According to polls, local government is the most popular form of government in America. A 2013 Pew survey found that 63 percent of Americans view their local government “favorably,” while only 28 percent approve of the federal version. As many policy experts and pundits see it, cities are models of government that work, in contrast with the dysfunction prevalent in state capitals and in Washington.

Despite their popularity, local governments in the United States are troubled. Americans may be disgusted with Washington, but they vote at much higher rates in national elections than in local ones. For example, only 26 percent of New York City’s registered voters (1.1 million) cast ballots in the 2013 mayoral election, compared with 58 percent (2.4 million) in the 2012 presidential election. Local political apathy has enabled some cities to become dominated by one party or even one interest group, skewing the political process and often encouraging extensive corruption and mismanagement of finances. As a consequence, many cities continue to struggle with fiscal distress, six years after the last recession ended. San Bernardino, California, drove itself into bankruptcy in part through lavish public-employee compensation. Detroit, a fiscal black hole, should have been taken over years before Michigan formally installed an emergency manager in March 2013. And even with a chief executive as hard-charging as Rahm Emanuel, Chicago seems completely overwhelmed by its debt and pension woes. Fans of local autonomy are hard-pressed to explain these and other failures.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

With many other cities facing imminent danger to their budgets and balance sheets, what may be needed is less local autonomy—and more state leadership. The most serious threats to city budgets—excessive debt, political dysfunction, and soft tax bases—are not going away anytime soon. It makes more sense to expect state, not city, officials to do what’s right when faced with local fiscal distress, instead of what’s politically convenient. To prevent more Detroits, state governments should rein in local officials’ ability to make bad fiscal decisions, by intervening early and forcefully when insolvency’s early warning signs begin to emerge. At least with fiscal policy, if we want stronger cities, we should support more state-imposed constraints on them.

Cities’ relationships with states differ from those of states with the federal government. American federalism is a constitutional framework of shared sovereignty between the national and state governments. The state/federal power balance has shifted a lot over time, generally to Washington’s advantage. Throughout the twentieth century, the New Deal, the Great Society, and the expansion of various rights claims (civil, environmental, and so on) led to a significant concentration of power at the national level. Nevertheless, as long as the Tenth Amendment remains in effect (“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people”), states possess constitutional rights that Congress, the president, and the Supreme Court must respect.

By contrast, cities go unmentioned in the Constitution, and they have no sovereign rights to assert against state encroachments. Legal restrictions on cities were very strong in the nineteenth century. As the Iowa Supreme Court Justice John Forrest Dillon put it in 1868, “municipal corporations owe their origin to, and derive their powers and rights wholly from, the [state] Legislature. It breathes into them the breath of life, without which they cannot exist. . . . We know of no limitation on this right so far as the corporations themselves are concerned.” In the eyes of the law, even the city of Boston, settled in 1630—decades before the charter for the Province of Massachusetts Bay was issued and 150 years before the Massachusetts state constitution took effect—was always considered a creature of the state.

The American tradition of self-government has always mitigated cities’ lack of legal sovereignty. Since the earliest Puritan settlers, Americans have been accustomed to managing many of their affairs locally. In the twentieth century, passage of “Home Rule” legislation broadened localities’ regulatory and spending powers. The old “creature of the state” doctrine was, in many respects, overturned, but the tension between state dominance and local autonomy remains. Policymakers tend to resolve the issue on a case-by-case basis, with neither liberals nor conservatives adhering to consistent stances.

Yet while local autonomy remains a cherished ideal, cities don’t always use their independence wisely—to put it mildly. On fiscal matters, in particular, cities (at times enabled by states) have often proved their own worst enemies.

Sometimes bad local fiscal decisions represent, in effect, perverse rejections of local autonomy. One primary cause of San Bernardino’s still-unresolved bankruptcy was its policy of computing public-safety employees’ compensation by a predetermined formula based on workers’ pay in much wealthier California cities—and not through negotiations with its own workforce. Thus, San Bernardino (median household income: $38,385) based its pay scale on those of Santa Clarita ($82,607) and Irvine ($90,585). San Bernardino’s leaders felt so strongly about abrogating their negotiating authority that they put the formula into the city’s charter. And voters are complicit. In 2014, they rejected a ballot initiative to eliminate the charter provision.

