Since early 2009, Wall Street has enjoyed the third-longest bull market in history. Catalyzed by super-low interest rates, the S&P 500 has risen more than 200 percent, helping inject life into portfolios that had suffered tough losses in the crash that had begun in late 2007. Among the beneficiaries were state and municipal pension funds, which the Great Recession had hit particularly hard, leaving many of the systems drowning in debt.

Yet the real news about the bull market may be how little these giant retirement systems have recovered. In July, with stocks climbing to a six-year peak, the Pew Charitable Trusts reported that state and local pension debt nationally had shrunk little since 2009. “The gap between the pension benefits that state governments have promised workers and the funding to pay for them remains significant,” the report observed. The situation only worsened as news began leaking out last summer that pension funds had notched mediocre returns for the fiscal year ending June 30, taking on even more debt. Then the market deep-dived in August, and Fitch Ratings issued a stark warning that public-pension funding “has barely improved since pre-recession highs.” A big reason: millions of government workers keep racking up new pension credits every working day.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Public-pension officials are now starting to admit that they’ve underestimated how hard it is to bounce back from the kind of precipitous declines in assets that result from major market downturns like the one in 2008 or the dot-com crash at the turn of the millennium, which first put many pension plans in the red. Nearly $100 billion in extra state and local taxes pumped into pension systems over the last seven years has had only minimal impact on the debt problem because governments owe so much—somewhere between $1 trillion and $4 trillion, depending on how liabilities are calculated—that debt payments simply overwhelm taxpayers’ new contributions. Most of the pension reforms that states and cities have enacted, meantime, are failing to provide the savings that politicians had touted; courts have blocked other needed changes.

With many state and local budgets under intensifying pressure from retirement costs, politicians keep proposing more new taxes to bolster pensions. Absent some startling development—like an even bigger runaway bull market—this crisis will keep worsening, forcing far-reaching rewrites of state and municipal budgets for years to come.

States and localities began creating pension systems for their workers in the early twentieth century. For a time, they proceeded cautiously. New Jersey, for example, instituted a pension system for teachers in 1919, pledging that it would be “established on a scientific (actuarial) basis,” so as to avoid the fate of an earlier worker-funded system that had gone bankrupt. California approached the idea of a public employee-retirement system with similar prudence. A 1929 state commission studying the idea warned: “An unsound system is worse than none.” Initially, the new fund, established in 1932 as the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), aimed to replace about half the annual income of a worker retiring at 65, at a time when most retirees could expect to live just a few years longer. Because its goals were modest, California required the fund to limit its investments to secure government securities with a guaranteed return.

America’s post–World War II economic boom loosened these restraints. As public workers gained the right to form unions that lobbied and bargained for higher compensation, states started to introduce expensive new benefits. California added Social Security to worker retirements in 1961, for instance, and then supplemented pensions with automatic cost-of-living adjustments in 1968. In 1970, it lowered the retirement age to 60. To help pay for the largesse, the state, beginning in the 1960s, let CalPERS start speculating in real estate and stocks—riskier bets but with potentially higher returns than government securities. Over time, California raised the amount of assets that the pension fund could put into such investments. Other systems eventually followed suit. In 1999, South Carolina, facing pressure to capitalize on the 1990s market boom, became the last state to permit its retirement system to invest in stocks.

