Climate-change science is “settled,” say proponents of anthropogenic (human-induced) global warming, or AGW: the earth is getting warmer, and human activities are the reason. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), set up by the United Nations in 1988, has issued five assessment reports since its founding. In its most recent, in 2013, the IPCC stated that it was now “95 to 100 percent certain” that human activities—especially fossil-fuel emissions—are the primary drivers of planetary warming. Frequent news reports—such as the story of the melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a process that some scientists say is irreversible—seemingly confirm these conclusions.

And yet, highly credentialed scientists, including Nobel Prize–winning physicist Ivar Giaever, reject what is often called the “climate consensus.” Giaever resigned from the American Physical Society in protest of the group’s statement that evidence of global warming was “incontrovertible” and that governments needed to move immediately to curb greenhouse-gas emissions. Sixteen distinguished scientists signed a 2012 Wall Street Journal article, in which they argued that taking drastic action to “decarbonize” the world’s economy—an effort that would have major effects on economic growth and quality of life, especially in the developing world—was not justified by observable scientific evidence. And, like Giaever, they objected to the notion of a climate consensus—and to the unscientific shutting down of inquiry and the marginalization of dissenters as “heretics.” Most recently, renowned climate scientist Lennart Bengtsson stepped down from his post at a climate-skeptic think tank after he received hundreds of angry e-mails from scientists. He called the pressure “virtually unbearable.”

Another dissenter, the American atmospheric physicist Murry Salby, has produced a serious analysis that undermines key assumptions underpinning the AGW worldview. His work and its reception illustrate just how unsettled climate science remains—and how determined AGW proponents are to enforce consensus on one of the great questions of our age.

In April 2013, concluding a European tour to present his research, Salby arrived at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris for a flight back to Australia, where he was a professor of climate science at Macquarie University. He discovered, to his dismay, that the university had canceled the return leg of his nonrefundable ticket. With Salby stranded, Macquarie then undertook misconduct proceedings against him that swiftly culminated in his dismissal. The university claimed that it did not sack Salby for his climate views but rather because he failed to “fulfill his academic obligations, including the obligation to teach” and because he violated “University policies in relation to travel and use of University resources.”

Salby and his supporters find it hard to believe the school’s claims. Salby’s detractors point to reports of his investigation by the National Science Foundation (NSF) for alleged ethical improprieties, claims surrounding which surfaced on an anti-climate-skeptic blog, along with court papers relating to his divorce. Salby has indeed been embroiled in conflicts with the NSF—the organization debarred him from receiving research grants for three years, even though, teaching in Australia, he wasn’t eligible, anyway—and with the University of Colorado, where he taught previously and was involved in a decade-long dispute with another academic. At one point, the NSF investigated the disappearance of $100,000 in Salby’s research funds, which, in the wake of the investigation, was returned to Salby’s group. However, all these matters have involved bureaucratic rights and wrongs. They have no bearing on his science, just as Antoine Lavoisier’s being a tax farmer had no bearing on his demolition of the phlogiston theory of combustion. And Salby had earned high marks as a scientist. He originally trained as an aerospace engineer before switching to atmospheric physics and building a distinguished career. He taught at Georgia Tech, Princeton, Hebrew, and Stockholm Universities before coming to the University of Colorado, and he was involved as a reviewer in the IPCC’s first two assessment reports.

Starting in the late 1990s, Salby began a project to analyze changes in atmospheric ozone. His research found evidence of systematic recovery in ozone, validating the science behind the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which introduced specific steps for curtailing ozone-depleting gases. Preparing to write a graduate-level textbook, Physics of the Atmosphere and Climate, later published by Cambridge University Press and praised by one reviewer as “unequalled in breadth, depth and lucidity,” Salby then undertook a methodical examination of AGW. What he found left him “absolutely surprised.”

Most discussion on the science of AGW revolves around the climatic effects of increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. How it got there in the first place—the assumption being that increased carbon dioxide arises overwhelmingly from human activities—is often taken for granted. Yet Salby believed that he had uncovered clear evidence that this was not the case, as his trip to Europe was designed to expose.

