Christopher Lasch and Michel Foucault are rarely read side by side. Yet the two thinkers praised each other’s work, recognizing themselves as involved in a common project. Both assessed, on the one hand, the ways elites use networks of expertise and injunctions to moral “liberation” to strengthen their domination—and, on the other, the ways that modern people have come to look for knowledge of themselves from such experts. They shared a sense that beneath progressive policies for public welfare, demands for sexual freedom and identity-based affirmation, and therapeutic practices of self-discovery lies a dangerous potential for authoritarianism and alienation.

Many American readers of the 1970s got their first introduction to Foucault from Lasch, who reviewed the English translation of Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic (1963) for the New York Times in 1976, and his History of Sexuality Part One (1976) in Psychology Today two years later. Lasch brilliantly summarized Foucault’s argument that the movement for sexual liberation had misrepresented the past as purely repressive, while establishing a new sort of power over sexuality and the secrets of intimate life, vested now in “medical jurisdiction” and “therapeutic authority.” Their approaches nevertheless had important differences, with Lasch tending to criticize feminism and to express nostalgia for a vanished moral sense that he described as populist—concerns that Foucault, more oriented toward individual freedom, approached only in such rare moments as his early support for the Iranian Revolution.

The culmination of Lasch and Foucault’s relationship came at the University of Vermont in 1982, by which time Foucault, with an appointment at UC Berkeley, had become a star in American academia. Lasch was one of several scholars invited to comment on Foucault’s work during a three-week period in which Foucault himself gave a series of lectures, “Technologies of the Self.” Foucault attributed their inspiration to Lasch’s Culture of Narcissism (1979), in which Lasch had argued that anxious individuals, deprived of economic security and cultural bonds, were investing their self-image, and therapeutic projects of self-discovery, with unprecedented importance.

Foucault perhaps was flattering his hosts, but his intellectual trajectory had indeed taken a parallel turn with that of Lasch. In his final lecture, Foucault noted that while his early work tracked how institutions like asylums, hospitals, and prisons—and bodies of knowledge like psychiatry, medicine, and criminology—define “who we are” by excluding the abnormal, his work following History of Sexuality focused on how individuals come to understand themselves in consultation with a range of supposed experts of self-knowledge. Foucault worked from a broad perspective—tracking such expertise from the philosophers of classical Athens to priests in late antiquity to psychiatrists today—and avoided Lasch’s more personal focus on how modern narcissism makes us miserable. But the two had a common sense of the problem.

By 1991, however, seven years after Foucault’s death, and three years before his own, Lasch dismissed the French thinker, whose influence he had spread and whom he in turn had influenced. In an article for Salmagundi, to which he often contributed, titled “Academic Pseudo-Radicalism: the Charade of Subversion,” Lasch attributed to Foucault the claim that “knowledge of any kind is purely a function of power.” In thus crediting to Foucault a position so obviously self-defeating that it is hard to imagine any thinker holding it, Lasch failed to notice a convergence between the work of his late period and that of Foucault’s a decade earlier.

Toward the end of their lives, both men turned to the theme of religion, arguing that it provided critical cultural and psychological resources necessary for individuals to become meaningfully autonomous. They moved toward an understanding that, in order to become the sort of independent selves on whom liberal democracy depends, we need what Foucault called “discipline” or “ascesis”—the ability to bind ourselves to other people who help us both to keep our commitments and to remake ourselves. In his final book, Revolt of the Elites (1994), Lasch offered a similar perspective on the value of religion without demonstrating an awareness that he was traveling the same road as Foucault.

In Foucault’s home country of France, Lasch has been taken up today in certain corners of the radical Left unafraid of sounding at times like conservative moralists. Jean-Claude Michéa, the heterodox Marxist, has written prefaces to recent French editions of Culture of Narcissism and Revolt of the Elites that highlight Lasch’s critiques of globalization and the capitalist culture of self-fascination. Lasch also can be heard in the French collective Tiqqun’s Raw Materials For a Theory of the Young-Girl (1999), a scornful attack on consumerism, spectacle, and narcissism, seen as embodied in the modern sexually liberated woman.

