One of the many crises that overwhelmed David Paterson’s brief, hapless term as governor of New York was a surge in Medicaid costs. Every recent New York governor has tried but failed to rein in Medicaid. Yet Paterson’s opportunity to address the problem appeared promising. Government spending had to be cut during the 2009 budget cycle because of that year’s historic collapse in revenues. Accordingly, Paterson proposed $3.5 billion in cuts to the state’s Medicaid program—the second-greatest burden on New York taxpayers, after K–12 education—and sought to shift monies away from inpatient hospitals to less expensive outpatient clinics. Hospitals would have seen a revenue reduction of less than 2 percent.

But Medicaid is one of the primary sources of funding for the hospitals employing workers from 1199SEIU, the powerful hospital and nursing-home employees’ union. The union responded to Paterson’s proposal with an ad blitz extraordinary in its cost—$1 million per week, for a month of television and radio spots—and viciousness. One commercial featured a blind man in a wheelchair saying, “Why are you doing this to me?” Paterson, who is blind, retreated, opting instead for tax increases and deeper cuts to other programs. The episode illustrated how far 1199SEIU will go to protect its interests. The union enjoys a reputation as New York’s most formidable organized interest, largely due to its success in thwarting almost every effort to discipline Medicaid’s runaway expenditures.

The union’s clout can be assessed by several measures: the sheer size of its membership, its spending on campaigns and lobbying, and the depth and breadth of its connections with New York’s ruling elite. With well over 300,000 members in Massachusetts, Maryland, Florida, Washington, D.C., and New York (where over half of that total resides), 1199SEIU is the largest union local in the nation, and possibly the world. (The union’s current name stems from 1199’s merger with the Service Employees International Union, or SEIU, in 1998. For brevity’s sake, we will refer to that entity as “1199” throughout this article, except when referring to the national SEIU.) The contract terms established by 1199 also set the standard for the 10,000 workers in the city’s Health and Hospitals Corporation represented by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) District Council 37. Thanks to state laws that allow unions to deduct dues automatically from employees’ paychecks, the union’s massive membership means a massive treasury. According to its most recent filings with the U.S. Department of Labor, 1199’s annual budget is about $185 million, derived mostly from members’ $18 to $75 monthly dues. Adjusted for inflation, annual revenues between 2002 and 2014 grew from $118 million to $180 million as the union’s membership ballooned from 225,000 to 354,000, mainly through mergers with other unions.

Deploying its members and financial resources, 1199 has branched out to support other “progressive” causes, including tax increases, gay rights, climate change, and an expansive immigration policy. It has helped underwrite “living wage” campaigns, including the “Fight for $15” fast-food workers’ movement, and lent support to the recent antipolice protests in New York City and elsewhere. Now that 1199’s longtime friend and former employee, Bill de Blasio, has been elected mayor, the union’s power is at an apogee, especially at the city level. The union’s continued dominance not only thwarts prospects for health-care reform in New York; it also drowns out any sense of proportion in public discourse, particularly in the city.

The rise of 1199 from a small union of pharmacists and drugstore clerks to the political force that it is today should be seen as part of the decades-long shift in organized labor’s power base from private industry to government. In 1932, when 1199 was founded, the dominant labor unions represented workers in manufacturing and the skilled trades. As labor historian Joshua Freeman has noted, “1199’s expansion into hospitals and nursing homes was, with the exception of the unionization of public employees, New York labor’s most important organizing success of the post–World War II era.”

