For decades, Western culture has been reluctant to assign an inherent value or a purpose to art—even as it continues to hold art in high esteem. Though we no longer seem comfortable saying so, our reverence for art must be founded on a timeless premise: that art is good for us. If we don’t believe this, then our commitment—in money, time, and study—makes little sense. In what way might art be good for us? The answer, I believe, is that art is a therapeutic instrument: its value lies in its capacity to exhort, console, and guide us toward better versions of ourselves and to help us live more flourishing lives, individually and collectively.

Resistance to such a notion is understandable today, since “therapy” has become associated with questionable, or at least unavailing, methods of improving mental health. To say that art is therapeutic is not to suggest that it shares therapy’s methods but rather its underlying ambition: to help us to cope better with existence. While several predominant ways of thinking about art appear to ignore or reject this goal, their ultimate claim is therapeutic as well.

Art’s capacity to shock remains for some a strong source of its contemporary appeal. We are conscious that, individually and collectively, we may grow complacent; art can be valuable when it disrupts or astonishes us. We are particularly in danger of forgetting the artificiality of certain norms. It was once taken for granted, for instance, that women should not be allowed to vote and that the study of ancient Greek should dominate the curricula of English schools. It’s easy now to see that those arrangements were far from inevitable: they were open to change and improvement.

When Sebastian Errazuriz created dollar signs out of ordinary street markings in Manhattan, his idea was to jolt passersby into a radical reconsideration of the role of money in daily life—to shake us out of our unthinking devotion to commerce and to inspire, perhaps, a more equitable conception of wealth creation and distribution. (One would completely misunderstand the work if it were taken as an encouragement to work harder and get rich.) Yet the shock-value approach depends upon a therapeutic assumption. Shock can be valuable because it may prompt a finer state of mind—more alert to complexity and nuance and more open to doubt. The overarching aim is psychological improvement.

Shock can do little for us, though, when we seek other adjustments to our moods or perceptions. We may be paralyzed by doubt and anxiety and need wise reassurance; we may be lost in the labyrinth of complexity and need simplification; we may be too pessimistic and need encouragement. Shock is pleasing to its adherents in its assumption that our primary problem is complacency. Ultimately, however, it is a limited response to impoverished thinking, timid or ungenerous reactions, or meanness of spirit.

Another way of addressing these shortcomings is to pursue a deeper understanding of the past. Vittore Carpaccio’s painting The Healing of the Madman offers a rare visual record of the Rialto Bridge—then still made of wood—before it was reconstructed, so it has much to teach us about the architecture of Venice circa 1500. It’s also highly instructive about ceremonial processions, the prominent civic role of religion (and its intersection with commerce), how patricians and gondoliers dressed, how ordinary people wore their hair, and much else. We also gain insight into how the painter imagined the past; the ceremony depicted took place over 100 years before the picture was painted. We learn something about the economics of art—the image is part of a series commissioned by a wealthy commercial fraternity. In a less scholarly way, the richness with which a past era becomes visually present allows us to imagine what it would have been like to clatter across the wooden bridge, to be rocked along the canals in a covered gondola, and to live in a society in which belief in miracles was part of the state ideology.

We value historical information of this kind for various reasons: because we want to understand more about our ancestors and how they lived and because we hope to gain insight from these distant people and cultures. But these efforts lead back, eventually, to a single idea: that we might benefit from an encounter with history as revealed in art. In other words, the historical approach does not deny that the value of art is ultimately therapeutic—it assumes this, even if it tends to forget or dismiss the point. Hence the irony (to put it gently) of scholarly resistance to the idea of art’s therapeutic benefit. Erudition is valuable only as a means to an end, which is to shed light on our present needs.

Another approach sees art as a succession of discoveries or innovations in the representation of reality. In this almost scientific way of evaluating art, we elevate artists who pioneered new techniques, much as we prize explorers and inventors from history (“Who discovered America?” “Who built the first steam engine?”). Leonardo da Vinci is crucial, in this view, because he was an early adopter of sfumato, an artistic technique for showing shapes without using outlines.

Likewise, Paul Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire is seminal for being one of the earliest works to emphasize the flat surface of the canvas. In his image of the mountain as seen from Les Lauves, his property near Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne uses blocks of paint to symbolize shrubs—though they are, on closer examination, equally colored marks forming an abstract pattern. (This is most apparent if the top half of the painting is covered.) We are presented not with the illusion of three-dimensional space but with the admission that this is a two-dimensional work.

Cézanne’s approach is so familiar to sophisticated enthusiasts that it seems almost embarrassing to point out that his technique explains little about the work’s value to us. The worth of an invention can be assessed externally only in terms of the genuine benefits that it brings. Technical discussions reveal only the changes in methods of design or production. The new ways are not good in themselves; they are good only if we have reason to believe that they are better than the old. Hence the technical view of art has a buried assumption: it presupposes that the works in question are beneficial to us. It does not explain why this should be so but, like the historical approach, takes this for granted. Technical advances are valuable insofar as they bring new, or enhanced, therapeutic resources to the art form.

