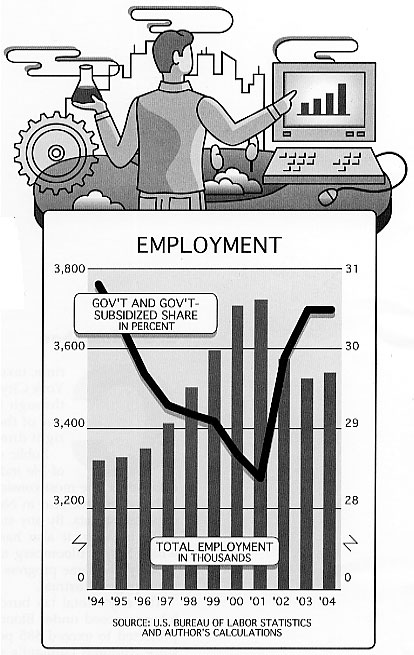

Crime, taxes, and welfare dependency all dropped in New York City from the early 1990s through 2001. But halfway through Michael Bloomberg’s first mayoral term, only one of these three key indicators was still headed in the right direction.

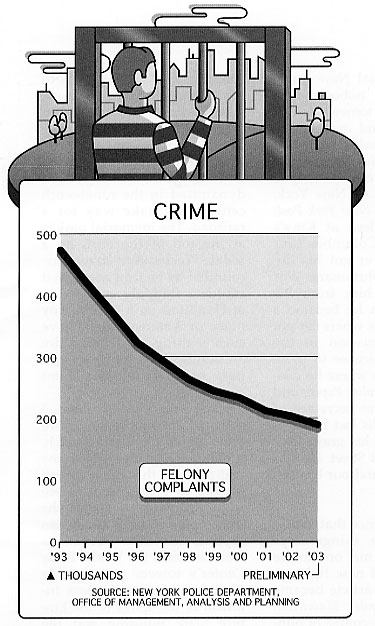

Public safety remains the bright spot among the quality-of-life indicators highlighted on these pages. Major-felony complaints (the most consistent long-term measure of crime) dropped for the 13th consecutive year in New York in 2003, according to preliminary police-department data. By any statistical standard, Gotham is not only the nation’s safest big city; it also has a lower crime rate than many smaller cities, which Mayor Bloomberg takes justified pleasure in pointing out.

Sadly, the same progress hasn’t continued on other fronts, as the charts on these pages illustrate.

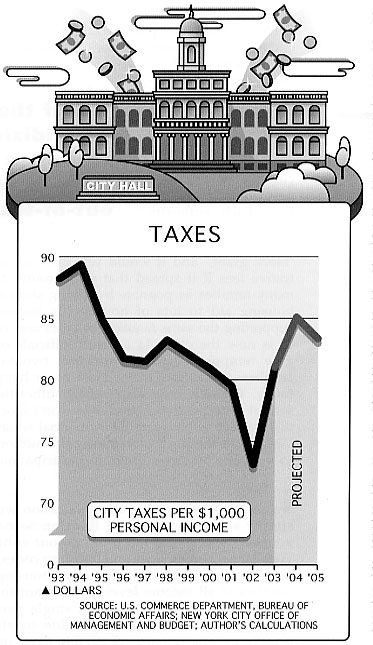

The city’s total tax burden has been rising—reflecting $3 billion in tax hikes imposed under Bloomberg since 2002. In fiscal 2003–04, city taxes are projected to exceed $85 per $1,000 of personal income—the highest level since Rudolph Giuliani’s second year as mayor, almost a decade ago. By comparison, in 2001–02 the same figure had dropped to about $73 per $1,000, the lowest tax burden in 30 years.

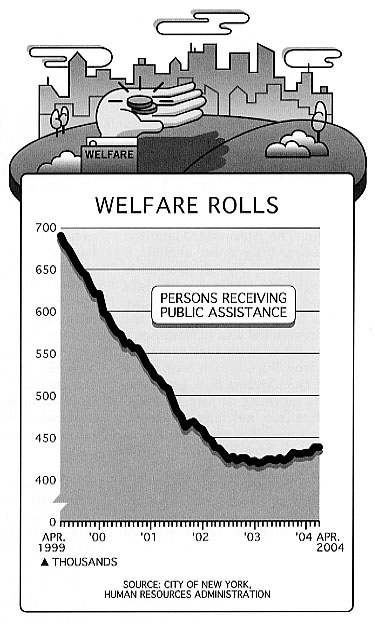

The steady, decade-long shrinkage of New York’s welfare rolls also has come to an end (at least for now). In the fall of 2003, the number of New Yorkers receiving public assistance began rising on a year-to-year basis for the first time in more than a decade—a trend that continued through the spring of 2004. Since February 2003, the public-assistance caseload has increased by more than 19,000. Most of these recipients have exhausted the five-year federal welfare time limit and shifted to the so-called safety-net program funded by state and city taxpayers. Caseload increases continue to be seen in food stamps and Medicaid, as well.

Meanwhile, after years of stagnation, the school system’s ultimate exit measure showed a small performance uptick. Just over 53 percent of the city’s high school class of 2003 graduated on time, an improvement of 2.6 percentage points over 2002. But the number of graduates earning a more demanding state Regents diploma declined by a percentage point, to 34 percent.

There remain striking differences in school outcomes for different ethnic and racial groups. While 73 percent of the city’s white students graduated on time, the on-time high school completion rates of Hispanic and black students were just 47 and 43 percent, respectively. Many of the dropouts were no doubt victims of social promotion in the early grades, a practice that Bloomberg has now pledged to end.

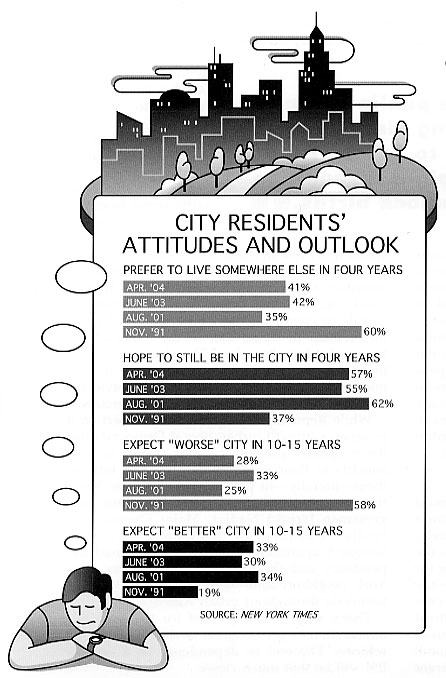

Despite this mixed picture, New Yorkers’ attitudes and outlooks have changed little since last year. In April 2004, 41 percent of New Yorkers said they’d rather be living somewhere else in four years’ time, according to the New York Times’s survey. One-third expected a “better” city in the future, while 28 percent expected things to get worse over the next ten to 15 years. These measures of optimism were all slightly stronger than in 2003, but still below the levels polled in August 2001. They remain significantly better than the mass pessimism reflected in the Times’s survey of 1991, the nadir of the Dinkins era.

As New Yorkers have learned from both good and bad experience, once a trend takes hold, it can be difficult to reverse. Bloomberg’s greatest challenge will be to maintain progress on crime while steering the other indicators back on course. Given some of his harmful fiscal policies, it won’t be easy.