The expansion took place mostly during the 1960s. Having successfully organized the vast majority of drugstores in the city by 1958, union president Leon Davis, a Russian-born drugstore clerk and onetime member of the American Communist Party, set out to organize New York’s “voluntary” hospitals. Founded in the nineteenth century as nonprofit public charities with a religious orientation and dedicated initially to caring for the indigent, the voluntary hospitals eventually began seeking out government subsidies and paying customers to diversify their revenue streams. During the 1920s, observe historians Sandra Opdycke and David Rosner, patients’ fees accounted for 69 percent of the voluntary hospitals’ revenue, though fiscal stability remained elusive for them. The hospitals’ boards continued to take their charitable mission seriously. They resisted unionization, believing that the services that hospitals provided were too vital to submit to union demands, let alone to permit slowdowns or strikes. The hospitals also feared that unionization threatened their already-uncertain fiscal situation. This antiunion mind-set helped make health care the “quiet zone” of labor relations for generations.

Undaunted, Davis set out to organize workers at these hospitals and then threaten strikes if management refused to acknowledge the union. His first conquest was Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, which 1199 organized in 1958. Seven other voluntary hospitals caved, following a 46-day strike against them that began in May 1959. Nonprofit hospitals had been exempted from labor law requiring private employers to recognize union representatives as workers’ exclusive bargaining agents. But an 1199-led strike in 1963 forced Republican governor Nelson Rockefeller to sign legislation that incorporated New York City’s nonprofit hospitals into the State Labor Relations Act. In 1965, this legal authority was extended statewide. (1199 had endorsed Rockefeller for governor in 1962.) According to Leon Fink and Brian Greenberg’s comprehensive history, Upheaval in the Quiet Zone, by the end of the 1960s, three-quarters of the local hospital labor force was unionized and 1199 had quadrupled its membership.

From these early organizing struggles, Davis left two key tactical legacies. The first was an appreciation for the benefits of ideology and symbolism. All of 1199’s 1960s-era campaigns were cloaked in the language of civil rights, an effective strategy, as most of the union’s members were black and Puerto Rican. Its “union power, soul power” rhetoric helped 1199 cultivate high-profile liberal supporters such as Eleanor Roosevelt, U.S. Senators Herbert Lehman and Jacob Javits, Martin Luther King (who called 1199 “my favorite union”), Thurgood Marshall, Malcolm X, the New York Times, and the then-left-leaning New York Post. Longtime Post columnist Murray Kempton once likened 1199 strikes to “wars of national liberation.”

Davis’s second tactical bequest was his discovery that the most effective way to win over hospital management was via government bailout. The turning point at Montefiore came when city government offered to raise the subsidy it had been providing for ward patients from $16 a day to $20. Similar deals were struck during subsequent organizing campaigns. A game emerged, in which 1199 would push management to the brink of a strike, and then city or state government would swoop in with an 11th-hour offer of funds to secure “labor peace.”

Davis’s tactics were honed further under Dennis Rivera, who led 1199 from 1989 to 2007. Rivera grew up middle-class in Puerto Rico and moved to New York in 1977; his first job on the mainland was as an organizer for 1199. Upon being elected union president, Rivera faced two challenges. Davis’s long-delayed retirement in 1982 had led to bitter factionalism among his successors. Rivera projected a calm, optimistic outlook that appealed strongly to members, and he sought to swell 1199’s ranks by enlisting a variety of local unions to join it. The other challenge was politicians’ growing need to contain health-care spending—especially for Medicaid. Rivera recognized that politics, more than collective bargaining, offered the means to pursue his members’ interests. This meant forging alliances with hospital management and the state Republican Party.

Rivera and the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA), which represented 175 hospitals and nursing homes in the city, began working together almost as soon as he became president. The partnership took concrete form with the creation of the joint Healthcare Education Project, which now forms the cornerstone of New York’s “medical industrial complex”: the coalition of unions, providers, and advocates that keep health-care costs high by promoting “institution-focused care” over less expensive home- and community-based options. Through this initiative, labor and management set out to pursue more government funds for themselves as an explicit policy objective. As Kenneth Raske, the head of GNYHA, put it, “government [held] the key to all our problems.” Under Rivera’s leadership, 1199 shifted its political efforts into overdrive. “[We took] the existing [union] culture of giving to political candidates and ramp[ed] it up to a whole new level,” explained Jennifer Cunningham, a top Rivera lieutenant. Cunningham attributed the union’s political success to “the ability to mobilize voters around a public policy issue, sophistication of materials, and frankly, a boatload of cash.”

