It is a sad irony that the teaching of science in American schools is so unscientific. In a more rational world, children would learn about nature and a mode of inquiry—the scientific method—that would awaken them to the awe, fascination, and surprise that the universe should inspire. Instead, the chronic problems afflicting K–12 education and the growing politicization of science have pushed us ever further from that ideal.

Science has been misused and poorly taught for centuries. Aristocrats in the United Kingdom espoused eugenics, Soviet Communists embraced Lysenkoism, and theists around the world credit the theory of Intelligent Design. The most enduring betrayal of science in the classroom today is biased teaching about the environment. Whereas eugenics was fueled by fear among the rich that the poor would overwhelm them, the fallacies of green education emanate from fear on the left that fossil-fuel companies and capitalism are ruining the planet. This fear has suffused curricula since the 1970s with an ever-growing list of alarms: pesticides, smog, water pollution, forest fires, species extinction, overpopulation, famine, rain forest destruction, natural resource scarcity, ozone depletion, acid rain, and the great absorbing panic of our time: global warming.

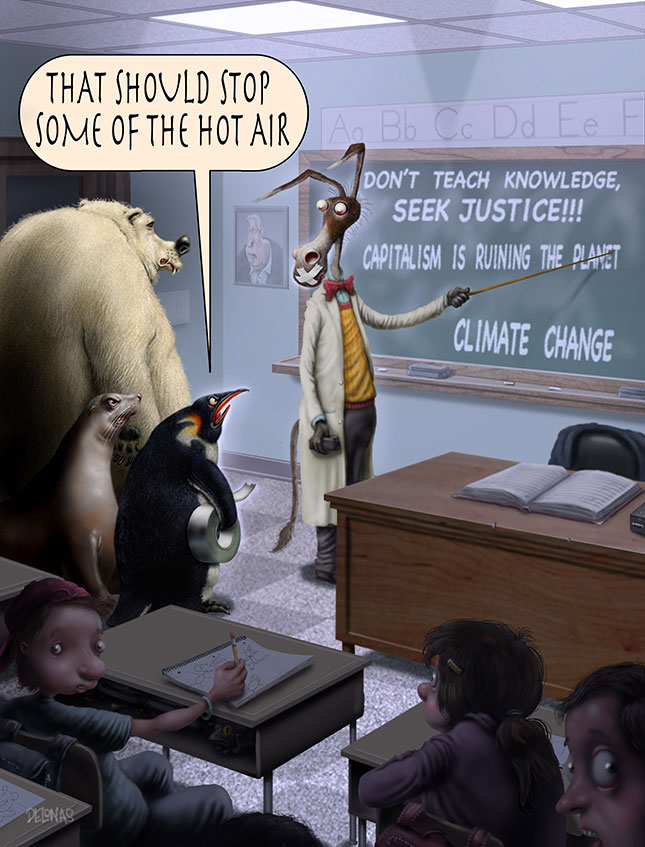

The choice and treatment of these topics reflect a worldview that teachers absorb early in their training. The mission of education, they’re told, is not to teach knowledge but to seek justice and make the world a better place. Their task is to show students that we are destroying the environment and to empower them to help save it, primarily through government action.

These premises inform everything about environmental education: the standards of learning that states impose on school districts; the position statements from the associations of science teachers; the course work and texts in education schools; the training that educators receive throughout their careers; and the textbooks, lesson plans, field trips, and homework assigned in all grades.

One review of textbooks used in secondary schools concludes:

For the moment at least, ecological doomsayers rule the cultural roost. Fire-and-brimstone logic is combined with fear-and-doomsday psychology in textbooks around the country. [The story] could be retold tens of thousands of times, about children in public and private schools, in high schools and at elementary levels, with conservative and with liberal teachers, in wealthy neighborhoods and in poor. A tidal wave of pessimism has swept across the country, leaving in its wake grief, despair, immobility, and paralysis. . . . Why should our students be misled?

The moment was 1983. The passage is from Why Are They Lying to Our Children?, a book by the late Herbert London, then president of the Hudson Institute. “The materials in environmental education have nothing to do with environmental science. . . . [T]hey are wholly political,” London wrote three years later in a teacher guidebook, Visions of the Future. “The effects are pernicious. It is no longer possible to have a sensible discussion. You cannot talk about historical perspective or risk/benefit tradeoffs. You have to follow the utopian path.”

