Some 28 years ago, I was sitting on a hot June day in the basement of a Paris conference center, surrounded by business executives from New York and France and a host of local media. Everyone was listening to New York’s then-mayor, David Dinkins, as he pitched Parisian firms on the benefits of locating their U.S. operations in Gotham. It wasn’t an easy sell. New York was beset by high crime, a steep recession, and racial division. Some in the New York media had even portrayed Dinkins’s trip abroad, which included stops in London, Lyon, and Frankfurt, as more of an opportunity to get away from the relentless bad news and criticism he faced at home than a marketing trip abroad. Dinkins, who died earlier this week at 93, didn’t do much to disabuse his Paris audience of that notion. He told the French executives, who treated him as a celebrity, “People keep saying, ‘Dave, you look like you’re having a good time.’ And I certainly am.”

Sitting in the audience, however, I got something of a different impression. I asked one French businessman at my table why he had come. He told me his firm had an office in New York, and he wanted to hear what the mayor had to say. When I asked him where his offices were located (midtown? the financial district?), he said, Fort Lee. I heard a lot of that during the trip—foreigners who wanted to do business in New York but had set up offices in New Jersey, Connecticut, or Long Island. Those that visited the city from Europe were worried by its decline. “I have to admit I still find the city quite a fearful place,’’ the owner of a London furniture company, Anthony Robinson, told me, even as Dinkins boasted that crime had fallen by precisely 4.54 percent from its dizzying, record levels.

Dinkins had been elected mayor two and a half years earlier in a racially charged campaign season, which saw him defeat the three-term incumbent, Ed Koch, in a Democratic primary and then best Republican Rudy Giuliani in a surprisingly close general election. The city had experienced a series of controversial crimes that year, including the beating and rape of a white, female investment banker in Central Park in April, and then the killing of a black Brooklyn teen, Yusef Hawkins, by white assailants in Bensonhurst. The primary campaign had been marred by accusations against Koch of racial insensitivity after he had criticized protesters who demonstrated against the Hawkins murder, calling their march provocative. Dinkins, by contrast, had praised the protests as in ‘‘the finest tradition in our country.’’ Supporters described Dinkins as “dignified and decent,” and he went on to defeat Koch by eight percentage points in a city yearning for racial peace. Dinkins carried 90 percent of the city’s black vote but also polled well among whites who seemed hopeful that tapping him as the city’s first black mayor would alleviate some of New York’s racial tensions.

But New York’s woes went well beyond the racial context of a handful of controversial incidents. Violent crime, which heavily victimized minority communities, had been rising steadily, and murders would eventually hit a record of 2,262 in Dinkins’s second year in office. The city lost more than 300,000 jobs in a recession that began during his term, and the sharp decline in the rate of growth of tax revenues led to a series of budget crises that Dinkins solved in part with big tax hikes and rising fines and fees on an already-overburdened business community. The emphasis on racial harmony that seemed so imperative during the campaign thus gave way to a general sense of desperation and yearning for leadership.

Some of this reflected a can’t-do fatalism that the soft-spoken Dinkins projected. He attributed the rise in crime at one point to aimless rage that resulted from racism and poverty that the police couldn’t control. “If we had a police officer on every other corner, we couldn’t stop some of the random violence that goes on,” he said to besieged New Yorkers after one particularly violent weekend. Though Dinkins is credited with increasing the size of the city’s police force, his first police commissioner’s solution was to advocate for cops to become community “problem solvers,” even as crime surged.

A hoped-for racial healing under Dinkins never materialized. Soon after Dinkins assumed office, a controversial activist who had campaigned for him, Sonny Carson, began a community boycott against a Korean grocery store after a local shopper said that she’d been accosted by owners who accused her of shoplifting. Though Carson and others carried signs that said, “Don’t shop with people who don’t look like us,” Dinkins refused for months to enforce a court injunction against the protests, which lasted nearly a year and a half. The city was also scarred by rioting in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn after a car driven by a Hasidic Jew struck and killed Gavin Cato, the child of Guyanese immigrants. The next day a group of 20 neighborhood men attacked and killed Yankel Rosenbaum, a 29-year-old Australian Jewish man who was studying in Crown Heights. Three days of rioting ensued amid criticisms that Dinkins was slow to increase police presence amid fears this might anger the community further.

Dinkins also sent mixed messages on the city’s budget, which undermined confidence in his stewardship. Soon after taking office, he handed out big raises to some city unions, but just months after granting those deals, his administration announced looming budgets deficits amid criticism from budget watchdogs. He levied record tax increases, which did little to encourage the business community. In a poll taken just months after I’d journeyed to Europe to watch Dinkins pitch foreign businessmen, 80 percent of New York small businesses said that they would not vote to reelect him.