Rivera’s alliance with the state Republican Party, which controlled the governorship and state senate throughout 1199’s surge to dominance in the 1990s, was equally shrewd. The 1199 leader used campaign funds and a personal touch to woo the Republican leadership, bonding with Joseph Bruno, senate majority leader from 1994 to 2008, over a shared love for horses and Bruno’s liberal sympathies on health-care policy. If both sides viewed this marriage as one of convenience, 1199 got the better of it. In 1995, GOP governor George Pataki’s first year in office, Republicans held 11 more state senate seats than Democrats; 20 years later, after falling into the minority in two of the four electoral cycles since 2008, their margin of majority control is just one seat.

As he deployed 1199’s resources to shore up New York’s medical and political establishments, Rivera also burnished his progressive bona fides, championing tenants’ rights, gay marriage, universal health care, and the withdrawal of the U.S. Navy from the island of Vieques, Puerto Rico. In the modern incarnation of 1199, forged in Rivera’s image, the line between politics and ideology becomes increasingly blurry, as does the distinction between power as a means and as an end in itself.

The union puts that power to a host of political uses, starting with state-level lobbying, which consumes by far the largest portion of its political budget. State filings show that 1199 and its affiliate, the Healthcare Education Project, have spent $30.7 million over the last decade, a sum that surpasses even the lobbying expenses of a perennial Albany powerhouse, the New York State United Teachers. Some 1199 lobbying efforts have also been financed by voluntary contributions from members and, in the late 1990s, “excess” employer-pension contributions (see sidebar). Anyone who doubts the union’s lobbying might should consider its success in squaring off against the most formidable organized interests. In 1999, for example, when lobbying Albany to hike cigarette taxes to fund a Medicaid expansion, 1199 and GNYHA spent 14 times as much as the Philip Morris Corporation, which opposed the increase. The union prevailed.

The union supplements its lobbying efforts with state-level political contributions, which have totaled $9.5 million since 1997, according to the National Institute for Money in State Politics. These “hard money” contributions to candidates and parties are striking not only for their size—1199 regularly ranks among the state’s top donors—but also for what they reveal about the union’s political opportunism. Over the years, the two largest recipients have been the New York Democratic Assembly Campaign Committee ($1,712,500) and the New York Senate Republican Campaign Committee ($1,594,300).

The union spends less locally on lobbying and electioneering, reflecting in part New York City’s tighter campaign-finance regulations and the fact that most major health-care policy decisions are made in Albany. Still, 1199 ranks as the top donor in each of the last three citywide election cycles. It has made good use of the new campaign-finance latitude afforded by Citizens United—which struck down restrictions on political spending by corporations and unions—and related high court decisions, devoting about $440,000 to “independent expenditures” in addition to the $150,000 it gave directly to candidates. Last year, the union donated $250,000 to “Campaign for One New York,” Mayor de Blasio’s “dark-money” fund that’s now bankrolling much of his “Progressive Contract with America.”

Another vital component of 1199’s extraordinary influence is its vaunted ground operation, including get-out-the-vote efforts that don’t technically count as a campaign contribution. The union claims that 100,000 of its members in New York City are registered Democrats. That sum happens to be almost exactly the margin by which Bill de Blasio, 1199’s preferred candidate, defeated his closest rival, Bill Thompson, for the Democratic nomination for mayor in 2013. In support of de Blasio, 1199’s canvassers are said to have knocked on tens of thousands of doors. The union’s finances and organization give it an enormous advantage in phone-banking, distributing flyers, and other retail campaigning tactics that have proved decisive in this era of low voter turnout in New York City.