Saddled with crushing debt burdens amid uncertain economic prospects, many other cities could face fiscal distress in the years ahead. Over the past decade, Central Falls (Rhode Island), Vallejo and Stockton (California), Jefferson County (Alabama), and Detroit have gone bankrupt. At present, 18 Pennsylvania communities are enrolled in the Act 47 program for municipalities “experiencing severe financial difficulties,” and 18 Michigan municipalities operate under the terms of Public Act 436, the state’s Emergency Manager Law. In a 2015 report, New York State comptroller Thomas DiNapoli classified 44 local government entities as being “in some level of fiscal stress,” with 15 “in significant fiscal stress.” In April 2009, Moody’s assigned its first-ever “negative outlook” to the local government bond-market sector.

Cities’ fiscal health has improved somewhat since then; Moody’s has revised its outlook on the local sector to “stable.” But credit quality has not bounced back to prerecession levels. Recent analysis by PNC Capital Markets’ Tom Kozlik has found that Moody’s continues to cut government credit ratings at about double the rate that it did from 2002 through 2007.

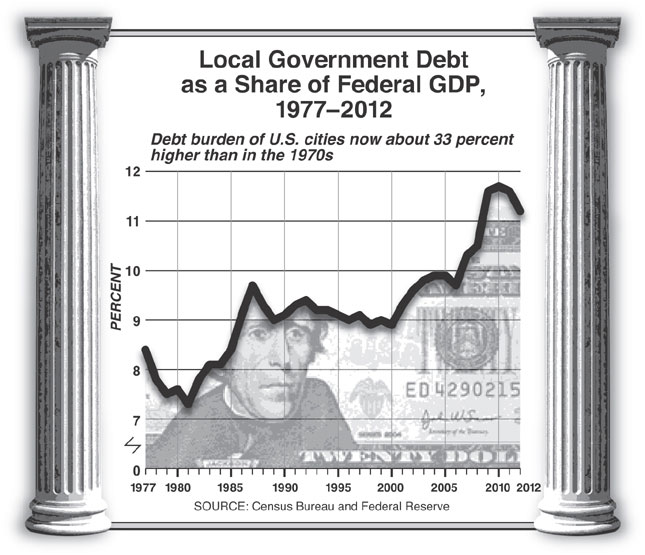

Local governments’ total outstanding debt stood at $1.8 trillion in 2013, the most recent year for which Census Bureau data are available. Expressed as a share of national GDP (11 percent), this sum is down slightly from its 2009–11 peak but still higher than at any other time going back at least 35 years. Cities’ retirement-benefits burden has been worsening rapidly. In a study published in January 2015, Stanford University’s Joshua Rauh found that ten large U.S. cities’ pension liabilities had grown by 40 percent since the end of the Great Recession—from $277 billion to $359 billion—despite 75 percent growth in equity values from 2009 to 2013 and a wave of pension-reform legislation. (See “Scary Pension Math.”) These elevated pension and bonded-debt figures suggest that the threat of municipal insolvency is greater than at any time since the Great Depression.

Compounding the problem of many cities’ extensive liabilities are relatively weak revenue bases. Nearly eight years after the last recession began, city revenues nationwide still have not returned to 2006 levels, according to a recent National League of Cities study. Among American cities, Detroit continues to stand out along several negative indicators, such as crime and unemployment, and the city has notoriously bled population (and hence taxpayers), from a 1950 peak of 1.8 million to fewer than 700,000 today. Detroit has lots of company: Baltimore, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Akron, Milwaukee, Scranton, and Buffalo have all lost population in every decennial census since 1960. St. Louis has actually hemorrhaged a greater share of its population than Detroit over the last six decades. Flint, Syracuse, Gainesville, Hartford, and Dayton suffer from poverty rates within 5 percentage points of Detroit’s. Many small and midsize cities remain at a loss as to how to revitalize themselves economically in the long-running aftermath of deindustrialization. Targeted tax relief (through industry- or place-specific incentive programs), rezoning business properties for residential use (or vice versa), sports stadiums and other splashy downtown megaprojects: these and other approaches have been unavailing, measured in terms of substantive gains in jobs and income.

