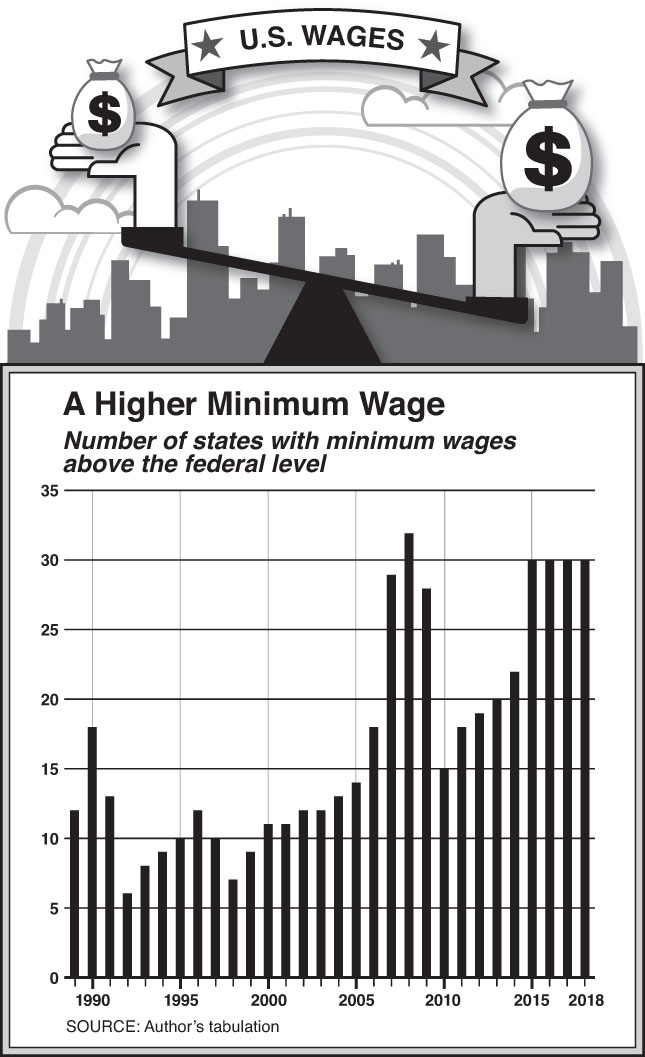

Battles over minimum-wage increases are raging across the country. Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia have raised their minimums since 2014, and 44 municipalities now have higher local minimums, up from just five in 2012. Congress is considering the Raise the Wage Act, which would phase in a nationwide increase to $15 an hour over the next few years. Most of the debates focus on the number of jobs that might be lost from mandated increases and balancing these possible effects against the higher incomes.

This emphasis is misguided. When politicians point to crude job counts to justify policies like protectionist tariffs, economists routinely mock these lines of argument. Yet they seem content to accept them when it comes to the minimum wage. Data limitations are partly to blame—counting the number of people employed is relatively straightforward, while other aspects of a job, even the number of hours worked, rarely get tallied with any consistency. But the notion that the value of a job rests simply on whether one is employed and the level of cash compensation makes for unimaginative economics.

Measuring other margins of adjustment to a higher minimum is indeed more difficult than counting jobs. Still, it’s obvious that there’s much more to the labor market than wage levels or the existence of jobs; there are, for example, work hours, job satisfaction, and flexibility, and employers will likely start adjusting these other aspects before they cut workers. This is convenient for minimum-wage advocates, who are happy to point to negligible job losses a few months or a year after an increase as evidence that the minimum wage doesn’t affect the labor market. But these other adjustments have real consequences.

It’s not hard to see why firing employees is one of the last levers an employer will pull in response to rising labor costs. Firing workers is unpleasant for managers and bad for the morale of remaining staff, as R. J. Burke and D. L. Nelson demonstrated in a 1997 paper. It can require costly changes to the way a firm does business—for example, a restaurant can’t switch instantly from table service to counter service, or even introduce a burger-flipping robot overnight. Higher labor costs force employers to find other margins to adjust.