Another vital cog in the 1199 machine is the Working Families Party (WFP). Founded in 1998 by 1199 and several other unions and activist networks, the WFP is a creature of New York’s “fusion” electoral system, through which minor parties can cross-endorse major-party candidates. In this system, Democrats who want to avoid a challenger running to their left must secure the WFP’s endorsement. In addition to the leverage it wields through its ballot line, the party’s 40-person full-time staff and 500 paid election canvassers have made it the most important third party in New York, especially at the city level. The WFP has also effectively developed its own legislative bloc in the city council, the Progressive Caucus, to which 19 of the 51 council members now belong. In 2014, 1199 was the WFP’s largest source of financial support.

Its political might has also made 1199 into a talent farm for the Democratic Party’s liberal wing. Take the impressive career of Jennifer Cunningham, a well-connected advisor in Democratic circles, once described by the New York Post as “the most powerful woman in Albany.” She joined 1199 after earning her spurs in the political-affairs office of Victor Gotbaum’s AFSCME District Council 37, the largest pure government union in New York City. Cunningham also worked as a staffer for Sheldon Silver, the former longtime speaker of the state assembly, and she’s the ex-wife of current attorney general Eric Schneiderman. She advised Christine Quinn in her campaign for mayor and Andrew Cuomo in his gubernatorial campaign, even as some of her colleagues lent their services to more left-wing candidates. Now with the prominent lobbying and consulting firm SKDKnickerbocker, Cunningham has advised Governor Cuomo on his Medicaid Redesign Team, tasked with cutting payments to hospitals.

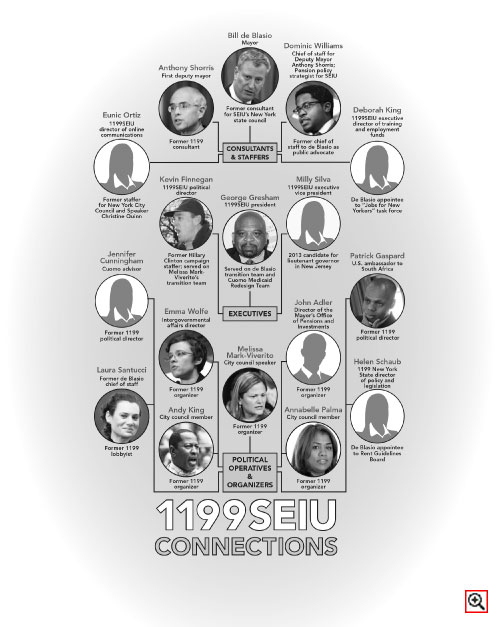

The 1199 alumni network extends far beyond New York. Its most distinguished member is Patrick Gaspard, currently the Obama administration’s ambassador to South Africa. A former colleague of Cunningham’s and one of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s close friends, Gaspard earlier served as Obama’s White House political director and as executive director of the Democratic National Committee. Many 1199 operatives also go on to work for the national SEIU, whose president, Andy Stern, was President Obama’s most frequent White House visitor during his first 100 days in office.

New York City is 1199’s true power center, however. It’s hard to overstate the significance of 1199 to the so-called progressive movement that now controls almost every major city office. City council speaker and leader of the Progressive Caucus Melissa Mark-Viverito is a former organizer for 1199, which has played an active role in her career from the beginning. The union suggested that the Puerto Rican–born and Columbia University–educated heiress move from Greenwich Village to East Harlem to establish a political base. To help her launch her campaign for the city council speakership, 1199 threw a lavish party in San Juan. The union’s political director, Kevin Finnegan, served on Mark-Viverito’s transition team when she became speaker.

