Congress’s impeachment proceedings against President Donald Trump are polarizing the country along largely partisan lines, but they also offer an opportunity for constitutional reflection. According to Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution, “the Senate shall have the sole power to try all impeachments.” Barring any unforeseen circumstances preventing the House from exercising its “sole power of impeachment” as defined in Article I, Section 2, it appears that the Senate will assume that role once again. Perhaps history—in this case, the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson—offers the most instructive lessons for understanding the process.

Historians haven’t been kind to Johnson, and for good reason. His blatant racism and obstruction of reasonable Reconstruction policies place him in a tier of presidents who failed dramatically to meet the challenges of their time. But these same historians often defend Johnson when reviewing how his congressional opposition sought to remove him from the White House. Over time, Johnson’s impeachment came to be viewed, correctly, as a partisan endeavor resulting from the majority party’s power in both chambers. Legislators who stood against this partisanship protected constitutional principles over their party’s demands.

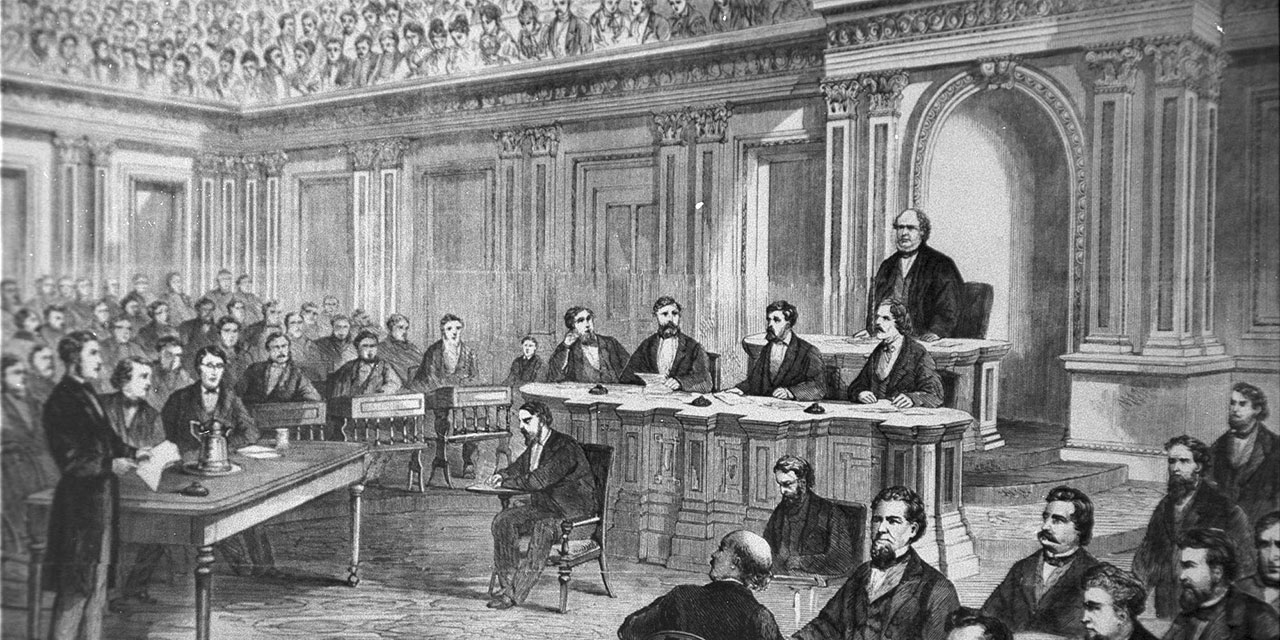

Those who led the 1868 impeachment and trial of Johnson—the first of a president in American history—are mostly forgotten today. Few can recall those who shepherded the articles through the House and presented the case against Johnson in the upper chamber; and few can name the president’s defenders or the Senate’s president pro tempore, who stood to gain the role of “acting president” if impeachment occurred. Even Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War whose dismissal led to eight of the 11 impeachment articles against Johnson, has been relegated to a footnote in this unprecedented saga. The figure who still looms largest over the event’s legacy is Edmund Ross, a Republican senator from Kansas who voted against the conviction of Johnson, a Democrat. Ross later recounted his thoughts as he voiced his vote in the upper chamber: “I almost literally looked down into my open grave.” He was right about his political future. Johnson escaped conviction in the Senate by a single vote, and none of the ten Republican Senators who voted “not guilty” won reelection.

In 1788, Alexander Hamilton anticipated Ross’s concern about constitutional clauses twisted for partisan advantage. With impeachment, he wrote in Federalist 65, “there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.” Ross wrote years later about the importance of his vote: “In a larger sense, the independence of the executive office . . . was on trial. If . . . the president must step down . . . upon insufficient proofs and from partisan considerations, the office of President would be degraded . . . and ever after subordinate to the legislative will.”

The significance of Ross’s nonpartisan vote should ring loudly today. Instead, its example is lost in a hyper-partisan atmosphere where short-term political agendas are prized over more principled considerations. It’s often said that history repeats itself. In the coming weeks, we’ll see if the Trump impeachment drama carries any echoes of the Johnson ordeal.

Photo: Impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson (Library of Congress/Getty Images)