In 1993, Garbage magazine ran a lengthy review of teaching materials and practices. The headline asked: “Environmental Education: Is It Science, Civics—or Propaganda?” The author, Patricia Poore, wrote:

I was struck by the repetitive topics, the emphasis on social problems rather than science background, and the call to activism.…

Perhaps most significant in these books is what’s not included: Every chapter devoted to elephant extinction or garbage crowds out a rich array of important environmental basics. Perpetuation of outdated assumptions is rampant in what is included. The piecemeal curriculum contains oversimplification and myth, has little historical perspective, is politically oriented, and is strongly weighted toward a traditional environmentalist viewpoint, i.e., emphasizing limits to growth, distrust of technology, misinformation concerning waste management, and gloomy (if not doomsday) scenarios. . . .

What is even more striking than the imperfect content of the curriculum, however, is its apocalyptic tone.

Perhaps the most influential critics of environmental education were Michael Sanera and Jane Shaw, whose book Facts Not Fear: A Parent’s Guide to Teaching Children about the Environment (1996) sold 100,000 copies. (Chapter titles include “Trendy Schools,” “At Odds with Science,” and “The Recycling Myth.”) Sanera also published detailed content analyses of environmental science resources for K–12 students and of the textbooks and syllabi used in colleges of education. The authors found the same biases, mistakes, and omissions that Poore and London had found. A major study by the Independent Commission on Environmental Education, Are We Building Environmental Literacy?, reached similar conclusions.

Politicizing Science Education, a report in 2000 by the biologist Paul Gross, found that environmental education lacked rigor: “Too often the science goes begging. Environmental education becomes attitude adjustment. Students learn about such things as primitive paragons of eco-wisdom—indigenous peoples, for example—‘living in harmony with nature’; or about the ecological Satans, development and industrialization; or of Earth poisoned in its air, water, and soil. But they do not learn much of the science needed for scientific understanding.”

Though characteristically American in its fretfulness and zeal, the unwavering focus by teachers on crises and advocacy is not entirely homegrown. It was animated by a series of conferences and declarations orchestrated by the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization in the 1970s. UNESCO’s Belgrade Charter in 1975 called for “a worldwide environmental education program” to help mount “an all-out attack on the world’s environmental crisis.” All efforts will be short-lived, the charter declared, unless “the youth of the world receives a new kind of education”—one that begins in pre-K, is interdisciplinary, and emphasizes “active participation in preventing and solving environmental problems.” For the U.S. teacher eager to remedy injustice and alleviate suffering, UNESCO’s rhetoric ratified the progressive ideals that education schools have taught for decades.

The great environmental crisis for educators today, of course, is global warming. Reinforced by a media schooled in their views, teachers have grown ever more extreme in their advocacy. Twenty years ago, Sanera complained that the Environmental Protection Agency was training educators to teach children to write their congressmen and hold press conferences to “support [EPA’s] radical environmental policies.” Today, school leaders encourage students to cut class, stage sit-ins outside congressional offices, and join strikes to demand even more radical policies, such as the Green New Deal.

It’s hard to know how many of America’s 3.6 million teachers teach climate change, or how they teach it. A National Center for Science Education survey of 1,500 public school science teachers found that 90 percent of middle schools and 98 percent of high schools teach about global warming and that 85 percent of the teachers who teach it agree with the statement: “I emphasize the scientific consensus that recent global warming is primarily being caused by human release of greenhouse gases from fossil fuels.” The survey, the largest of its kind, is called Mixed Messages, because 31 percent agreed with both the above statement and this one: “I emphasize that many scientists believe that recent increases in temperature is [sic] likely due to natural causes.” Which message teachers actually emphasize can be inferred by the finding that almost all teachers agreed that they are “linking science to action” by discussing “positive steps that industry, government, or the students themselves can take to alleviate recent global warming.” Nine out of ten middle school teachers—and 95 percent of earth science teachers—said that they told students that they should do things like walk to school or turn off lights at home.

State standards and tests shape much of the instruction in public schools. The National Center for Science Education found that standards in at least 36 states mention the “reality of human-caused climate change.” Nineteen states, including California, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey, have adopted the Next Generation Science Standards, a 600-page tome created by a consortium of states, the National Science Teachers Association, National Research Council, American Association for the Advancement of Science, and Achieve, a nonprofit education group. The phrase “climate change” appears in the document as a “core idea” for middle and high school. The phenomenon is presented as fact, as are its supposed consequences—loss of biodiversity, species extinction, changing rainfall patterns, disruption of the global food supply, glacial ice loss, and mass migration due to rising sea levels. Nowhere do the standards say that both the nature of the phenomenon and its consequences are matters of pitched debate, or that rival theories to explain climate change exist—put forth not by flat-earthers or disbelieving parsons but by serious scientists. (See “Climate Science’s Myth-Buster,” Winter 2019; and “An Unsettling Climate,” Summer 2014.)

