On paper, at least, the Bloomberg administration’s plans for New York City’s future development are as comprehensive, sophisticated, and visionary as those of any major city in the nation. The City Planning Commission, in cooperation with several sister agencies, has drafted ambitious, far-reaching plans for all five boroughs and taken numerous steps to implement them. The proposals, easily accessible online, are comprehensive and compelling. If ever fully realized, they could make New York the world’s most attractive, livable, and economically vibrant metropolis.

The catch is in the clause if ever fully realized, because it is highly unlikely that they will be. The city’s plans for its physical environment suffer from the same philosophical flaw that pervades all its policies: the assumption that Gotham is so desirable that no price is too high, no burden too great, for the privilege of locating there (or, in this case, building there). During the recent boom years, developers did indeed put up with restrictive regulations and procedural delays that cut into their profits. But after the collapse of Wall Street and the collateral collapse of the city’s real-estate market, it is highly unlikely that they will continue to do so. New York may have to begin acting like other American cities, which welcome with open arms those willing to invest millions of private dollars to expand and renew their physical stock. And a good place for New York’s reorientation to begin is a comprehensive overhaul of its phenomenally complex and outdated zoning ordinance.

Now present in just about every American municipality, zoning was born in New York in 1916. In its first phase, best characterized as “simple rules to guide developers in a rapidly growing city,” New York’s zoning was a crisply designed and straightforwardly implemented scheme. It aimed merely to prevent three kinds of potential development harm: excessive building density, which could prevent light and air from reaching street level; the juxtaposition of highly incompatible residential and commercial structures; and egregious visual assaults on the shared civic landscape. The 1916 ordinance served the city well. Under its rules, much of iconic New York as we know it today was built: Rockefeller Center, Times Square, most of the financial district, and the Woolworth, Chrysler, and Empire State Buildings. So was a lot of the outer boroughs’ highly serviceable residential development (think Forest Hills, Riverdale, the Grand Concourse, and miles of modest but attractive row houses in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx).

In 1961, the Wagner administration replaced the 1916 framework with one mirroring the planning fashions of the day. Reflecting the now-discredited “towers-in-a-park” approach to urban design, New York’s second-phase zoning did away with the 1916 ordinance’s concern with sunlight at street level, replacing it with a new approach to regulating the size of buildings: FAR, the “floor area ratio” between the area of a site and the permissible enclosed volume of a building on that site, an idea that has turned out to be both aesthetically unsound and functionally undesirable. The 1961 ordinance was also far more complex, with 21 zones (compared with five in the earlier law, and eventually swelling to over 50 today, not counting special districts). And it unwisely set aside excessive amounts of land for the city’s shrinking manufacturing sector. New York’s second-phase zoning might best be described as “unworkable rules to prevent developers from building what the market wanted.”

By the late 1970s, the city’s zoning regime had morphed into its third and most pernicious phase, the one we live with today. Call it “exquisitely negotiated rules that allow the richest, most patient developers to build what city planners and the ‘community’ think best.”

Under zoning ordinances anywhere, any proposed structure that doesn’t conform precisely to the zoning rules as written must gain some kind of project-specific government approval, such as an administrative variance or a legislated change in the zoning law. But because New York’s 1961 rules seldom allow builders to erect the projects that they believe the market wants, almost every significant development needs project-specific city approval.

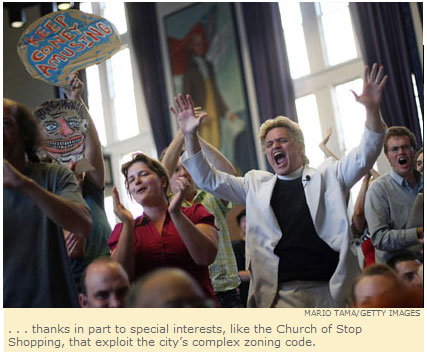

To secure it, three sets of actors need to agree. First, of course, there is the developer, along with its financiers. Second, we have representatives of New York City’s government—professional planners in the City Planning Department, their superiors on the mayorally appointed City Planning Commission, and economic development officials—all of whom have very specific ideas about what should be built and where. Finally, the procedural requirements attending all zoning exceptions—notably, the city’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, adopted in 1975, and its City Environmental Quality Review, enacted in 1977—invite interest groups to weigh in on the merits of development proposals. At the neighborhood level, one finds community boards and ad hoc “coalitions” formed solely for the purpose of killing or recasting proposed projects. Outside the neighborhood, the players are such powerful groups as the Municipal Art Society, the self-appointed guardian of New York’s civic and aesthetic interests, and Acorn, an advocacy group that invariably attempts to extort some “affordable” housing (read: subsidized by the developer). Typically, by the end of negotiations, many proposed projects never see the light of day or are transformed in ways that are economically or functionally undesirable.

