Last year, as the nation’s colleges anticipated the Supreme Court’s effective ban on racial preferences, I published a Manhattan Institute report projecting how universities might respond. Now, more than a year after the Court’s ruling in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, schools are publishing their Class of 2028 demographic data, with some reporting large declines in black and Hispanic enrollment, while others show little change. Let’s review my predictions, and the results.

My analysis here focuses on the nation’s elite schools. Most American colleges aren’t very selective, and thus have little room to prefer some applicants to others. Middle-tier colleges can likely maintain their previous demographic balance by enacting moderate reforms, such as automatically admitting students who graduated in the top 10 percent of their high school’s class.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

At the top-tier schools, however, an affirmative-action ban should have forced dramatic changes. Decades of research suggest that if those colleges straightforwardly complied with such a ban—ceasing to consider applicants’ race, while leaving the rest of the process unchanged—black admissions could fall by more than half. Since racial gaps in academic qualifications are most dramatic at the high and low ends of the distribution, highly selective colleges that want to match their demographics to the American population’s need to enact aggressive preference policies. This explains why black applicants to Harvard before the ruling were four times more likely to be admitted than were similarly qualified whites.

Yet, as I noted in my report, no Court ruling would force colleges to remove racial preferences and change nothing else. At a minimum, top colleges responding to an affirmative-action ban could be expected to expand recruiting efforts and expand preferences for low-income applicants. More aggressively, they might extensively calibrate their socioeconomic preferences to target blacks and Hispanics—such as giving a boost to kids who come from single-parent families or who speak a language other than English at home.

Before the ruling, schools had increasingly refused to require standardized testing, giving them more room to weigh other factors—and they'd need a lot of this leeway if they wanted to achieve a desired racial balance without considering race itself. Banning affirmative action, paradoxically, could pressure schools to make admissions less meritocratic.

What happened after the ruling?

Let’s start by noting a positive: Many elite schools have restored testing requirements since the Court’s decision, noting that exam scores are strong predicters of college success and effective in identifying talented students of all backgrounds. Harvard even reneged on a promise not to require tests through the 2026 admissions cycle; it will mandate them again starting next year.

Still, the early demographic data suggest that schools’ compliance with the affirmative-action ban is mixed.

Some schools seem to be adhering to the ruling. As Peter Arcidiacono and Tyler Ransom have discussed in City Journal, the black share of MIT’s freshman class fell to 5 percent this year, from an average of about 13 percent in the previous four years, while the Hispanic share fell to 11 percent from an average of 15 percent. White enrollment held about steady, and Asian enrollment grew to 47 percent from an average of 40 percent. This is about what one might expect under straightforward compliance, though MIT did expand its recruiting and financial aid after the decision. Amherst, and to a lesser extent Tufts, the University of Virginia, and Rice have also reported falling black shares of their student bodies.

Other schools’ compliance is less clear. At Yale—where the admissions office does not see applicants’ self-reported race—the black and Hispanic shares remained flat, the Asian share fell six points, and the white share rose four. Duke and Princeton reported similar results after the Court’s ruling: black and Hispanic shares flat, the Asian share down.

Without detailed admissions data (and likely a lawsuit to force their disclosure), it’s not possible to say how exactly these schools adjusted their processes to achieve these perplexing results. Notably, Yale, Duke, and Princeton all joined a legal brief before the Court’s ruling arguing that explicit consideration of race in the admissions process was necessary to prevent large declines in black enrollment at elite schools.

Much remains to be seen. Other schools have yet to release their breakdowns, and comprehensive federal data will not be available soon. It’s also possible that this year’s numbers won’t hold into the future. But one thing is clear: the battles over affirmative action, in the courts and on campus, are far from over.

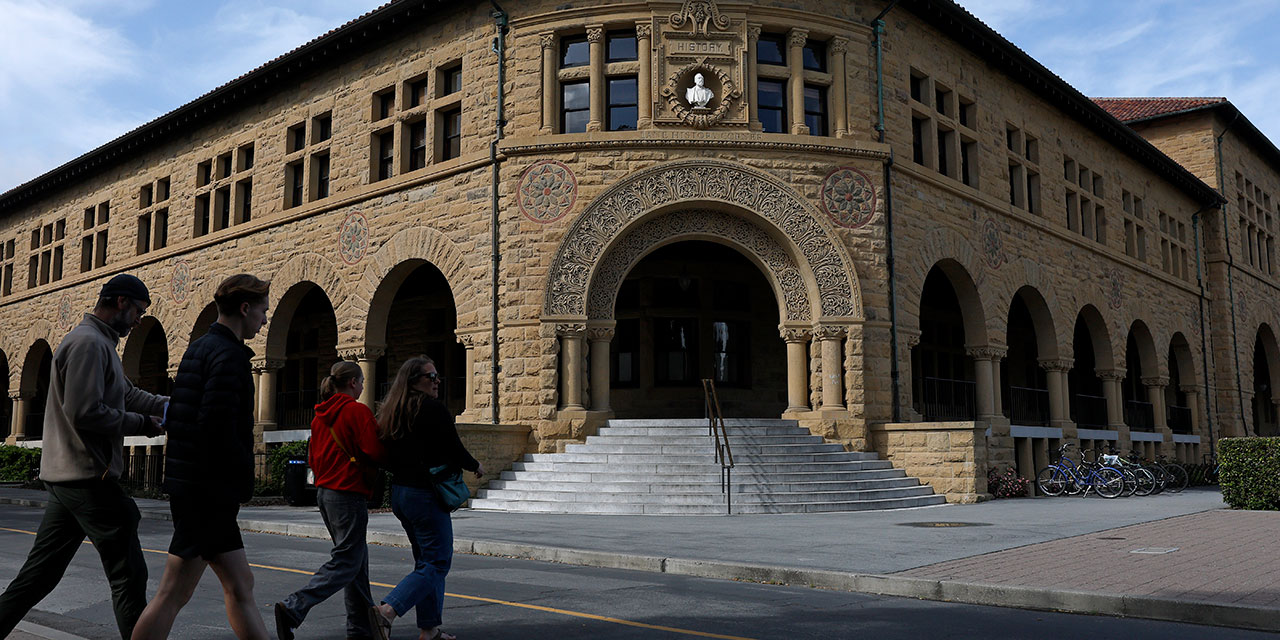

Photo: Pgiam / iStock via Getty Images