Lviv, Ukraine

It’s a huge, hangar-like building, disused and decrepit, on the outskirts of Lviv. But for Mykola Piddubnyi and his colleague Irina Gavrilova, the local entrepreneur’s gift was a godsend, allowing them to move their expanding wartime supply operation out of Gavrilova’s tiny apartment. The day I visited, there were dozens of wooden pallets spread out across the big space: one cluster—maybe 40 cardboard boxes—for baked goods, another for large plastic buckets filled with dumplings, still other areas for canned food and toiletries, even a pallet piled high with crutches and wheelchairs.

But Gavrilova guided us past all that to the area that meant most to her, with the boxes she and a team of friends and relatives pack every day for soldiers serving on the front lines. Unlike the other boxes in the warehouse, destined mostly for civilians, each of these cartons was an act of love: a hand-picked mix of items to sustain a soldier for a week to ten days. Canned meat, dried soup, pasta, sauerkraut, cookies, cigarettes, even toothpaste and toilet paper: the contents varied from box to box, each packed a little differently, with an unmistakable human touch.

Doesn’t the government provide food for fighters, I asked? “Not always,” said Piddubnyi. “It’s hard to get to remote, rural Donetsk. When I served there in 2015, we drank from puddles and ate frogs.” So this time around, people like Piddubnyi and Gavrilova are helping, doing whatever is necessary to support the war effort.

I visited Lviv in early April, just as the main focus of the war in Ukraine was shifting closer to Russia, from the central Kyiv region to Donbas in the east. Once an important medieval city and later an outpost of the Austro-Hungarian empire, Lviv had hardly been touched by the Russian invasion. Still, even as the fighting raged more than 800 miles to the east, it was clear to a visitor that this was a city at war.

Traffic in and out of the center snarled at military checkpoints. A curfew emptied the streets at 10 p.m. On my first night there, an air-raid siren sent me racing to the basement of my hotel. According to local estimates, hundreds of thousands of what migration experts call “internally displaced persons” (IDPs) had swelled the population of the city by more than 50 percent.

But even more striking, and arguably a more consequential change, was how the overwhelming majority of Lviv residents had put their lives on hold, repurposing whatever they did for work and reorganizing their days to bolster the war effort.

“Most people I know have dropped everything,” said Anna Swanson, a former real estate manager now focused on humanitarian assistance. “They’re using their own time and their own resources to support Ukraine.”

The city’s largest art museum had postponed events and put its paintings into storage, reinventing itself as a giant warehouse for humanitarian supplies. A policy-research nonprofit had suspended its work and converted its elegant townhouse office into a recruitment center for Territorial Defense militia. The city tourist agency was serving as a media hub, supporting foreign journalists arriving to cover the fighting.

White-collar, blue-collar, young and old, individuals and organizations, public and private: to call these efforts “civil society” hardly seemed to capture their scope or scale. This was an entire city mobilized to do its part to win a war.

“There are no bullets whistling by us, no missiles or explosions,” explained Roman Andreiko, co-owner of the nation’s largest TV news channel. “But this is also the front line. Who can say that what we’re doing is less important?”

Nothing captured the city’s transformation more vividly than a visit to the Lviv National Art Gallery. Like much of the Lviv war effort, the revered state-run institution was now devoted to logistics: collecting and shipping supplies to parts of the country cut off by Russian bombardment.

Three floors of a former cultural center had been emptied and divided into what staff called “departments”: separate rooms for mattresses, blankets, clothes, groceries, baby food, hygienic products, medical supplies, and electronic equipment. Volunteers scurried in and out. Some were unloading boxes of donated goods arriving from abroad. Others were sorting items into giant piles and repacking them in new boxes to be carried out to waiting vans, where still other volunteers stood ready to transport the supplies.

Museum director Yuriy Viznyak, a career civil servant, told me that he made the decision to convert the gallery on the war’s first day. “Many people I knew were leaving the city, heading for Poland or Hungry,” he recalled. “But I made the decision to stay. Even then, I believed Ukraine would win, and I had to do my part.”

