In Britain, government spending is now so high, accounting for more than half of the economy, that it is increasingly difficult to distinguish the private sector from the public. Many supposedly private companies are as dependent on government largesse as welfare recipients are, and much of the money with which the government pays them is borrowed. The nation’s budget deficit in 2010, in the wake of the financial crisis, was 10.4 percent of GDP, after being 12.5 percent in 2009; even before the crisis, the country had managed to balance its budget for only three years out of the previous 30.

Deficits are like smoking: difficult to give up. They can be cut only at the cost of genuine hardship, for many people will have become dependent upon them for their livelihood. Hence withdrawal symptoms are likely to be severe; and hardship is always politically hazardous to inflict, even when it is a necessary corrective to previous excess. This is what Britain faces.

For some politicians, running up deficits is not a problem but a benefit, since doing so creates a population permanently in thrall to them for the favors by which it lives. The politicians are thus like drug dealers, profiting from their clientele’s dependence, yet on a scale incomparably larger. The Swedish Social Democrats understood long ago that if more than half of the population became economically dependent on government, either directly or indirectly, no government of any party could easily change the arrangement. It was not a crude one-party system that the Social Democrats sought but a one-policy system, and they almost succeeded.

For countries that operate such a one-policy system, especially as badly as Britain does, economic reality is apt to administer nasty shocks from time to time, requiring action. When the new coalition government, led by David Cameron of the Conservatives and Nick Clegg of the Liberal Democrats, came into power last year, the economic situation was cataclysmic. The budget deficit was vast; the country had a large trade deficit; the population was among the most heavily indebted in the world; and the savings rate was nil. Room for maneuver was therefore extremely limited.

The previous years of fool’s gold—asset inflation brought by easy credit—had allowed the Labour government to expand public spending enormously without damaging apparent prosperity. Labour’s Gordon Brown, chancellor of the exchequer from 1997 to 2007 and then prime minister for three years, boasted that he had found the elixir of growth: his boom, unlike all others in history, would not be followed by bust. During Brown’s years in office, however, three-quarters of Britain’s new employment was in the public sector, a fifth of it in the National Health Service alone. Educational and health-care spending skyrocketed. The economy of many areas of the country grew so dependent on public expenditure that they became like the Soviet Union with supermarkets.

Britain was living on borrowed money, consuming today what it would have to pay for tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, and the day after that; the national debt increased at a rate unmatched in peacetime; and when the music stopped, the state found itself holding unprecedented obligations, with no means of paying them. Without aggressive reforms, it was clear, Britain would soon have to default on its debt or debauch its currency. Both alternatives were fraught with dire consequences.

In the end, the new government chose to attack the deficit from both ends: by cutting spending and by increasing taxes. As many commentators noted, this approach risked a reduction of aggregate demand so great that short-term growth would be impossible and a prolonged recession, even depression, would be probable. Domestic demand would plummet, and export-led growth, many feared, would not be able to rescue the economy, for two reasons: first, Britain’s industry was so debilitated that its competitiveness in sophisticated markets could not be restored from one day to the next by, say, a favorable change in the exchange rate; and second, the country’s traditional export markets were experiencing difficulties of their own.

But the general economic argument was not what fueled the fierce intellectual and street protests that in recent months have opposed the government’s efforts to reduce the deficit—efforts so far more symbolic than real, for state borrowing requirements have only increased since the coalition’s arrival in power. Nor were the protests directed against the tax increases. Since the end of World War II, the British have grown accustomed to the idea that the money in their pockets is what the government graciously consents to leave them after it has taken its share. When (as rarely happens) the chancellor of the exchequer reduces a tax instead of increasing it, even conservative newspapers say that he has “given money away,” as if all money came from him in the first place. The wealth is the government’s and the fullness thereof: where such a belief is prevalent, no tax increase will seem either illegitimate or oppressive.

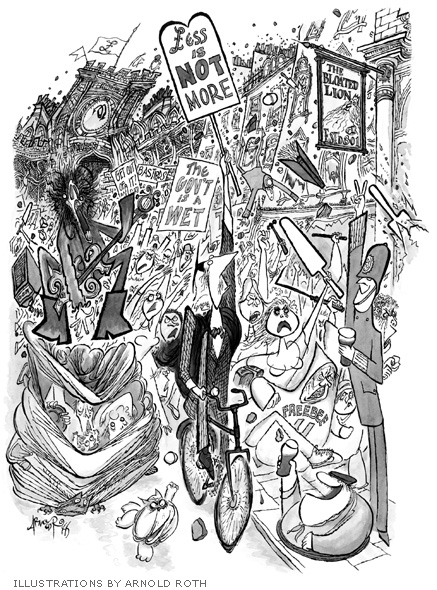

What did provoke the furious opposition was the government’s proposals to reduce spending in such areas as education and health care, as well as its plan to increase tuition at public universities. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, disproportionately consisting of public workers and students, gathered on London’s streets. One demonstrator, Charlie Gilmour, became famous. The adopted son of the lead guitarist of Pink Floyd, with a personal fortune estimated at $160 million, he was the very image of the caviar anarchist. Dressed expensively in black and booted to match, his dark locks flowing poetically behind him, he stomped the roofs of cars and stormed the Cenotaph, the most important war memorial in the country. Later, he claimed not to have realized what it was, though he was a student—of history, no less—at Cambridge, and you would need to be either illiterate or virtually blind to miss the words our glorious dead inscribed on it. His contrition and appearance in court in a suit and tie, in an attempt to avoid a prison sentence, afforded the nation some light relief in these most difficult times.

