Americans want to admit more high-skilled legal immigrants like doctors and engineers, according to a new poll by the Manhattan Institute. The poll found that Americans want a system that, above all, admits people who won’t be dependent on government welfare and who want to assimilate into the American economy and society.

Americans show their understanding of an important problem in the current system. Though the border crisis and illegal immigration get more attention, the United States faces an invisible immigration tragedy in all the physicians, engineers, entrepreneurs, and innovators who never make it to the U.S. because of our outdated process for legal immigration.

These missing doctors, engineers, and entrepreneurs hold back American innovation. Meantime, China has been making rapid progress in the number of patent filings relative to the United States. Canada and the U.K. are now the preferred destinations for international students seeking to study abroad. And a shortage of doctors exists in areas of the U.S. that are home to 98 million people. These are all symptoms of a breakdown that, if left unaddressed, will cause the U.S. to lose ground relative to China and other countries in the innovation race.

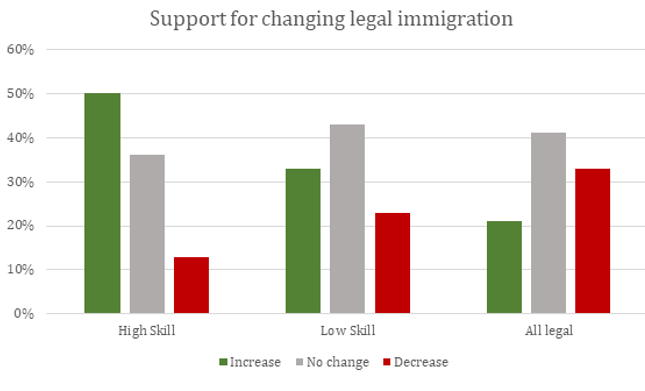

The Manhattan Institute poll, conducted by WPA Intelligence, found that more than 60 percent of Americans want legal immigration to be maintained or increased, while only 33 percent want it to be reduced. Half of Americans want more high-skilled immigrants, while only 13 percent want fewer. Even among those who want to reduce legal immigration, one-third want more high-skilled immigrants. Majorities of all ethnic groups, and especially Hispanics and Asians, support increasing high-skilled immigration. Regarding low-skilled immigration, 33 percent want more, 23 percent want less, and the rest want no change.

Interestingly, the poll found that Americans who want overall reductions in legal immigration outnumber those who want fewer high- and low-skilled legal immigrants. Though this result seems strange, and perhaps even contradictory, it may suggest that some Americans support skills-based immigration but also want to limit certain forms of legal immigration—like refugee admissions and family-based immigration—that don’t fit either category mentioned in the poll.

Americans’ support for high-skilled immigration may reflect a recognition of the fact that the U.S. currently places severe limits on it. Our current system is the product of the 1965 Immigration Act, which repealed the racial quotas prevalent since the 1920s and replaced them with a system that prioritizes family ties. The United States has changed a lot since 1965, and so has the world. We should revamp the system to prioritize immigrants based on their potential to assimilate and thrive economically, recognizing that we have a welfare state that traps generations of families in dependency.

The United States currently admits two categories of permanent newcomers: on the one hand, the immediate relatives of American citizens, who aren’t subject to quotas; and, on the other hand, non-immediate family members, workers sponsored by employers, refugees, and those belonging to other small categories—all of whom are subject to quotas.

Immediate relatives include the minor children, spouses, and parents of U.S. citizens who are at least 21 years old. Foreigners are generally eligible for permanent residence (green cards) by virtue of their immediate relationship to an American relative, unless they have violated certain laws. The U.S. admits nearly 500,000 immediate relatives every year.

All other categories are subject to quotas. Congress updated the 1965 quota in 1990 to admit up to 421,000 immigrants to adjust for population growth during that period. Of these 421,000 spots, 226,000 are reserved for non-immediate family members of U.S. citizens and permanent residents, such as siblings and adult children of U.S. citizens. Some 140,000 green cards are issued to immigrants because of their skills or because their work is in high demand in the U.S. (this includes investors). Finally, the U.S. awards some 55,000 green cards randomly in the annual “diversity” lottery to foreigners with at least a high school degree from countries that don’t typically send many immigrants to the United States. Other immigrants are admitted as refugees, so long as they meet the legal definition, in numbers chosen by the president.

The 140,000 green cards issued to high-skilled foreigners represent only about 14 percent of all green cards issued. And only about 70,000 of these go to the high-skilled immigrants themselves since their dependents also get green cards and they count against the overall quota.

What’s more, though the 1965 Immigration Act officially repealed racial quotas, in reality, it merely replaced discrimination by ethnicity with discrimination by country of birth. Per-country limits have resulted in decades-long wait times for Indian-born high-skilled immigrants living in the U.S. on temporary visas. And some of the children of these immigrants must self-deport once they turn 21, even though they have lived almost their whole lives in the U.S.

While skills- and employment-based immigrants all must meet stringent requirements—such as college degrees, extensive experience, and high salaries—family-based legal immigrants face no skills requirements or tests, not even for English-language ability. This is a senseless system, and Americans know it. Our Manhattan Institute poll found that about two-thirds of Americans agree with the proposition that these qualities—willingness to assimilate, ability to fill needed jobs, low likelihood of dependence on government welfare, English proficiency, and family ties—should improve an immigrant’s chances of being admitted. When asked to choose which factor is most important, 35 percent chose low likelihood of dependence on government welfare. In second and third place, respectively, are willingness to assimilate (24 percent) and ability to fill needed jobs (20 percent).

The literature on immigrant assimilation and economic outcomes backs up Americans in these views. Like all Americans, immigrants earn higher incomes if they speak English well and hold a college degree. While a lively academic debate persists about whether recent immigrants are assimilating at the same rate as past ones, we know that the most successful immigrants are those who come to the U.S. when they’re young, spend years here, have lined up job offers, have obtained higher education, and speak English.

A better approach to legal immigration would pool all green cards together and award points to applicants based on age (youth), education, employment, and English proficiency. This would result in immigrants who rely on less government assistance, pay more taxes, and perform jobs more likely to contribute to American innovation.

Other English-speaking developed countries learned long ago that prioritizing high-skilled immigration is good policy. Canada and Australia implemented points systems in 1967 and 1973, respectively, and now have the most highly educated immigrant populations of any developed nation. The United Kingdom followed suit after Brexit, and it’s on track to admit fewer less-educated Europeans and more highly educated Asians (debunking any potential criticism that such a system would be racist or discriminatory).

Shifting the U.S. system toward allowing more high-skilled immigrants wouldn’t require a major legislative overhaul by Congress. One simple but potent change would be to allow unused employment-based green cards from one year to carry over to the next in the same category, instead of going into the family-based system as they do now. At the same time, all unused family-based green cards in each category could be carried over to the employment-based categories directly rather than into other family-based categories. Making this fix could shift tens of thousands of green cards toward high-skilled immigrants every year. Legislators could also divert the diversity and sibling green-card categories into the employment-based system. Both measures could end the decades-long green-card backlog for high-skilled immigrants from India and increase high-skilled immigration substantially.

An overlooked impact of shifting some family-based green-card categories into the employment-based system is that these high-skilled immigrants would sponsor family members who are likely, on average, more highly educated due to assortative mating. Therefore, expanding employment-based immigration would also raise the average education of the fewer family-based migrants that are admitted.

Most Americans want a system that opens golden doors to immigrants eager and able to contribute to our society. Such a system harmonizes with Ronald Reagan’s vision of America as a “shining city upon a hill,” one “teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace.” That’s how Americans see their country, too.

Photo: Evgenia Parajanian/iStock