Since then, the center has received more than 20,000 requests for help—from local municipalities, hospitals, military units, nonprofits, and individual IDPs as far away as Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Zaporizhzhya, a full day’s drive to the east. Museum staff compile requests and keep a running list of necessary items. On the day I visited, dried meat and sausage topped the foodstuffs list. Razors were top priority among household items. The director wanted protective military equipment—helmets and bulletproof vests.

Impressive as it was, Viznyak emphasized, the museum warehouse is only one hub of a much larger supply effort: a vast, decentralized web of individuals and organizations in Lviv, some working together, many operating independently.

Other supply depots, public and private, were springing up around the city. The museum’s pickups and deliveries were handled by someone else—independent teams of volunteers with their own trucks and vans. Alongside supplies shipped in from abroad and money wired from across Europe, the director singled out one local elderly woman who had recently delivered three pillows. “We have more requests than we can handle,” he explained. “But thankfully we’re not working alone.”

Anna Swanson also made the decision to upend her life on the first day of the war. Born in Ukraine, she had spent more than a decade in the U.S. before returning to the region five years ago. Before the war, she made a living helping to restore and manage rental properties in the historic center of the city. The day after the Russians invaded, she drove to the border with a car full of blankets and warm clothing for the refugees, mostly women and children, streaming from Ukraine into Poland.

“Big organizations move slowly,” she explained, “and in those first days, it was just ordinary, random people like me.” But things were constantly changing, and within days, there were dozens of groups providing relief on the border—humanitarian operations, large and small, many of them organized abroad. So Swanson expanded her scope, buying humanitarian supplies in Poland and delivering them inside Ukraine.

Then, a few weeks later, she saw that many other groups were doing that, too, and she refocused her efforts again. “The war doesn’t stand still,” she explained. “What’s needed changes every day. You identify the need that day or that week, and you reorganize to do it.” Her new mission: buying medicine in Poland and delivering it to hospitals in Ukraine.

The new operation supplies both military and civilian hospitals. What’s missing is often fairly basic: atropine for surgeries, insulin, adrenaline. Other facilities lack rarer or perishable medicines. Ukrainian doctors write the prescriptions; there are no barriers at the border. Swanson’s priority is hospitals treating medical casualties, and she and her team go wherever they can help—to Kyiv, Kharkiv, Krematorsk, and deep into the Donbas region.

The operation has grown rapidly into more than Swanson can handle by herself. But it hasn’t been hard to find help. She called friends, who called friends, who called other friends, and before long, she had a team of about ten volunteers—some driving, some loading and unloading, many of them chipping in their own money to buy supplies. There was no formal organization, just a common cause and a shared sense of urgency.

Like many similar ad hoc networks that have sprung up in Ukraine and in surrounding countries flooded by refugees, Swanson’s network is built on trust—members are all friends of friends, even if they don’t all know one another. People communicate mostly virtually, on an instant-messaging platform. Volunteers take on whatever roles they think they can handle. They do what they can for as long as they can, and the network grows and shrinks, adapting to cope with whatever is happening on the ground.

The challenge, faced eventually by almost all these small groups, is funding—money to pay for supplies, whether in Ukraine or abroad. In Swanson’s case, the solution was an American-led, Kyiv-based nonprofit, Help Ukraine 22, that raises money in the U.S. to support humanitarian relief inside Ukraine.

The operation is an offshoot of a for-profit business—a small government-relations consulting firm—operating in Kyiv for more than a decade. Like everyone he knew, owner Brian Mefford made the decision to pivot on the day the Russians invaded, switching from paid consulting to humanitarian assistance. The new nonprofit raised just under $1 million in the first seven weeks of the war, much of it on Wall Street and among Mefford’s friends in Republican internationalist circles.

At the beginning, the group’s main focus was evacuations: driving people who wanted to leave Ukraine out of the country. But like Swanson’s smaller, informal group, Mefford’s organization has evolved, and it now works primarily to provide medical assistance.

The operation relies on leverage: multiplying the power of the money it raises by investing shrewdly and enlisting others. Mefford and a small core team drive some supplies across the border themselves. “But if others can do the job faster and better,” he says, “we pay them to do it.”

