Every day for the last 200 years, boats gliding along the wide Potomac have blown their horns or clanged their bells as they pass Mount Vernon, in festive tribute to the estate’s revered creator, George Washington. The tradition began, legend has it, when Admiral George Cockburn, sailing back from torching the city of Washington in the War of 1812, tolled his flagship’s bell as he passed Mount Vernon in 1814, though whether as a chivalrous salute to the memory of an officer of world-historical genius or as a sarcastic taunt after burning the city that bore the great general’s name legend doesn’t say.

What is certain is that one such foghorn blast on an autumn night in 1853 startled a South Carolina lady returning home by steamer from Philadelphia, and she came up on deck to see what the commotion was about. In the bright moonlight, she saw the cause all too plainly: Mount Vernon—but a Mount Vernon moldering into ruin, its veranda sagging, its untended lawns waist-high. “I was painfully distressed at the ruin and desolation of the home of Washington,” Louisa Cunningham wrote to her daughter. “It does seem such a blot on our country!”

That letter set in motion an extraordinary drama of historical preservation that will seem almost incredible to the 1.1 million visitors each year who see today’s superb Mount Vernon, sparkling with reverent care and bustling not just with tourism but with world-class scholarship. And the same is true of the 440,000 annual visitors to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, also designed, like Mount Vernon, by an amateur-architect Founding Father and embodying in concrete form its builder’s deepest longings and ideals. (See “Monticello’s Shadows,” Autumn 2007.) The home of the author of the Declaration of Independence—perhaps America’s most beautiful house—was once similarly falling into ruin, before being saved in the most unexpected, almost operatic, way and transformed, like Mount Vernon, into one of the nation’s premier private philanthropies.

As soon as Ann Pamela Cunningham, then 37, read her mother’s letter, she avidly seized the challenge of rescuing the Father of His Country’s estate—and rescuing herself in the process. She had damaged her spine at 16, when her horse threw her as she galloped across her family’s sprawling plantation. Though she wasn’t paralyzed, the pain that had plagued her ever since was beyond her eminent doctors’ powers to cure and often kept her bedridden. Her mother’s suggestion that “the women of this country” should save Mount Vernon, “if the men could not do it,” galvanized the lonely spinster into action and gave her an escape from her bleak endurance.

Like most movement leaders, she began with a manifesto, “To the Ladies of the South.” Appearing above the byline of “A Southern Matron” in the Charleston Mercury on December 2, 1853, it seethes with anger about more than Mount Vernon’s sorry state. Because Congress, a pack of “jobbers and bounty-seekers,” she wrote, “of office-aspirants and trucklers, of party corrupters and corrupted—all collecting like a flock of vultures to their prey,” has refused to buy Washington’s estate as a national monument, she and other ladies from “a region of warm, generous, enthusiastic hearts, where there still lingers some unselfish love of country and country’s honor, some chivalric spirit, . . . some reverence for the noble dead,” will have to do the job themselves. Otherwise, “the shrine of true patriot- ism” will end up “surrounded by blackening smoke and deafening machinery, where money, money, only money ever enters the thought, and gold, only gold, moves the heart or moves the arm!” This devoted South Carolinian wrote, remember, just a month before Congress introduced the pro-slavery Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise, laid the groundwork for a transcontinental railroad (hence the talk of smoke and machinery), raised to toxic levels the sectional rancor that Cunningham’s manifesto expresses, and brought the Civil War a giant step closer.

For all her antibusiness rhetoric, though, what Cunningham proposed was a commercial transaction: buying real estate, for money. Trouble is, the owner, John Augustine Washington III, the general’s great-grandnephew, didn’t want to sell it to her. When Martha Washington died in 1802, only three years after her husband, the house had gone to the general’s nephew and residuary legatee, Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington, who left it to his nephew, John Augustine Washington II, from whom his sensitive-faced son inherited it in 1850. John Augustine III most certainly wanted to be rid of Mount Vernon, since the expense of entertaining swarms of uninvited tourists with the hospitality that Virginia’s gentlemanly code required was ruining him, along with his house. But he believed no less piously than Cunningham that the estate should be preserved as a fitting, official memorial to his illustrious ancestor; and to him, that meant that the government—if not of the United States, then of Virginia—should buy it for $200,000 and spruce it up. So he turned down Cunningham’s request, made shortly after she published her manifesto, to consider selling the house to her and the group she was forming to raise the necessary funds, just as he reportedly had turned down a bid of $300,000 from a developer.