At least 15 federal or federally funded websites offer free teaching materials about climate change and its dangers. The entities include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Science Foundation, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Energy, and U.S. Global Change Research Program. The sites offer thousands of resources, including lesson plans, games, and videos for all grades. No website funded by government or universities or K–12 education groups is devoted to teaching about the scientific debate.

Two environmental-education courses with national reach—the College Board’s Advanced Placement Environmental Science and the International Baccalaureate’s Environmental Systems and Society—exhibit the usual biases and add some new ones. IB dethrones the scientific method as a prime source of knowledge and replaces it with “eight ways of knowing.” Along with sense perception and reason, these include faith, emotion, imagination, intuition, language, and memory. Students are expected to use inductive and deductive reasoning and to appreciate the importance of evidence, but they must also “use other methods traditionally associated with the human sciences” such as “history, the arts, ethics, religious knowledge systems and indigenous knowledge systems.”

The threat of anthropogenic global warming is taught as fact—though what is meant by “fact” is unclear—and the debate among scientists is attributed not to disagreements over evidence or interpretation but to “conflicting environmental value systems,” or EVS. “There is a spectrum of EVS, from eco-centric through anthropocentric to technocentric,” the course guide says. “EVS are individual; there is no ‘wrong’ EVS.” Students “should be encouraged to develop their own.”

The guide includes a bibliography of 74 works, none skeptical of global warming. The phrase “climate change” appears 52 times and “international-mindedness” 41 times. “Natural variation” appears once (in a unit on evolution). The terms “solar cycle,” “cosmic rays,” “volcanic activity,” “El Niño–Southern Oscillation,” “Atlantic Meridional Circulation”—all phenomena that affect climate but are unrelated to fossil fuels—appear not at all.

The stated goal of the AP course is not to teach science but to help students “achieve understanding in order to propose and justify solutions to environmental problems.” Two of the nine units focus on pollution; another covers the harmful effects of mining, overfishing, agriculture, and urbanization. The final unit—the most heavily weighted on the AP final exam—is devoted to climate change and ozone depletion.

The AP course treats anthropogenic climate change as a major problem—so major that the College Board has maintained a separate section of teacher-training material on the topic since 2006. The material includes a list of problems caused by global warming, designates these problems as “essential knowledge,” and then definitively states the solution: “reduce consumption.” Teachers are advised to encourage students to conduct a “personal energy audit” of their homes.

The course covers alternative theories to explain climate change but only for the purpose of refuting them, and it does so with assertions that are inapposite or in dispute. For instance, students learn that “fluctuations in solar output” are too small to have a significant effect on global temperatures. In fact, physicists Nir Shaviv, Henrik Svensmark, and others have demonstrated that variations in solar activity affect the number of cosmic rays that reach the earth, which affects the rate of cloud formation, which, in turn, significantly affects global temperatures.

But to anatomize the decades of distortion in environmental education is a sideshow to an older, bigger problem: the refusal or inability of teachers to adopt scientifically proven methods to teach anything. Compared with medicine or engineering, teaching remains a backward field, dominated by myths and misconceptions. The largest experiment ever to compare teaching approaches, sponsored by the federal government in the 1970s and known as Project Follow Through, found that 21 of the 22 models in the experiment failed to improve student achievement. These models and the thinking behind them continue to define education practices today. (See “Pre-K Can Work,” Autumn 2008.) They endure because the public they harm does not know enough to challenge them and because educators—unlike, say, surgeons and cell-phone makers—don’t face enough pressure to replace old ways with new ones that work better. Hence, the nation’s mediocre test scores in reading, science, and math.

The only model that succeeded, Direct Instruction, created by the pioneering inventor Siegfried Engelmann, has more evidence validating its effectiveness than any other mode of instruction. But educators have shunned Direct Instruction for decades, for much the same reason they have shunned more rigorous approaches to teach about the environment: both violate their biases. (See “An IDEA Whose Time Has Come,” Winter 2019.) Indeed, the director of the National Center for Science Education says that its approach to teaching science is “diametrically opposed” to Direct Instruction—which is to say, diametrically opposed to what science says works best to teach science.