Another of his favorite tactics: “rescuing stranded cargo.” Martial law prevents Ukrainians from sending money abroad—even money to ship wartime supplies into the country. But shipping is relatively inexpensive, generally a small part of any supply cost, and Mefford can make up the difference, in one recent case providing just $1,400 to transport $30,000 worth of donated medicine and other supplies from Dusseldorf, Germany, to Lviv.

More than three-quarters of the nonprofit’s funding goes to support homegrown Ukrainian relief efforts: grants to local governments, health-care providers, nongovernmental organizations, and groups like Swanson’s. Most grants are small: from $2,000 to $10,000. Grantees must make a formal request and document the need they are addressing. Years of experience working in Ukraine help Mefford vet potential grantees. In other cases, like Swanson’s, he starts with a small, one-time award designed to test what an applicant can do.

Swanson passed with flying colors, delivering a vanload of medicine from the border to Donetsk, and she’s now part of the nonprofit’s rapidly expanding operation: some 70 staff and volunteers, almost all of them Ukrainian—a network of networks helping to keep other Ukrainians alive.

Irek Czubak’s operation is also a network of networks, but more informal than Mefford’s, and its tentacles may reach even deeper into Ukrainian society, with grassroots volunteers like Mykola Piddubnyi and Irina Gavrilova doing much of the work in the field.

Piddubnyi doesn’t look like a typical caregiver. A tough former soldier with a shaved head and facial tattoo based on Mike Tyson’s trademark inking, Piddubnyi decided not to reenlist when Russia invaded in February. Based on his experience serving in eastern Ukraine in the last fight with Russia, from 2014 to 2019, he felt that he could do more good from outside the armed forces, supplying food, medicine, and matériel to troops and civilians on the front lines.

“A lot of volunteers are afraid to drive into the fighting,” he explains. “I’m a soldier. I’ve been there. I’ve been shelled. I’m not afraid.” If anything, the more dangerous the mission, the more he seems drawn to undertaking it.

He drives a small, shrapnel-scarred car, packed to the roof with cardboard boxes, and is usually accompanied by two aging cargo vans, also filled to capacity. He says that roughly 70 percent of what he takes into the war zone is for civilians, the rest for military units. His priorities start with children and the elderly, the closer to the front lines, the better.

He relies on contacts in the armed forces to help him identify the safest routes. Sometimes it’s an official “green corridor”—a road designated by the government for humanitarian transports and evacuations. In other instances, it’s just a back road, often unpaved, and it’s not unusual for his little convoy to drive 1,000 kilometers a day.

Piddubnyi and Gavrilova work as partners at the center of a network much like Swanson’s—spontaneous, informal, agile, and ever-changing, as volunteer members come and go. Piddubnyi relies on roughly a dozen volunteers. Gavrilova runs the warehouse in Lviv and draws on what she says is a web of about 90 people to cook, cadge, and purchase food and other supplies.

One group of older women in a nearby village works in shifts in a borrowed kitchen baking bread and cookies. Another village sends dumplings—according to Gavrilova, three busloads a day. Still other women conserve meat in repurposed jelly jars. One batch I saw featured handmade labels: “Come back alive and bring this jar back to Lviv.” Still other labels, affixed to boxes of baked goods, were drawn by local children: brightly colored images of everything from tanks to rainbows that Gavrilova says help to boost soldiers’ morale.

The network operates on a shoestring. Both Piddubnyi and Gavrilova have given up their day jobs. He borrows from friends to pay his rent. She has depleted the money she had been saving for her son’s education, using it instead to purchase supplies. His biggest need, he says, is cash to cover the cost of gasoline. Her main complaint on the day I visited was a dip in donations of nonperishable groceries.

This is where Irek Czubak comes in, one of Piddubnyi and Gavrilova’s biggest suppliers. An evangelical Christian Pole, Czubak has been operating charitable organizations in Poland and Ukraine for more than 25 years. One of his priorities before the war was connecting Jews and Christians, and when the Russians invaded, this work paid off in a vast web of contacts on both sides of the border—what Czubak describes as “Jews, Christians and atheists” he can call on for help delivering humanitarian assistance.