Having once been on either SEIU’s or 1199’s payroll appears to be almost a prerequisite for working in the de Blasio administration. Many members of the mayor’s inner circle, including de Blasio himself, were once employed by SEIU or 1199. First Deputy Mayor Anthony Shorris was an 1199 consultant, and de Blasio’s former chief of staff, Laura Santucci, was an 1199 political aide who went on to work for the Democratic National Committee. Emma Wolfe, de Blasio’s deputy campaign manager and now director of intergovernmental affairs for New York City, has worked for 1199 and the Working Families Party. In January, de Blasio appointed John Adler director of the Mayor’s Office of Pensions and Investments and chief pension investment advisor. Adler spent 23 years with SEIU, as an 1199 organizer and later as a retirement- and pension-policy official. His appointment likely stemmed from his 1199 connections—it couldn’t have owed to his financial wizardry: the union’s pension fund recently showed up on the federal government’s watch list of endangered multiemployer funds.

De Blasio himself may owe his mayoralty to 1199, the only major union to back him during the Democratic mayoral primary. The 1199 endorsement was essential in catapulting de Blasio into contention for the nomination—and the mayoralty. The union’s 150-member executive council supported de Blasio in a unanimous vote. After being elected, de Blasio named current 1199 president George Gresham, a longtime friend, to his transition team.

In the same way that Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s background as a prosecutor contributed to the law-and-order ethos of his administration, the activist cast of the de Blasio administration finds its roots in the progressive union culture of 1199. As the liberal- and labor-friendly New York Times put it: “In Bill de Blasio’s City Hall, it seems more and more, there is only a left wing.” What distinguishes New York’s progressive establishment from those in other cities is its political success—which would not have been possible without 1199’s financial and organizational support.

How 1199 Turned Its Pension Fund into a Slush Fund

Critics and supporters alike tend to agree that 1199 has done well by its members, but this conclusion is suspect with regard to pensions, where union leadership’s political ambitions have jeopardized members’ retirement security. The union oversees four multiemployer pension funds that have promised $20 billion in benefits to 365,000 participating members. One of these, the Health Care Employees Pension Fund, is the sixth-largest multiemployer plan in the nation. The pensions draw their funding from employer contributions negotiated between the union and employers—in the case of New York City 1199 members, the League of Voluntary Hospitals (LVH)—and investment returns.

In 1999, as a soaring stock market caused its pension plans to be overfunded, 1199 and LVH decided to get creative with the surplus. They used $135 million in employer contributions to finance an early-retirement program and another $10 million to fuel 1199’s epic (and successful) lobbying effort to expand Medicaid that year, a victory that cemented the union’s status as an irresistible force on state health-care policy. At the time, these moves seemed safe: the Health Care Employees Pension Fund was flush.

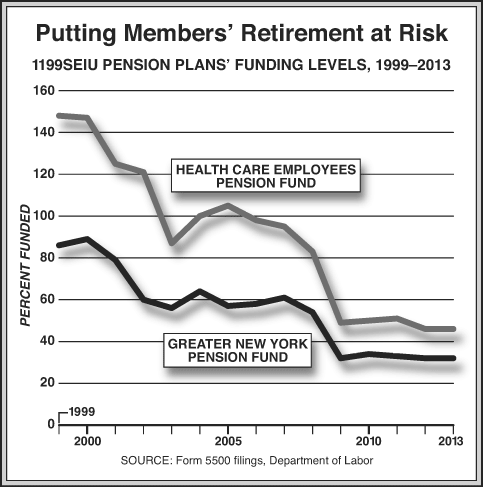

But now the bill has come due. In 2009, both the Health Care Employees Pension Plan and 1199’s Greater New York Plan were certified as “critically” underfunded under the terms of the federal Pension Protection Act. Greater New York only recently left critical status; both plans’ funding levels remain dramatically lower than they were during the late 1990s (see graph).

Critically underfunded pension systems face a greater possibility of failure and, ultimately, benefit reductions, than responsibly managed systems. In fact, newer 1199 hires have already seen their benefits reduced under the terms of the federally mandated “rehabilitation plan” drawn up to address the funding shortfall. And the massive contribution increases that 1199 has negotiated with employers have reduced the amount of money available for take-home pay. Thus, newer 1199 workers are seeing lower salaries and less generous benefits.

