New York City is in the throes of a deadly heroin epidemic cutting across boundaries of race and class. The death toll from overdoses now outpaces that from homicides. On Staten Island alone, overdose-related fatalities are on course to double this year over last.

The city’s dedication to the principle of “harm reduction,” which dominates human-services training and practice throughout much of the West today, hasn’t helped. The provision of Naloxone, an opioid antagonist that can quickly reverse an overdose, to 20,000 NYPD officers has been lauded as a lifesaver. Dozens of lives have indeed been saved through application of Naloxone, but once a drug user has been revived this way, he can’t be arrested or otherwise forced into treatment because the threat of such intervention would be likely to dissuade users or their associates from calling for help in the first place. So the overdoser is treated like any accident victim and left to his own devices once his condition stabilizes. (The pop singer Prince was reportedly revived with Naloxone a few days before his fatal overdose.) Thus, harm reduction—whether intentionally or not—normalizes the underlying behavior, minimizes the psychological shock of overdose, and perhaps makes it easier for addicts to keep using.

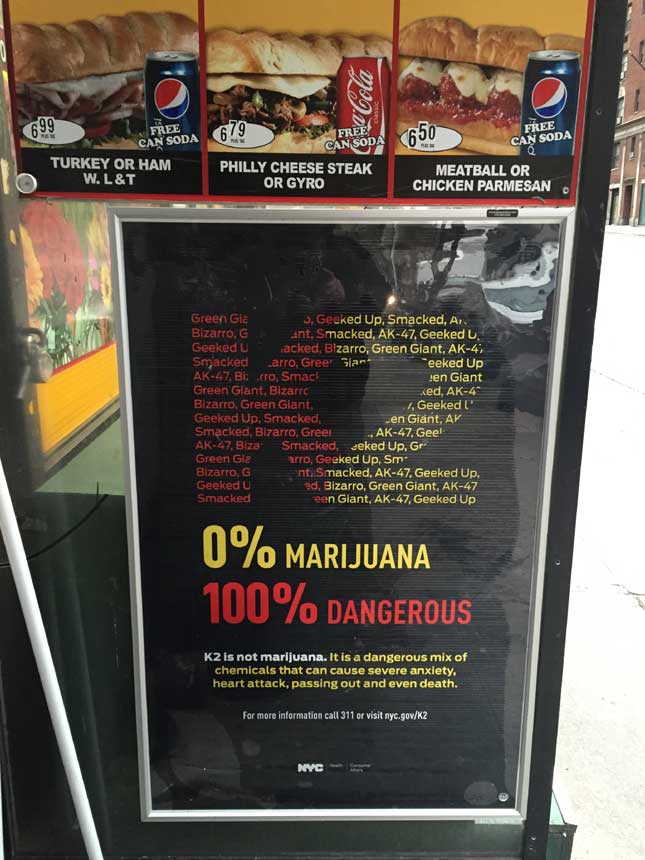

The harm-reduction approach makes too many concessions to supposedly ordinary drug usage. New York City recently initiated a major campaign to stop the use of so-called synthetic marijuana, which, known variously as “K2” or “spice,” consists of herbs that have been sprayed with psychoactive chemicals. Sold in delis for five dollars a hit, spice quickly became a major scourge, resulting in hundreds of hospital admissions, many cases of psychosis, and even some deaths. The city acted quickly to outlaw the supply, which resulted in a significant decline in usage. To counter demand, the Department of Health invested in a widespread advertising campaign, with dramatic placards reading “K2: 0% Marijuana; 100% Dangerous.” Yes, K2 is dangerous, and no, it isn’t marijuana. But the implication that if it were marijuana, it wouldn’t be dangerous seems an imprudent position for city government to take. After all, marijuana has been linked to schizophrenia in young users—it’s hardly a perfectly safe alternative.

Taking an even less subtle approach, a city-funded group called New York Harm Reduction Educators offers a “drop-in space” and hands out a leaflet, “Healthier Tips for Smoking Crack,” which includes useful suggestions such as, “Decide how much you’re going to use before you start” and “Buy from a dealer you trust.” The problem with the harm-reduction approach here is that smoking crack is, by any understanding, an extremely harmful activity. If the average crack addict were a parsimonious Ben Franklin–type, he might find it wise and commonsensical to “smoke at times that will allow you to rest and be sober in time for work.” But such users are mostly a liberal fantasy. There are no elderly crack addicts. Drug addiction consumes lives.

Worse still, under the banner of harm reduction, the city council recently proposed that New York establish “drug-injection sites,” where addicts could bring their drugs to inject “under medical supervision.” To his credit, Mayor Bill de Blasio wouldn’t approve funding for this measure, rejecting it as not “appropriate.” But the impulse to normalize destructive, deviant behavior in the name of saving lives and reducing hardship remains popular. No easy solutions exist to the social misery of drug addiction, but surely we can devise a humane approach short of utter surrender.

Photo by Mark_Hubskyi/iStock