Five years later, matters looked very different. An undeterred Cunningham had continued to raise money and had enlisted a powerful ally: the intense, charismatic Edward Everett, a former congressman, Massachusetts governor, Harvard president, ambassador to England, and—briefly— secretary of state and U.S. senator. He then became a popular and highly paid orator—so celebrated that in 1863, toward the end of his life, he gave the keynote address at the dedication of the Gettysburg Cemetery, a two-hour speech unluckily vaporized into oblivion by the 270 immortal words Abraham Lincoln uttered to close the proceedings. After hearing Everett speak on the greatness of Washington in Richmond in 1856, Cunningham told him of her campaign, and he offered on the spot to donate his fees from the rest of his speaking tour to her group. In 1858, he signed on to write a year’s worth of weekly columns on American history for the New York Ledger, if the paper would donate $10,000 to Cunningham’s group, now officially chartered as the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA) of the Union. So when Cunningham wrote to John Augustine Washington in March 1858 to tell him that the Virginia legislature, like the U.S. Congress, had just voted down a bill to buy Mount Vernon, and to renew her original offer, she was also able to report that she already had in hand more than enough to make a sizable down payment on the $200,000.

In that case, John Augustine wrote back, “believing that after the two highest powers in our country, the Women of the land will probably be the safest as they will be the purest guardians of a national shrine,” he would be pleased to accept Cunningham’s offer, and on April 6, he signed a sales contract for the house, 200 acres of land, and the general’s tomb. By February 1859, Cunningham had paid him $100,000, made up of contributions from Everett’s munificent $69,551.06 down to the equally hard-earned $4.18 given by the newsboys of New York City. On George Washington’s birthday, February 22, 1860, with the full $200,000 paid, John Augustine Washington moved out of Mount Vernon, and Ann Pamela Cunningham moved into a drafty, leaky house that contained nothing but the key to the Bastille that Lafayette had sent his beloved mentor; Washington’s big world globe, leather saddlebags, pistol holsters, and fire buckets; the original clay model of the bust that celebrated sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon had modeled of the general in 1785; and the opulent London-made harpsichord that President Washington had bought for his granddaughter, Nelly Custis, in 1793. Martha Washington’s great-granddaughter, Mrs. Robert E. Lee, had sent the instrument back to Mount Vernon in 1859, when she heard that the MVLA intended to make the house a shrine—a heartbreaking story, when you remember that, less than two years later, her husband would try to break up the Union that Washington had labored so long and faithfully to found.

Joining Cunningham in the nearly empty house was her recently hired secretary, Sarah C. Tracy, 39, a quick-thinking native of Troy, New York, who had worked as a tutor and governess after attending the Emma Willard School, and who was, as time soon proved, “the bravest woman I ever knew,” one of her nieces marveled. Already in place was the tall and luxuriantly bearded Upton H. Herbert, also 39, who had served as a lieutenant in the Mexican War and was a descendant of George Washington’s first patrons, the rich and powerful Fairfaxes. John Augustine Washington had recommended his friend as Mount Vernon’s first superintendent, not only because Herbert was “as familiar with everything of interest here as any other person now living” but also because of his “intelligence, information, courteous bearing, and kind manners,” coupled with “unflinching courage, steadiness of purpose and pure integrity.” Even before John Augustine moved out, Herbert set to work cleaning up the grounds and shoring up the outbuildings, and as soon as Cunningham took over, he tore down the unsalvageable veranda, built a replica, and began to make the house weatherproof.

That autumn, Cunningham’s father died, and she had to go home to run the family plantation. In December, her home state was the first to secede from the Union; in April 1861, the firing upon Fort Sumter, also in South Carolina, began the Civil War, trapping Cunningham in the South for the next six years. She extracted a promise from Upton and Tracy to watch over Mount Vernon, partly because “the presence of a lady,” she believed, would “tend to insure respect toward the place from both contending parties.” Tracy persuaded a Philadelphia friend, Mary McMakin, to come as her paid chaperone, and Herbert kept his promise not to leave his post, even though he writhed with shame at not joining his brothers and friends as a Confederate officer. A handful of freedmen stayed on as paid servants to help with the chores.

Mount Vernon’s position was truly perilous. Once the Union army took Arlington and Alexandria, four miles to the north, in May 1861, and Confederate troops gathered at Manassas, four miles to the south, the estate lay in a no-man’s-land, swarming with the robber gangs that wartime anarchy spawns. And momentous battles raged close by. “At six o’clock in the morning I was roused by the cannon,” wrote Tracy on July 22, the day after the first Battle of Bull Run, which rattled Mount Vernon’s windows with each shot, “and from then till one o’clock there was not three, no, hardly one minute between each fire. . . . The sun rose upon their fury, and went down upon their unquenched wrath. We have as yet only flying rumors, but fearful must have been the destruction of life. I never imagined anything so terrible. I could not think, could not read, could hardly pray, every sense and faculty seemed concentrated in my hearing! I tremble at the idea of those who saw their last sunrise yesterday morning.”

The indomitable Tracy decided not to leave matters solely to chance. Nine days later, she drove to Washington behind a pair of mules to ask General Winfield Scott to order his men not to harm Mount Vernon. Scott’s adjutant went into the general’s office to relay her appeal, and when he came out with the requested order, plus a pass to let Northerner Tracy cross Union lines at will, Tracy heard Scott say, as his office door closed, “God bless the ladies!” More eloquent was Scott’s order of protection: “[T]he General-in-Chief does not doubt that each and every man will approach with due reverence, and leave uninjured, not only the Tomb, but also the Home, the Groves and Walks which were so loved by the best and greatest of men.” Southerner Herbert, for his part, negotiated with the Confederates.

