A scrawny tree grows on Broome Street in downtown Manhattan, its presence modest and easy to miss. No plaque informs passersby that the tree was planted in honor of Jane Jacobs, the writer and activist whose advocacy and ideas about how cities thrive saved not only this street but all of SoHo, Washington Square, and much of Greenwich Village from destruction. The tree commemorates Jacobs’s now-legendary (and victorious) nine-year battle with her nemesis, city planner Robert Moses, the champion of vast urban-renewal efforts that tore up entire neighborhoods in favor of bridges, expressways, and gigantic public-housing projects. Moses’s initiatives, which included trying to make New York more automobile-friendly, made him, for Jacobs, “the master obliterator”—a slayer of cities.

When Jacobs’s classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, first appeared in 1961, New Yorkers were fleeing the city for the safety and security of the suburbs. New York was struggling to fill commercial space and attract investment, and tourists were staying away because of high crime and failing city services. Jacobs didn’t believe that New York was fated to decline. Death and Life was an opening salvo of her war on the then-fashionable notion of urban renewal, which, she argued, would make the city’s problems much worse by bulldozing living neighborhoods. From her modest house on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village, Jacobs championed the “intricate sidewalk ballet” of life. City streets and neighborhoods, she believed, should have—and, at their best, do have—more than one primary function, with new and old buildings mixing residential and commercial uses. Blocks should be short and populations dense, to ensure pedestrian traffic and what Jacobs called “eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street. The buildings on a street equipped to handle strangers and to insure the safety of both residents and strangers, must be oriented to the street. They cannot turn their backs or blank sides on it and leave it blind.”

Above all, Jacobs spoke for an organic approach to city development that would often find itself at odds with the broad-scale visions of urban planners. “There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city,” Jacobs wrote in a 1958 Fortune article. “People make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

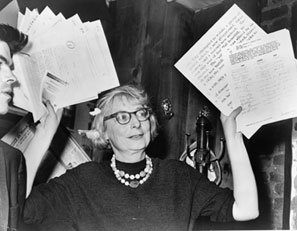

Such ideas represented a revolution in thinking about urban planning. Lacking even a proper college degree, initially dismissed as an amateur by planning giants such as Sir Patrick Geddes and Ebenezer Howard, architect Le Corbusier, and urbanist Lewis Mumford, Jacobs, with her bottom-up, pragmatic views, eventually prevailed. The destruction of vibrant neighborhoods, designated by planners and developers as “slums” in the name of what Moses called the “great scythe of progress,” fell into disfavor.

Since then, new threats to human-scaled urban neighborhoods have emerged, driven less by central urban-planning schemes—though some of those endure—than by New York City’s renewal over the past two decades, which has sent real-estate prices soaring and unleashed fierce competition for space in the very places Jacobs fought to protect. (The paradox inherent in the triumph of Jane Jacobs’s philosophy is that, had she not emigrated to Canada so that her sons could avoid serving in the Vietnam War, she might no longer have been able to afford her home in Greenwich Village or in some of the other neighborhoods she helped save.) Shifting neighborhood dynamics—and the high cost of living in the city generally—threaten to price out middle-class residents as well as the small businesses that make cities diverse and provide their leading engine of organic economic growth. Today’s intense demand for a foothold in places like Broome Street ironically reflects the influence of the very ideas that Jacobs promoted. Indeed, Jacobs’s ideas have become mainstream—so much so, notes architectural critic Paul Goldberger, that they’ve become “corrupted,” with developers citing her to justify massive building projects that she would almost certainly have opposed.

Beijing may be the city of the future (if its air is breathable), and Paris, the city of light, despite its absence of winter sun. London may have attracted, at last count, 76 Russian billionaires as residents. But New York—open, diverse, secure, economically and culturally thriving—is now the place to be for the superrich. Even those who don’t intend to live here consider New York a safe place to park their capital, especially in the form of real estate. In response to soaring demand, New York and its skyline are undergoing the most dramatic transformation since the construction of the first skyscrapers.

What would Jacobs have made of some of the most ambitious projects? It’s safe to say that she would have despised Atlantic Yards, recently rechristened Pacific Park, a much delayed, government-subsidized $4.9 billion urban-renewal plan to build the largest real-estate project in Brooklyn’s history, including 16 high-rises and 6,000 mixed-use residential and commercial units on a 22-acre site of rail yards owned by New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority. Developed in 2003 by Bruce Ratner and his company, Forest City Ratner, Atlantic Yards also relied on New York State to seize the property, through eminent domain, of small but often thriving businesses and of apartment owners on some of the 40 percent of the site not located on the rail yards; in their place would go a massive new development, the centerpiece of which would be a state-owned, privately operated for-profit sports arena, the Barclays Center, which opened in 2012 as the home of the Brooklyn Nets professional basketball team. (In 2015, the New York Islanders moved in to play hockey at Barclays.) Last year, the project was renamed Pacific Park when the Shanghai-based, Chinese-government-owned Greenland Group bought a 70 percent stake in the venture but not in the New York State–owned, privately run arena.

