children to grow up; but above all by creating so many varieties of bureaucratic dependence. This dependence, increasingly widespread in a society that is not merely paternalistic but maternalistic as well, makes it increasingly difficult for people to lay to rest the terrors of infancy or to enjoy the consolations of adulthood.

One wonders what Lasch would have made of our world today. What would he say about corporate identity politics, environmental millenarianism, iconoclasm and puritan revivalism, populism and the elites, isolationism and the forever war, credentialism and the priestly caste of experts, the marketization of education, sexual developments like incels and Tinder, purity spirals and scapegoating, the commodification of trauma, the gentrification of marginalization? Many subsequent developments highlight the limitations of Lasch’s thought (he underestimated corporate allegiance, to cite one), but he was prescient enough that his books seem to continue their debates. (The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, published in 1994, is another incisive book for our times.)

At their best, and at our worst, it is as if these books have just been written. Lasch warns of the danger of echo chambers, and, when facing the elite of his day, he points out their “narcissistic entitlement—grandiose illusions, inner emptiness.” There is often a feeling that he is with the underdog, especially when criticizing those who usurp that position. He points out the damaging impact that radical pedagogy can have on those whom it claims to liberate, the cruelty of magical thinking, the pseudo-emancipation of “women and children from patriarchal authority . . . only to subject them to the new paternalism of the advertising industry, the industrial corporation, and the state”; the despair behind self-help and its fads—“the ideology of personal growth, superficially optimistic, radiates a profound despair and resignation. It is the faith of those without faith”; and so on. His takes on child development and education are thoughtful. His views on narcissistic parenting and the dread of old age send chills down the spine. If he were around now, he’d be banished by both sides and expelled from the center—a sign that he was likely onto something profound.

Lasch emphasizes the importance of the past and the future, and our responsibility to both in order to begin to have a meaningful life in the present. The tendency in today’s discourse and culture wars, at least, is to seek to control the past through erasure or worship and, by doing so, extend control over what is to come. With its cycles and traps, surprises and tangents, rhymes and revivals, time offers little comfort, except to half-forgotten statues, with the knowledge that history is not yet finished with any of us.