The IPCC estimates that, since the Industrial Revolution, humans have released 365 billion tons of carbon from burning fossil fuels. Annual emissions, including those from deforestation and cement production, are less than 9 billion tons. Yet natural carbon cycles involve annual exchanges of carbon between the atmosphere, the land, and the oceans many times greater than emissions from human activities. The IPCC estimates that 118.7 billion tons of carbon per year is emitted from land and 78.4 billion tons from oceans. Thus, the human contribution of 9 billion tons annually accounts for less than 5 percent of the total gross emissions. The AGW hypothesis, as well as all the climate-change policies that depend on it, assumes that the human 5 percent drives the overall change in the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere—and that the other 95 percent, comprising natural emissions, is counterbalanced by absorption of CO2 from the atmosphere by natural processes. Summing it up, the IPCC declared in its fourth assessment report, in 2007: “The increase in atmospheric CO2 is known to be caused by human activities.”

Salby contends that the IPCC’s claim isn’t supported by observations. Scientists’ understanding of the complex climate dynamics is undeveloped, not least because the ocean’s heat capacity is a thousand times greater than that of the atmosphere and relevant physical observations of the oceans are so sparse. Until this is remedied, the science cannot be settled. In Salby’s view, the evidence actually suggests that the causality underlying AGW should be reversed. Rather than increased levels of CO2 in the atmosphere triggering global temperatures to rise, rising global temperatures come first—and account for the great majority of changes in net emissions of CO2, with changes in soil-moisture conditions explaining most of the rest. Furthermore, these two factors also explain changes in net methane emission, the second-most important “human” greenhouse gas. As for what causes global temperatures to rise, Salby says that one of the most important factors influencing temperature is heat exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean.

Why is the IPCC so certain that the 5 percent human contribution is responsible for annual increases in carbon dioxide levels? Without examining other possible hypotheses, the IPCC argues that the proportion of heavy to light carbon atoms in the atmosphere has “changed in a way that can be attributed to addition of fossil fuel carbon”—with light carbon on the rise. Fossil fuels, of course, were formed from plants and animals that lived hundreds of millions of years ago; the IPCC reasons that, since plants tend to absorb more light carbon than heavy carbon, CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels reduce the share of heavy carbon in the atmosphere. But Salby points to much larger natural processes, such as emissions from decaying vegetation, that also reduce the proportion of heavy carbon. Temperature heavily influences the rate of microbial activity inherent in these natural processes, and Salby notes that the share of heavy carbon emissions falls whenever temperatures are warm. Once again, temperature appears more likely to be the cause, rather than the effect, of observed atmospheric changes.

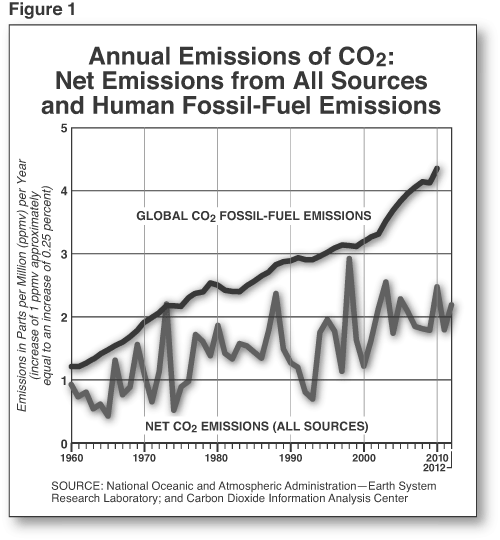

Further, Salby presents satellite observations showing that the highest levels of CO2 are present not over industrialized regions but over relatively uninhabited and nonindustrialized areas, such as the Amazon. And if human emissions were behind rising levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, he argues, then the change in CO2 each year should track the carbon dioxide released that year from burning fossil fuels—with natural emissions of CO2 being canceled out by reabsorption from land sinks and oceans. But the change of CO2 each year doesn’t track the annual emission of CO2 from burning fossil fuels, as shown in Figure 1, which charts annual emissions of CO2, where an annual increase of one part per million is approximately equivalent to an annual growth rate of 0.25 percent.