Cutting hours is one approach, including opportunities for lucrative overtime work. After Seattle raised its minimum wage from just under $10 per hour in 2014 to $13 per hour in 2016, reductions in hours worked were much more striking than the reduction in the job count, as shown in research by the Seattle Minimum Wage Project. The nature of the job can change, too, with employers expecting more effort from their employees in exchange for those higher wages. This is nothing new: a 1915 Bureau of Labor Statistics report on the effects of one of the first minimum wages in the United States noted that workers “contended that formerly they had gotten through the day without any hurry or strain. . . . Now, they said, they are under constant pressure from their supervisors to work harder; they are told the sales of their departments must increase to make up for the extra amount the firm must pay in wages.”

Advocates often claim that the higher minimum wage shifts more bargaining power toward workers. But the opposite is true. Well-educated workers are familiar with the idea of trading off lower wages for better working conditions—what economists call a “compensating differential.” A minimum wage prevents lower-skilled workers from doing the same. A single mother, say, might be willing to accept a slightly lower hourly wage if it allows her to leave work early on occasion to take her child to the doctor. While hard data are scarce on these kinds of difficult-to-observe facets of a job, surveys show that employers hold to stricter standards on scheduling in the face of higher labor costs. Other research shows that workers will give up as much as 20 percent of their wages to avoid having their employer set their schedule on short notice. And the employer’s attitude can change. A manager is likely to be less forgiving of transgressions if pay is artificially high, especially when dozens of workers would leap at the chance for that job. Cuts in nonwage benefits can claw back some of the gains on the wage side, too. The generosity or even provision of employer-provided health benefits can fall. Other benefits, such as free parking, meals, and uniforms, can get cut as well.

In fact, an employee may have been happy with the previous combination of wages, benefits, expected effort, and working conditions. Research shows that these types of nonwage amenities “play a central role in job choice and compensation.” We should take workers’ preferences seriously, rather than acting as if they have no agency in their life decisions. Minimum-wage increases can force them to accept a total compensation package that’s less desirable and ultimately leaves them worse off.

Of course, businesses have other ways to change their operating model to reduce employment costs. There has been a marked move toward shifting work onto customers, for example, particularly in the restaurant industry—what has been termed “customer-labor substitution.” Even in the fine-dining segment of the industry, counter-serve and self-busing are becoming increasingly common. Standing in line to order at the counter may not seem like a big burden, though it probably makes first dates even more awkward; its true impact is on lost job opportunities in the service sector. And if this new dining experience is less pleasant for consumers, then they will eat out less, further reducing the need for labor.

Businesses can also substitute capital for labor. Kiosk- or tablet-based ordering in restaurants may be the most obvious example, but routine tasks performed by low-skill workers are susceptible to automation across industries when the cost of labor goes up. Even in manufacturing, higher minimum wages lead to increases in capital investment, reductions in hours for low-wage workers, and a greater likelihood that an establishment will go out of business, a recent study by Yuci Chen found.

Focusing on job counts hides another unpleasant implication of the minimum wage: the substitution of one type of worker for another. After all, just because a job gets filled does not mean that the same person—or type of person—is filling it. Looking back at the original debates about the minimum wage at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, this kind of social engineering was a feature and not a bug. The progressives of the time, including many prominent economists, believed that the government should take a firm hand in the improvement of society, and that meant its genetic stock as well. Thomas Leonard’s excellent book Illiberal Reformers covers this history in detail. These reformers viewed the minimum wage as a useful way to separate out the “unemployable,” who were not productive enough to secure jobs at or above that level, with explicitly racist and eugenicist reasoning. Sidney Webb, cofounder of the London School of Economics, explained in 1912 that “a legal minimum wage . . . [ensures] that the surplus of unemployed workmen shall be exclusively the least efficient workmen.” Around the same time, Frank Taussig, editor of the prestigious Quarterly Journal of Economics for decades, wrote in his Principles of Economics textbook that the unemployable “should simply be stamped out. . . . We have not reached the stage where we can proceed to chloroform them once and for all; but at least they can be segregated, shut up in refuges and asylums, and prevented from propagating their kind.” Webb, Taussig, and their contemporaries understood that employers would shift toward more productive workers if they had to pay higher wages.