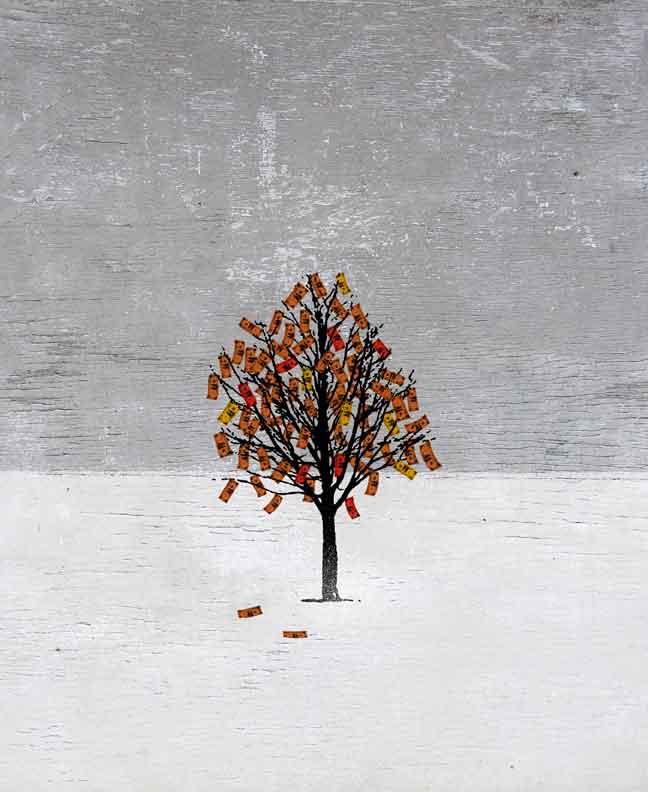

The new investing strategies brought substantial risk to pension funds—and to taxpayers. Back in 1970, the New York State Retirement System projected a modest 4.87 percent annual investment gain, a goal achievable simply by buying government-guaranteed bonds. That made sense in a state with a constitution that explicitly guarantees government pensions (a defined-benefit system, as it’s called), meaning that taxpayers are on the hook for any shortfall. But legislators discovered that they could pad pension benefits, without contributing much more up-front tax money, by allowing retirement funds to project much higher investment returns—and then invest more aggressively to try to achieve them. New York inflated its expectations for annual market gains to 7.5 percent in the early 1980s, and kicked them up again, to a heady 8.75 percent, by decade’s end. Public-worker pension benefits rose fast over the same period, hitting an average of 125 percent of an employee’s after-tax earnings during his final years employed. As a 1988 New York Times editorial complained, “The legislative habit of raising pensions is as hard to kick as cigarettes.”

These trends remade the financial architecture of many state and local pension funds. Whereas retirement plans once expected that more than half the money they’d need to pay benefits would come from government and worker contributions, states and municipalities increasingly came to rely on fat market returns. Since 1984, investment earnings have accounted for 62 percent of government retirement-fund revenues, according to a study by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators. Contributions by government employers (that is, taxpayers) constituted 26 percent of revenues, and contributions by workers just 12 percent.

The bull markets of the 1990s and mid-2000s helped foster the illusion that government could fund rich benefits at little cost to itself or to workers. From 1993 to 2007, annual contributions by state and local governments into pensions increased from $35 billion to $73 billion—a compound annual growth of slightly more than 5 percent—while worker contributions grew at a similar rate, from $16 billion to $34 billion. Thanks to robust investment gains, however, the assets of the funds exploded, rising from $910 billion to $3.3 trillion.

Rather than preserve this bounty, politicians used it as an excuse to hand out yet more new goodies to retired workers—and gave themselves holidays from contributions, to boot. Even as the 1990s bull market collapsed, New Jersey passed 13 separate benefit enhancements between 1999 and 2003, piling billions of dollars in new obligations on the pension system. In 2000, the well-funded South Carolina pension system lowered its teacher retirement age to 58 from 60, costing $1.8 billion in extra benefits. The state then approved a series of cost-of-living adjustments from 2001 through 2004 that added another $900 million in obligations. In 2000, just as the market was turning down, New York State and City also increased cost-of-living adjustments to pensions, adding $700 million a year to state pension costs and $400 million annually to city costs. Both state and city also began allowing workers with at least ten years of seniority to forgo payments into the system. Government unions and members of the board of CalPERS, the nation’s biggest pension fund, lobbied new California governor Gray Davis in 1999 to let workers “share” in the bounty from the 1990s market surge. The state legislature rushed to expand pension benefits, with some categories of workers receiving pensions equal to 90 percent of their final salary, plus annual cost-of-living adjustments—a scenario that helped California’s retirement system go from a surplus to $42 billion in the red by 2003. The notion of “sharing the bounty” helped cause an even bigger fiasco in San Diego, where the pension system imploded. Brought in to investigate, former Securities and Exchange Commission chairman Arthur Levitt blasted the common practice of considering strong investment returns as spare money to shower on workers. “Designating earnings in excess of 8 percent as ‘surplus&rsqo; made it look as if the City could grant additional benefits without providing a funding source for them. This impression was (and is) misleading,” Levitt concluded.