The student demonstrators were right to be angry, but their anger was misdirected. They were merely protesting the prospect of paying for their education, which would force upon them or their parents the difficult but important question of whether the university education that they received was worth the debt that they would incur to pay for it. How easy it is to proceed to college without having to consider such sordid matters, or make such difficult calculations, because the state—that is to say, the taxpayer—subsidizes you!

In fact, British young people have been subjected to a gross deception, which, if they recognized it, would make them far angrier than the demonstrators were. The previous government decreed that 50 percent of British youth should attend university, irrespective of students’ educational attainment or of the economy’s capacity to make use of so many graduates. In so doing, it doubled state expenditure on education in only eight years. This centralized planning had a predictable effect: the standard of university teaching and education fell significantly, as did the value of the average degree. While the number of graduates expanded, employers complained that young Britons were increasingly unable to write a simple sentence properly or do basic arithmetic.

For the students, however, the connotation of university education lagged behind its denotation: in other words, though education declined in quality, students felt entitled to the same advantages that had accrued to graduates back when education was better. Graduates grumbled about the lowly positions that they had to take after college, which people who had not gone to college would once have satisfactorily filled. It was perhaps unsurprising, then, that students, suddenly asked to fund their delayed maturation for themselves, should explode in wrath. They saw the reform not as an attempt to align education with the needs and capacities of the real economy—by making students question the value of education and by encouraging universities to offer something of real value—but as a means of restricting access to education to the rich; this despite the fact that the total loan necessary to obtain a university education, supposedly an advantage for life, would still be a fraction of an average mortgage.

The biggest demonstration against the government’s proposals was on March 26. A quarter of a million people took to the streets—in solidarity with themselves. Many were teachers protesting the proposed cuts in education spending. Yet after a compulsory education lasting 11 years and costing, on average, $100,000 per pupil, about a fifth of British students who do not attend college after high school are barely able to read and write, according to a recent study from Sheffield University. Considering the disastrous personal consequences of being illiterate in a modern society, this is a gargantuan scandal, amounting to large-scale theft by the educational authorities. No anarchist ever smashed a window because of this scandal, however; and so it is impossible to resist the conclusion that the demonstration was in defense of unearned salaries, not (as alleged) of actual services worth defending.

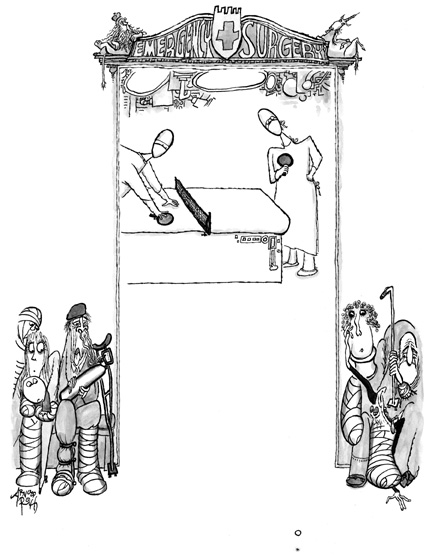

Protesters were also agitating against proposed cuts to the National Health Service. The cumulative increase in spending on the NHS from 1997 to 2007 was equal to about a third of the national debt. After all this spending, Britain remains what it has long been: by far the most unpleasant country in Western Europe in which to be ill, especially if one is poor. Not coincidentally, Britain’s health-care system is still the most centralized, the most Soviet-like, in the Western world. Our rates of postoperative infection are the highest in Europe, our cancer survival rates the lowest; the neglect of elderly hospital patients is so common as to be practically routine. One has the impression that even if we devoted our entire GDP to the NHS, old people would still be left to dehydrate in the hospitals.

From 1997 to 2007, the number of people employed by the NHS rose by a third, with the number of doctors employed by it doubling and overall remuneration for personnel increasing by 50 percent per head. Yet it became ever more difficult for patients to see the same doctor twice, even during a single hospital admission; the standard of medical training declined, according to 99 percent of surgeons in training, while senior surgeons admitted that they wouldn’t want their trainees operating on them; and a government inquiry found that productivity in the NHS—admittedly, not easy to measure—had declined markedly.