With her pass, Tracy made frequent trips to Washington, bringing Mount Vernon–grown vegetables and flowers to market and buying meat and tools with the proceeds. When she learned that Colonel John Augustine Washington, aide-de-camp to Robert E. Lee, had died in battle in September 1861 and that Union troops were scouring Alexandria to find and confiscate as enemy property the money the MVLA had paid him, Tracy got it from its hiding place in the house of the cofounder of the Alexandria bank—Herbert’s brother was the other cofounder—hid it, wrapped under the basketful of eggs she was bringing to market, and placed it in a safe-deposit box in the Riggs Bank in Washington for John Augustine’s heirs. Bank head George Riggs, treasurer of the MVLA, studiously looked the other way while she stowed the treasure. Then he took her eggs, paid her for them, and courteously handed back her empty basket. Later, when General George McClellan voided all civilian passes, Tracy eluded Union pickets and marched into the White House, where, she recounted, President Lincoln “received me very kindly and wrote a note to Mr. McClellan requesting him to see me and arrange the matter in the best way possible.” McClellan of course gave the extraordinary woman, whose prim, tight-lipped Victorian photograph reveals little beyond the severe perfectionism of her impeccably parted hair, a new pass.

“Mine is not the easiest task, to make both ends meet,” Tracy remarked of her sales of vegetables in Washington and little bouquets of flowers to visitors to the house, mostly soldiers, from whom she also exacted a 25-cent admission fee. “All things considered, we have got along very comfortably,” she summed up stoically. “We have been a greater part of the time between the Federal and Confederate lines, but no depredations have been committed.”

With the war over and her South Carolina affairs in order, Cunningham returned in November 1866 to take charge. Two strong-minded ladies, each now understandably feeling proprietorship over Mount Vernon, couldn’t live in the same house, it turned out—especially since Cunningham believed that “a successful and faithful private secretary” must lay “aside pro tem all individuality, that his or her mind may be but as a glass to reflect the mind of the employer”—so Tracy resigned at the start of 1868, with her companion McMakin taking over her job. Herbert agreed to stay one more year and then left, marrying Tracy in 1873—the first marriage for both 52-year-olds. They lived not far from Mount Vernon, in Burke, Virginia, where Tracy raised money to build a new Episcopal church, whose bell, cast in her native Troy shortly after her death in 1896, bears an inscription in her memory.

As regent of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, Cunningham and her handpicked board of vice regents—ladies from each of the states, “whose social position would command the confidence of the State and enable her to enlist the aid of persons of the widest influence,” she stipulated—went to work to restore the house to just as Washington had left it when he died in 1799. Cunningham herself scraped away layers of interior paint, looking for the 1799 colors, and was horrified to find that, instead of the “sweet rose” she favored for Mount Vernon’s grand New Room, “yellow—odious yellow—did reign in the ‘great room’ by order of Washington!!” So yellow it was, though she hadn’t scraped deeply enough. A much more scientific paint analysis in 1980 revealed verdigris as the original color, and an even more up-to-date microscopic pigment analysis last year revealed a more complex color scheme, with a buff dado, a rich, copper-based green on the walls with a darker verdigris trim, and a white ceiling and cove. When I saw the change this spring—with the paint just dry and almost all the original paintings and furniture back in place in perfect classical balance, including the pair of rococo candle stands that Washington had made for his wedding in 1759 and the two 1797 sideboards (one remaining of the original pair and the other, almost identical and made by the same cabinetmaker, replacing its lost mate), with the afternoon Virginia sun streaming through the grand Venetian window, as bare of curtains as the general intended, and the door open to the veranda and the majestic Potomac view outside—I gasped at the grave nobility of the great man’s vision, which struck me with the clarity of revelation, and I thought that the MVLA’s studious fidelity to it had achieved a fitting memorial indeed.

Gradually, after Cunningham retired as regent in 1875, a year before she died, the ladies recovered almost everything from the once-empty house and constantly reanalyzed the paint, changing wall colors accordingly. Vice Regent Alice Longfellow, the “grave Alice” of her father’s poem “The Children’s Hour,” found and bought Washington’s desk and returned it to his study in 1904; Vice Regent Eleanor Goldsborough, Washington’s great-great-granddaughter, donated the silver-plated plateau that Gouverneur Morris had ordered in London for President Washington’s dinner table. Less spectacular, but no less important, the ladies worked—over generations, from 1905 to 1988—to drain and buttress Mount Vernon’s riverbank, so that the entire east lawn wouldn’t slide into the Potomac, and they slid steel beams under the house to support the millions of tourists’ feet. Perhaps most amazingly, when Vice Regent and Ohio congresswoman Frances Bolton learned of plans to build an oil-tank farm on the Maryland shore opposite Mount Vernon, she personally bought the 500 acres where it would have stood and donated it in 1955 to one of the nation’s first land trusts, which she formed. Five years later, when the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission moved to seize by eminent domain a point of land directly opposite Mount Vernon for a sewage treatment plant—because, said the bureaucrats, “there is nothing there”—the congresswoman bought the surrounding land, needed to get building equipment to the site, stymieing the harebrained scheme. Thanks to the MVLA’s efforts, all this land and more now makes up the 4,000-acre Piscataway National Park that stretches six miles along the Potomac’s Maryland shore, preserving not just the general’s estate but also (except for one radio mast) the sylvan view he loved, forever.

