The overregulation of American housing markets began in the nation’s coastal, educated, productive enclaves. Over time, however, barriers to building have spread. Tony suburbs of Phoenix and Austin, which once left their builders free to construct plentiful affordable housing, have now become almost as restrictive as the Boston area.

The expansion of land-use regulations will have an enduring impact on the cost of American housing. The web of restrictions pushes prices up by limiting the number of houses that can be built and deters development through the uncertainty that it creates. Since the permitting process often allows only tiny one-off projects, American builders can’t exploit the economies of scale that have made almost every other manufactured good far more affordable.

The consequences of land-use regulations go beyond high housing costs. Since people can’t afford to move into areas that don’t build, America’s most productive places have remained too small. The nation’s gross domestic product is therefore lower than it could be with a more rational housing system, and poverty too often gets frozen. Housing-price bubbles are more extreme when the housing stock is fixed, too, so the country courts financial chaos by refusing to make building easier.

Unfortunately, the cyclical nature of the housing market makes reform difficult. Americans are taking another ride on the housing-price roller coaster at this moment—as the Federal Reserve hikes interest rates to reduce inflation, prices will probably continue to fall. Reformers can generate momentum for change when prices are rising, but that momentum stalls when prices crash. There was little popular enthusiasm for promoting housing affordability in 2008, as housing prices collapsed during the financial crisis, and there won’t be any in 2024, either, if rising interest rates push housing prices substantially down.

The needed changes won’t get anywhere this way. Every major reform effort in the U.S. has taken time; if we let the whipsaw of the housing cycle determine when we care about the issue, we will lose the opportunity to create a more productive, more flexible, and more open America. The only chance for real housing reform is a sustained national and state effort to give more Americans the freedom to build.

From 2012 to 2022, America experienced another of its great housing booms, almost as big as the one that occurred from 1996 to 2006. Between June 1996 and June 2006, housing prices rose 122 percent, or 72 percent, correcting for inflation, according to the Case-Shiller national housing-price index. According to the same data source, American housing prices increased 115 percent, or 67 percent in real terms, between June 2012 and June 2022. The demand for housing soared particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic: nominal housing prices rose 45 percent between February 2020 and June 2022, and real prices went up 26 percent.

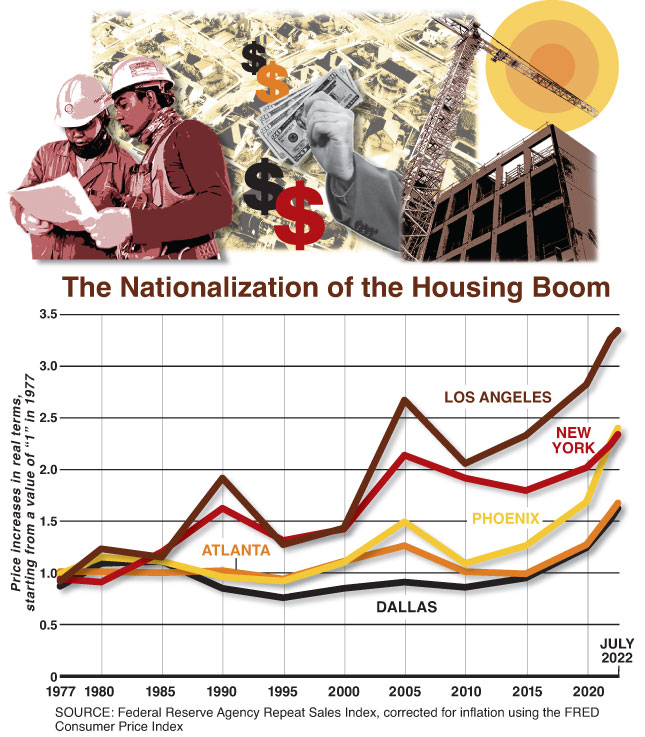

It’s surprising that the 2012–22 boom is comparable with the 1996–2006 one, since that earlier cycle was more extreme than any other residential housing-price event in American history. The similarity of the nationwide numbers, though, hides an important difference. The earlier boom was concentrated in a smaller number of metropolitan areas. Our recent boom has extended nationwide, affecting a wider swath of cities. Indeed, the trend is for each new housing boom to affect more metropolitan areas, partially because building regulations have become ubiquitous.