Wherever one looks into the expanded public sector, one finds the same thing: a tremendous rise in salaries, pensions, and perquisites for those working in it. In Manchester, for example, the number of city employees earning more than $85,000 a year rose from 68 to 1,746 between 1997 and 2007. In effect, a large public service nomenklatura was created, whose purpose, or at least effect, was to establish an immense network of patronage and reciprocal obligation: a network easy to install but hard to dislodge, since those charged with removing it would be the very people who benefited most from it.

One of the Labour government’s gifts to public employees was overly generous pensions. While Gordon Brown raised taxes on pensions funded by private savings, he increased pensions for public-sector workers. In many cases, these government pensions, if they had not been paid for with current tax receipts and (to a growing extent) borrowing, would have required funds of millions of dollars to support. In other words, Brown was Bernard Madoff with powers of taxation. I leave it to readers to decide whether that makes him better or worse than Madoff.

The press usually defends the public sector, viewing it as an expression of the general will and a manifestation of a rationally planned society, manned by selfless workers. It was thus quick to warn of the direst possible consequences of Cameron and Clegg’s austerity measures: school overcrowding, unnecessary deaths in hospitals, fewer or no social services. The streets would run with blood; mass poverty would return.

Unfortunately, it does not follow from the existence of immense waste in the public sector that budget cuts will target that waste. After all, most of the excess is in wages, precisely the element of government spending that those in charge of proposed reductions will be most anxious to preserve. It is therefore in their interest that any budget reduction should affect disproportionately the service that it is their purpose to provide: cases of hardship will then result, the media will take them up, and the public will blame them on the spending cuts and force the government to return to the status quo ante. Another advantage of cutting services rather than waste, from the perspective of the public employee, is that it makes it appear that the budget was previously a model of economy, already pared to the bone.

I have seen it all before, whenever cuts became necessary in the NHS budget, as periodically they did. Wards closed, but the savings achieved were minimal because labor legislation required the staff—the major cost of the system—to be retained. Surgical operations were likewise canceled, though again, the staff was kept on. To effect any savings in this manner, it was necessary for the system to become more and more inefficient and unproductive. It was as if the bureaucracy had reversed the cry of the people at the beginning of Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno, “More bread! Less taxes!,” replacing it with “More taxes! Less bread!”

So it is not surprising that the Guardian, which one could almost call the public-sector workers’ mouthpiece, has reported that hospital emergency departments are already feeling the budgetary pressure and risk being overwhelmed, even before the cuts have been implemented in full. Meanwhile, one can still find plenty of bureaucratic jobs advertised in the Health Service Journal, the publication for nonmedical employees of the NHS. One hospital seeks an Associate Director of Equality, Diversity, and Human Rights; another is looking for an interim Deputy Director of Operations and Transformation. Part of the “transformation” in that case seems to be a reduction in the hospital’s budget, and it is instructive that the person who will be second in command of that reduction will be paid between $1,000 and $1,300 per day.

The legacy of Britain’s previous government, which expanded the public sector incontinently, is thus an almost Marxian conflict of classes, not between the haves and have-nots (for many of the people in the public service are now well-heeled indeed) but between those who pay taxes and those who consume them.

In this conflict, one side is bound to be more militant and ruthless than the other, since taxes are increased incrementally—and everyone is already accustomed to them, anyway—but jobs are lost instantaneously and catastrophically, with the direst personal consequences. Thus those who oppose tax increases and favor government retrenchment will seldom behave as aggressively as those who will suffer personally from budget reductions. Moreover, when, as in Britain, entire areas have lived on government charity for many years—with millions dependent on it for virtually every mouthful of food, every scrap of clothing, every moment of distraction by television—common humanity dictates care in altering the system. The extreme difficulty of reducing subventions once they have been granted should serve as a warning against instituting them in the first place, but in Britain, it appears, it never will. We seem caught in an eternal cycle, in which a period of government overspending and intervention leads to economic crisis and hence to a period of austerity, which, once it is over, is replaced by a new period of government overspending and intervention, promoted by politicians, half-charlatan and half-self-deluded, who promise the electorate the sun, moon, and stars.

When our new government came into power—after a period in opposition during which, fearing unpopularity, it failed to explain the real fiscal situation to the electorate—there was broad, if reluctant, acceptance that something unpleasant had to be done; otherwise, Britain would soon be like Greece without the sunshine. But the acceptance was on narrow grounds only, and this is worrying because it implies that we are far from liberating ourselves from the binge-followed-by-austerity cycle. A large part of the public still views the state as the provider of first resort, which means that the public will remain what it now is: the servant of its public servants.

As soon as the crisis is over, though this may not be for some time, the politicians are likely again to offer the public security and excitement, wealth and leisure, education and distraction, capital accumulation without the need to save, health and safety, happiness and antidepressants, and all the other desiderata of human existence. The public will believe the politicians because—to adapt slightly the great dictum of Louis Pasteur—impossible political promises are believed only by the prepared mind. And our minds have been prepared for a long time, since the time of the Fabians at least.