In the United States, meantime, some of Lasch’s contemporary interpreters, such as Geoff Shullenberger, are also seeing Foucault afresh. From Shullenberger’s perspective (in dialogue with my own work on Foucault), it is possible to see how Lasch and Foucault came to criticize both traditional Marxism and the new identity-based radicalisms that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s.

Conservatives often try to make sense of their cultural adversaries through the genealogy of their ideas, tracing “wokeness” back to such supposed intellectual forbears as, ironically, Foucault. Others reach back, still more unhelpfully, to Marx and Hegel, or analyze wokeness as a new religion. Part of the value of Lasch and Foucault is that they can redirect our attention away from such wrong paths in intellectual history toward the systems of knowledge, institutions, and practices by which Americans have become so fixated on questions of identity in the first place.

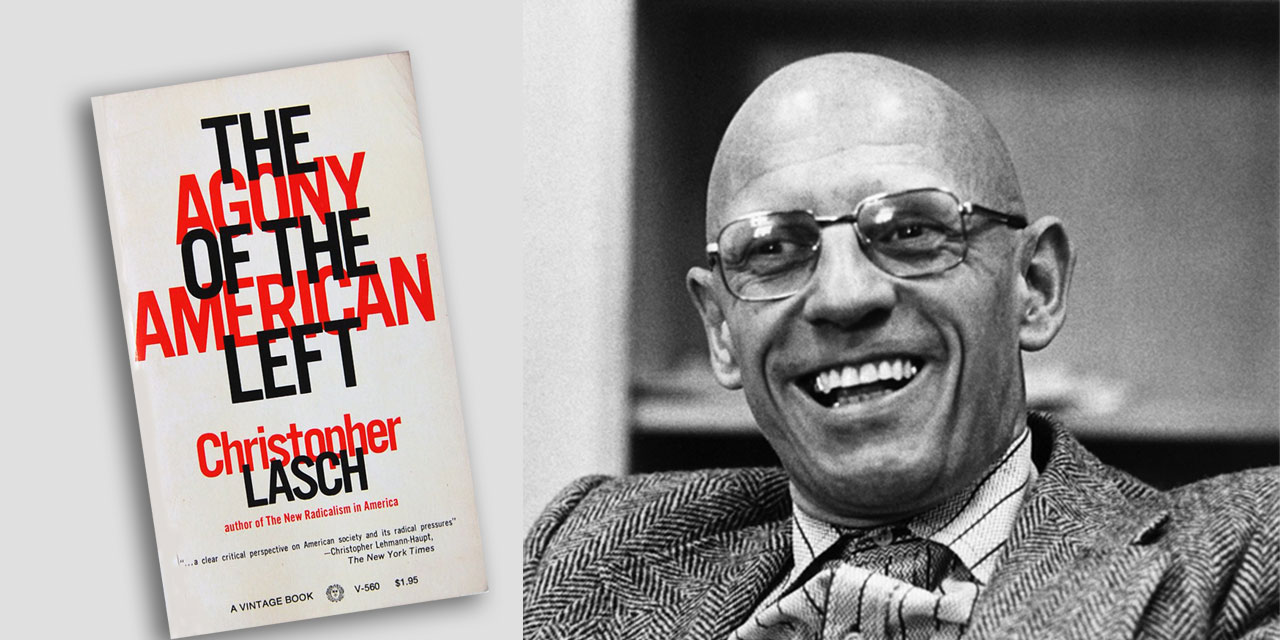

Photo: On left, book cover design by Arnold Skolnick for The Agony of the American Left by Christopher Lasch (Crossett Library Bennington College is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) / On right, Michel Foucault (Bettmann/Getty Images)