Stefan Kanfer (1933–2018) was a contributing editor of City Journal for more than two decades, a best-selling author (he wrote brilliant biographies of Groucho Marx, Humphrey Bogart, and Lucille Ball, among numerous other works of nonfiction and fiction), and cultural maven. He was an effortless, punchy writer, covering topics ranging from the American musical theater to the Holocaust, from graphic arts to politics to his years at Time; and he was an invaluable colleague and cherished friend whom we miss deeply. When Steve died this past June, we had just finished editing an essay of his on the evolution of American retail. Thus it is with a mix of pleasure and sadness that we post here Steve’s final piece for us, “A Brief History of Shopping.”

—Brian C. Anderson

Not far from Interstate 95, the artery that cuts through New England, the SoNo Collection, a new mall slated to open in 2019, is rising in South Norwalk, Connecticut. Not so long ago, such an event would go unremarked. But that was then; this is Amazon.

One after another, the great names of retail are giving way to online sites. Caught in the tsunami, once-thriving companies have washed away, and with them thousands of sales and administrative jobs. The ubiquitous Radio Shack stores treaded water for a few years, but like the giants, they, too, have become victims of online sites. So have Staples, Payless, Michael Kors, Abercrombie & Fitch, and a host of other firms, formerly prominent, now unprofitable. And drowning alongside are the malls that housed them.

Credit Suisse recently predicted that by 2022, some 25 percent of U.S. shopping malls will fold. And this may underestimate the trend. Ron Friedman, a retail specialist at the advisory firm Marcus, indicates that the situation could be “more in the 30 percent range. There are a lot of malls that know they’re in big trouble.” That trouble began with the ascendance of the Internet, marking the fourth great upheaval in U.S. retail.

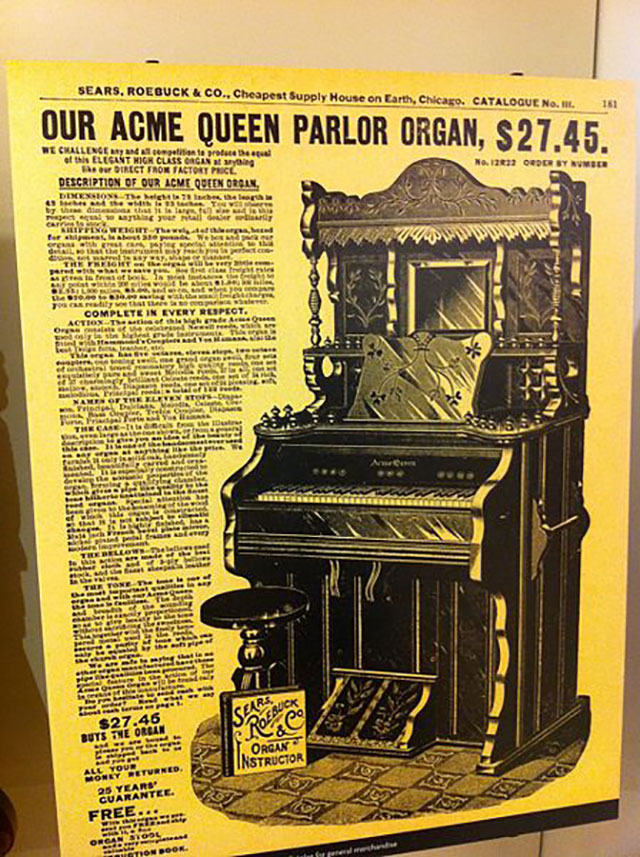

The first came a century and a half ago, with the emergence of the first important catalog, originated by two mail-order salesmen, Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck. In a predominantly rural America, visiting a major city required extensive planning and expenditure. Sears Roebuck & Co. eliminated the need for trips to the dry-goods and hardware store—to almost any store, in fact, except the grocery. Citizens in farming towns leafed through the company’s two-inch-thick publication—often referred to as a “Wish Book.” They daydreamed about items that they couldn’t afford and clothing models whom they would never meet. Then they selected the items that they had to have, sent in their money orders, and waited for the truck to arrive. It would appear in a few weeks—warp speed in those days.

Humorist S. J. Perelman grew up on a Rhode Island chicken farm. As he examined one of his parents’ old catalogs, fantasies came to mind. “No. 24810, a model known as ‘Exposition,’ is thus described: ‘Perfectly shaped and a fine fitting corset, equal to any installed at 80 cents. Price, $0.40.’ Could any late Victorian wolf, encircling his inamorata’s hourglass waist, ever have dreamed that the treasures in his grasp were packaged in forty cents’ worth of whalebone and cambric?”

Menswear included the standard overalls and boots, and also offered items that might have attracted the YMCA, but appalled the ASPCA: “Our $23.95 Broadcloth Professional Suit. Just the suit for ministers, physicians, and professional men”; for flashier types, there was “No. 4442: Fur Overcoats. $8.90 buys a regular $15.00 Spotted Dog Overcoat. Made from carefully selected Dalmatian pelts.”