There are many different permutations in this three-way dance, but four highly publicized projects in New York City illustrate the tortuous dynamics that bedevil most new development proposals. In each instance, current zoning provisions couldn’t accommodate the kind of development being sought, the project could be realized only by changing some aspect of the standing zoning rules, and the necessary zoning changes had to make their way through a painful approvals process. These cases also illustrate the various ways in which the development process is distorted when private-sector initiative and economic judgment wind up overridden by officials and citizens with no personal financial stakes in the outcome.

The first example is Coney Island. Tattered and shabby, this legendary beachside playground for working-class New Yorkers has clearly fallen on hard times, with most of its famous rides shuttered and summer beach attendance way down. You would think that the city and the community would be thrilled if someone would come forward to redevelop the place, especially if it could happen with little in the way of taxpayer support. But after a regional developer, Thor Equities, bought Coney Island’s Astroland amusement park and adjacent properties, hoping to build a twenty-first-century amusement-park complex that included hotels and large retail facilities, it got nothing but grief. The city’s planners and the local community scorn the hotels and big-box stores—which the developer believes are necessary to make the project economically viable—preferring more amusements and “affordable” housing. The Municipal Art Society, meanwhile, doesn’t like either the city’s or the developer’s ideas and wants a Disneyland-scale amusement park.

Put aside the question of which proposal has the greatest merit. The problem is that the city and the interest groups are blocking a welcome, and presumably economically feasible, undertaking to rebuild one of the city’s most symbolically resonant neighborhoods—an undertaking, moreover, by a private corporation refreshingly relying on its own assets and financing rather than on a taxpayer handout. Why the resistance? Because both the city and the “community” consider their visions for the site superior to the developer’s. In the end, either nothing will be done with Coney Island, or its rebuilding will take years longer.

For another example of thwarted developer-initiated development, look at Fordham University’s proposal to expand its Lincoln Center campus substantially. Here again, we have a private (in this case, a nonprofit) entity wanting to undertake—without city help—a beneficial project that would not only add high-quality physical facilities to one of Manhattan’s key districts but also contribute to the city’s economy in one of its important growing sectors: higher education. The city’s planning department gave the project a green light, but the neighborhood opposed it, on the grounds that the proposed buildings were too dense and too tall—though, if anything, they were smaller than most structures recently erected in the area. When the project came up for review, activists besieged the local community board, which unanimously withheld its approval. Fordham seems willing to scale its project back to win the required approvals, and, at this point, it looks as though the project—diminished by several hundred thousand square feet—may eventually move forward. Even so, we shouldn’t be pleased about the evisceration of such a valuable addition to New York’s economy and physical plant.

Even as market-validated, unsubsidized projects like Thor’s and Fordham’s get derailed, city and state planning and economic-development agencies, deploying hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars and formidable land-acquisition powers, work mightily to get developers to build what and where they otherwise wouldn’t. In Willets Point, Queens, a dismal precinct of marginal factories and small industry, the city’s Economic Development Corporation is prepared to buy vast tracts of land and deploy tax subsidies to create an ambitious mixed-use commercial and residential district. Predictably, significant local opposition has arisen, mainly from the area’s small businesses. Until now, the city’s planners have shown far greater interest in the project than any developers have, making city government the community’s primary antagonist and putting the plan’s economic feasibility in serious doubt.

Further along, at the edge of downtown Brooklyn, planners have conceived another elaborate mixed-use development of housing and commercial structures, called Atlantic Yards, centered on a new basketball stadium for the New Jersey Nets. The lead developer, Forest City Ratner, would never have undertaken the project without half a billion dollars in subsidies, as well as assistance in land acquisition, from the city and state. Despite a solid government-developer alliance, the project has been held up—and perhaps permanently wounded—by vociferous community contentions that it’s too big and doesn’t include enough affordable housing.

