In the early morning hours of Friday, January 8, 2016, Mexican marines closed in on the world’s most wanted man: Joaquín Guzmán Loera, better known as El Chapo, a notorious drug trafficker with a net worth estimated near $1 billion. The climactic shootout in Sinaloa, Mexico, took place after Guzmán made a getaway into the sewer system from a house that the authorities had been watching. He was finally apprehended after he reemerged and stole a car. His capture brought to a close six months of humiliation for the Mexican government, which had struggled to explain how Guzmán could escape from a maximum-security prison by walking into the shower, under full view of a video camera, and slipping away through a tiny hole in the floor that led to a 30-foot-deep, mile-long tunnel that had taken perhaps a year to construct. It was the second time that El Chapo had broken out of prison under the noses of Mexican officials. Mexican officials are currently debating whether to hold Guzmán—really, whether they can hold him—or extradite him to the United States, where he faces indictments in multiple federal courts on drug trafficking and murder charges. His organization, the Sinaloa cartel, has smuggled vast quantities of drugs into the United States through elaborate tunnel systems near the border between the two countries.

In Mexico, the confrontation between cartels such as Sinaloa, Los Zetas, and Caballeros Templarios (Knights Templar) has cost nearly 44,000 lives during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto. Human rights organizations counted more than 100,000 deaths during the tenure of Nieto’s predecessor. These and other criminal networks originating in Mexico pay bribes and co-opt police chiefs, mayors, local legislators, and municipal and state police. They infiltrate state institutions, such as courts and attorney offices, especially at the local level, spreading corruption and violence across the country. Though usually defined as “Mexican drug cartels,” they don’t confine their operations to Mexico or their activities to drug trafficking. They extort, kidnap, and murder across Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Los Zetas has perpetrated mass murders in Guatemala, while members of Sinaloa operate in Colombia and Venezuela.

As the United States’ interest in extraditing Guzmán shows, the impact of these activities is often felt beyond Latin America. In 2012, the U.S. Justice Department’s Criminal Division pointed out that at least $881 million in proceeds from drug trafficking, some of which involved Sinaloa in Mexico and the Norte del Valle cartel in Colombia, had been laundered through HSBC Bank USA, without being detected. A U.S. district court requested extradition of former Guatemalan president Alfonso Portillo in 2013, and convicted him in 2014, for laundering millions of dollars through American bank accounts with the help of Jorge Armando Llort, whom he had appointed director of a semi-state-owned bank, Banco de Crédito Hipotecario Nacional. No Guatemalan courts sentenced the bank’s director or the former president.

What few observers realize is that, while El Chapo’s capture made for a dramatic story, the criminal operations of his Sinaloa cartel will proceed almost as if nothing happened. In his notorious Rolling Stone interview with Sean Penn, El Chapo observed: “The day I don’t exist, it’s not going to decrease in any way at all. Drug trafficking does not depend on just one person.”