With the publication in 1968 of the first volumes of The Papers of George Washington, a joint project with the University of Virginia that will fill 90 volumes when finished and whose first 55 volumes are already available online, the MVLA began its world-class scholarly activities, which culminated with the opening last year of the Fred W. Smith National Library at Mount Vernon. It houses many of Washington’s papers and the remaining 103 volumes of his original library (much more of it is in the Boston Athenaeum), and it hosts an active program of speeches and resident fellowships exploring Washington and the nation’s founding. The nearby Donald W. Reynolds Museum gracefully solves one of the knottiest problems of historical museums: how to interest both the serious history buff and the schoolchild. The MVLA’s intelligent answer is two museums, one for those interested in original manuscripts and the like; and another to awaken the historical imagination through a life-size model of the general on his slapping stallion, along with guns, swords, and noisy, interactive, video-game-like displays, so that the two groups will neither bore nor distract each other. With its $45 million annual budget, all of it always private except for the $7,000 that Ann Pamela Cunningham took from the federal government to make up for revenues lost during the Civil War, the indispensable MVLA runs the best-attended house museum in the nation, where it is not an overstatement to say that the spirit of Washington himself dwells.

In 1897, as the great turn-of-the-century immigration from eastern and southern Europe gathered steam, the New York Sun ran a story about how Monticello came to be saved, under the headline “A National Humiliation.” When Thomas Jefferson died broke, at age 83 in 1826, his cash-strapped family had to sell his beloved home to a stranger. But in 1834, when the house again came on the market, the story recounted, patriotic Philadelphians raised the $3,000 needed to buy the polymath third president’s architectural masterpiece and give it back to his favorite daughter, Martha Randolph. The ingenuous young man sent to make the purchase, however, got drunk on the journey and confided the story of his mission to a traveling companion on the stagecoach, who rushed to Virginia as the youth slept off his tipsiness at an inn, and bought the estate from under him. How could he do this? the distraught young man spluttered when he arrived at the Blue Ridge foothills a day late. What would the stranger take to sell the house back?

“Mein frien’ you are a glever feller, but you talk too much,” the Sun reported the wily stranger, identified as Judah Levy, as replying. “I will take a huntret tousand dollars.” Summed up the Sun: “It is a story that, if true[,] ought to bring a blush of shame to every American face.”

But almost no part of the nativist, anti-Semitic tale is true. Nevertheless, this same canard of how Monticello had fallen into “alien hands” kept reappearing into the 1950s, proving each time that no good deed goes unpunished.

Here’s what really happened.

Jefferson, who loved beautiful furnishings, rare books, and fine wine, and who spent lavishly to level his Piedmont mountaintop and build, redesign, and rebuild his beloved Monticello as his impeccable taste grew ever more refined, fell so far into debt toward the end of his life that, even after he reluctantly sold his cherished library to Congress in 1815 for $23,950, he still feared that he’d lose the house and end up without even “ground for burial.” He died before that came to pass; but because Monticello, despite all his studious efforts to farm it scientifically, had never made money, he left his heirs with $107,274 in debts, the equivalent of at least $2.6 million today.

His daughter Martha Randolph and her son Jeff, Jefferson’s executor, had no choice but to sell off the furniture and slaves in a five-day auction that brought in $47,840. Separately auctioned in Boston were Jefferson’s paintings, though only a few found buyers. While Jeff Randolph tried to sell the estate in 1828 for $70,000, no purchaser materialized, and the house, which a visitor had described as “going to decay” two years before Jefferson died, continued to deteriorate under its leaky roof and skylights. Various relatives camped out in it, and streams of sightseers carried off souvenirs, including even Jefferson’s plants and shrubs. By early 1831, Jeff Randolph dropped the asking price to $12,000 and then to $10,000, with the family retaining ownership only of the Jefferson cemetery. In August, a buyer finally appeared—druggist James Barclay, 24, who planned to turn Monticello into a silkworm farm. The price: $4,500—not much of a dent in Jefferson’s debts, which weren’t settled until 1878, three years after Jeff Randolph’s death.

The silkworm venture flopped, and the house moldered on. “The first thing that strikes you is the utter ruin and desolation of everything,” wrote the son of Jefferson’s famed architect friend Benjamin Henry Latrobe, when he visited in 1832. He came upon a broken column, its metal reinforcing rod sticking out from the top. Nearby, “somewhat mutilated,” he discovered the capital—one of his father’s designs—and piously set it back into place. A year later, Barclay gave up his quixotic venture and advertised the house for sale, along with 200 to 300 acres, in at least two newspapers. In 1834, a buyer offered the druggist $2,700 for the forlorn estate. But courtroom wrangling with the contentious purchaser over the extent of the land, which turned out to measure only 218 acres, took two years, so the deal didn’t close until April 1836.