New Yorkers in general were having similar doubts. After two years in office, Dinkins’s approval rating stood at a dismal 26 percent. In 1993, Rudy Giuliani narrowly defeated Dinkins, becoming New York’s first Republican mayor in 24 years and beginning an economic, fiscal, and civic revival of New York that lasted two and a half decades.

Dinkins and his supporters have argued for years that the city’s revival began under him, though the sharply different approaches that Giuliani took to everything from policing to taxing and spending to negotiations with city unions suggest otherwise. Even so, Dinkins, who used phrases like “gorgeous mosaic” to describe New York’s diversity, has always appealed to those who still believe that the city’s fundamental problem was not crime or an unsustainable budget or economy-stifling regulations, but racial injustice. The city’s current mayor, Bill de Blasio, who campaigned for Dinkins, said that Dinkins was a victim of that injustice himself. “Dinkins got a raw deal largely because of race . . . And he got a raw deal because he was not a loud, showy personality and he wasn’t always trying to claim credit.”

Today, amid calls to prioritize racial healing in an increasingly vitriolic political environment, the courtly and amiable Dinkins might offer us a few lessons on how to conduct oneself in public life. Sometimes, for instance, it was easier being on the opposite side of an argument with him than on the same side of one with Giuliani. I remember Dinkins approaching me at a reception for him in London and thanking me because the publication I then worked for, Crain’s New York Business, had praised his efforts in Europe after two years of otherwise dogged criticism of his mayoralty. We chatted like old friends, and I couldn’t help walking away hoping that this trip, with its emphasis that New York was open for business under his leadership, signaled a new direction. He was hard to dislike personally.

Alas, it didn’t signal any such thing, and New York needed a different kind of medicine, which it eventually got. Dinkins moved on to assume a sort of elder statesman role in New York. It suited him best.

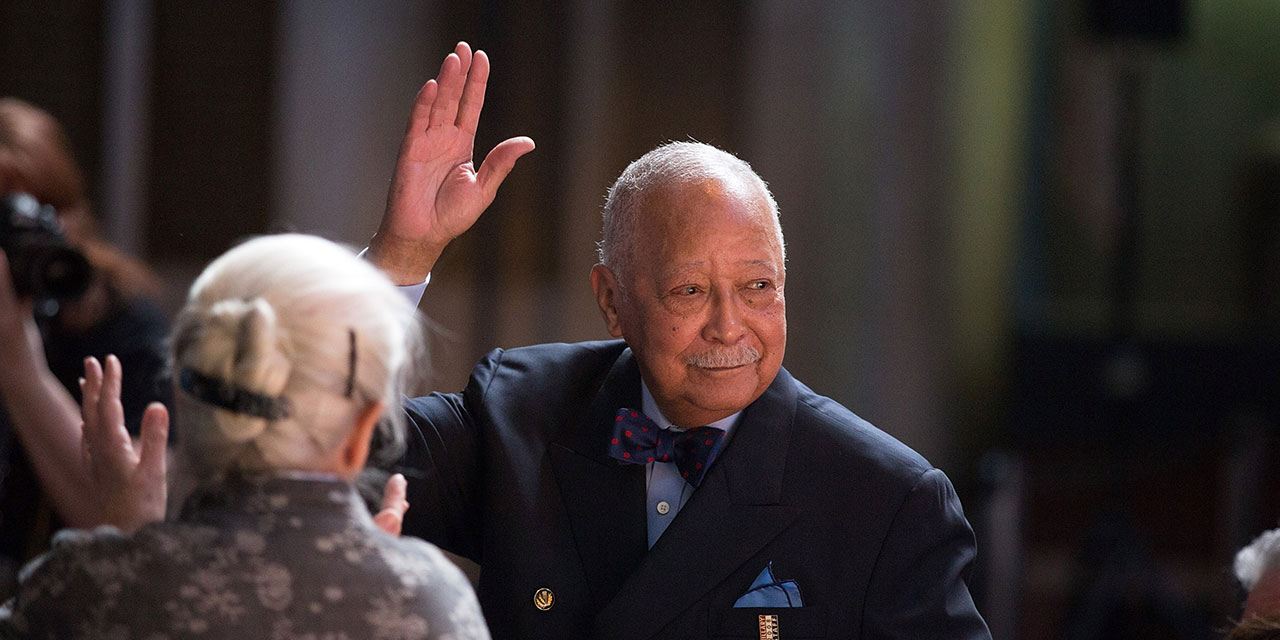

Photo by Kevin Hagen/Getty Images