The figure above shows the nationalization of the housing boom, as seen in the stories of five metropolitan areas. These data come from the repeat-sales indices of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, corrected for inflation. Each series takes on a value of one in the fourth quarter of 1977, when Phoenix enters the sample.

The series shows three booms. In the first, during the late 1980s, only New York City and Los Angeles see prices jump. In the second, in the 2000s, Los Angeles, New York, and Phoenix experience exploding prices. In the last boom, of the 2010s, Atlanta and Dallas join the party, and all five cities see significant price increases.

Atlanta’s 46 percent real-price growth between the end of 2017 and the third quarter of 2022 is worth noting because that city had previously been the textbook case of how cities with abundant housing supply go through milder price swings—that is, they don’t have as severe boom–bust cycles as places that restrict housing construction. In a 2018 paper that I coauthored with Joseph Gyourko, we juxtaposed the experience of Atlanta and San Francisco, which tightly limits housing development, over the period from 1985 to 2013. San Francisco’s prices swung wildly up and down, while its level of permitting for new housing stayed flat and minimal. Atlanta’s prices stayed flat, while its permits gyrated. But more recently, Atlanta’s prices have rocketed ever upward, just like those in coastal California.

In an earlier work that I coauthored with Gyourko and Albert Saiz, we split America’s housing markets into thirds, based on the ease of building. During the 1996–2006 boom, the most restricted third had average real-price growth of 98 percent, while price growth averaged just 28 percent in the least regulated third.

When a functioning market supplies a good elastically, you don’t get bubbles. Consider an ordinary product: the trash can. These are extremely useful items, of course, but there has never been a trash-can bubble, where the market price of trash cans exploded, say, by 300 percent. The world’s producers can make trash cans almost anywhere and out of almost anything. Elastic supply ensures that prices never get out of whack.

When the housing market works correctly, housing becomes just another good that is relatively easy to build, and low construction costs hold prices down. But when housing supply gets restricted, prices inflate and bubbles become far more common. One of the downsides of having more cities with highly regulated housing markets is that we can expect more of them to go through housing-price booms and busts, with the resulting financial pain.

Easy permitting policies do reduce extreme housing-price cycles, but it is also possible for buyers to lose their heads, for a short period, even in zoning-permissive places. In 2005 and 2006, for example, buyers bid up prices in Las Vegas and Phoenix at the same time that builders were bringing a torrent of new housing onto the market. The result was a predictable mega-bust. The Phoenix metropolitan area permitted more housing in 2021 than it did in 2006, so perhaps history will repeat itself. But in Atlanta, permitting for new housing fell by 42 percent between 2006 and 2021, so permanent price increases seem more likely in that city.

The laws of supply and demand aren’t going away. If demand to live in a city is robust and supply is limited, prices will rise. The figure above shows real rents and housing prices in Los Angeles over the last 70 years.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when L.A. was much smaller, the city was producing far more housing. Over the last 60 years, housing production has declined, and real housing rents have risen dramatically. These housing trends are not quite as sharp as in New York City, where the fall in permits and the rise in prices are both more extreme, but they are significant.

Most of California remained affordable in the 1970s because California had been a builder’s paradise. Starting in the 1960s, a new set of rules, often environmental in justification, came into play, making construction much harder. In fact, restricting building in coastal California is the last thing that environmentalists should want if they care about reducing global emissions. My work with Matthew Kahn catalogs carbon emissions associated with living in various parts of America and shows that building in naturally temperate coastal California rather than, say, outside of sweltering Houston or Phoenix, will result in less emitted carbon overall, as people use air conditioning less. Nevertheless, policymakers cite environmental justifications for rules that restrict building in California—and send prices soaring.