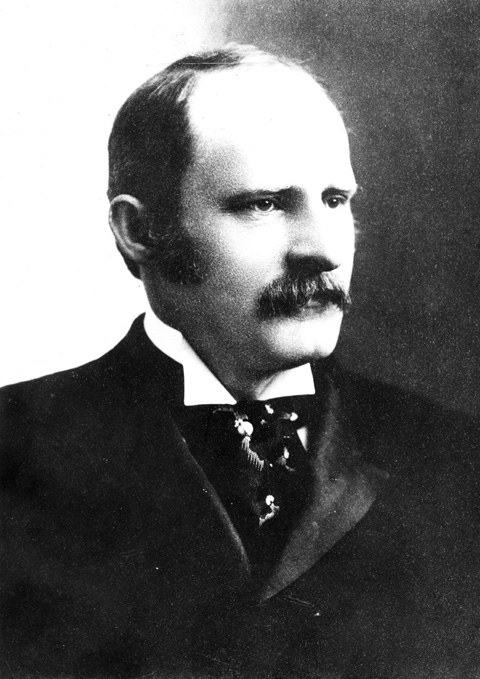

The buyer: dapperly mustachioed and dashingly uniformed U.S. Navy lieutenant Uriah Phillips Levy (who pronounced his name to rhyme with “heavy”). He was Jewish, as the Sun article reported, but he was no immigrant with an accent. Though his father had come from Germany as a child and prospered as a Philadelphia clock- and watchmaker, his mother’s family had been in the American colonies since 1733, when Levy’s great-great-grandfather, Portuguese physician Samuel Nunez, had fled to Savannah to escape the Inquisition, accompanied by a Torah that the Savannah synagogue he helped found still uses. He promptly stemmed a virulent dysentery epidemic that was raging in the Georgia town when he arrived, for which Governor Oglethorpe awarded him six farms. His daughter married the cantor of New York’s Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, and their daughter married Revolutionary War soldier Jonas Phillips. When the Constitutional Convention opened, Phillips wrote to ask the delegates, on behalf of Philadelphia’s Jews, to guarantee to all men “the natural and unalienable Right to worship almighty God according to their own Conscience and understanding.” So Uriah Levy’s reverence for the author of the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, one of the three accomplishments that Jefferson thought important enough to have carved on his tombstone, was, in a sense, an inheritance from his grandfather Phillips.

Having run away to sea as a cabin boy at ten in 1802, Uriah Levy became a sailing master and part owner of a cargo schooner by the time he was 20, when he joined the navy as a midshipman at the outbreak of the War of 1812. Patrolling the English Channel, his 18-gun brig proved adroit at seizing enemy merchantmen, capturing an astounding half-dozen on a single August day in 1813. Levy’s captain ordered him to sail one of the prizes home to port, but a Royal Navy warship recaptured the vessel, and Levy spent the rest of the war on his parole in England. Commissioned a lieutenant in 1817 and a captain in 1844, Levy displayed a curious mixture of the contentious with the compassionate in his postwar naval career. He received six courts-martial, mostly for duels provoked by anti-Semitic slurs, and he got cashiered from the service twice, only to receive presidential reinstatements. He was an early anti-flogging campaigner, both in print and on board, where he showed that he could keep perfect discipline by the mild measure of badges of shame—including, one bizarre time, the not-so-mild affixing of a few parrot feathers to the bare buttocks of a teenage sailor with a daub of hot tar, which earned Levy yet another court-martial. The navy outlawed the lash in 1850, thanks not only to Levy’s efforts but also to the shocking depictions of the practice, associated with slavery, in two bestsellers, Richard Henry Dana, Jr.’s 1840 Two Years Before the Mast and Herman Melville’s 1850 White-Jacket.

In the long stretches of leave he took during his postwar career, Levy began investing in New York real estate, with so golden a touch that by 1855, he began to appear on the annual list of Gotham’s richest men. In 1832, he went to Paris to commission a life- size bronze statue of Thomas Jefferson, whom he thought “one of the greatest men in history—author of the Declaration of Independence and an absolute democrat,” who “did much to mold our Republic in a form in which a man’s religion does not make him ineligible for political or government life.” He hired a then-famous sculptor, Jean David d’Angers, and called on the Marquis de Lafayette, 75, asking to borrow a portrait of Jefferson to serve as a model. Gladly lending him the Thomas Sully painting that he owned, Lafayette asked Levy what had ever happened to his dear friend’s Piedmont home, which he remembered visiting with still-vivid pleasure. Levy promised to find out; and, after presenting his Jefferson statue to Congress (it now stands in the Capitol Rotunda), he fulfilled his promise to check on Monticello—and ended up buying it.