While there was a 30 percent increase in CO2 fossil-fuel emissions from 1972 to 1993, there was no systematic increase in net annual CO2 emission—that is, natural plus human emissions, less reabsorption in carbon sinks. These data, Salby observes, are inconsistent with the IPCC’s claim to certainty about human causation of rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere. For the better part of two decades, the IPCC has been struggling to explain the wide interannual variability of changes in net CO2 emission (the jagged lower line in Fig. 1). Various causes have been suggested to explain the 1990s slowdown of CO2 growth, “but none fully explains this unusual behavior of the carbon cycle,” as the IPCC conceded in its third assessment report.

Unable to explain natural changes in CO2 emission, the IPCC falls back on its assumption of a strong natural tendency toward equilibrium: over time, natural emissions and absorption balance each other out, leaving mankind responsible for disruptions in the balance of nature. But, as Salby observes, the IPCC merely postulates this tendency without demonstrating it. The IPCC’s confidence in attributing warming to human activities is thus highly questionable—especially since, for the last decade and a half, atmospheric temperatures have not risen, even as CO2 has risen steadily. Further, while observed average global temperature rose just under one degree centigrade in the last century, this didn’t occur as a steady warming. Almost the entire twentieth-century rise came from four decades—a portion of the interwar years and the 1980s and 1990s—less than a third of the overall temperature record.

Were it not for its implications for AGW, Salby’s research on the carbon cycle might be a boon to the IPCC’s troubled effort to explain interannual variability of CO2 emissions. His work offers a coherent picture of changes in net emissions, where the changes closely track a combination of temperature and soil moisture—explaining both the low net emissions of the early 1990s and their peak in 1998. Salby also contends that temperature alone can largely account for the rise in atmospheric CO2 through the earlier part of the twentieth century, when soil-moisture data are inadequate. Net methane emissions track natural surface conditions even more closely.

Another pillar of the IPCC’s case has been the claim, based on ice-core records of CO2 concentrations, that present levels of carbon dioxide are unprecedented. But here, Salby maintains, accounting for the dissipation of CO2 trapped in ice cores—previously ignored—radically alters the picture of prehistoric changes in atmospheric CO2 levels. Even weak dissipation would mean that such changes have been significantly underestimated until now—and would also imply that modern changes in CO2 are not unprecedented. If Salby is right, the IPCC’s unequivocal claim that modern levels of CO2 are at their highest levels in at least 800,000 years would not hold.

In fact, the IPCC’s 2013 assessment tiptoes in Salby’s direction. The ice-core record of atmospheric CO2 exhibits “interesting variations,” the report says, which can be linked to climate-induced changes in the carbon cycle. The assessment also gingerly concedes that the 15-year pause from 1940, when CO2 levels did not rise, was “possibly” caused by slightly decreasing land temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere.

Salby hasn’t been working in a vacuum. Swedish climate scientist Pehr Björnbom has replicated his finding that temperature drives CO2 emission. University of Oslo geosciences professor Ole Humlum published a landmark 2012 paper demonstrating that changes of CO2 follow changes of temperature, implying the same cause and effect. Richard Lindzen, an atmospheric physicist at MIT, believes that Salby is correct about the IPCC’s failure to evaluate the effects of diffusion in ice cores on the proxy CO2 record and to consider sources of lighter carbon other than fossil-fuel burning. Salby is a “serious scientist” whose arguments deserve a hearing, Lindzen says. Fritz Vahrenholt, a former environmental official and CEO of a large renewable-energy company, as well as one of Germany’s leading climate-change skeptics, found Salby’s analysis of CO2 emission levels lagging temperature changes compelling. “Murry Salby opened a door for more investigations and further scientific work,” Vahrenholt says. Will the scientific community pursue the questions that Salby has raised? Vahrenholt is doubtful. “Upholders of AGW don’t take part in discussions where their orthodox view is challenged,” he complains. One way they block off inquiry is to ensure that papers by dissenting climate scientists are not included in the peer-review literature—a problem that Lindzen and Bengtsson have encountered. Indeed, that is what happened to Salby. He submitted a paper on his initial findings to the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. Finding no errors—one reviewer called it “absolutely amazing”—the journal required minor revision. Before Salby could return the revised paper for publication, the editor of a different journal, Remote Sensing, resigned for publishing a paper that departed from the IPCC view, penning an abject confession: “From a purely formal point of view, there were no errors with the review process. But, as the case presents itself now, the editorial team unintentionally selected three reviewers who probably share some climate skeptic notions of the authors.” Shortly afterward, Salby received a letter rejecting his revised paper on the basis of a second reviewer’s claim—contradicted by the first reviewer—that his paper offered nothing new and that all of it had already been covered in the IPCC’s reports.