The closest that struggling cities have come to devising replicable economic-development strategies are “eds and meds”—that is, replacing some of their lost manufacturing jobs through expansion in higher education and health care—and pursuing gentrification-friendly policies. Demand remains strong in education and health care; but in the years ahead, trends such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and hospital consolidation will accrue more to the benefit of large urban centers than to small and midsize cities. Likewise, while many downtowns look far more attractive now than they did 30 or 40 years ago (thanks, in part, to gentrification-minded tactics such as targeted tax-incentive programs), gentrification itself rarely makes a substantial impact on neighborhood income levels. In a 2014 study, economists Joseph Cortright and Dillon Mahmoudi found that, among the 1,100 census tracts in major metropolitan areas with poverty rates of 30 percent or more in 1970, only about 100 had seen their poverty rates drop below the national average by 2010.

Economic difficulties aren’t confined to small and midsize cities. The “global” status of a top-tier city like Chicago didn’t prevent it from accruing a multibillion-dollar debt. Big cities can make fiscally ruinous choices, too.

Why do so many cities and localities wind up running into financial trouble? Political paralysis—rooted in low levels of political participation, weak or sleazy leadership, and control by government unions—can keep cities of all sizes from gaining control of their balance sheets.

Among other things, political apathy facilitates union power. Teacher, police, and firefighter unions, which get their supporters to the polls and pour lots of money into local campaigns, enjoy a level of influence over local policymaking that, say, the National Rifle Association or Planned Parenthood could never dream of attaining at the national level. The University of California at Berkeley’s Sarah Anzia has found substantial pay premiums for teachers and firefighters in cities that hold off-cycle elections, where voter turnout levels are particularly low, meaning that it’s easier for unions to dominate. Even when staffing levels or compensation packages become patently unsustainable, many cities’ political systems remain incapable of fiscal reform because labor remains the sole meaningful constituency. For whatever reason, local voter outrage is in short supply.

The exchange of union political support for taxpayer-funded salaries and benefits from sympathetic officials is not only corrupt; it also poses a direct threat to municipal solvency because the vast majority of city budgets are weighed down primarily with compensation costs. (Were local chambers of commerce as influential as unions, cities would still be corrupt, but the fiscal risks would not be as dire.) During Vallejo’s 2008–11 bankruptcy, to take one example, police unions kept getting raises from the city council.

Conservative proponents of municipal autonomy rightly emphasize the role that state collective bargaining mandates have played in cities’ fiscal struggles. The problem with these mandates is not that they are handed down by state governments but that they empower government unions. In the three states with outright bans on collective bargaining in the public sector—Virginia, South Carolina, and North Carolina—local governments cannot let unions participate in formulating compensation packages and work rules. In this case, less local autonomy is clearly a good thing.

The case for why states should step in even more aggressively reflects a process of elimination. Cities in fiscal distress can’t be trusted to stabilize their balance sheets—there’s simply too little evidence of it happening. As for the federal government, its main option (other than bailouts) is bankruptcy, a legal process through which cities can break contracts and restructure their debt burdens. But while bankruptcy alters the legal landscape of debt and contracts, the political realities that fostered fiscal distress remain in place. Under Chapter 9, the same officials who drove their cities into insolvency continue to direct fiscal and administrative matters and have the exclusive right to propose debt-adjustment plans. This helps explain why, despite the central role that pension debt played in the recent wave of municipal bankruptcies, no city other than Central Falls has made significant pension cuts through bankruptcy.