One old friend, a high-ranking official in the Ukrainian border control, helped Czubak and his brother evacuate 15,000 refugees in the first eight days of the war. Then, when most other relief groups were putting up welcoming tents on the Polish side of the frontier, the same official gave the brothers permission to work on the other side, in Ukraine, where the need was even more urgent—providing food and warm clothing to refugees waiting in line to be processed, often for as long as two to three days in the bitter cold.

Still another connection, to the Jewish Community Center in Krakow, has provided generous funding for Czubak’s operation. He looks to people like Piddubnyi and Gavrilova—locals in Lviv, Kyiv, Rivne, Kharkiv, and elsewhere with access to warehouses and drivers.

Also essential: sources that can provide intelligence—churches, synagogues, local officials, and military commanders who can identify exactly what kind of help is most desired. “It changes every day,” Czubak says. “And you’re no use unless what you’re sending is what’s needed that day.”

Czubak’s biggest recent coup: someone introduced him to a French businessman with ties to a group of villages in Northern France that wanted to contribute to the Ukrainian relief effort. So far, they’ve sent eight truckloads—big 18-wheelers, each carrying more than a ton of food—and eight more have been promised.

One arrived at Gavrilova’s Lviv warehouse the day I visited, a welcome boost for rapidly diminishing supplies. Two days later, Piddubyni and his convoy of battered vans were on the road, en route to Bucha, Irpin, and Hostomel, formerly occupied towns in the Kyiv region from which Russian troops had just withdrawn.

At the opposite end of the socioeconomic spectrum from Piddubnyi and Gavrilova, the founders of Ukraine Needs Wheels are young professionals in Kyiv—financial analysts, lawyers, and impact investors, many of whom have spent time in the U.S. Looking for a way to help in the first days after the invasion, several of them stumbled independently on the idea of buying vehicles, a practically ubiquitous necessity in war-torn Ukraine. Relief workers need vehicles to evacuate refugees. People bringing supplies into the country need vehicles on both sides of the border and in the interior. Medical personnel need ambulances and transports.

But arguably the sharpest need and the most vital to the war effort is among the armed forces—especially Territorial Defense units and volunteer battalions. Ukraine’s winning strategy in the first phase of the war relied on agile, guerrilla-style fighters who could infiltrate enemy positions and destroy tanks and artillery. These troops require Jeeps and pickup trucks. Other units lack vans to deliver supplies and transport wounded soldiers. Among the most critical necessities: four-wheel-drive vehicles that can go off-road, avoiding Russian mines and artillery by cutting through fields and forests. All these conveyances are in short supply in Ukraine.

The young men who would eventually come together in Ukraine Needs Wheels started small: individuals buying vehicles somewhere in Western Europe, often with their own money or funding from friends and relatives, then driving them across the border one at a time. The breakthrough came when the group realized that it had the expertise to operate at scale, fundraising in the U.S. and Europe to buy and transport vehicles in bulk.

The transport operation is relatively simple. One set of volunteers drives the cars from wherever they are purchased to the Ukrainian border. A second group loads them on a tow truck—by far the quickest way to get through clogged border checkpoints. A third crew takes care of the last leg—from the frontier to a designated military unit where a commander has requested a vehicle, whether for transport or other purposes. When I visited in early April, Ukraine Needs Wheels had delivered 45 vehicles.

Harder and more complex than coordinating transport was building an entity to sustain the operation—a semiformal team of volunteers that could function on a national scale. One group in Kyiv coined a name for the unit and worked, as co-founder Valerii Kondratenko put it, to “create a brand.” Other members of the network reached out to charitable organizations in the U.S. and Europe, building partnerships that would allow the group to channel funding into Ukraine.

One member who asked to remain anonymous explained the challenge: “It’s much harder to raise money for the army than for humanitarian assistance. Refugees and IDPs are a symptom. What’s causing the suffering is the war. But there aren’t many donors who want to hear that or want to write checks for the military.”