Barclays’ initial stadium design, by “starchitect” Frank Gehry, was quietly scrapped early on in favor of a smaller, cheaper, no-frills arena. Spokesmen for the center have called it a financial and development success that has stimulated commerce and created jobs in the area. Barclays employs 2,000, with 1,600 of those workers living in Brooklyn. Tucker Reed, president of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, whose members include Forest City Ratner, told the Daily News last year that retail vacancies near the stadium had fallen by 27 percent and that sports and big-ticket events, such as the MTA Video Music Awards, were helping to fill Brooklyn hotel rooms.

Yet while Jacobs might have liked the bustle around Barclays and the opening of new retail businesses, she would have been appalled by, among other things, the government’s use of eminent domain and other subsidies for private projects like Pacific Park—a half-billion dollars’ worth, in Ratner’s case. And she generally wasn’t a fan of arenas (though she did support the building of one in her adopted city of Toronto, where she moved in 1968). As a rule, she argued, such venues attract people intermittently, not consistently through the day or night. Architecture critic Nicolai Ouroussoff described Barclays as destined to be “a black hole in the heart of a vital neighborhood,” and critics note that the vast majority of Barclays jobs, as is usually the case with stadia, are part-time and not well paid.

MaryAnne Gilmartin, Forest City Ratner’s chief executive officer, tried to wrap the Atlantic Yards / Pacific Park Report development in Jacobs’s philosophical mantle. It might surprise some critics to know, given her “developer DNA,” she said a while back, that she “identified more with Jane Jacobs than Robert Moses.” But true Jacobeans are skeptical. “I think Jane would have objected to the height and out-of-scale nature of this and similar developments,” agrees Anthony Flint, a fellow at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the author of Wrestling with Moses: How Jane Jacobs Took on New York’s Master Builder and Transformed the American City. “She was all about a sense of scale and the gospel of the street.” Jane’s son James Jacobs, who lives in Toronto, said that his mother had told him how much she disliked the project. “I think she would have tried to organize the neighborhood to stop it,” he says.

As City Journal’s Nicole Gelinas and journalist Norman Oder, who writes the Atlantic Yards / Pacific Park Report, have documented, the Atlantic Yards / Pacific Park project also has been marked by a farcically unaccountable review process and broken developer promises. Most of the “community” groups that signed a 2005 agreement with Ratner, publicly backing the development, for example, received money for their support, and their claim to speak for neighborhood residents was questionable. Forest Ratner’s chief executive officer noted that the firm had “funding obligations and commitments” to some eight community organizations; only two were incorporated when negotiations with the developer began, and almost none had an established track record. And as his costs rose and the financial crisis hit, the politically connected Ratner demanded—and got—ever more concessions from the city, from larger tax breaks to reductions in the number of people he was required to employ and the number of affordable rental units he was to include in the development.

New York State continues to file eminent-domain petitions in the Brooklyn Supreme Court and fight apartment owners and businesses over compensation for their property. The first apartments were supposed to go on sale last year in the project’s Tower B2, proclaimed the world’s tallest modular apartment building, but engineering and other problems have delayed the opening. Recently, 278 project condos went up for sale in a nearby 17-story building in Prospect Heights. Studios start at $550,000, with four-bedroom flats and penthouses advertised at $5.5 million. The 2,250 affordable rental units remain unfinished.

Yet Mitchell L. Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University and former advisor to Mayor Michael Bloomberg, is willing to defer judgment for now on Pacific Park. “It is not clear what will happen to the area surrounding the Barclays Arena,” he says, allowing that the arena itself “has been a great success.” And Moss argues that too many of Jane Jacobs’s devotees mischaracterize her as a dogmatic preservationist. “Preservationists have destroyed Bleecker Street,” he said, referring to the major shopping and dining street in Greenwich Village, “by creating a preserve where tourists and the very rich find the city’s most expensive gelato and high-end boutique chains,” he said. “She would have been more unhappy with Bleecker Street than Atlantic Yards.”