My coauthors Gyourko and Saiz, as well as their coauthors Jonathan Hartley, Jacob Krimmel, and Anita Summers, have measured the level of building regulation across America. They survey people involved in the planning process about all the ways that construction can be made harder, from explicit exactions on developers to long approval times to the involvement of courts and state legislatures. They combine these questions into an overall index that ranks community and metropolitan areas ranging from San Francisco (the most restrictive) to St. Louis (the least). Some 75 percent of the land in the San Francisco region and 68 percent in the New York area lies within a community considered “highly regulated” (defined as being among the 25 percent most regulated communities in the U.S.). Unsurprisingly, this measure correlates strongly with housing prices and is closely linked with the value of a quarter-acre lot that comes with the right to build a house.

They sent out the same questions in 2006 and 2018, so they can compare the changes in America’s regulatory landscape over time. Their first key finding is that efforts to reduce regulation in constrained places like New York and Los Angeles have largely failed: “At the metropolitan area level, there is no case of a highly regulated market as of 2006 becoming substantially less regulated over time.” Further, the path of regulation seems to follow a pattern of spatial contagion, spreading both within and across regions. Ninety percent of metropolitan areas that started out strict in the survey increased “the share of their communities that themselves are highly regulated.”

While the coasts were the initial epicenters of overregulation, 61 percent of the non-coastal West and 53 percent of the non-coastal East became substantially more regulated between 2006 and 2018. By contrast, 34 percent of the non-coastal East and 28 percent of the non-coastal West reduced regulation; 52 percent of the Sunbelt became more regulated, and 33 percent less regulated. Living up to West Virginia’s state motto, Montani Semper Liberi, the U.S. mountain region was the only one in the country with more places cutting regulation than increasing it.

Across the country, the biggest regulatory changes were seen in minimum lot sizes and the number of entities required to approve any rezoning. In 2006, 28 percent of communities had a minimum lot size of one acre. By 2018, 39 percent of communities in the sample had a minimum lot size greater than one acre. The share of communities where a rezoning required approval by at least three entities went from 22 percent to 45 percent.

This creep of regulation means that restrictive zoning is no longer just a problem for New York and San Francisco. Regulatory curbs on new building are now part of life around much of the United States, and that has pernicious effects that go far beyond just pushing up prices.

This closing of the metropolitan frontier has macroeconomic implications. Again, restricting the supply of something that is in demand will make asset bubbles far more likely—and these, if large enough, can have a massive destructive impact when they burst, as they did in 2007. When housing prices went into free fall, the U.S. financial system broke down, which unleashed worldwide economic chaos. (If housing prices fall dramatically in the next two years, we can hope that the reforms following the last housing crash have at least made our banks more resilient.)

The second macroeconomic point is that restricting housing growth means limiting the movement of poor people to rich, productive places. Throughout our history, Americans have moved in search of economic opportunity. In the nineteenth century, farmers left the rocky soil of New England for the richer ground of the Ohio River Valley. In the twentieth century, migrants fled the Dust Bowl for California and the Jim Crow South for Chicago and Detroit. That process of relocation has slowed greatly because poor people cannot buy or rent homes in the prosperous areas of technological progress, such as Silicon Valley.

“By making America poorer, restrictive zoning limits the tax revenues that could fund national defense or care for the needy.”

Economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag document the disappearance of directed migration. Between 1940 and 1960, the populations of rich states grew much more than the populations of poor states because the poor moved in large numbers to rich places. Between 1990 and 2010, on the other hand, population growth was faster in poorer states because rich places made building so difficult.