Productivity, of course, correlates with age, experience, and education. Extensive evidence suggests that employers do respond to higher minimum wages by changing the types of workers they hire. Teenagers with more experience or from more affluent families are more likely to have jobs than their less affluent counterparts. Even if the raw number of jobs doesn’t change much, workers with more experience tend to be the ones keeping or acquiring jobs, at the expense of the less experienced. Younger workers and those without high school diplomas are less likely to be employed, a trend driven by an increase in employer demands for high school diplomas, even for jobs that don’t really require them. By shifting to more productive workers, research has shown, employers have offset about half the increased labor costs from recent minimum-wage increases.

The workers who’ll be most affected by these shifts, in other words, are those already at the margins of the workforce. At artificially high wages, employers lose the flexibility to take a chance on a prospective worker with, say, a felony conviction—they simply can’t afford to take the risk. And without that first step onto the job ladder, it’s tough for such prospective workers to gain the experience that allows for upward mobility. Minimum-wage jobs are rarely pleasant, but among those who remain in the labor force, wage increases tend to be fairly rapid, with about two-thirds of workers earning above the minimum wage within a year.

Even in an era of unprecedented low unemployment, fewer than two in five adults lacking a high school diploma have a full-time job. Among young minorities without a high school diploma, the rates are even lower. And it’s the young who are most affected by the minimum wage: about half of minimum-wage workers are under 25.

That statistic hides a lot of heterogeneity, however. Among those young workers, half are high school or college students. Ten percent of households with a minimum-wage worker in them earn over $150,000 per year, and just 14 percent receive food stamps. It’s no surprise, then, that higher-income households benefit significantly more than low-income households from minimum-wage increases, as estimates by the Congressional Budget Office reveal.

The full effects of the higher minimum wage’s impact on the workforce may take years to show, as less qualified individuals have difficulty finding gainful employment, get discouraged, and leave the labor force. This, again, is not a new idea: H. B. Lees Smith wrote in 1907 that “the enactment of a minimum wage involves the possibility of creating a class prevented by the State from obtaining employment.” It bears repeating that no one claims that low-wage jobs are fun, but as the late left-wing economist Joan Robinson put it, “The misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.” Statistics show that unemployment and underemployment are far greater contributors to poverty than low wages.

Thus, the real question is whether the minimum wage is good antipoverty policy. Does it transfer resources from high-income households to low-income households? Does it preserve incentives to work and to hire?

The minimum wage is a blunt instrument. It does not distinguish between the teenage child of a wealthy family and a single-mother high school dropout; indeed, it encourages employers to prefer the former even more than they likely already do. So it fails on the first count. And while workers certainly prefer to be paid more rather than less, the minimum wage violates the “all else equal” assumption on which economists rely, as employers find other ways to reduce labor costs. Ultimately, an increase in that cost of labor will reduce employment. For myriad reasons, it takes time for the minimum wage’s effects to be seen in the number of jobs, even as it affects the nature of the jobs themselves and the types of people who fill them.

The current proposals for minimum wages at $15 (or more) an hour are far outside the scope of American experience. Over the last 30 years, the minimum wage has directly affected no more than 5 percent of the workforce. But median wages for hourly workers are below $15 an hour in 19 states, and the same is true for big parts of high-income states like New York and California. That is, in many parts of the country, more than half of hourly workers would be subject to the new minimum wage. To some, this means that the overall effects are uncertain. But the uncertainty runs only in one direction: How bad will the effects on workers be?

The effects of the minimum wage on employment are likely to be nonlinear. Employers will adjust through other means, often making workers worse off in ways that aren’t generally visible to researchers. At a certain point, though, firms have no more ways to adjust, and then they will either lay off workers or find themselves unable to stay in business.

Enhancing economic mobility and alleviating poverty are of paramount importance. But the minimum wage is the wrong tool for the job. It lends itself easily to slogans and gestural politics, but it’s not a real solution for real problems.

Photo by David McNew/Getty Images