By contrast, a project that might well have gained Jacobs’s support, despite its vast scale, is Hudson Yards, the ambitious development on Manhattan’s West Side, between 42nd and 32nd Streets and from the Hudson River to Tenth Avenue. Former mayor Michael Bloomberg committed $2 billion in 2006 to extend the Number 7 subway line from Times Square south and west to 34th Street and Eleventh Avenue and link up with the Hudson Yards residential, office, and retail complex, one of the mayor’s signature development efforts. After years of missteps and blocked earlier schemes to improve the area—including the construction of Westway, a multilane expressway along the Hudson River, and a giant stadium that Bloomberg endorsed in 2012 to entice the Olympics to New York—New York State and City, working with one of the city’s biggest developers, Related Companies, which bid competitively for part of the tract, may finally have gotten it right.

Hundreds of construction workers are now building four office towers, a hotel, a public observation deck and retail center, and at least a half-dozen residential buildings west of Tenth Avenue. A 52-story office tower is rising at Tenth Avenue and 30th Street, along with another developer’s 67-story skyscraper, 1 Manhattan West, at 33rd and Ninth Avenue. The shopping mall along Tenth Avenue will span 1 million square feet and host a Neiman Marcus department store. West Side development has been generating so much money in fees and taxes, officials recently told the New York Times, that the city won’t have to dip in to its general fund to finance the planned park and subway line.

A combined effort in which the developer is the ground lessee from the MTA, Hudson Yards is eventually supposed to have 14 skyscrapers, containing 18 million square feet of new office, retail, and residential space, and include cafés, markets, bars, a hotel, and a “culture shed.” About 5,000 new units—1,200 of them affordable—will be added to the city’s housing stock. The plan also encompasses a public school and 14 acres of public, open space. “The community board and residential groups with which we consulted felt strongly about the need for more culture, a public school, day care—and we committed to keeping 50 percent of the acres open sky,” says Jay Cross, president of Related Hudson Yards, which is leading Related’s development of the 26-acre site. “With so much open space, we need to build high and densely.” The towers, he said, will reach 30 to 90 stories.

Unlike Atlantic Yards, Cross explains, Hudson Yards was supported by the community because the rail yard that runs through it was truly blighted. And because the area was relatively deserted, the state didn’t have to use (or abuse) eminent domain to dislodge residents and businesses. The developer wants to keep the smaller, squatter structures closer to the water, so that the buildings will seem to rise from the shoreline in a reverse cascade. “Everything below 150 feet is very important,” Cross says. “If a building is well designed, the pedestrian should be unaware of whether it is 40 or 60 stories high.”

Cross, another developer who praises Jacobs and knew her in Toronto, said that he wasn’t certain what she would think about Hudson Yards, “given its size.” “But the world and New York have changed dramatically since her earlier battles,” he notes. “The scale of today’s New York is very different.” With the housing supply constrained not only by regulations—everything from rent control to permitting makes it expensive to build all but high-end living space in the city—but also by the city’s density and tight geographical boundaries, building vertically is essential to easing the housing shortage, as is the renewal and expansion of smaller-scale neighborhoods in the outer boroughs.

But just how high should Gotham go? The city that Jane Jacobs left after her victory over Moses has indeed changed dramatically. Crime has been dramatically reduced, not only saving lives but also emboldening New Yorkers with confidence in walking around the city. (“The bedrock attribute of a successful city district,” Jacobs wrote, “is that a person must feel personally safe and secure on the street among all these strangers.”) The city itself is growing—and seemingly destined to continue doing so. New York’s population increased from 7.3 million in 1990 to 8.3 million in 2012, exceeding its previous peak in the 1950s by about 400,000. Growth on the West Side has been particularly pronounced—the area has added 18 percent to its population between 2000 and 2010. The population surge has boosted demand for housing, transport, and other services, putting even more pressure on housing costs. “New York, like San Francisco, is now a wonderful place to be,” Cross says.

Foreigners think so, too, which is why so many have flocked to One57, the first of seven new super-tall, super-thin, super-expensive condominium buildings arising in midtown between 53rd and 60th Streets—four of them on 57th Street alone. (Five more are planned in the area.) Day by day, writes Paul Goldberger, 57th Street is becoming “less of a boulevard defined by elegant shopping and more like a canyon lined by high walls.” The most talked-about—and, by many, hated—of the new mega-towers, though, is 432 Park Avenue, an 89-story spire at 56th Street and Park, built on the former site of the Drake Hotel. Designed by the modernist architect du jour, Rafael Viñoly, it is the tallest residential structure in the Western Hemisphere and now dominates the New York skyline. Its “thin looming presence,” architecture critic Martin Filler observes in the New York Review of Books, “seems to follow you around like a bad conscience.”