The dysfunction of third-phase zoning was long disguised by New York’s dramatic economic and demographic revival over the last two decades. Since the city’s nadir in the late 1970s, its population has grown by over 1.2 million, and its economy, by the eve of the current meltdown, had gained 1 million jobs. Outsize bonuses fed Wall Streeters’ desire for luxurious apartments; outsize profits fed their bosses’ desire for luxurious offices; and a vast influx of immigrants brought new demands for residential and commercial space to uptown Manhattan and the other four boroughs. All this fueled what seemed an insatiable appetite for new development throughout the city.

Developers, at least the best-capitalized ones, were willing to put up with long procedural delays and with high project costs, which they were able to pass on to purchasers or tenants. City hall, for its part, began to believe that it could make any demands it wanted on developers and that the market would bear the cost.

Negotiated zoning didn’t make much sense even in the heady days of New York’s economic boom. Today—with an excess of recently built residential and commercial space, a severely distressed housing market, and huge job losses—we no longer have a development environment in which planners and community activists can call the shots. If the city is to have any hope of increasing and revitalizing its physical stock, its approach to zoning must change radically. New York needs to move from third-phase negotiated zoning to what I will call Phase Four: “simple rules that promote the development of economically feasible, unsubsidized projects with high standards of urban design and respect for neighborhood identity and scale.”

The objective of comprehensive rezoning should be to spur building and rebuilding. Fourth-phase zoning, therefore, must be designed to facilitate the rapid development of any reasonable project anywhere in the city—even in its densest sections—without requiring subsequent review and approval, other than by the buildings department to assure conformity to whichever specifics of the new zoning code do apply to a particular project.

This will require a massive behavioral reorientation on the part of the three key actors in the development process. City officials, while able to shape the form and character of the city’s districts when they establish the underlying zone specifications, must be willing to give up their power to design, actively or reactively, each significant development. Neighborhood residents and citywide advocates, while likewise playing a major role in agreeing to the initial rules, must be willing to give up their ability to block or modify individual proposals. Perhaps the greatest behavioral reorientation will have to come from the builders. Even as they complain about the costs and delays of the current system, they have become convinced over the years that they can always negotiate their way to a more desirable development outcome. (Indeed, the prices they pay for sites often reflect not the returns that those sites would yield under current zoning restrictions, but what they would yield after negotiated exceptions to those restrictions.)

To ensure that fourth-phase zoning can operate with a minimal level of site-specific review and revision, it needs to jettison some of the failed ideas of the 1961 ordinance in favor of rules that promote good urban design and respect neighborhood scale and character. For one thing, building density should no longer be regulated according to floor area ratios. FARs are easily manipulated, letting developers build structures wildly out of scale with their surroundings; sometimes, for instance, developers are allowed to include in the ratio the area of adjacent sites that they own. New York should instead constrain structure density and scale, as most traditional zoning codes do, with specific height and bulk specifications—or else, as the original 1916 law did, with a “sky exposure plane,” an imaginary diagonal drawn from street level that required progressively greater setbacks as building height increased. (Hence the resemblance of many classic New York buildings to ziggurats or wedding cakes.)

Another part of the current zoning regime that should be scrapped is the way it treats use restrictions. Under a traditional zoning ordinance, like New York’s 1916 law, a municipality establishes a broad set of permissible “uses”—usually, several categories of residential, commercial, and industrial facilities—and specifies the geographic districts in which they are permitted. Further, because it is impossible to know how much land should be devoted to each use, uses are customarily organized in a hierarchy based on their “external costs,” with less harmful activities generally permitted in districts zoned for more harmful ones. A factory, for example, would not be permitted in a commercial or residential zone, since it might degrade the quality of life there, but a retail complex could open in a manufacturing zone, and homes could go anywhere.

In 1961, New York abandoned the hierarchical-use principle and began specifying precisely which uses could operate in each zone. The idea was to protect manufacturing in the Garment District and along the East River by preventing residential development there. But the inflexibility of the new approach, exacerbated by the current ordinance’s voluminous schedule of uses, has been one of the leading causes of project-specific negotiation. Fourth-phase zoning should be organized around a limited number of broad use categories, and it should return to the traditional hierarchical practice.

