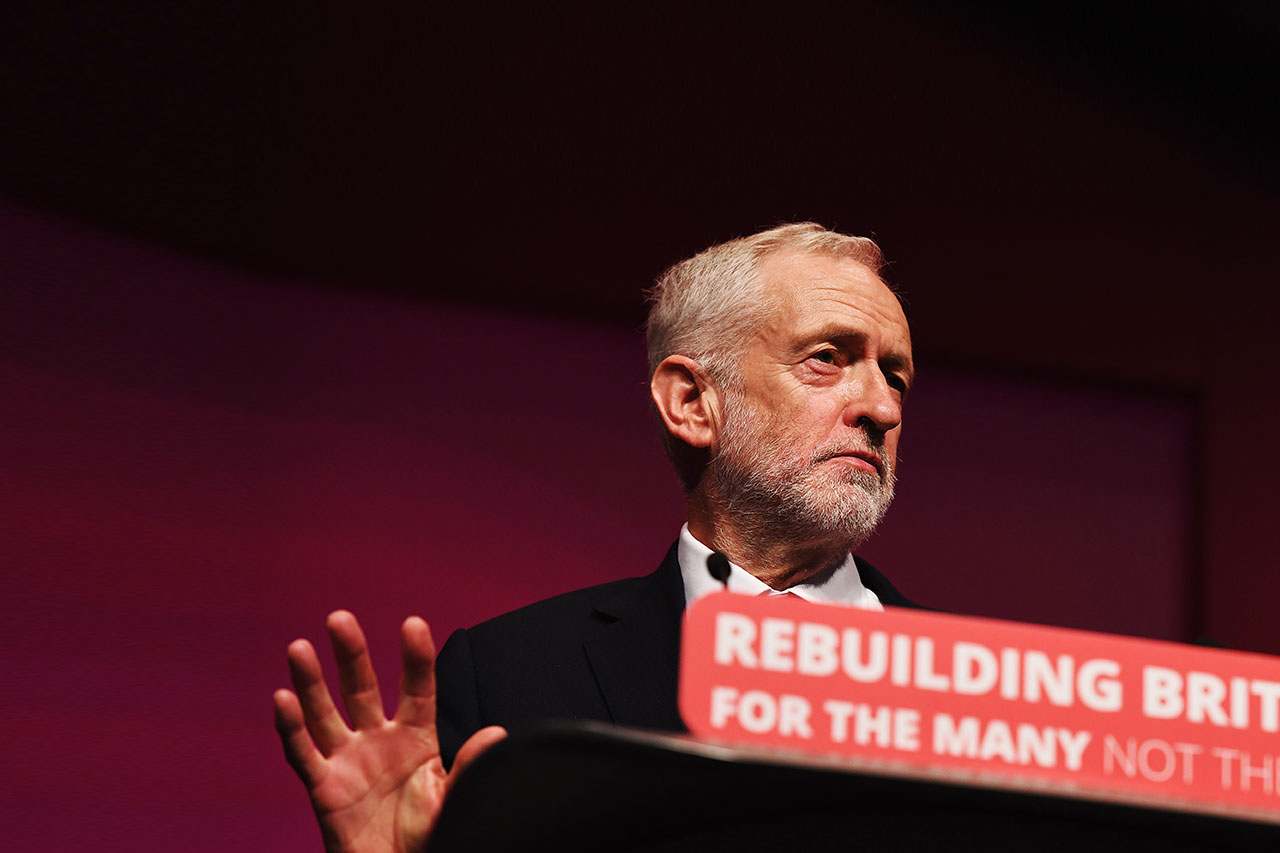

Thanks to the current imbroglio over Brexit, Britain could soon be Venezuela without the oil or the warm weather. The stunning incompetence of the last two Tory prime ministers, David Cameron and Theresa May, might result in a Labour government, one led by Jeremy Corbyn, a man who has long admired Hugo Chavez for having reminded him—though not the people of Venezuela—what governments can do for the poor and the achievement of social justice.

Corbyn’s second in command, John McDonnell, would, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, be in charge of the economy. Only five years ago, he said that the historical figures he most admired were Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky, and though he later claimed that he meant it as a joke, he is not otherwise known as an ironist.

Two days ago, speaking to the party faithful in London, he argued for the nationalization of land. He also favors nationalizing railways and public utilities, which can be done only through rates of taxation so high that they would amount to the nationalization of everything—with a resultant economic collapse—or by outright confiscation, thus destroying any faith in the rule of law for generations. It could also be done by agreeing on a price of sale and then inflating the currency afterward, so that billions will not buy you an egg.

An economic disaster, far from deterring such a government, would be of enormous advantage to it, if you assume that its purpose is the exercise of control in the name of irreversible social and political change. In his speech, McDonnell, who is fluent in Soviet-style langue de bois, said:

The state is a set of institutions; it’s also a relationship, it’s a relationship of dominance, particularly a dominance of working class people about how they have to behave, how they can receive any forms of support or benefits from the state, the parameters in which they operate or even the parameters in which they think, to conform to the existing distribution of wealth and power within our society.

McDonnell’s nationalized industries will be owned and run by the workers, just as they were supposed to be owned and run after the Russian Revolution. The state will wither away, as in Marxist theory, though not in Soviet practice, once all power has been handed to him: “The role of politicians is to open the doors of [the state] and transform the relationship from one of dominance into one of democratic engagement and participation. It’s that whole idea that you gain power to empower.”

McDonnell’s own party will not be just another political party in a competitive, pluralistic polity. Rather, it will be modelled on vanguardist movements from the glorious history of the twentieth century. “We’ve got to convert ordinary members and supporters into real cadres who understand and analyze society and who are continually building the ideas,” explained our future economic minister.

For McDonnell, ideas are “built” rather than thought—the better to be imposed. Not an ignorant man, he knows perfectly well the totalitarian connotation of the word “cadres” in this context; but in any case, he makes clear his commitment to and desire for socialist monomania. Answering Oscar Wilde’s criticism that socialism requires too much of its adherent’s time in the evenings, McDonnell said: “We can’t lose this opportunity by lack of commitment . . . If we waste this opportunity, in 10 or 15 or 20 years, you will be kicking yourself, thinking, ‘Why did I miss that opportunity because I just wanted another night in?’”

It isn’t difficult to predict what will happen. The arrival in power of such men will produce an immediate crisis, which they will blame on capitalism, the world economic system, the Rothschilds, and so forth. They will use the crisis to justify further drastic measures. Already, a Labour Member of Parliament, sitting for a constituency in one of the richest areas of Europe, argues for the wholesale, de facto confiscation of houses. It is but a short step to communal apartments or the nationalization of bathrooms, justified by the bad housing conditions that some people undoubtedly endure. Other charming proposals include the erection of tower blocks of public housing apartments in old villages and leafy suburbs, à la Ceausescu. If everyone cannot enjoy beauty, why should anyone?

Under the British electoral system, this could all be brought about by the vote of 35 percent of the adult population, which would give Corbyn, McDonnell, et al. constitutional legitimacy to do whatever they want. They want to reduce the voting age to 16. They believe not only the Leninist slogan, “the worse the better,” but, where the electorate is concerned, “the more ignorant the better.” This is their one original contribution to socialist theory.

None of this is inevitable, but thanks to the bungling of Brexit, it is considerably closer. For the moment, only Theresa May stands between us and the full socialization of Great Britain—that’s a bit like taking refuge from a hurricane behind a wet bus ticket.