Advances in engineering and material strengths have made these “spindles” possible, and demand for them—at $8,000 to $10,000 per square foot—seems destined to grow. While New York is a vertical city that takes pride in its iconic skyscrapers, critics have charged that these structures have more to do with greed than with architectural distinction. Layla Law-Gisiko, a member of Community Board 5, who headed a “Sunshine Task Force” on the spindles, has called for a moratorium on any buildings rising higher than 600 feet. She argues that New York’s zoning laws haven’t kept pace with the breakthroughs that make the construction of these architectural “monstrosities,” as she calls them, possible. “There was no serious public review of these towers,” she complains, “and no transparency. Before the new skyline becomes a disastrous fait accompli, we need to decide whether and where we want to permit the construction of sky-rises that will cast a permanent shadow over roughly a third of Central Park.” Some 40 million people a year visit Central Park, she points out. “We need a serious, mandatory review process.”

An immigrant to New York, Law-Gisiko says it doesn’t particularly trouble her that many of these expensive units are getting snapped up by foreigners. But both she and the task force are disturbed by the secrecy surrounding who is buying what, since many owners have purchased units through anonymous corporations. While this same pattern has emerged in London, Paris, and other destination cities, partially empty buildings of this size (the owners are often absent) are about as far from Jacobs’s “eyes on the street” ideal as one could imagine. But it’s the buildings’ gigantism that would have most offended her. “Poor Jane,” says Law-Gisiko. “It’s hard to put a price tag on the aesthetic damage.”

Jacobs warned about the impact on cities of what she called “cataclysmic money”—massive, sudden surges of capital and the “oversuccess that such infusions can lead to,” observes Anthony Flint. “New York would do well to ensure at a minimum that property owners in such structures pay their fair share of taxes,” he says. SL Green’s 1.6 million-square-foot office tower at One Vanderbilt, he notes, is a rare example of a developer agreeing to pay for improvements and maintenance of some of a big project’s surrounding infrastructure—in this case, financing $220 million in subway improvements for Grand Central Terminal to help ease rush-hour overcrowding.

Jacobs didn’t envision every problem that would beset New York. She wrote her most influential work decades before New Yorkers were forced to confront the security challenges resulting from the September 11 terror attacks. Intimate, easily accessible streets, buildings, and spaces of the kind Jacobs loved are antithetical to the barricades, setbacks, and metal detectors now omnipresent in New York’s high-target buildings and venues.

And Jacobs might well have despaired about the possibility of preserving Greenwich Village–scale life in a city that global mobility and market forces have made a sought-after destination. While much about today’s New York would please her—its low crime, cleaner air and water, survival of myriad small businesses despite high taxes and burdensome regulations, and the steady reclamation of once-blighted neighborhoods by newcomers of widely varied ethnicity and income levels—she was increasingly distressed by the state of urban America by the time of her death, in 2006, at 89. Her final, bleak book about cities and the future is called Dark Age Ahead. Yet the dynamism and vitality that she so valued and associated with truly great metropolises are more present in today’s New York—thanks in part to her—than in the city she fought to save. Still, the city’s aging infrastructure, the hollowing out of an urban middle class, and the wildly rising costs of living and doing business here present challenges to New York’s future that might one day make her battle with Robert Moses pale by comparison.

But it is too easy to conclude from Jacobs’s loving descriptions of old streetscapes and community life that she would have favored a planning regime to ensure that new construction should take only that form— or that all older buildings and neighborhoods should be preserved exactly as they are. Fundamentally, Jacobs favored a decentralized approach to building and renewing the city. Her argument with government-led urban renewal wasn’t just about its effect on the kinds of neighborhoods that she enjoyed; it was also about the process itself. In other words, the aesthetic Jacobs should not be confused with Jacobs the urban non-planner. When reflecting on aspects of contemporary New York that she might have liked or disliked, we should keep this dynamic in mind.

Jane Jacobs is missed, observes Jason Epstein, her longtime publisher and friend (and my husband), because she was adamantly nonideological, with both Left and Right finding inspiration in her work. The arguments she mustered against soulless high-rises, the destruction of neighborhoods in the name of slum clearance and urban renewal, and the blasting of highways through the heart of a city seem blindingly obvious to us now. They weren’t at the time, of course, which made her often cautious, pragmatic advice seem revolutionary. The challenge of ensuring continued vibrancy of space so much in demand in today’s New York is one that Jacobs now leaves to us.