Something like this new zoning regime was proposed nine years ago, during the Giuliani administration, with the initiative led by Joseph Rose, then chairman of the City Planning Commission. The effort failed because of the vehement opposition of the real-estate industry (mainly at the behest of its best-capitalized developers), which was convinced in those days that despite the time and money lost in zoning negotiations, the old rules would permit them—after the negotiations were concluded successfully—to build taller structures than the proposed new ones would. But that was back when the city’s economy and real-estate market were booming and a fair amount of development made it through the dysfunctional zoning process. Now, during a moment of high economic anxiety and stalled development, may be a more opportune time to revisit zoning reform.

Further, though Mayor Giuliani accomplished a great deal, notably in reviving New York’s economy and lowering its crime rates, reordering the city’s physical environment was not among his priorities. Mayor Bloomberg, by contrast, cares a great deal about New York’s physical condition, as evidenced by his championing of physical renewal efforts across all five boroughs, his issuing of PlaNYC (a vision for New York’s physical condition in 2030), and the quality of his appointments to the city’s planning and housing agencies.

To the Bloomberg administration’s credit, its City Planning Department has sought, in many parts of the city, to replace strictly project-specific discretionary action with legislated rezoning, initiating more local zoning changes than at any time since the passage of the 1961 ordinance. Yet many of these rezonings just amount to negotiated zoning at a more institutionalized scale. If the administration really wants to give New York a face to match its grandest twenty-first-century aspirations, it must recast zoning comprehensively, adopting a new ordinance that promotes the development of market-validated projects all over the city, with rules designed to expand the city’s economy, enhance its quality of life, and reflect the highest standards of contemporary urban design. That should be something that the city’s government, real-estate and development interests, and specialists in planning and zoning can easily agree about.

The Downtown Development Drag

Nearly eight years after al-Qaida destroyed the World Trade Center, uncertainty at the site still delays downtown’s recovery. Developer Larry Silverstein holds the right to rebuild much of Ground Zero’s commercial real estate under a lease he signed with the site’s owner, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, six weeks before 9/11. But years of political dithering have kept Silverstein from building. New York, under Governors George Pataki, Eliot Spitzer, and David Paterson and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, could never quite figure out what to build or how to build it. Pataki became infatuated with fanciful office-tower designs by starchitect Daniel Libeskind. Bloomberg questioned downtown’s viability as an office hub, withholding rebuilding funds until Silverstein surrendered the right to construct two of his original five towers, including the much-heralded Freedom Tower, to the Port Authority.

Government delay has cost more than time. Silverstein needs outside financing to build his remaining towers. (The insurance money that he got after the attack has dwindled, much of it paid out in rent to the Port Authority, and was never enough to rebuild completely, anyway.) Three years ago, he likely could have found it in the private market. Today, in a deep recession precipitated by the meltdown of New York’s prime industry, it’s impossible to raise money for speculative office towers without government guarantees. So Silverstein wants more than $3 billion in such guarantees to build his towers. The Port Authority will offer about a third of the guarantees needed, but it wants Silverstein to put up additional money, and it wants the city to chip in, too, before it will consider more.

But the Port Authority and the state, though they have caused many of the delays, shouldn’t try to fix their mistakes by providing financial guarantees of office buildings, which should be a private-sector enterprise—especially at a time of huge budget deficits. Direct government involvement in Ground Zero’s towers pushes the city’s other private developers into greater competition with the government, which can undercut commercial rents. If commercial tenants can take advantage of government-subsidized rates downtown, prospects for real-estate development elsewhere in the city could suffer. (None of this is to say that the Port Authority shouldn’t restructure its lease to offer Silverstein more time to complete his buildings; it’s even possible that the authority will end up owing Silverstein money for the continuing delays.)

The state, the authority, and the city should instead focus on their real job: building downtown’s Fulton Street subway hub, the PATH train station for New Jersey commuters, and other public infrastructure at and near Ground Zero. Once the private sector sees that government can build the infrastructure that the site needs, private financing will materialize for the office towers, just as it will for other projects now on hold across the city. To doubt that the private sector will eventually build office space in a major New York business center is to doubt the very possibility of New York’s recovery.

—Nicole Gelinas