That politicians were willing to give away this money so quickly—and pension bureaucrats often went along without major objections—suggests that officials misunderstood the vulnerability of retirement systems based disproportionately on high investment returns. They should have known better. Recall what took place a decade and a half ago. After five consecutive years—from 1995 through 1999—when the S&P 500 advanced by at least 21 percent annually, the market, hit by the bursting of the dot-com bubble, registered three years of losses, leaving it 41 percent lower at the close of 2002 than at its peak two years earlier. The effects on pension funding were startling. Colorado’s funding level for its state-employee and local teacher-pension system dipped from 105 percent of assets on hand to just 75 percent by 2003; the state went from having zero unfunded pension debt to $9.9 billion in liabilities. Arizona’s state system, which boasted a hefty surplus in 2000, took longer to bleed red; but by 2006, it owed $4.6 billion. South Carolina, nearly fully funded in 2000, had accumulated some $5.6 billion in unfunded pension debt by 2004. Cities that managed their own pension systems fared poorly, too. Houston’s system, 91 percent funded at the close of the 1990s, had accumulated $1.8 billion in debt by 2003. Chicago’s municipal pension fund, 94 percent funded in 2000, slumped to 79 percent funded within just three years. In all, by 2003, government pensions were $233 billion in debt, according to Pew Research.

Governments have made little progress getting their funds back in the black since then, especially after the 2008 financial crisis hammered stocks again—even though investment gains averaged in the double digits for eight of the years since 2003, including increases in the S&P 500 of 29 percent (2003), 27 percent (2009), and 32 percent (2013). Yet pension debt has now swollen from $233 billion to an estimated $1 trillion (by conservative measures). All but a handful of state systems have higher unfunded liabilities today than in 2003. Using states’ own data, Pew estimated that the average funding in 2013 (the last year for which complete data are available) was just 71 percent, compared with 88 percent in 2003. Though states did register double-digit stock-market gains again in fiscal 2014, which have yet to be reflected in their annual reports, the fiscal year that ended on June 30, 2015, brought below-average returns. And now pension funds must contend with the market slide that began last August.

All this points to a future in which government pension systems, having lost so much money, can’t climb fully back from market declines before another one hits—an investment version of one step forward, two steps backward, resulting in steeper and steeper underfunding, from which recovery will be increasingly difficult, if not impossible.

To understand the full magnitude of the pension crisis, focus first on the missing money, something many journalists covering budget issues don’t do. Public-pension systems often describe their status in terms of how much funding they have available to pay for future debts. But it’s the money that’s not there that’s most important. Right now, government pensions are missing, on average, 25 percent to 30 percent of the money that they’re supposed to have—a devastating situation for a system designed to pay most of its benefits from investment returns. The missing money isn’t at work in the market, so no matter what returns a fund’s managers achieve, the gain on nothing is always zero. After a major downturn like 2008—pension funds typically lost a quarter of their assets—retirement systems have a lot less money to invest. And that limits the size of any bounce-back gains. It’s basic math.

For public pensions, though, the math gets worse because workers are earning new benefits all the time, and those get piled on to the debt associated with market downturns. Consider the reckoning in Utah, one of the nation’s best-funded pension systems at the time of the last market crash. After the 2008 slump, the state’s assets plunged 22.3 percent, and critics, led by State Senator Dan Liljenquist, began lobbying for reforms. Then the system’s returns rallied the next year by 13 percent; reform opponents argued that investment gains would solve the underfunding problem. But a state-commissioned study showed that the 2009 recovery was barely enough to keep the pension system from going deeper into debt: the system had to earn 7.75 percent yearly just to pay for workers’ new pension credits, which consumed much of 2009’s market return. The remainder went to pay off the interest on the debt that the state had accumulated. Utah, the study concluded, would have to average double-digit investment returns annually for 20 years to recover from 2008 via the market alone. That sobering scenario prompted substantial changes to the system, including a law capping taxpayers’ liability for pensions at no more than 10 percent of worker salaries—12 percent for public-safety workers. “One year of bad returns blew a 30 percent hole in our pension system,” Liljenquist observed. That was especially disturbing in a state that had always “put in every penny we were supposed to,” he noted.