If one agrees with Hegel that art is the sensuous presentation of the idea (or ideal), it remains to be explained why such a presentation is valuable. What is the nature of our troubles or aspirations, such that art is something that we need?

The therapeutic thesis is not simply another idea about art’s value. It homes in on the only area in which such value could be explained: art’s capacity to improve our lives. Art can be:

A corrective of bad memory: Art makes the fruits of experience memorable and renewable. It is a mechanism to keep our best insights in good condition and make them publicly accessible.

A purveyor of hope: Art keeps pleasant and consoling things in view, fortifying us against despair.

A source of dignified sorrow: Art reminds us of the legitimate place of sorrow in a good life, so that we recognize our difficulties as elements of any noble existence.

A balancing agent: Art encodes with unusual clarity the essence of our good qualities; it holds them before us to help rebalance our natures and direct us to our best possibilities.

A guide to self-knowledge: Art can help us identify what is central to life but difficult to put into words. Visual art helps us recognize ourselves.

A guide to the extension of experience: Art is an immensely sophisticated accumulation of experience, presented to us in well-organized forms. We can hear the voices of other cultures, extending our notions of ourselves and the world. At first, much art seems merely “other”—but we discover that it contains ideas that we can make our own, in ways that enrich us.

A tool of re-sensitization: Art saves us from our habitual disregard for what is all around us. We recover our sensitivity and look at the familiar in new ways. We are reminded that novelty and glamour are not the only solutions.

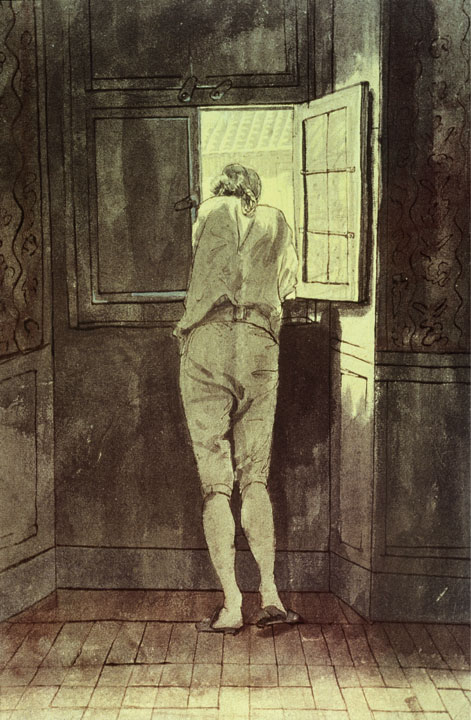

Consider, for example, Tischbein’s Goethe at the Window of His Roman Apartment. We see the great man from behind: a slipper falls casually from his foot as he leans out, and the dim coolness of the room and the bright sunshine of the street make a powerful contrast. Some might see in this work an attempt to preserve the lessons learned on holiday. Away from home and work, in the warm South, Goethe became (like most travelers) a slightly different—and, in some ways, better—version of himself. The drawing attempts to memorialize the good version of the self and make that more prominent and more readily accessible when one has returned to familiar surroundings. The point is not so much to recall that Rome was interesting as to encapsulate who one became there. Goethe could hardly take the Italian weather back to Weimar; what he could do was hold on to the insight into his nature and needs that he gained while away. Hence it is a pity if one is more likely to encounter such images on the walls of a pensione in Trastevere than in a subway station in a metropolis, where its meditative qualities are more needed.

In Rocky Reef on the Sea Shore, Caspar David Friedrich uses a striking, jagged rock formation, a spare stretch of coast, the bright horizon, faraway clouds, and a pale sky to induce a mood. We might imagine walking in the predawn hours, after a sleepless night, on the bleak headland, away from human company, alone with the basic forces of nature. The lower portion of the sky is formless and empty, a pure silvery nothingness, but above it are clouds that catch the light on their undersides and pass on in their pointless, transient way, indifferent to our concerns.

The image of nature does not refer directly to human relationships or to the stresses and tribulations of daily life. Its function is to give us access to a state of mind in which we are acutely conscious of the largeness of time and space. The work is somber, rather than sad; calm, but not despairing. And in that condition of mind—that state of soul, to put it more romantically—we find ourselves, as so often with works of art, better equipped to deal with our intense, intractable, and particular griefs.

The idea that art’s value should be understood in therapeutic terms is not new. In fact, it is the most enduring way of thinking about art, having its roots in Aristotle’s philosophical reflections on poetry and drama. In the Poetics, Aristotle argued that tragic drama can elevate how we experience fear and pity—two emotions that help shape our experience of life. The broad implication is that the task of art is to help us flourish, to be “virtuous,” in Aristotle’s special sense of that word: that is, to be good at living, even in challenging circumstances.

This understanding of art has been in abeyance in recent decades, but it is, I believe, the only plausible way of thinking about art’s value. Other approaches, as we have seen, must tacitly assume it, even when they deny it. To consider art from a therapeutic point of view is not to abandon profundity but to embrace it and to return art to a central place in modern culture and modern life.