Silicon Valley was wealthy even 50 years ago, and its wealthy residents did what Mancur Olson told us to expect them to do in his classic The Rise and Decline of Nations: they organized to protect themselves from outsiders. They made building increasingly tough, which ensured that their homes became vastly more valuable. These high housing costs then meant that only the most able outsiders could afford to come.

The flip side of this situation can be seen in America’s eastern heartland. In a great stretch of America, running from Louisiana and Mississippi through Appalachia and up to the cities of the Rustbelt, wages remain low and mortality has risen. In many counties within this broad region, more than 25 percent of prime-age men are not working, and often have not worked for a long time. Why don’t they move to San Francisco? More than one-third of these prime-age nonworking men in the eastern heartland are still living in their parents’ homes. Others are living in a home owned or rented by someone else. They obviously can’t afford to pay for housing in San Francisco, and their parents aren’t going to give them a spare room there, either. Consequently, limited housing keeps them trapped in places with few prospects.

The economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti have tried to estimate the total lost gross domestic product “because high productivity cities like New York and San Francisco Bay area have adopted stringent restrictions to new housing supply, effectively limiting the number of workers who have access to such high productivity.” They find that “these constraints lowered aggregate US growth by 36 percent between 1964 and 2009.”

Their estimate is debatable, but it is surely true that America is impoverished when productive places artificially constrain growth with housing regulations. This should make local housing regulations a matter of national concern. By making America poorer, restrictive zoning limits the tax revenues that could fund national defense or care for the needy, weakening the nation.

Local land-use regulations also make America more unequal. My colleague Raj Chetty and his coauthors have produced an “opportunity atlas” that shows where poor Americans have the best chances of growing up to be successful. Their primary measure of opportunity is the adult income of children whose parents were poorer than three-fourths of their contemporaries at the time when the child was born. In the figure below, I sorted metropolitan areas based on this measure and grouped them into quintiles. The figure shows the average Wharton Land Use Index from 2006 for each quintile. As the figure reveals, land-use regulations are strictest in areas that offer poor children the most economic opportunity.

When we zone out building in opportunity-laden areas, we are zoning out the American dream.

How can policymakers change this situation? It won’t be easy. Getting homeowners in prosperous suburbs to change their zoning rules by telling them that it is good for the country or for the environment is not going to work—that would mean asking them to take actions that would lower the value of their largest asset.

Bigger cities offer a more promising chance for reform, since they contain a broader community than just homeowners: banks, which want to lend to both builders and buyers; advocates of low-cost housing; and employers, who want cheaper housing that will make it easier for them to hire less expensive labor. In fact, the most effective advocate for zoning reform that I have heard was the CEO of a large Massachusetts restaurant chain, who complained to then-governor Mitt Romney that high housing costs were killing his ability to make ends meet.

Economist and political scientist Clemence Tricaud has studied the impact of merging jurisdictions in France. She finds that when smaller jurisdictions get folded into bigger ones, the now-combined jurisdiction permits more housing. This provides our best social-science evidence that larger jurisdictions are open to more building. I’m not arguing for a nationwide campaign to merge towns together but am suggesting that housing reformers focus on bigger cities rather than smaller towns.

If we do want to change land-use regulations in smaller jurisdictions, the path runs through state legislatures, which hold almost unfettered power to change local zoning. They can provide ways to bypass local codes, as Massachusetts did 50 years ago with Chapter 40B (which empowered the state to permit affordable housing projects in expensive areas), or by creating financial incentives to encourage localities to allow more construction.

Robert Ellickson and David Schleicher, both of Yale Law School, are two of the wisest legal scholars on land-use regulation. Ellickson essentially pioneered the field in 1975, and he has written a terrific recent book: America’s Frozen Neighborhoods: The Abuse of Zoning. I’ll borrow flagrantly from him here in looking at California.