Dry goods and tools took up large portions of the catalog, but there was always room for items devoted to the reader’s physical condition. “However remote Sears Roebuck’s customers may have been from the main depot in Chicago,” Perelman notes, “their health was safeguarded by a vast array of patent medicines and proprietary articles. Twenty close-knit pages of elixirs, specifics, boluses, capsules, chemicals, tinctures, pills and granules undertook to combat practically any malaise on earth.” Typical is No. G-3059—Dr. Chaises Complexion Wafers: “Highly recommended by the celebrated Madame La Ferris of Paris and many others. They are unequalled for producing a clear complexion and a plump figure.” Should the figure get too plump, there was No. G—4200: “Obesity Powders. These powders are recommended for and are very successful in reducing the flesh of corpulent people. Follow the directions and do not look for immediate results.”

Industrialization was to end the enchantment of the Wish Book. Cities grew in size and population as workers sought jobs in the burgeoning factories, plants, and sweatshops. This migration ushered in the Second Upheaval. With employment came wages, and with wages came a desire for the better life, and with that came downtown shopping sprees.

To provide room for the merchandise, and comfort for the buyer, a new kind of space emerged: the department store. Enterprising immigrants like Adam Gimbel and Bernard Bloomingdale once peddled underclothes and costume jewelry from a pak tsores (Yiddish for “bag of troubles”) in outlying regions. They consolidated their profits, and capped their careers by ruling over vast urban structures. These embodied a commercial e pluribus unum: under one roof, many shops.

Rowland Hussey Macy surpassed them all. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Macy enlarged his retail holdings until, in 1902, he could open an 11-story flagship store in Herald Square, just south of midtown Manhattan. Beneath his big top, served by newfangled wooden escalators, were emporia offering everything from automobile supplies to zwieback. Consumers might spend an hour—or an entire day—within Macy’s million square feet of market space, lunching with friends, ordering household necessities and personal fripperies, and returning home spent, in every sense.

Not to be outdone, a monumental Gimbel’s opened one block south, initiating a decades-long competition. Sometimes the feud was friendly, as in the 1947 feel-good film Miracle on 34th Street, when the giants are reconciled by a benign, white-bearded Kris Kringle. But most of the time, it was all-out war, with Macy’s ads booming “It’s Smart to Be Thrifty” and its hostile neighbor retorting, “Nobody but Nobody Undersells Gimbel’s.”

This gigantism affected most major cities. Los Angeles had the May Company; Chicago, Marshall Field’s; Boston, Filene’s; Dallas, Neiman Marcus; and Detroit, the grand behemoth Hudson’s, with 32 floors and four basements. For an extended period, these and other colossi ruled urban America, branching out until they opened satellites in just about every metro area. But like the dinosaurs of the late Cretaceous period, they were ultimately too big not to fail.

And thus began retailing’s Third Upheaval. After World War II, millions of veterans and their families traded the congested, expensive cities for the green and reasonable suburbs. For shopping, they no longer depended on buses and rail; they drove their cars to their destinations. To answer the suburbanites’ requirements, shopping malls arose. Traditional retailers, from high end to discount, from Macy’s and Sears to Dollar Stores and Toys“R”Us, hurriedly opened outlets at the new shopping centers. There was only so much disposable income to go around, however, and as cities began to deteriorate, their department stores became victims of declining sales and increasing pilferage. It was only a matter of inventory before they shut their doors for good.

At the same time, REITs (real estate investment trusts), begun in the Eisenhower era, allowed investors to back developers with relatively small infusions of cash. Using this new money, builders constructed malls nationwide. The majority were, and remain, “strip malls”—bulldozed, featureless areas near a main road. Customarily, they are the locale of a chain-store pharmacy, a bank, a few fast-food restaurants, a nail salon, and a dry cleaner. And customarily, they are the scar tissue of the American landscape.

But the grand commercial malls turned out to be something else entirely. The Outlets at Bergen County Center, for example, situated 20 miles from New York City, opened with 100 attractive stores within its borders. Similar malls sprang up around all major cities, from Seattle to Miami. The largest and most visited, from its debut in 1989 to the present, is the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minnesota. Sometimes derided as the Sprawl of America, it houses more than 400 stores, has 11,000 employees, and annually attracts 42 million shoppers—eight times the population of the mall’s home state. But like the monumental department stores of the past, it has become vulnerable to new disruptions. One is Islamic radicalism, which recently motivated a knife-wielding fanatic within the mall’s supposedly secure borders. The other is equally ominous for the future of this and every mall: Amazon.

Until the turn of the century, one of the most popular ad slogans of all time was the Yellow Pages line, “Let your fingers do the walking.” The implication was clear: customers didn’t have to wander from store to store; they could explore the phone book, call various retailers, and check prices before they went in to make their purchase. Now the Yellow Pages themselves have gone electronic, and fingers not only do the walking; they do the buying. Though many stores have learned the value of an online presence, Amazon has seized a monster share of the retail business.