He contemplated going one step further. “Captain Levi is hear ‘raving for a wife,’ ” wrote Virginia Trist, one of Jefferson’s granddaughters, after the 42-year-old bachelor paid her a visit in Washington in the midst of purchasing Monticello. “He has talked in a way to make [me] think that he wishes a grand-daughter of Mr. Jefferson to go and share the comforts of his charming home with him.” Indeed, she wrote, “he was told that to make him a complete Jeffersonian he should marry a descendant of Thomas Jefferson.” Any of the unmarried granddaughters, ranging from 22 to 34, would do. “I think the Captain is willing to leave it to be decided in a family council which of the three is to be Mrs. Levi,” reported Trist to her husband. But nothing came of the notion, though Levy stayed on friendly terms with Jefferson’s descendants for many years, as Marc Leepson reports in his invaluable account of the Levy family’s 89-year tenure at Monticello, Saving Monticello.

Visitors soon reported that Monticello was again in good repair, thanks to the Levy fortune, and everyone noted the beautifully polished state of Jefferson’s elaborately inlaid floors. Of the president’s original furnishings, nothing remained but his bust of Voltaire, his huge mirrors, and the great clock over Monticello’s front door and the ladder needed to wind it, though the clockworks were clogged and corroded, so the ladder hadn’t seen duty in a long time. The terrace walkways on either side of the house had collapsed before Jefferson died, and they still weren’t repaired, though Levy had added about 1,000 additional acres to the 218 that he’d bought with the house. When not cruising on the ship he commanded, the Vandalia, the captain himself mostly lived in New York, visiting Monticello as a vacation house. He brought his 68-year-old mother and an unmarried sister with him in the spring of 1837; two years later, when he was away patrolling the Gulf of Mexico in the Vandalia, his mother died and was buried in Monticello’s cemetery.

As Levy aged, his hair growing gray and his girth thickening under his fashionably cut uniforms from love of good food and fine port, two great changes affecting Monticello’s fate occurred. First, the husband of Levy’s 18-year-old niece died childless, and the 61-year-old Levy, who had always liked the ladies but never married one, followed the custom set by the biblical Ruth and her dead husband’s much older kinsman Boaz, and married the exotically beautiful and flirtatious teenager, Virginia Lopez, in 1853. Ruth and Boaz became the great-grandparents of King David; but Levy, though he dyed his hair and mustaches black and took his young wife cruising the Mediterranean on his then-command, the Macedonia, produced no offspring. Second, the Civil War broke out in 1861, sending Levy to Washington to run, ironically, the court-martial board. There he fell ill, returned to New York, and died in 1862.

The consequences of these two events: first, the Confederacy seized Monticello as enemy property and sold it to Virginia colonel Benjamin Ficklin, the man who conceived the Pony Express. Second, after the Civil War, the property reverted to the heirs of Uriah Levy. Levy’s will had left the estate to the people of the United States—or, if the federal government refused the gift, to the citizens of Virginia—to use as a school for the orphans of naval warrant officers. But the New York Supreme Court invalidated the will in 1863, and the Richmond, Virginia, court followed suit five years later, ordering the estate sold and the proceeds distributed among Levy’s heirs. But who were they? His widow, now 27 and remarried? His brothers and sisters, nieces and nephews? Each of them thought him or herself the rightful owner of Monticello, and lawsuits raged among them for more than a decade. With the title still contested, Uriah Levy’s nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy, just graduated from NYU Law School at age 21, began to buy up his relatives’ claims to the estate in 1875, and by 1877, he owned half of it. He had bought out most of the rest by the time Monticello finally went up for auction in February 1879, so when he won it and the original 218 acres with the auction’s sole bid of $10,050, he had essentially bought Monticello from himself.

What had happened to the house in the meantime was what happens to any property tied up in litigation: it fell once more into a Dickensian state of ruin. As the suits dragged on, Uriah Levy’s old overseer, Joel Wheeler, “took care” of Monticello and sometimes lived in it. While he grew increasingly blind, paint peeled, glass broke, shutters and gutters disappeared, grime deepened, and the roof and terraces rotted. Wheeler dug up the lawn for a vegetable garden on one side and a pigpen on the other. Cattle wintered in the cellars, and Wheeler winnowed grain on the parlor’s parquet floor. On his watch, judged Wheeler’s successor, Thomas Rhodes, Monticello “was wantonly desecrated.”

With his piercing eyes, square, determined chin, magnificent mustache, high forehead set off by receding hair, massive pearl stickpin, and fine Havana cigars, Jefferson Levy, “well over six feet tall, well built and Bond Street tailored,” a friend reported, had all the money and grit needed to put the estate right. Like his uncle, he had become a New York real-estate investor (at 17), and, after law school, he turned to stock speculation as well, so that by the turn of the century, he, too, had made himself one of New York’s richest men. He repaired and renovated, replaced Jefferson’s elaborately complex roof, and made only minimal and readily reversible changes to the great architect-president’s design. He also added to the land, bringing its total up to 663 acres. When the 79-year-old Virginia Trist, the Jefferson granddaughter whom Uriah Levy had sounded out about marrying one of her sisters almost half a century earlier, visited Monticello in 1880, she expressed pleasure in how much Jefferson Levy had done “in the way of cleaning both house & grounds. . . . [It] is so gratifying to see the beloved old place in the hands of a person who appreciates it, and whose wish appears to be to restore the whole house to its former condition.”