Too often, the public officials overseeing pension systems aren’t forthright about this inexorable dynamic, perhaps recognizing that taxpayers might get more serious about reform if they realized how tough recovery would be. Pension funds produced mediocre investment returns in the last fiscal year—averaging about 3.4 percent, according to Wilshire Consulting—well short of the median investment target of most plans, which is now 7.69 percent, meaning that plans took on considerable new debt. But that’s not the way some states described their results. The Maryland pension system released a statement in July noting that the pension fund had returned just 2.68 percent for the year, yet the state’s treasurer struck a cheery tone: “Over the last five years our average return has been closer to 9.4 percent, a much more relevant measure of the overall health of our investment portfolio”—neglecting to point out that Maryland’s system has less than 70 percent of the assets it needs to pay its workers, so that even an above-average investment gain is barely adequate. Maryland pension debt—$18.6 billion in 2009—now stands at about $21 billion, notwithstanding the multiyear investment gains that its officials trumpet.

Pension officials contend that they’re trying to address the pressure on investment results by requiring more contributions into their systems, mostly from taxpayers, whose annual contributions into pensions have more than doubled over the last decade, reaching $121 billion, according to the Census Bureau’s yearly survey of government finances. In South Carolina, for instance, taxpayer contributions to the five funds that make up the state’s retirement system increased over the decade to $1.14 billion, up from $640 million. In Arizona, they jumped from $318 million to $966 million, while in New York State they rose to $6 billion, up from $3 billion.

But total pension debt across the United States exploded by about $670 billion during these years. Many state and local pension systems owe so much that their debt is substantially greater than their government’s entire annual tax haul. Governments have thus resorted to crafting pension-repayment plans that stretch out 20 years, and sometimes even 40 years—in other words, paying off the debt from a single bad year like 2008 over a period of decades. Seventy-five percent of pension plans have amortization schemes longer than 20 years, and 44 percent stretch 30 years or more, a 2014 Society of Actuaries study found. These payback agreements violate a basic principle of pension accounting: that a retirement system should aim fully to fund a worker’s pension obligations before he retires. In many states and localities, actuarial tables show that the bulk of current workers will retire in less than 20 years, which means that governments will have to keep funding pensions after many current employees stop working. At the same time, governments will need to begin funding the new benefits earned by the retired workers’ replacements—a huge double burden on future taxpayers. And these long amortization plans make it exceedingly likely that pension funds will experience other major market drops before they’ve paid off the damage from the previous ones.

Pension funds create the greatest strain on budgets when the economy is weakest. Stock-market downturns, which deplete pension-fund assets, are usually followed by economic woes that squeeze government revenues, making it difficult for states to find additional pension funding. The July Pew report shows that only 20 states made their full annual required contribution into their retirement systems in 2013, up from just 17 states in 2012. The problem began when state tax revenues dropped by 8 percent, or $64 billion in 2009, to $710 billion, and then declined again the next year to $705 billion; they didn’t rebound to 2008 levels until 2012. Even by 2013, state tax revenues had reached only $847 billion, a meager 1.7 percent compounded annual increase since 2008. Meantime, states also had to deal with soaring Medicaid costs and rising health-care premiums for their workers, as well as higher welfare payments and fiscal strains on their unemployment systems as joblessness spiked. Many states’ greater pension contributions represented a big commitment that was painful to pay—but not nearly enough to satisfy voracious pension funds.

Pensions have also had trouble recovering because local reforms have proved inadequate or wind up gutted by courts. Both Connecticut governor Dannel Malloy and New Jersey governor Chris Christie declared victory in enacting pension savings in 2011, though critics warned, accurately, that their states’ pension systems would remain extremely costly. Jersey’s pension payments, only $1 billion in 2012, must rise to $4 billion by 2018—in a state with only a $33 billion budget. Christie has since proposed a much more extensive, money-saving overhaul of Jersey’s retirement system, but he’ll have trouble getting it passed, after proclaiming that the state had solved its pension woes.