Salby’s preliminary findings led him to a wider study, in which he determined, among other things, that the observed relationship between global temperature and CO2 differed fundamentally from that described in climate models. His efforts to publish the study ended, at least for the time being, with the termination of his academic post at Macquarie. As of yet, Salby’s climate analyses have appeared only in preliminary form in his peer-reviewed book published by Cambridge University Press.

Unsurprisingly, the consensus view on the carbon cycle remains that human CO2 emissions are “virtually certain” to be the dominant factor determining current CO2 concentrations. Updating the global-warming catechism in a joint 2014 paper, the National Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society declared: “Continued emissions of these gases will cause further climate change, including substantial increases in global average surface temperature.”

If they adhered to the standards established three centuries ago during the Scientific Revolution, the academies would not be able to make such definitive claims. Nineteenth-century astronomer and philosopher of science John Herschel demanded that the scientist assume the role of antagonist against his own theories; the merits of a theory were proved only by its ability to withstand such attacks. Einstein welcomed attempts to disprove the theory of general relativity. “No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong,” he is said to have declared. Because in science, the philosopher Karl Popper reasoned, we cannot be sure what is true but we can know what is false, truth is approached by discarding what is shown to be false. Popper articulated the principle of falsifiability, distinguishing scientific theory from the pseudosciences of Marx and Freud, whose followers, he noted, found corroboration wherever they looked.

The IPCC and other leading scientific bodies also appear to follow a prescientific injunction: “Seek and ye shall find.” The formulations “consistent with” and “multiple lines of evidence” recur throughout IPCC reports. The IPCC’s fifth assessment report, published in 2013, retreated slightly from previous certainty on humans’ contributing the totality of increased CO2. Now, the IPCC expressed a “very high level of confidence,” based, it said, on several lines of evidence “consistent with” this claim. Consistency with a proposition is weak-form science—the moon orbiting the Earth is consistent with pre-Copernican astronomy, after all—and a feature of the pseudosciences that Popper had seen in early-twentieth-century Vienna. In addition to seeking confirmatory evidence, AGW’s upholders often adopt the scientific equivalent of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell when it comes to gaps in scientific knowledge—in particular, those gaps that, if filled in, might conceivably falsify their position. The 2014 National Academy / Royal Society paper ignored entirely the question of interannual variability of net CO2 emission. Rather than acting, as in Herschel’s formulation, as AGW antagonists, the IPCC and the national science academies have become its cheerleaders.

“Climate change is one of the defining issues of our time,” the National Academy / Royal Society paper insists. “It is now more certain than ever, based on many lines of evidence, that humans are changing Earth’s climate. . . . However, due to the nature of science, not every single detail is ever totally settled or completely certain.” With respect to the carbon cycle, this is a serious misrepresentation: it is not a detail but is fundamental to the scientific case for AGW. The implications for AGW of Salby’s analysis, if it holds up, are stark: if AGW means that human CO2 emission significantly modifies global temperatures; or, stronger, that it controls the evolution of global temperatures; or, stronger still, that it forces temperatures to increase catastrophically, then AGW is falsified by the observed behavior.

Its fifth assessment report, in 2013, was the IPCC’s last major chance to make proclamations before the Paris climate conference in December 2015. Despite its slight retreat on the human role in increased CO2, the IPCC raised its level of certainty about human responsibility for temperature increase—from 90 percent in its previous report to at least 95 percent, though this boost was largely the result of a change in definition. The report’s authors did not opine on why there had been little warming in recent years, saying that not enough had been published on the topic. That dearth shouldn’t be surprising to anyone familiar with the state of climate science.

Genuine scientific inquiry is degraded when science becomes politicized. The standards that have prevailed since the Scientific Revolution conflict with the advocacy needs of politics, and AGW would be finished as the basis of a political program if confidence in its scientific consensus were undermined. Its advocates’ evasion of rigorous falsifiability tests points to AGW’s current weakness as a science. As an academic critic of the science on which AGW rests, Murry Salby may have been silenced for now. The observed behavior of nature, from which he draws his analysis, cannot be dismissed so readily.