Millennials tend to regard Mad Men as a documentary of the 1950s—three-martini lunches, rampant sexism followed by rampant sex, and political and cultural repression, from the beltway to Elm Street. Of political repression, there is no doubt. Senator Joe McCarthy’s reckless charges of Communist subversion, loyalty oaths, and the Hollywood blacklist—all testify to the decade’s big chill. But cultural repression? In fact, the 1950s were among the most intellectually and creatively provocative periods of the twentieth century.

In that decade, Alan Ginsberg’s influential poem “Howl” appeared, alongside Jack Kerouac’s autobiographical On the Road and Ralph Ellison’s seminal Invisible Man. Short story writers had a flourishing marketplace in which to exhibit their wares, including Collier’s, Esquire, The New Yorker, The Saturday Evening Post, Redbook, and Playboy. Cartoonists worked the same bazaar, and their drawings showed a comprehension of draftsmanship, social perception and—hard as it is to believe today— wit.

Some magazines appeared in paperback-book format, including Discovery, where William Styron’s Long March made its debut, and New World Writing, where a chapter of Catch 22 ran long before Joseph Heller’s novel made its way to the bestseller list. Nobelists Isaac Bashevis Singer, William Faulkner, and Ernest Hemingway regularly showed up in such periodicals, as did Somerset Maugham, J. D. Salinger, Kurt Vonnegut, and dozens of other prominent writers.

Browsers on tight budgets had no trouble assembling a library of classic and contemporary literature, thanks to the paperback divisions of trade publishers. New editions could be purchased for as little as 50 cents, and used ones for even less. Tolstoy, Proust, Mann, Twain, Dickens, Melville—a set of ten such standard authors was available for less than the cost of a tank of gas and lasted a whole lot longer. Every self-respecting candy store and stationer’s had a revolving display of cheap editions.

The covers of these volumes were rather more colorful (not to say lurid) than their clothbound older brothers. This was in accordance with an observation made by a Penguin Books executive: “The general intention of our covers is to attract Americans, who, more elementary than the Britishers, are schooled from infancy to disdain even the best product unless it is smoothly packaged and merchandised.” Snobbish but correct.

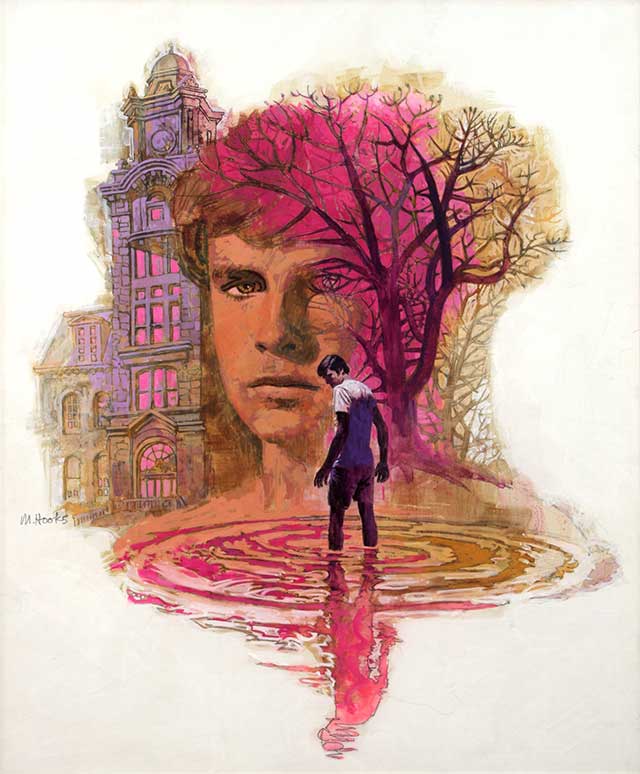

Hence, the emergence of Mitchell Hooks (1923–2013), one of the most influential and unsung artists of the paperback rack. Hooks’s cannily designed covers frequently showed a gun and usually featured a lady, well-endowed, shadowed by trouble, and in desperate need of a protector. The aptly named artist beguiled readers before they had read a word of the author’s prose.

Though Hooks fronted for “serious” writers like Graham Greene (The Confidential Agent) and Paul Bowles (The Sheltering Sky), his specialty was the detective novel. At first, this genre was put down as a shelf of hardboiled time-killers, strictly for addicts of vicarious violence. But the best of them—Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novels, for example—turned out to be something more. As W. H. Auden observed in a festival of commas and aperçus, “Mr. Chandler is interested in writing, not detective stories, but serious studies of a criminal milieu, the Great Wrong Place, and his powerful but extremely depressing hooks should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art.” Critics agreed, and in time the genre became elevated.

Of course, Chandler’s new readers were not enticed by the endorsement of a British poet; they were attracted by the paperback covers. Alas, Chandler produced only seven Philip Marlowe novels, and fans soon gravitated to the fiction of his ardent disciple, Ross Macdonald (né Kenneth Millar). Macdonald offered an homage to Chandler’s creation with his own durable antihero, Lew Archer. In all 18 Archer books the sleuth, a la Marlowe, displays a mordant attitude (“There was nothing wrong with Southern California that a rise in the ocean level wouldn’t cure”) and a cascade of similes (“The past was filling the room like a tide of whispers”; “She was a thin woman of about fifty with a face like a silver hatchet”). Eudora Welty’s fan letter summed up Macdonald’s achievement, not only in character but in structure. Wrote the Pulitzer prizewinner: “In the form you use, the method is pure, the scrupulous search or strategy is the same thing as the truth it’s uncovering—and this is not only compelling but moving. It’s the real beauty of the novels’ construction, to me.”

Early on, other artists were happy to cover the Macdonald series, but they gave way to Hooks’s vibrant lines and luminous palette. Hooks took Archer and Co. into the new millennium, and there could have been no better choice. In Sleeping Beauty, for example, the painter manages to include the shamus, a blonde, a brunette, a dead bird, a human corpse, and an offshore oil rig enveloped in a mist of sun-dazzled yellow and copper—plus the title and the author’s name. Yet there is not a hint of clutter; the personnel, objects, and lettering are clearly and provocatively presented.

Like Marlowe and Archer, Hooks wound up in the movies, doing posters for the first 007 film, Dr. No, and for the Paul Newman feature Hud. But his best work remains the paperback on-ramps to a canon of masterpieces. That kind of literary passage has vanished, leaving nothing in its place. Small wonder, then, that those little volumes of the past have become high-priced collectors’ items. A trip to Google Images, however, will freely reward the public curiosity and the private eye. It will also illustrate, literally, that for generations the 1950s have been caricatured, maligned—and occasionally celebrated—for mostly the wrong reasons.

Top Photo Courtesy of the Museum of Illustration at the Society of Illustrators