Connecticut’s situation is equally precarious. The state has seen pension payments, $900 million back in 2012, rise to $1.5 billion. That already-huge sum is expected to increase to $3 billion by early next decade and then to as much as $6 billion by 2030. Malloy has now proposed a controversial plan to split the system into two funds: one containing the pensions of new workers and carrying little debt; and the other with older workers’ pensions, which the state would pay for out of its annual budget on a pay-as-you-go basis. This would save the state $8 billion over the next decade but ensure the need for huge payments down the road as the unpaid debt piles up.

State courts or politicians failing to follow through have undermined reforms in other locales. An Illinois Supreme Court verdict invalidating extensive 2013 reforms will cost the state some $145 billion in tax revenues, which will have to be pumped into the pension system over 30 years, according to a study by the Civic Committee of Chicago. Earlier this year, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled that government workers in that state were guaranteed annual cost-of-living adjustments to their pensions, after the state tried to reduce them. The ruling will cost the state an additional $345 million a year. In some cases, too, politicians have abandoned reform efforts before they’d made any real progress on reducing pension debt. In Maryland, former governor Martin O’Malley pledged in 2011 to send $300 million a year in extra money into the pension system, but, looking to pay for worker raises in 2014, he cut that amount to just $100 million.

Defenders of the current system—including pension-fund administrators, union leaders, and some politicians—argue that, unlike companies with pension plans, governments don’t go out of business, so they’re justified in depending disproportionally on investment gains for their retirement systems. After all, they have an unlimited amount of time to make up any shortfalls. Over time, this notion became so sacrosanct that, in 2009, the Montana retirement plan even began warning actuarial firms, vying for the right to provide it with services, that if they used more fiscally conservative valuations, they shouldn’t even bother submitting bids. Pensions & Investments, an industry trade publication, reported that “rumor has been around for at least a year that other public systems have been engaging in similar threats,” which the publication referred to as “intimidation.”

Such opposition, however, has finally begun to wilt—albeit slowly—as the scary pension math becomes unavoidable. Recognizing that they’ve overshot in their estimations, pension funds have been lowering projected future rates of return. They now predict annual average gains of 7.69 percent—still high, but down from 8 percent in 2008, and the lowest average rate of projected investment return since 1989.

Some industry leaders are pushing for even lower returns. In 2012, New York City’s retirement system, one of the nation’s largest, began a long-term process of cutting its projected returns from 8 percent to 7 percent, thanks to pressure from then-mayor Michael Bloomberg, a Wall Street veteran who called the city’s assumptions “indefensible.” CalPERS has already reduced its projected investment-return rate to 7.5 percent; staff members have told the fund’s board that they want to reduce the return rate eventually to just 6.5 percent, so that they could cut investments in volatile stocks and pour more money into conservative instruments. The staffers realized that it was far harder to cushion assets invested in stocks from market dives than pension bureaucrats had previously acknowledged.

Even more telling, the CalPERS staffers seemed to accept a principle that private-pension funds have long acknowledged: once a pension fund gets too indebted, it may never recover. “CalPERS told city finance officials that if its investments drop below 50% of the amount owed for pensions, even with significant additional increases from taxpayers, catching up becomes nearly impossible,” the Los Angeles Times reported last August. Or as an investment manager recently told the New York Times, “It’s almost mathematically impossible to close the gap.” While the CalPERS pension fund itself is currently about 75 percent funded, at least using its own accounting standards (critics contend that its funding is actually lower), a growing number of public-pension funds are approaching the treacherous 50 percent level, and a few are already there, including the pension systems in Connecticut and Illinois. More cities, towns, and school districts—which have even less financial flexibility to deal with debt than states—have gotten there, too. Chicago’s police and fire pension funds, for example, are only about 35 percent funded. A recent study found that 25 municipalities throughout Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia and Scranton, are less than half funded.