Direct Instruction works because, unlike the other models, it is a product of the scientific method. Hundreds of field-tested details go into Engelmann’s programs, and all must be scrupulously followed to accelerate student learning. In contrast, state standards, as well as the textbooks, curricula, and training they inspire, are untested products, forged from unproven theories in a political process antithetical to science. That is why they have consistently failed to improve student learning, notwithstanding repeated efforts over many decades to strengthen them.

The Next Generation Science Standards are so convoluted that it is hard to imagine how they would help anybody teach any science at all, much less a fast-changing, contested science like climatology. Many concepts are too generic. Here’s one for third through fifth grade: “People’s needs and wants change over time, as do their demands for new and improved technologies.” Many performance expectations are unclear. Here’s one for kindergartners: “Analyze data to determine if a design solution works as intended to change the speed or direction of an object with a push or a pull.” What kind of data will a five-year-old analyze? Other standards pack too much science into one statement, often without sufficient instruction from earlier grades. This one for high school would challenge a graduate student: “Analyze geoscience data and the results from global climate models to make an evidence-based forecast of the current rate of global or regional climate change and associated future impacts to Earth systems.”

In Massachusetts, the Next Gen standards are less clear and rigorous than the standards they replaced. Here’s a first-grade standard for the state from 2006:

Identify objects and materials as solid, liquid, or gas. Recognize that solids have a definite shape and that liquids and gases take the shape of their container. Using transparent containers of very different shapes (e.g., cylinder, cone, cube), pour water from one container into another. Observe and discuss the “changing shape” of the water.

Here’s the Next Gen standard that replaces it:

Investigate and communicate the idea that different kinds of materials can be solid or liquid depending on temperature.

The word “gas” in the new standards does not appear until fifth grade. Bemoaning the delay, Paul Gross asks: “Don’t Massachusetts’ children watch water boil or receive balloons on their birthdays?”

Also disfiguring the standards is the nonsensical idea of constructivism, which holds that the mind builds its own knowledge from personal experience and that there is no objective truth, but rather a range of personal “truths” and “types of knowledge” to be created or discovered. The idea, which underpins IB’s treatment of science, has enthralled education schools since the 1980s. In Politicizing Science Education, Gross explains its allure:

Exploring this bizarre amalgam of postmodernism, epistemological relativism, and old learning theory, the astounded layman may well ask, “How can anyone teach natural science under a theory of science so hostile to its purposes, so blind to its practices and achievements?” The answer: political appeal. . . . Since no “knowledge” can be better than any other, and science is just one way of knowing the world, a way, moreover, that is characteristic of white European males, it is perfectly all right if other kinds of people don’t do it well. This, happily, reduces the teacher’s burden of knowing science (or mathematics). Nothing of the results of your teaching will matter much except the extent to which you adjust children’s attitudes. In short, politics.

In a 1959 lecture, English novelist and physical chemist C. P. Snow observed: “So the great edifice of modern physics goes up, and the majority of the cleverest people in the western world have about as much insight into it as their Neolithic ancestors would have had.” Scientific illiteracy is nothing new. Nor is the ruination of science by human frailty. Physician and epidemiologist John Ioannidis, codirector of the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford University, has shown that most published research findings are false. The National Research Council, founded in 1916 to “encourage applications of science as will promote the national security and welfare,” convened the committee (said to include Nobel laureates) that produced the manifestly unscientific Next Gen standards.

One brief act in the global warming drama shows how far the ruination has spread. Graduate students in climate-related sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology organized and marched in the Global Climate Strike in 2019, carrying signs such as “You Lie=I Die,” “Break free from fossil fuels,” and “Climate Action Now.” Can we trust that these future scientists understand what science is, and what it calls for? Can we trust that their research will be sound? Will they heed Richard Feynman’s warning about the dangers of self-deception? “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.” Will they search for truth, though the heavens fall?

When the scientists whom teachers depend on are not scientists but advocates, we can expect teachers to become advocates as well. It is the easier route for both. Science is hard: few can do it; few understand it or teach it well. Diverse forces have struggled to prevent its abuse—Herbert London was a conservative, Gross a liberal, Sanera and Shaw libertarians, Poore an independent—but the same idols and villains reign. Science advances. Science instruction does not.

Top Photo: Chinnapong/iStock