A close look at the last 13 years shows how and why this company elbowed its way to the front. Back in 1994, an ambitious Princeton Phi Bete pulled up stakes at a Manhattan hedge fund and headed to Seattle, the hot locale for Internet venture capitalists. Jeff Bezos’s new outfit was going to be called Relentless.com—an apt moniker, considering what was to follow. But in the end, Bezos decided that Amazon, the world’s longest river, looked better on computer monitors.

Amazon began as a modest discount bookstore. Yet like its namesake, it wound through unexpected territories. Browsers were presently enticed with bargains in housewares, clothing, luggage, electronics, pharmaceuticals, comestibles, garden supplies, tools, toys, tablets. Name the items, and they were soon there online for consumers to see and evaluate before they submitted their orders with a few keyboard clicks. But Amazon did more than offer goods and services—it saw that they were dispatched and delivered, often in a matter of two days. Keenly aware of the American appetite for instant gratification, Bezos set up vast fulfillment centers (read: warehouses) around the country. (The one in Phoenix, for example, covers 1.2 million square feet—enough to contain 28 football fields.)

Thorstein Veblen’s concept of conspicuous consumption has given way to Jeff Bezos’s notion of continuous consumption. To that end, fulfillment-center employees are expected to move goods from miles of shelves, package them in cardboard boxes, and then convey them to loading docks—all within a matter of minutes. Each worker is closely supervised and measured for productivity; each must be able to lift up to 49 pounds, and to stand or walk across concrete floors for as long as ten hours a day. Collective bargaining is not Amazon’s thing; none of its warehouses is unionized. (The company is quick to point out that employees on the floor are generally paid between $10 and $14 per hour and that they receive health insurance and a 401(k) match of 50 percent.)

Still, at Amazon, nothing is written in concrete. Conditions are about to change dramatically. People will no longer be required to fill Amazon’s most repetitive and physically exhausting slots. The jobs will be performed by robots—there are already 100,000 of them moving around the fulfillment centers, with thousands more on the way. The company is also purchasing fleets of drones to turn same-day delivery into same-hour delivery. This suggests a cyborg-run dystopia coming to a site near you.

But that doesn’t seem to be the case. The New York Times reports that Amazon’s “eye-popping growth has turned it into a hiring machine, with unquenchable need for entry-level warehouse workers to satisfy customer orders.” Many of those workers will be replaced by machines, yes, but many more will move up in the company, assuming supervisory positions across the globe. (Amazon has warehouses in 14 countries.)

Which is why, when Amazon expressed the need for a new headquarters to supplement the nerve center in Seattle, U.S. cities frantically entered their bids. Mayor Bill de Blasio led the Hypocrites Day Parade, at once decrying ecommerce (“I have never bought anything from Amazon”) and boasting that any of New York City’s five boroughs would provide a good fit for the company. His Honor’s doublespeak makes Gotham a highly unlikely choice.

If Amazon’s growth continues at its present pace (it already makes up 43 percent of online sales), it will one day need a third headquarters, and then a fourth, and then. . . . Back in 2013, Bezos bought the supposedly unavailable Washington Post, causing tremors throughout the mainstream media. Earlier this year, Amazon acquired the high-end Whole Foods (often put down as Whole Paycheck), promptly undercutting prices and rattling the grocery chains. It recently inaugurated Amazon Maritime, a nautical subsidiary that will convey exports from the People’s Republic of China to the United States of America, making waves throughout the shipping industry. And it has begun to produce feature films for theatrical release and video streaming programs, unnerving Hollywood studios. Few areas are now beyond the company’s tentacular reach.

Naturally, not everyone is a fan. Perhaps the loudest critic is President Donald Trump, who bombinated that Amazon was a “no-profit” company that would “crumple like a paper bag” if it paid its fair share of taxes. He followed up this criticism on Twitter, announcing that Amazon “is doing great damage to tax paying retailers. Towns, cities and states throughout the U.S. are being hurt.” Actually, according to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Amazon, after years of stasis, is becoming quite a profitable enterprise: it paid $879 million in income taxes in the 12-month period ending in June. And it will be employing many more taxpayers and paying far more business taxes in the future.

But just what is that future? Will there be a fifth upheaval? No one can say—not Trump, not the market, not even Bezos himself. In the Sears Roebuck era, who could have foretold the department store? And in that epoch, could R. H. Macy or Adam Gimbel possibly have envisioned the day when Julia Roberts spoke for millions: “Show me a mall and I’m happy”? And what eupeptic mall builder could have predicted the Internet? The iPad? Cell phones? Amazon? When someone asked British scientist J. R. S. Haldane to depict the future, he threw up his hands. The infinite universe, he commented, “is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” The finite universe of retail, likewise.

Top Photo: jahcottontail143/iStock