An investment move toward less volatility will make fund finances more predictable and improve chances of avoiding another 2008-like pension-funding meltdown. Still, reducing risk does nothing to slash the $1 trillion or more in debt that pension funds have already saddled themselves with. Instead, by projecting lower gains, retirement systems will have to ask taxpayers to ante up even more to pay down their debt. How governments will afford this isn’t clear. New York City’s annual pension contributions have risen from $6.7 billion in 2010 to $8.7 billion in 2014, and will keep increasing for years as the city slowly cuts its rate of predicted investment return. CalPERS is already in the midst of a six-year plan to require California governments to boost contributions to the pension fund by 50 percent. Constrained budgets will get even further pinched.

Taxpayers should expect to suffer even more. Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel recently proposed a $543 million property-tax increase to pay for pensions. Illinois’ Cook County, meanwhile, increased its sales tax 1 percent to raise half a billion dollars for its pension shortfall. The sales tax in Chicago—if one combines the county, city, and state levies—now stands at 10.25 percent, the nation’s highest. In Pennsylvania, where hundreds of school districts have seen teacher-pension costs skyrocket, 164 districts asked the state for permission last year to raise property taxes above Pennsylvania’s 2.1 percent cap. Each one cited higher pension costs as the primary reason. In 2014, West Virginia gave its cities the right to impose their own sales taxes to help pay down the pension bill. Other tax increases are in the works, as government unions and their allies lobby for more funds to bail out pensions. Our Oregon, a union-backed group, is sponsoring ballot proposals to hike taxes $2.6 billion to alleviate a state budget crunch driven by rising pension and health-care costs.

In California, unions are working on an initiative that would make Governor Jerry Brown’s temporary 2012 tax increases, passed via Proposition 30 and set to expire in 2018, permanent. About half the annual $6 billion from the Prop. 30 increase was supposed to go to school districts for more classroom spending, but the state’s teacher-pension fund has sharply increased required contributions from local districts. As those higher costs phase in, they’re consuming most of the Prop. 30 education money—one reason that the unions want the taxes to become permanent. Recently, a panel convened by Los Angeles schools superintendent Ramon Cortines claimed that the district could face bankruptcy once the Prop. 30 taxes expire, due to rising pension and health costs and shrinking enrollment.

Taxpayers and reform-minded politicians should demand greater cost savings before pension systems wind up so indebted that the cost of bailing them out eviscerates other government services. Among the biggest priorities should be eliminating the open-ended liability that defined-benefit pension plans generate by promising workers rich, guaranteed benefits based on their final salaries, which taxpayers must finance when the market fails. Utah, to take one salutary example, has created a new defined-contribution plan, in which the state would contribute the equivalent of 10 percent of worker salaries every year into individual pension accounts, and workers would receive a pot of money when they retired, based on the contributions plus investment returns. If, instead, workers choose to remain in Utah’s defined-benefit plan, the state now makes them, not taxpayers, responsible for contributions exceeding 10 percent of salaries. Other states, like Rhode Island, have created hybrid plans with modest defined benefits, topped by 401(k)-style private-pension accounts. About 7 percent of government workers with pensions now enroll in these hybrid systems, which reduce taxpayer risk.

Taxpayers should also demand substantial changes to the way that states and cities dish out benefits and determine the crucial parameters that govern pension systems, including actuarial standards. Pension-system bureaucrats and board members should be banned from lobbying for higher benefits for workers, as the CalPERS board has done in California. The pension-system overseers’ job is to manage the system effectively and protect worker assets, not engage in advocacy. As much as possible, too, taxpayers should seek to take key decisions out of the hands of politicians, who’ve too often proved willing to use pensions to purchase votes from workers. The Society of Actuaries has proposed that government pensions set projected rates of return based on a combination of long-term forecasts of market performance. In a 2014 study, the society determined that, using such a formula, the average projected rate of return of funds would be 6.4 percent—well below current estimates.

The biggest impediment to serious reform has been the notion that a few good years of investment returns, combined with some additional contributions, will solve most pension underfunding. This simply isn’t true, and taxpayers need to recognize it now. If they don’t, they could wake up soon to find their governments swamped with massive debt—and themselves holding the bill.