Ukraine Needs Wheels isn’t the only group I encountered funneling supplies to Ukrainian fighters. Come Back Alive is a long-established nonprofit launched in response to the last Russian invasion, in 2014. Close to the Ukrainian armed forces but entirely private—it receives no state funding—it raises money largely inside Ukraine and spends it exclusively on high-tech equipment, not basic gear like helmets or bulletproof vests.

Much of the technology is “dual use”—it has civilian and military applications—and Come Back Alive supplies no weaponry. “We want to protect life, not take it,” explained fundraising director Oleg Karpenko. But the equipment his group provides is essential for the war effort: items like night-vision goggles, thermal-imaging cameras, and quadcopter drones.

Karpenko says donations soared after the Russian invasion in February. In the war’s first month, the organization raised ten times what it took in from 2014 to 2021. But like virtually all the groups I encountered in Ukraine, Come Back Alive is seeing contributions drop as the war drags on and donor fatigue sets in.

Civil society is not enough. Even more urgent than fundraising, even as their operations expand, both Come Back Alive and Ukraine Needs Wheels echo Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky’s calls for heavier weaponry. Pickup trucks, drones, and other dual-use technology purchased by civil-society groups are better than no equipment. But they won’t be enough to win the war.

“The vehicles we bring in are effective for defensive operations,” explained Kondratenko of Ukraine Needs Wheels. “But if we want to regain territory or recapture our land, we will need something very different—equipment that gives us the same capability as our enemy.”

“We need long-distance artillery, long-range air-defense systems, tanks, and combat aircraft,” said Karpenko of Come Back Alive. “No nonprofit organization in the world can buy that kind of weaponry. That’s a job for government—government to government.”

“Still,” he concluded gravely, reiterating what I had heard from many people I spoke with in Lviv, “even if our international partners do not support us, we will keep on fighting with whatever we have. Our nation has proved what we can do—proved we can fight, proved we can support our fighters. And we will continue fighting until the end.”

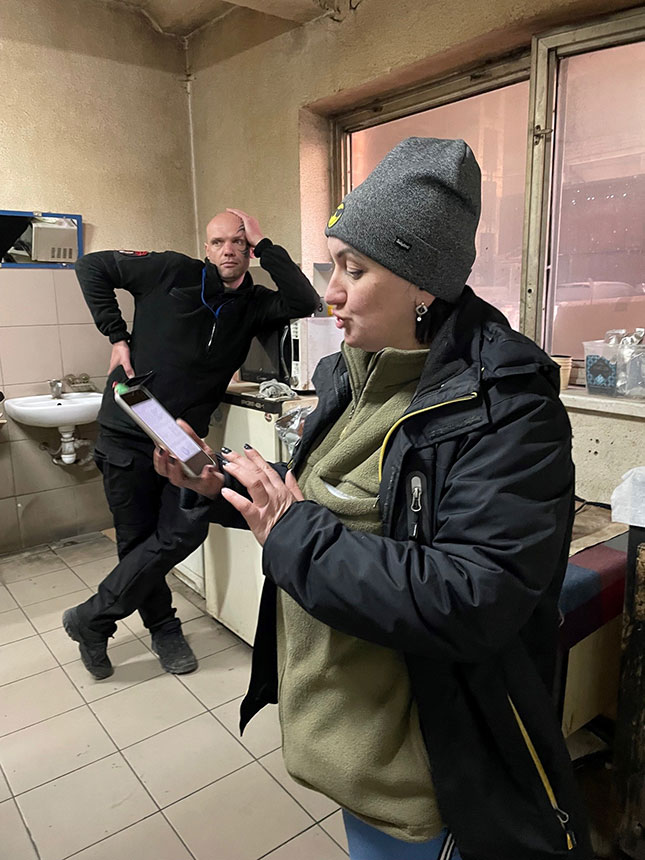

Top Photo: The canteen of a former movie theater, now a shelter for displaced persons—a location provisioned by Mykola Piddubnyi and Irina Gavrilova (Photo: Adam Reichardt)