New York City Council member L. Daneek Miller was sure that he was making a brilliant point. The problem with the city’s welfare-to-work program, he thundered last November, was that “it’s a broken system that placed low-skilled workers in low-wage jobs.” Miller supports instead a plan to shift low-skilled workers into higher-paying jobs through the magic of municipal statism for social services. Wall Street, Madison Avenue, and the growing tech sector will foot the bill. It all sounds perfectly reasonable—if it weren’t so wrong.

Mayor Bill de Blasio has tried to be cautious when it comes to policing. He worries that a crime spike will produce an angry citywide reaction that would threaten his political career. But when it comes to welfare reform, the other great advance of the Giuliani/Bloomberg years, de Blasio shows no such caution. He has turned the city’s massive Human Resources Administration over to former Legal Aid Society attorney Steven Banks, a leading “welfare rights” advocate, whose principal contribution over the years has been to tie up the city in litigation.

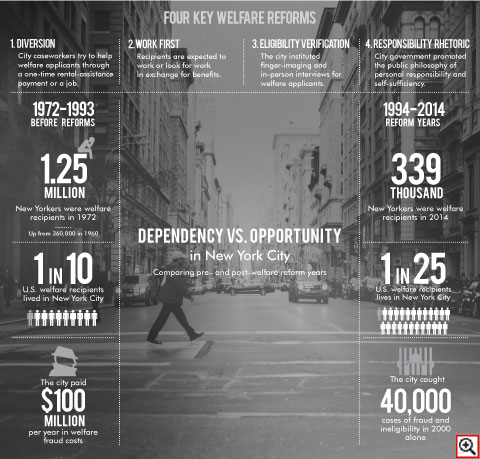

De Blasio can be more aggressively liberal on welfare because most New Yorkers are barely aware of the policies that reduced the welfare rolls from 1.1 million, when Giuliani took over from de Blasio mentor David Dinkins, to the current 350,000. Giuliani’s reforms, devoted to getting people back to work, were so successful that 75 percent of those placed into jobs remained off welfare a year later. From 1994 to 2009, work rates for New York’s single mothers rose from 43 percent to 63 percent (during a period when workforce participation nationwide declined). Even after the 2008 recession, child poverty in New York City in 2011 was almost 10 percentage points lower than in 1993, the year before welfare reform began.

Now de Blasio proposes to replace these proven successes with policies that have already failed in the past. Reviving the hoary notion that entry-level work represents “dead-end jobs,” de Blasio suggests that people on welfare are owed more than an opportunity to work. Job training and “seat time” in a classroom will displace the current system of “rapid placement” into a job. The newly created Mayor’s Office of Workforce Development proposes a vast new program of job training and enhanced “education,” on the theory that a new version of the old failure will reduce inequality in New York. De Blasio’s plan, notes former Giuliani welfare commissioner Jason Turner, “acknowledges that welfare skills training does not work—but then goes on to recommend a ‘new and improved’ version.”

Some critics suggest that de Blasio’s proposals would take us back to the bad old peak-welfare days of the late 1980s and early 1990s—but in fact, his proposals would reach back even further, to 1933 and Franklin Roosevelt’s ill-fated National Industrial Recovery Act. In de Blasio’s version, New York will use its considerable purchasing power, contracts, subsidies, tax breaks, and regulatory powers to remedy the “mismatch” between the demand for skilled workers and the almost 25 percent of the total labor force that earns less than $20,000 per year. De Blasio’s team would create NIRA-style “Industry Partnerships” that “will work to determine the skills and qualifications that employers need.” Low-skilled workers will be prepared for skilled work through better training and education—and the city will use its “leverage” by imposing “penalties” on employers for noncompliance. Those who comply (or perhaps contribute sufficiently to de Blasio’s political coffers) will receive the “New York City Good Business Seal,” a throwback to the famous NIRA Blue Eagle emblem. This policy will then supposedly allow the city to reimburse workforce agencies on the basis of job quality, instead of on the quantity of job placements.

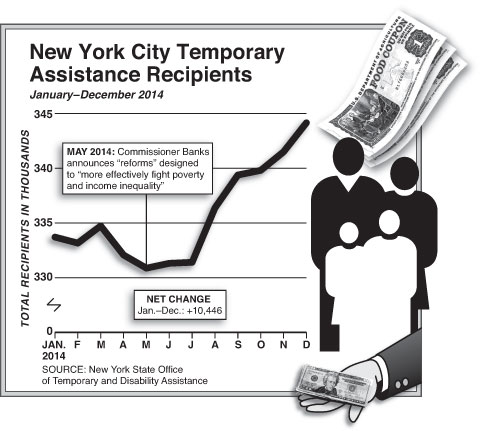

Nevertheless, as Mayor de Blasio’s task force acknowledges, “There is very little data that can be used to validate good job quality and business practices.” Lots of data exist, however, on the most fundamental measure: how many people are on the city’s welfare rolls. And early indications show that de Blasio’s reforms are already starting to reverse the trend toward self-sufficiency. Research from the Manhattan Institute’s Stephen Eide shows that, in the 12 months ending December 2014—corresponding with the mayor’s first year in office—the city’s welfare rolls added a net of more than 10,000 new recipients. The growth is even more alarming than the net figure suggests, since the numbers were still trending downward until May, when Banks was hired; since then, the rolls have grown by 13,000 (see chart).

At the same city council hearing at which Council Member Miller made his case for the de Blasio reforms, Jason Turner explained that, in the real world, low-skilled workers need good work habits before acquiring new skills to enhance earnings. With the exception of Council Member Dan Garodnick of Manhattan, the council politely ignored Turner’s input. They had no questions for a man who had helped implement the successful reforms that they propose to discard. Too many interests allied with the de Blasio administration—including city-subsidized “community organizations,” some of which date from the 1960s—were about to be handed a new source of patronage.

The NIRA was dismantled when the Supreme Court struck it down as an unconstitutional extension of federal power. De Blasio’s gimcrack proposals may last longer, but they have no better chance of success.