Though their legal authority to break contracts is much less certain than federal courts’, state governments are better able to confront fiscal distress than any federal—or local—actor. True, states have undermined their standing as fiscal authorities of last resort by their own highly checkered record on budgeting and debt management. States’ use of financial gimmicks has been just as egregious as cities’, and their capital and retirement-benefits obligations are no less excessive. And the role of states in the debacle of interest-rate swap contracts that triggered the two largest municipal bankruptcies in American history—Jefferson County’s and Detroit’s—has been overlooked. It was state legislation, passed under the dubious justification of expanding localities’ fiscal flexibility, that brought the counterparties together in the first place.

But the logic for greater state control is inescapable. The risk of distress is much greater for cities than for states, whose tax bases are more diverse and growth outlooks brighter. No state has defaulted since Arkansas during the Great Depression; between 1950 and 2010, Michigan’s population grew by 55 percent as Detroit’s declined by 61 percent. Cities will run out of money much sooner than any states do; their dire fiscal fundamentals make distress not a question of if but when. Tough decisions will be necessary to forestall local insolvency. Distanced from local political pressures, state governments are more likely than local governments to make such decisions.

State officials must take the lead and deliver specific institutional reforms to restore municipal fiscal stability. Over the long term, substantive pension reform will reduce the possibility of distress down the road. States can and should restrict localities’ access to complex financial instruments. A simpler, less sophisticated municipal bond market will also be a less vulnerable one. No city has gone bankrupt from excess General Obligation bond debt.

The more challenging question is what to do about distress in the near term. Even if, tomorrow, all 19 million state and local employees were switched out of their debt-generating defined-benefit retirement plans and enrolled in defined-contribution plans—in which employer contributions are guaranteed but future benefits are not—governments would still be on the hook for trillions in already-promised payouts. In a recent Columbia Law Review article, NYU law professor Clayton Gillette argues for countering municipal distress by means of “an appointed, indeed dictatorial, takeover board” that would be “better positioned to resolve the underlying issues of fiscal instability than more democratic alternatives.” In Gillette’s view, a carefully crafted state intervention policy can do more to remedy distress than federal bankruptcy, federal or state bailouts, or broader grants of local autonomy. And state intervention is still fundamentally democratic. Not only was Rick Snyder twice elected governor of Michigan; he also gained 1,900 more votes in Detroit in 2014, after installing emergency financial manager Kevyn Orr, than he got in his 2010 campaign.

States can take over cities via control boards, such as were imposed on New York City following its near-bankruptcy experience in 1975, or through a Detroit-style emergency manager. Either mechanism can work, assuming that state officials have the will to empower their appointees to act with real authority and not just to offer advice and expertise. (It’s local officials who should be forced into an advisory role, at least until budgetary stability has been restored.) State appointees should be able to veto proposed contracts and budgets, reorganize city administrations, hire and fire top management, implement an austerity regime (hiring freezes and no new raises), and institute rigorous programs of financial reporting and analysis.

Such a program will require an oversight capacity to detect early warning signs of local fiscal distress. States should monitor indicators such as the use of one-time revenue sources, the accuracy of revenue projections, debt exposure, tax capacity, reserve and pension funding levels, housing prices, and unemployment rates. By publicly raising concerns about cities’ financial conditions early on, states can help strengthen the hand of reform-minded local officials and perhaps obviate the need for more drastic steps. For maximum effect, governors, who speak with the loudest voices on the state scene, should take the lead in oversight efforts, linking them to the threat of an outright takeover. In 2012, DiNapoli established a “Fiscal Stress Monitoring System,” but he has no power beyond the ability to shame fiscally unstable localities. Warnings of distress are more likely to be taken seriously by local officials, the media, and the public if they are connected to a serious possibility of the loss of local power.

For too long, state governments have cited reverence for local autonomy as an excuse to avoid taking dramatic action when cities face insolvency. But states need to step in, Caesar-like, earlier and more vigorously than they’ve been doing. Fiscal distress not only threatens a city’s ability to perform all basic municipal functions; it also threatens spillover effects, since the consequences of defaults and bankruptcies don’t respect local borders. Solvent neighboring communities may find their access to credit suddenly threatened by anxious bond markets. States must confront the tension between local democracy and their responsibility to ensure the welfare of all municipalities, including non-distressed ones.