Other union-run multiemployer pension plans are in trouble nationwide, but 1199’s pension mismanagement stands out for being, at least in part, the result of political ambitions. While political concerns shape how unions run pension funds in many ways—most notably, through shareholder activism—1199’s decision to divert $10 million in pension contributions for lobbying expenses was a truly cynical move, even by organized-labor standards. That $10 million wasn’t the key cause of the pension shortfalls, but it offered a powerful demonstration of where the union’s priorities lie.

–Stephen Eide

The union’s strength has grown in direct proportion to the importance of health care to New York City’s economy. Between the mid-1960s and 2000, the period when 1199 began asserting its dominance, New York City gained 69,000 hospital jobs, a stunning 80 percent increase. During this same period, growth in government jobs was comparatively modest (22 percent) and manufacturing employment, the traditional mainstay of both the city economy and union strength, declined by 70 percent. At present, six of New York City’s top ten private-sector employers are health-care providers. When it was first organized, Montefiore had 900 employees. Now it has more than 20,000.

While 1199 has done well by its members—boosting their pay, benefits, and job security—it imposes diffuse costs on the public. The union’s vested interest in elevated levels of government health-care spending has had negative policy consequences over the years, particularly with respect to Medicaid, which supports, on average, one-third of the annual revenues at the five largest medical centers in New York City, all of which employ 1199 members. (Another third, on average, comes from Medicare.) According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, New York State spent $54 billion on Medicaid in 2013, more than one-third of the state budget and the second-highest amount among the states (after California, which has nearly twice as many people). New York spends more on Medicaid than Texas and Florida combined. The state spends so much because it enrolls so many people—6.2 million today, up from 2.7 million in 1995, during a period of near-stagnant population growth—and because it allocates Medicaid dollars using complex reimbursement formulas that favor inpatient hospitals and nursing homes—more expensive modes of health-care delivery than outpatient clinics and home care.

Favoring hospitals and nursing homes tends to favor health-care providers—including 1199 members—over patients. The goal of health-care policy should be to make people healthier, but the high price tag of New York’s health-care system has never correlated with its performance. New York ranks 19th in the nation in the quality of care, according to the Commonwealth Fund, though it spends more on a per-capita basis than any other state. In all of its health-care policy advocacy, 1199 has held to the position that what’s good for union members is good for the public. As one issue of its monthly newsletter put it, “Saving our hospitals isn’t just about jobs, but also about healthcare for the people.” But while making health-care jobs some of the most stable and secure in New York, 1199’s advocacy efforts helped create and perpetuate an overly expensive and inefficient health-care system.

Indeed, over the last two decades, 1199 has perfected a brand of politics that allows the union to get most or all of what it wants from New York governors—either by entering into mutually beneficial alliances or by organizing to quash reform plans that might be adverse to its members. George Pataki entered the governor’s mansion in 1995 with bold plans for health-care reform, which focused on getting control of Medicaid costs. “We have learned from our experience with Medicaid that more spending does not mean better care,” he said. But by the time of his final State of the State address in 2006, Pataki had abandoned talk of fiscal discipline, defining better care as expanded enrollment in government health-insurance programs. Pataki’s reversal was due entirely to pressure from 1199, which opposed him in his initial bid for office in 1994 and remained neutral in his 1998 reelection campaign against Peter Vallone. But by 2002, pleased with the governor’s evolution, the union endorsed him outright.

One of 1199’s most celebrated victories came in 1999, when an extraordinary $13 million lobbying campaign persuaded lawmakers to spend over $1 billion to expand Medicaid through a program called Family Health Plus, which would extend coverage to 600,000 previously uninsured adults. The union paid its lobbying bill by redirecting money from the 1199 pension fund, which was, at the time, overfunded.