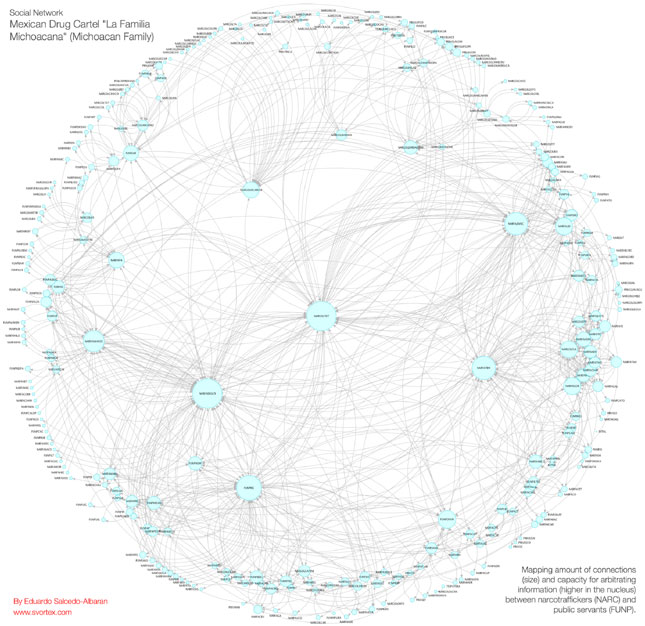

Sinaloa and other criminal cartels have evolved structures that no longer depend on the direction of single leaders. They have become transnational criminal networks—enormous, decentralized, and difficult to map and control. Their operations, too, have become more varied, not only in their criminal activities but in their infiltration and co-optation of legal entities, including government and law enforcement. Even in some countries with strong rule-of-law traditions, they have overcome judicial systems, reconfigured state institutions, and influenced formal democratic processes.

The reach of these groups and the damage they inflict—human, institutional, and financial—represent one of the most pressing challenges for nation-states in the twenty-first century. Up to now, enforcement agencies in nations around the world have focused much of their efforts on the El Chapo model of cartel-busting—that is, trying to capture “most wanted” crime lords, without accounting for the complexity of criminal networks. But the advent of new technological tools that allow a better understanding of these groups and their workings, along with growing awareness of the problem they pose, could lead to a more effective approach.

Though transnational criminal groups operate in varying political contexts, they increasingly share two characteristics. First, they comprise hundreds and sometimes thousands of individuals and subgroups. The result is a resilient criminal infrastructure that doesn’t break down when a criminal leader is imprisoned or killed. No single criminal mastermind makes all the decisions and mobilizes all the resources across these criminal structures.

Second, those hundreds and thousands of people interacting include not only “full-time” criminals but also “legal” players—politicians, bankers, lawyers, public servants, and investors—operating inside formal institutions and manipulating legal functions and procedures. These “gray” agents connect legal and illegal resources. Though this manipulation of institutions is usually defined as corruption, it is better seen as a more sophisticated form of criminal infiltration and co-optation.

Though volumes of documentary and judicial evidence confirm these two characteristics, the data are so diffuse—thousands of names, facts, and locations—that mapping these complex dynamics has been forbiddingly difficult. Instead, these groups continue to be viewed in the context of more traditional notions of organized crime. Investigators, prosecutors, and judges use familiar pyramidal charts to illustrate criminal structures and identify the masterminds apparently at the head of the business. They thus reinforce the misimpression that today’s criminal structures are vertically organized, composed of full-time criminals, and directed by a criminal CEO. For instance, the United Nations defines organized crime as “a structured group of three or more persons, existing for a period of time.” An enormous explanatory gap exists, however, between the concept of a “criminal organization” and a real criminal network, with thousands of lawful and unlawful agents. Organized crime, in most traditional formulations, implies a structure composed only of criminals, with closed and hierarchical systems, and completely isolated from lawful institutions.

Criminal networks, by contrast, are decentralized. Like a virus that never disappears but remains dormant in human cells, some criminal structures mutate, restructure, adapt to changed conditions, and use host organisms—laws and institutions—to reproduce.

In Colombia in the early 2000s, for example, mayors, governors, nearly 40 percent of national legislators, and the head of the national intelligence agency had signed or established agreements with narco-paramilitary commanders of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, or AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia). These agreements consolidated criminal infiltration into Colombian public administration—including local attorney offices and courts—more massive than even Pablo Escobar and his Medellín cartel achieved. Since AUC’s structure supported and received support from officials at every branch of public administration, the basic category of “criminal” was insufficient to analyze the actions of public servants who, for instance, received the criminal group’s help during political campaigns—in exchange for access later—but did not receive bribes directly. Therefore, nothing traditionally understood as corruption occurred. And since elections generally went forward normally, “democracy” remained in force. Enforcement agencies and judicial systems rarely investigate, sanction, or prosecute agents operating within legal institutions and providing money, knowledge, information, financial infrastructure, and protection to criminal actors. In some countries, gray agents working within lawful institutions even enjoy privileged political, economic, or social positions.

Grasping how critical resources flow between lawful and unlawful sectors is more relevant in disrupting cartels than is capturing criminal lords, like El Chapo, who are already overexposed. The false idea that complex criminal structures collapse when a single leader is taken out is sustained by stories like that of the Medellín cartel. In 1993, the Colombian government, Colombian paramilitary forces, the Cali cartel, and the DEA broke up the Medellín cartel by killing Pablo Escobar and rounding up other key members. Since then, other countries have tried to replicate this feat in the hope that similar results would follow. But today’s criminal networks are more complex, resilient, and decentralized than anything that existed in Escobar’s time.

Sinaloa’s successful operation while El Chapo was incarcerated (before his recent escape) showed how the network didn’t depend on one single leader. But while criminal leaders can be quickly replaced, the networks cannot easily replace a compliant governor, say, who provides political favors, or a helpful banker who facilitates money laundering. Such relationships are established and maintained through more varied means than mere bribes or coercion. It is the gray agents who are the most difficult to understand and analyze, since most of their actions are covered and protected by their seeming legality.

“Criminal leaders can be replaced, but the networks cannot easily replace a governor, say, who provides political favors.”

High officials also often enjoy immunity that hampers investigation and prosecution. In Guatemala, for instance, even blatantly corrupt candidates have been protected with immunity, and the congress has not approved legal modifications to address the problem. Nevertheless, in 2015, one investigation resulted in the resignation and incarceration of President Otto Pérez and Vice President Roxana Baldetti.

Such infiltration is typical of criminal networks around the world. In Bulgaria last year, a Court of Appeal ruling pointed out that one criminal group had victimized more than 100 women through human trafficking for sexual exploitation. The women were sent from Bulgaria mainly to France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. One of the group’s leaders, a former police officer, had links with economically and politically powerful members of Bulgarian society. He invested in soccer teams and was elected municipal councillor while incarcerated, after running for a seat in the National Assembly. The court sentenced him to ten years in prison, but Bulgarian authorities didn’t enforce charges, indictments, or prosecutions against other public servants who clearly had supported the criminal operation.

Over the last decade in South Africa, the gang of Dawie Groenewald arranged for veterinarians and other “legal” agents to facilitate permits for hunting and exporting rhinoceros parts as trophies—a scheme specifically established to traffic rhino horns, which, in Vietnam and Hong Kong, have a higher value than gold. Similar criminal structures involving corruption and poachers have almost caused the extinction of the rhinoceroses in Kruger National Park, which shares borders with Zimbabwe and Mozambique. In fact, other criminal groups operating in Kenya reduced the population of white rhinoceroses to just three specimens, which are currently protected day and night by rangers. In these countries, too, officials or other “legal” agents supporting criminal structures almost never face prosecution.

Just as focusing only on criminal agents is mistaken, so, too, is focusing solely on criminal interactions, which, in many cases, are only a small part of a network’s operation. Diversified interactions imply more options for communicating information and transferring resources, which also translates into higher complexity and resilience.

Finally, there is the level of change and manipulation that a criminal network achieves on political and economic institutions, at the public and private levels. Some crimes have deeper institutional effects than others. A common street assault has negative effects on a victim, but it doesn’t modify the social system by itself. Complex criminal networks, by contrast, usually inflict permanent institutional damage. When Colombian legislators established agreements with narco-paramilitary commanders or when Mexican mayors got bribes and favors from criminal networks, the rule of law itself was affected.

Traditional investigative procedures and concepts have proved insufficient for confronting macro-criminal networks. Comprehending the actions of thousands of players across legal and illegal sectors requires gathering, processing, and making sense of huge volumes of judicial and investigative information. A major obstacle to interpreting such vast quantities of data is that the human brain, according to Dunbar’s number, only possesses the capacity for understanding the structure of social networks in which 150 to 200 individuals participate. Beyond this number, we need additional tools.

These tools now exist. Computational techniques such as social-network analysis allow the processing of large volumes of information, while revealing characteristics that cannot be directly perceived by the human brain. For instance, the Vortex Foundation (founded by coauthor Salcedo-Albarán) has designed and applied protocols and software based on social-network analysis to map individual characteristics of each agent or node within a network as well as behaviors of the entire network. These tools have proved vital in developing a sharper understanding of criminal networks and how they operate at transnational, domestic, and local levels in several countries.

In 2005, Colombian police confiscated the computer of AUC’s narco-paramilitary commander “Jorge 40,” revealing the agreements the group had made with candidates, legislators, mayors, governors, and the head of the national intelligence agency. Though AUC had committed mass murders, forced displacement of populations, perpetrated sexual slavery, and even recruited children, the attorney general’s office lacked legal authority to initiate formal investigations against some of the implicated public servants. The Colombian Supreme Court, however, did possess the requisite authority and launched prosecutions under charges of aggravated conspiracy. Under this legal mandate, and through a transitional-justice jurisdiction later designed by the Colombian government, AUC commanders in Colombia turned over huge volumes of information describing names and interactions related to thousands of crimes. Some attorneys and investigators quickly realized that they lacked the technical capacities and tools necessary for making sense of all these data that described systematic crimes. Understanding those complex structures required innovative concepts related to social systems and networks—concepts not restricted to traditional categories of “legal” and “illegal” agents or to traditional crimes of corruption as defined in the penal code. The investigators sought tools and techniques for modeling, mapping, and visualizing complex and diffuse structures.

With its software, Vortex and other firms supported the analysis of information provided by the AUC commanders. The thousands of names and interactions were integrated into models that provided insight into financial and political substructures as well as the most relevant agents and interactions within smaller subnetworks. In November 2014, the Colombian Supreme Court finally handed down judicial sentences against the AUC commanders that incorporated the concepts of criminal networks and reconfiguration of institutions.

We have a long way to go, though, in analyzing and effectively combating criminal networks. Many investigators, attorneys, and judges still proceed using solely the concepts of hierarchical criminal organizations and individual criminal leaders operating in isolation. The deployment of sophisticated tools and methodologies has been relatively limited. Due to a lack of technical capacities or inadequate legislative support, or as a result of corruption or criminal infiltration, even countries with solid law enforcement and judicial systems overlook the critical participation of gray agents in criminal structures. Even in the United States, where some enforcement agencies do apply techniques for modeling and visualizing transnational crime, local and district courts often lack the technical know-how to work with these tools. The situation is even worse in local courts in Latin American or West African countries.

Several scientific, methodological, and judicial challenges must be overcome if these innovative techniques are to be adopted more broadly. The challenges include incorporating concepts of complexity and criminal networks into judicial systems; adopting computational tools for analyzing large volumes of information; and reforming jurisprudence to investigate agreements between politicians, businessmen, and full-time criminals. If investigators, prosecutors, judges, and journalists don’t break out of their old thinking, macro-criminal networks will keep infiltrating and corroding democratic processes and lawful institutions. Of course, we must continue to capture and convict the El Chapos of the world. But the broader answer to combating the scourge of transnational criminality lies in the huge volumes of information, all too often stored in the basements of courthouses, that await our analysis—and action.

Eduardo Salcedo-Albarán, profiled by OZY as “the crime-fighting philosopher,” is the founder and director of the Vortex Foundation, which provides input for policymaking under integrative science principles. He is coauthor (with Luis Jorge Garay-Salamanca)of Drug Trafficking, Corruption and States: How Illicit Networks Shaped Institutions in Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico. Luis Jorge Garay-Salamanca, academic director of the Vortex Foundation, is a member of the Monitoring Commission on Public Policies in favor of the Forced Displaced Population in Colombia.

Top photo: Criminal gangs have extended their reach across national boundaries and into lawful institutions. (JAVIER ARCENILLAS / LUZPHOTO/REDUX)