Though Levy imagined that he was filling the house with Jeffersonian furnishings, the truth is that, except for Jefferson’s coffee urn and music stand, he bought gilded-age plutocrat’s furniture from Sloan’s in New York, French pieces whose “royal descent is well attested,” reported one visitor, so that anyone “who knows his France feels that he is in a miniature Fontainebleau.” In the hall, across an elaborate table that Napoleon had given to his doctor, a full-length portrait of Jefferson faced a full-length portrait of Uriah Levy, in due course replaced by one of Jefferson Levy, who’d been elected to Congress in 1898 as a conservative Democrat from upper Manhattan; in the gold-brocade-draped parlor, in which ticked a clock from Louis XV’s palace, a gilt-and-glass cabinet displayed such relics as Uriah Levy’s epaulettes and a lock of Jefferson’s hair.

The implied equivalence between Jefferson and the Levy family didn’t sit well with Texas-born Maud Littleton, who visited Monticello in April 1909 with her husband, Martin, the ex-D.A. both of Dallas and of Brooklyn, and an ex-Brooklyn borough president, now making his fortune as a hotshot trial lawyer (famously defending the millionaire murderer of architectural genius Stanford White), before getting elected to Congress from eastern Long Island in 1910. “I did not get the feeling of being in the house Thomas Jefferson built and loved and made sacred and of paying a tribute to him,” complained Maud Littleton. “Somebody else was taking his place in Monticello—an outsider. A rank outsider.” Following up on a suggestion that William Jennings Bryan had made in 1897, just after his loss of the presidential election to William McKinley, that Levy should sell Monticello to the federal government, Mrs. Littleton published a pamphlet called One Wish in August 1909, under the pseudonym “Peggy O’Brien.” Jefferson, she wrote, “is not one man’s man. He belongs to the people who love him. . . . And their one wish is to be free to lay upon his grave a Nation’s tears. It is my one wish, too.” What’s more, it was Uriah Levy’s wish, she added, expressed in his “wonderful will,” framed “to secure Monticello to the people of the United States.”

So she threw herself with boundless zeal into a crusade to take away, in the name of patriotism, a house that its owner didn’t want to sell, launching a national movement to raise money and gain support, which the New York Herald described in a breathless Page One story. Her East 57th Street house “is the busiest place imaginable,” the paper reported. “It has all the appearance of the national headquarters of a political organization. The furniture in the dining room has been taken out and a dozen stenographers take dictation and work eight hours a day at typewriters,” with Mrs. Littleton directing everything from “a desk at the centre of a richly furnished room . . . littered with papers and mail of all description.”

It didn’t hurt that she had a rich husband, now in Congress. “My husband has been a perfect angel to me in this fight,” Littleton said. “He has never denied me a penny I asked.” He also clearly swung his political weight on her behalf, for in March 1912, a senator introduced a resolution to appropriate funds to buy Monticello, and the next month the House introduced One Wish into the Congressional Record. In June, the House began committee hearings on the purchase, with Maud Littleton, of course, giving testimony, complaining—falsely—that Levy neglected and restricted access to Jefferson’s grave and characterizing the rich life he lived in the sybaritic third president’s house as “grotesque.” In July, she testified before a Senate committee, repeating in lurid detail the Sun’s libel about the Levy family having stolen Monticello out from under those aiming to buy it back for Martha Jefferson Randolph. In further testimony before the House in August, Littleton ended her plea for the government to buy Monticello by bursting into tears.

“Is this the way women are to plead for what they want?” jeered a suffragette in the Washington Post. Far better to emulate those who, “unlike Mrs. Littleton, did not weep in battle for their causes: Clara Barton, Florence Nightingale, Jane Addams, Catherine de Medici, and Mary Queen of Scots.” As a clearly non-suffragette Virginia paper acidly editorialized, the “agitation gives Mrs. Littleton something to do, which she can do brilliantly, and it draws upon her the attention of the nation, which she seems to enjoy with great complacency. Perhaps it’s more fascinating than bridge.”

For their part, the Jefferson family rejected Littleton’s accusations against Levy and objected to her enterprise. The family, wrote one of Jefferson’s great-great-grandsons to Levy, “has always had a feeling of obligation to you for the restoration and good care” of the house. “We view with surprise the attempt to dispossess you against your will of property which belongs to you. Certainly the former owner of Monticello would never have believed such a thing possible in our country.” Littleton’s campaign, another great-great-grandson wrote, “is a travesty of justice, a direct infringement on American liberty, and directly opposed to the principles and sentiments of the great builder of Monticello.” In December 1912, the full House voted down the resolution to consider buying the estate.