An even more blatant example of union featherbedding came shortly after September 11, 2001, when Pataki and 1199 president Rivera negotiated a secret pact (later ratified by the state legislature) that set aside $1.8 billion in pay raises for health-care workers. In exchange, Pataki got his first 1199 endorsement. The dealmakers counted on dubious funding sources to pay for the new obligations, which included the hope that Washington would increase its contributions to the state’s Medicaid program by $4.5 billion, an expected $1 billion from the conversion of nonprofit insurer Empire BlueCross BlueShield into a for-profit company, and a cigarette-tax hike. But the federal monies failed to come through, the proceeds from the insurer conversion took seven years to materialize, and cigarette-tax proceeds declined as more people quit smoking.

The Empire BlueCross BlueShield conversion itself “violated perhaps every civics lesson in how public policy should be made,” says University of California at Berkeley health-policy analyst James C. Robinson. In other states, the profits from similar conversion deals were used to endow independent charitable foundations that support scientific inquiry and underwrite health care for the indigent. By contrast, New York expropriated the proceeds of one of the most lucrative health-insurance IPOs in American history and then used the money to subsidize hospitals and underwrite worker raises—both goals of 1199. Health-care advocates rightly questioned how boosting union workers’ salaries improved public health, particularly for the poor.

Given the Medicaid squeeze on the state budget, Pataki’s successor, Eliot Spitzer, tried to turn the tables on 1199 after he took office in 2007. Unlike Pataki, Spitzer rejected the concept of Medicaid as a union jobs program. At a breakfast meeting attended by hospital and labor leaders, Spitzer delivered a hard-hitting presentation that branded 1199 and GNYHA “guardians of the status quo.” In response to a proposal by the governor to impose cuts on hospitals and nursing homes, 1199 ran a multimillion-dollar ad campaign that sank Spitzer’s approval rating. Union ally Joseph Bruno, in control of the Republican Senate, staked out a position to the left of the governor; in the end, only a quarter of Spitzer’s proposed cuts went into effect.

Governor Andrew Cuomo has enjoyed better relations with 1199 than those of his predecessors, including Pataki, and thus 1199 has stood by him, even as he battles with most of the state’s other major public-employee unions, especially the teachers’ unions. After taking office in 2011, Cuomo met with Rivera and Raske to make a deal that would avoid another nasty public spending war over Medicaid. In exchange for finding ways to reduce Medicaid expenditures, Cuomo offered both men spots on his Medicaid Redesign Team. In addition, Cuomo promised to secure a five-year, $10 billion federal waiver that would offset the cuts in hospital payments with federal dollars. In effect, Cuomo demanded that the unions and the hospitals live within some limits but offered them stability if they did so. After taking the deal, 1199/GNYHA spent $6.8 million on a one-month blizzard of television spots and full-page ads in the New York Times to encourage the legislature and the public to support Cuomo’s proposals.

Cuomo’s collaborative strategy has pushed health-care policy back into the quiet zone and avoided the epic public battles with 1199 that his predecessors fought and lost. However, getting a grip on the state’s Medicaid spending, which had grown at more than twice the rate of inflation between 2000 and 2010, wasn’t cost-free. The union fought off cuts to nursing homes, secured a wage floor for home health-care workers while expanding their numbers, and pressured the governor to extend a tax increase on high earners to lessen the need for other changes. Cuomo also agreed to continue the Medicaid enrollment expansion that began under Spitzer and Paterson. In the long run, the governor’s cost-containment strategy hinges on getting Washington to grant New York more administrative flexibility under the Affordable Care Act.

To date, then, 1199 has achieved most of its ends when it comes to health-care policy. But the union remains focused on the continuing threat of hospital closings and consolidations, which got under way after the Berger Commission, appointed by Pataki near the end of his tenure, issued a report critical of “excess capacity” in New York’s health-care delivery. The commission found that the statewide hospital-bed occupancy rate was 83 percent in 1983 and just 65 percent in 2004 and that most nursing homes operate at a loss. This problem has led to gross inefficiency and endangered the quality of care. Insolvent hospitals can’t reinvest in equipment and staff, and a system with too many hospitals disperses expertise. The commission recommended closing nine facilities and downsizing dozens more across the state. The issue is particularly acute in New York City, where eight hospitals have closed since 2007. According to a 2011 report, “[a]lmost 30 percent of Brooklyn’s hospital beds are vacant on an average day.”

