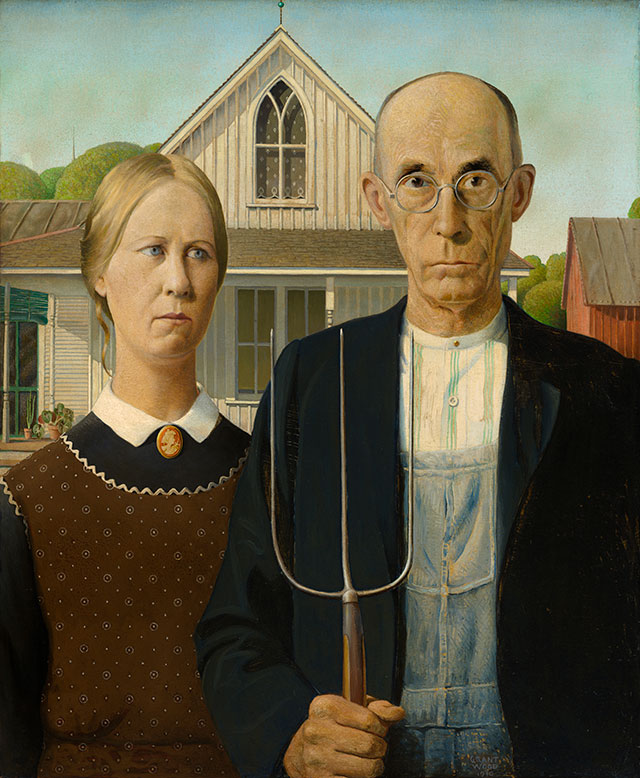

Grant Wood (1891-1942) was the least likely of overnight sensations. In 1930, he was an unknown, middle-aged interior decorator and painter living in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, when his submission to the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual juried art show won a bronze medal and $300. Wood was delighted. He hired a press agent—during the Depression, you could hire someone to do anything on the cheap—and within days, American Gothic appeared on the front page of the arts section of the Chicago Evening Post. The paper’s art critic called it “the biggest kick of the show” and truly “American.” Soon reproduced in hundreds of publications, American Gothic joined Whistler’s portrait of his mother as one of the best-known American paintings.

“American Gothic and Other Fables,” the Whitney Museum of American Art’s survey of Wood’s career is a surprising, gratifying, and essential show, which includes the famed image. Wood pieced together enough education as a young man to design and sell jewelry and silverware, paint murals for schools and businesses, and teach art. In the 1920s, he went to Europe four times. We don’t know much about his travels except that he went to Paris, Belgium, Germany, and Italy, didn’t socialize with American avant-garde artists, and developed “Latin Quarter manners” that offended people when he came home—but come home he always did. Even after American Gothic, and after Time called him “chief philosopher and greatest teacher of representational U.S. art,” he stayed in Cedar Rapids, taught at the University of Iowa, and lunched at a local diner each day. He was self-sufficient and frugal. He was never poor. He built his own house and furniture. Sometimes he lived with his mother and sister. He was briefly married. Until he died, he occupied a peculiarly American niche: an eccentric local arts celebrity, a strange and familiar presence, most likely gay, never feared, “one of us,” but what I would call a pet outsider. He saw things others didn’t, felt free to express what many wouldn’t, found merit in what snobs derided, and noticed qualities some took for granted.

Along with fellow Midwesterners Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, Wood was an anchor figure in a national art movement called Regionalism. They claimed to disdain foreign, notably French, influence; celebrated American values like decency, stoicism, and independence; promoted local training; and professed that good art needn’t come only from New York. Wood thought that one criterion of good art was scrutability; that everyone could, with effort, understand it.

What does American Gothic mean? Wood initially said that the picture was about the architecture. It’s true that the picture started with the house. Wood thought an Iowa façade style descended from French cathedrals was pretentious. He added the figures after he decided on the house as a subject. He sometimes said that he depicted a married couple, sometimes a father and daughter. The easily recognizable models were his sister, Nan, and his dentist. He later said that he invested the figures with “fanaticism and bad taste” but that they were “basically good and solid people.” He looked for “severely straight-laced characters” who would reflect the house’s exterior. He certainly succeeded. Lots of Cedar Rapids residents thought that the painting mocked Iowans for their piety and austerity. Is it about repression? Incest? Hopelessness or melancholy? Mourning? Critics have offered these and other interpretations over the years, but the work doesn’t provide a simple answer.

The show’s curator, Barbara Haskell, decided to display American Gothic without fanfare, beside other paintings—mostly single-figure works that aren’t portraits but storytelling types. Wood said that the painting “begins with Mencken,” referring to H.L. Mencken’s relentless condemnation of culture in the Bible Belt, a term he coined. Carl Van Vechten’s 1924 satirical novel, The Tattooed Countess, was set in a fictionalized Cedar Rapids, once his hometown. Sinclair Lewis, Theodore Dreiser, and Sherwood Anderson were among the legion of writers who skewered the Midwest as a wasteland drained of sophisticated feeling, on the one hand, and a swamp of barely repressed weirdness, on the other. The less you know of small-town life, the more compelling such mean-spirited generalizations seem. Wood’s take is kinder and gentler, as were Booth Tarkington’s and Willa Cather’s, but we need his other work to understand why.

In American Gothic, Wood parodies people everyone who has lived in a small town knows—and few really like. They’re tight asses, so much so that they’re funny, as Mark Twain is often funny. Plaid Sweater, from 1931, is another imaginary portrait. The subject is hearty, wholesome, purposeful, reliable, and also dapper. We can see the admirable man in the boy. Victorian Survival, also from 1931, is lovely. Stereotype and satire can quickly elide into adoration. The modern phone by the woman’s side isn’t a parody; it can only imitate her. It can’t supplant her dignity and, as the title suggests, her durability. She also offers a new take on the elegance of the basic black dress.

Wood was a skeptic. Big ideas made him wary. Daughters of Revolution is a delicious picture in this respect. It depicts three old ladies standing in front of Leutze’s iconic Washington Crossing the Delaware. They’re smug and prim. Their big idea—that descent from Revolutionary War figures confers special wisdom, refinement, and stature—is a joke, but it’s only a poke in the ribs. The painting is beautifully designed, with soothing ripples and patterns. The women are self-important but also serious and direct. They’re ever so soft and yielding, as are most grandmothers; they’re not evil. Even revolutions need keepers of standards.

By the late 1930s, some linked Regionalism with yahooism, then isolationalism, and later fascism. At the University of Iowa, Wood quarreled with colleagues over teaching methods. The battle became politically freighted but sounds tiresome and juvenile today. In 1941, the new department chairman tried to fire Wood, insinuating that he was a “communazi” because he produced art that appealed to a broad public. This populism, it was feared, invested an artist with the power to rile people for the wrong reasons, and it took away from specialists the keys to the locked door of meaning and judgments of quality.

A parallel school of regional artists worked in New England and included Norman Rockwell and Grandma Moses, along with writers like Robert Frost. American Gothic in 1930 and Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, which opened in 1938, bookend the 1930s, and have a certain amount in common. Wilder was a visionary while Wood was quirky and idiosyncratic but both works are enigmatic, small-town tales. Both seek in modest things the real, the timeless, and the essential. One artist found them in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the other in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire.

The Whitney catalogue includes a fascinating biographical chapter that gives Wood an articulate, subtle voice as he bobs and weaves when critics try to pry meaning from him. Wood got buried in both scholarship and the marketplace until Wanda Corn resurrected him in her 1983 retrospective. Knowing Wood’s story is useful in appreciating his work, which otherwise can feel isolated from his wry personality.

Painting after 1945, led by Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Franz Kline, and others, emphasized abstraction and emanated from New York, leaving no room for figures like Wood. A telling story: while Wood’s detractors were trying to fire him at the University of Iowa, the painter and his supporters were trying to jettison the young H.W. Janson, a junior professor in the art history department. Janson’s crime: promoting Picasso as the age’s leading art genius. Janson’s earliest book, published in 1962, featured as many Picassos as it did Michelangelos, and virtually ignores American art. Wood, of course, thought Picasso was a charlatan, as did Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins, among others. Janson would later become famous, though, for his ubiquitous Western art tomes, printed by the millions and used in most introductory college art history surveys. Wood might have had the last word.

All pictures courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art