But Mrs. Littleton would no more take no for an answer from Congress than from Levy. With public support from dignitaries ranging from tycoon J. P. Morgan to union organizer Samuel Gompers, she managed to spark a new set of hearings in March 1914 before a Senate committee that agreed to put the question of federal purchase of Monticello before the full body. The House declared itself ready to back up a favorable decision.

Meanwhile, three events—only two of them public—began to change Jefferson Levy’s mind. First was a scurrilously anti-Levy article, “Monticello: Shrine or Bachelor’s Hall?,” in the April 1914 issue of Good Housekeeping by its star columnist, Dorothy Dix, then as much a household name as the magazine itself once was. With anti-Semitic digs against the Levys as “aliens,” Dix trotted out the canard of how the family “stole” Monticello from—in her telling—a “young relative of the Jeffersons.” Ever since, Dix falsely asserted, no one may visit Jefferson’s grave “except by special permission of Mr. Levy.” Worse, “unless some action is taken, all the marks that Jefferson set upon Monticello will be swept away.” The “house is decaying, and the little graveyard is overgrown with weeds.” Echoing a threat that a Senate bully had made in an earlier hearing that, since the government has the power to take private property by eminent domain, “if the Government of the United States wants Monticello, it can take it,” Dix observed more mildly that eminent domain was perfectly just in “exceptional circumstances when the right of one individual should give way to the good of the many.”

The power of a report in a leading media outlet is independent of its truth, of course; yet Mrs. Littleton had a still-mightier oracle. “It is only a matter of weeks before the American people will own the deed,” she announced. “Astrologists have so advised me.”

Second, in September 1914, William Jennings Bryan renewed the plea he had made in 1897 that Levy sell Monticello to the nation, but now he made it in his capacity as Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state to a loyal Democratic congressman who, though he didn’t share Wilson’s utterly anti-Jeffersonian passion for big government, was nevertheless thinking of running for the Senate. “Mr. Bryan’s letter makes it an administrative movement,” Levy mused. “I will treat the idea more seriously than ever.” So much so that in October, Bryan announced that Levy had written to him, offering to sell Monticello to the federal government for $500,000. Five days earlier, however, Levy, having decided against a Senate run, had lost the primary for his House seat.

The third reason for his change of mind was known only to Levy himself—who, as much as he loved Monticello, also loved his New York life, in which he regularly met his fellow magnates at dinners at the Waldorf, “to discuss not only operations in Wall Street,” the Washington Herald reported, “but to tell each other how the government really ought to be run down in Washington.” But the truth is, he was going broke—and he ended up almost as broke as Thomas Jefferson himself. Congress dithered over whether to accept his offer and dickered over his price until the end of 1917, without coming to a decision. In 1919, wracked by wartime stock-market losses and having sold most of his other real estate, Levy put Monticello on the market. He needed cash.

In February 1923, a group of high-powered New York lawyers, including Virginia-born Stuart Gibboney, convened a dinner at the Vanderbilt Hotel of Monticello enthusiasts, including representatives of such groups as Littleton’s that had tried and failed to raise money to buy the house, to plan the next step. A follow-up lunch in March brought forth the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, which struggled hard for the rest of the year to raise the $100,000 down payment, delivered to Levy on December 1. He turned over the deed to the estate and burst into tears. Three months later, he was dead of a heart attack at his East 37th Street house. He was 71 and insolvent. The $1 million he owed his broker was only the largest of his debts.

The foundation, with Gibboney as its president, had more to restore than just the house, though University of Virginia architectural historian Fiske Kimball spent the next three decades bringing Monticello and its furnishings and gardens back to their 1809 condition—the year when Jefferson finally believed he had finished his project, to the extent he could ever be finished with something. But Jefferson’s reputation, unlike Washington’s, also needed some refurbishing, since in the 1920s no current book on the third president was in print, and one of the organization’s founders recalls the surprise with which used-book sellers greeted his request for tomes on Jefferson. So the foundation set out to educate Americans, seemingly with as short memories then as now, about the author of the Declaration of Independence. With rapid success: Franklin Roosevelt spoke at Monticello in 1936 and dedicated the Jefferson Memorial in Washington in 1943. Jefferson biographies began to gush from the presses in the 1930s and 1940s, along with the first volumes of the definitive edition of Jefferson’s papers. Today, a brand-new visitor center and an International Center for Jefferson Studies flank Monticello, and the third president’s reputation now stands so high that the foundation feels free to examine some of the shadows as well as the highlights of his career: under the 24-year presidency of the genial Daniel Jordan, Monticello became, among other things, a center for the study of slavery, too.

It’s a natural progression for an organization that began its ownership of Monticello by desegregating its restrooms and hauling down the Confederate flag on its grounds. And one of the first things that the now-retired Jordan did when he became the foundation’s head was to erect a plaque at Uriah Levy’s mother’s grave, acknowledging, after 40 years of silent neglect, the Levy family’s indispensable role in saving Monticello.