For 50 years, California has had a Regional Housing Needs Act, which allegedly allocates an amount of housing to all of California’s jurisdictions and imposes penalties if these areas don’t allow enough building. In theory, this seems like a good mechanism; in practice, the entity has proved fairly toothless. Operationally, California’s Department of Housing and Community Development allocates housing assessments, and communities submit housing provisions—changes to such zoning reforms—which will let them meet those assessments. If cities fail to reach their assessments, based on actual building, they lose the ability to reject projects on an ad hoc basis. But the act still leaves noncompliant communities free to zone as restrictively as they wish. Consequently, it accomplishes little in its current form.

In 1990, California’s Housing Accountability Act introduced a potentially far more powerful tool: the “builder’s remedy.” The basic idea was that, in communities that fail to meet their quota, state zoning regulations would permit construction of affordable and middle-income housing, overriding local rules. This bypass echoed Massachusetts 40B and seemed potentially powerful, either directly permitting more housing or inducing localities to meet their allocations to avoid losing control.

Unfortunately, for 30 years, the remedy has had little impact. Chris Elmendorf, a legal scholar at the University of California–Davis, thinks that “the most probable answer” for why the builder’s remedy has been so ineffective is that it is “so poorly drafted and confusing that developers of ordinary prudence haven’t been willing to chance it.” In 2019, California passed its Housing Crisis Act (SB 330), which aimed at empowering the builders and clearing away the legal confusion. If California’s courts don’t gut the builder’s remedy, as they might, this should have much more power than California’s SB 9, which passed last year, to much fanfare. That law lets people split their lots in two—a change in the right direction but one unlikely to deliver the large-scale housing construction that California needs.

The California approach provides a possible model for other states. As Ellickson recommends, legislatures could create state agencies that would oversee local regulatory behavior. An effective agency would have a single objective: ensuring the construction of moderately priced housing in desirable locations. The agency’s leadership would be held accountable for achieving that end. And the agency must have real power, which it would if it had the authority to permit construction in nonperforming communities.

When California regulates, it affects the rest of the country. People who want to move to California are hurt by these regulations, but they get no vote in the matter. The same is true of New York City’s regulations. The federal government can play an important role in pushing local governments to consider the national implications of their regulatory behavior.

Ellickson reminds us that long ago the federal government, under Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover, encouraged the spread of zoning laws across the United States. As Hoover wrote in 1926: “When the advisory committee on zoning was formed in the Department of Commerce in September, 1921, only 48 cities and towns, with less than 11,000,000 inhabitants, had adopted zoning ordinances,” but “by the end of 1923, a little more than two years later, zoning was in effect in 218 municipalities, with more than 22,000,000 inhabitants, and new ones are being added to the list each month.” Hoover’s words came from the foreword he wrote to a Department of Commerce document containing “A Standard State Zoning Enabling Act under which Municipalities may adopt Zoning Regulations.” In Hoover’s words, “The importance of this standard State zoning enabling act can not well be overemphasized” because state legislatures just borrow the act’s verbiage. Today, the federal government could draft model legislation to create a state housing oversight agency that would make it easier for legislatures to undo the harm that followed from Hoover’s blueprint.

More ambitiously, Washington could provide financial incentives for state legislatures to act. We are in the midst of a great infrastructure push. Why couldn’t national infrastructure spending be more generous to states that ensure that it is easier to build? After all, the benefits of a new road or highway will be much greater if new housing can be built to take advantage of it. Embracing sensible cost-benefit analysis for federal spending that considers the prospect of new building should effectively make that spending contingent on the ability to build. This will give state legislators who want to permit more housing the ability to say to their colleagues: “We’re going to lose access to federal highway funding if we don’t pass legislation that gives more freedom to local property owners.”

Local zoning has become a national issue. Overregulation hurts our national GDP, leads to more carbon emissions, and hampers upward mobility. It is time for the nation as a whole to pursue a broader solution.

Top Photo: When the housing market works correctly, housing becomes just another good that is relatively easy to build; when housing supply gets restricted, prices inflate and bubbles can develop. (DAVID J. PHILLIP/AP PHOTO)