But while excess hospital capacity weakens the ability of the system as a whole to make people healthier, many hospital workers’ jobs depend on it. It is this threat to 1199’s interests that provides the backstory for one of the stranger episodes of the last mayoral campaign. During his quest for the Democratic nomination, de Blasio capitalized on the publicity he garnered when he was arrested at a protest organized by 1199 to stop the closing of Long Island College Hospital (LICH) in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn. LICH, which employed some 1,200 workers, had severe financial problems, many empty beds, and cost the state $10 million a month in subsidies. De Blasio simultaneously showed his solidarity with 1199 and bolstered his activist credentials. Nonetheless, the hospital wound up being sold to developers, who plan to demolish it and construct luxury condos, while retaining a small emergency clinic run by NYU-Langone. Activists now accuse de Blasio of using LICH as a political pawn.

In its own way, progressive ideology is just as vital to the modern 1199 as Medicaid revenues. Like other interest groups that rely on ideological incentives to enhance solidarity, 1199 must exaggerate threats to keep members engaged. Without uncompromising rhetoric and a sense of perpetual crisis, the union would risk seeing enthusiasm dwindle.

Today, 1199 flexes its muscle by providing logistical support to protests and networking among the powerful. Current president George Gresham, who dabbled in black nationalism as a young man, has kept the union at the forefront of racial politics. Under his stewardship, 1199, in partnership with other activist groups, has spearheaded rallies in Albany and Washington, D.C., to support the Dream Act for illegal immigrants. Most recently, 1199 has given a platform to the Justice League, the group that has led the protests against police in New York City and elsewhere. In December 2014, 1199 hosted at its midtown Manhattan headquarters a private conference between Mayor de Blasio and Justice League activists. Most commentators focused on the implications of de Blasio giving an audience to the protesters, but the meeting was more significant for what it revealed about how power works in New York: a hospital workers’ union was serving as the liaison between city government and the anti-cop Left.

The union’s rhetoric and muscle have crowded out political life in the city as effectively as Medicaid spending has choked off competing governmental priorities in the state budget. The lack of any real opposition to the so-called progressive movement in New York City has created a bizarre dynamic wherein elected officials often speak and act out against “the system”—which they control. (See “Playing at Protest,” Spring 2015.) In similar fashion, 1199 continues to promote itself as the radical advocate for society’s underdogs, even as it revels in its status as the most-favored special interest.

In the future, 1199’s power is most likely to be checked from three sources. First would be further closings of redundant hospitals, which would reduce 1199’s ranks and resources. Second, some future governor might apply Cuomo’s general model of labor relations to 1199. Cuomo’s continuing support for 1199 is at odds with his otherwise antagonistic relations with public unions and amicable relations with private unions; 1199 is a government union in all but name. Other governors, such as Chris Christie in New Jersey and Gina Raimondo in Rhode Island, have successfully split private unions and public unions.

Finally, the union could find itself weakened by internal factionalism. Thus far, 1199 has been able to rely on the loyalty of its members, but the history of organized labor suggests that rapid growth and ideological mission creep will eventually create challenges to current union leadership. Traces of factionalism may be seen both in 1199’s past history and, more recently, in the Working Families Party’s decision to endorse Governor Cuomo in 2014, which met with intense opposition from many of its members.

Such developments would be beneficial to New York, and especially to New York City, where 1199 now seems like an irresistible force for the progressive Left. But progressivism won’t always be ascendant. New York will never be a conservative city, but it has traditionally thrived when some right-leaning force has imbued its inherent liberalism with sanity. “Sanity” is about the last thing New York gets from 1199’s dominance.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism