Clint Eastwood’s new film, American Sniper, is a blisteringly accurate portrayal of the American war in Iraq. Unlike most films in the genre, it sidesteps the politics and focuses on an individual: the late, small-town Texan, Chris Kyle, who joined the Navy SEALs after 9/11 and did four tours of duty in Fallujah, Ramadi, and Baghdad. He is formally recognized as the deadliest sniper in American history, and the film, based on his bestselling memoir, dramatizes the war he felt duty-bound to fight and his emotionally wrenching return home, with post-traumatic stress.

The movie has become a flashpoint for liberal critics. Documentary filmmaker Michael Moore dismissed the film out-of-hand because snipers, he says, are “cowards.” “American Sniper kind of reminds me of the movie that’s showing in the third act of Inglorious Basterds,” comic actor Seth Rogen tweeted, referring to a fake Hitler propaganda film about a Nazi sniper, though he backtracked and said he actually liked the film, that it only reminded him of Nazi propaganda. Writing for the Guardian, Lindy West is fair to Eastwood and the film but cruel to its subject. Kyle, she says, was “a hate-filled killer” and “a racist who took pleasure in dehumanizing and killing brown people.”

The Navy confirms that Kyle shot and killed 160 combatants, most of whom indeed had brown skin. While he was alive, he said that he enjoyed his job. In one scene in the movie, Kyle, played by a bulked-up Bradley Cooper, refers to “savages,” and it’s not clear if he means Iraqis in general or just the enemies he’s fighting.

But let’s take a step back and leave the politics aside. All psychologically normal people feel at least some hatred for the enemy in a war zone. This is true whether they’re on the “right” side or the “wrong” side. It’s not humanly possible to like or feel neutral toward people who are trying to kill you. Race hasn’t the faintest thing to do with it. Does anyone seriously believe Kyle would have felt differently if white Russians or Serbs, rather than “brown” Arabs, were shooting at him? How many residents of New York’s Upper West Side had a sympathetic or nuanced view of al-Qaida on September 11, 2001? Some did—inappropriately, in my view—but how many would have been able to keep it up if bombs exploded in New York City every day, year after year?

Kyle had other reasons to hate his enemies, aside from their desire to kill him. In American Sniper, we see him in Fallujah and Ramadi fighting Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s Al Qaeda in Iraq, the bloody precursor to ISIS. His immediate nemesis is “the Butcher,” a fictional character whose favorite weapon is a power drill. The Butcher confronts an Iraqi family who spoke to Americans and says “if you talk to them, you die with them.” He tortures their child to death with his drill.

Kyle kills a kid, too, but in a radically different context. The boy is running toward Americans with a live grenade in his hand. “They’ll fry you if you’re wrong,” his spotter tells him. “They’ll send you to Leavenworth.” He’s right. Kyle would have been fried, at least figuratively, if he shot an innocent, unarmed civilian—regardless of age—with premeditation. In a later scene, he has another child in his sights: the child picks up a rocket-propelled grenade launcher and aims it at an American Humvee. “Drop it,” Kyle says under his breath from far away. He doesn’t want to pull that trigger. He’ll shoot if he must to protect the lives of his fellow Americans, but the kid drops the RPG and Kyle slumps in relief. How different he is from the Butcher, who takes sadistic pleasure in torturing children to death—not even children of the American invaders, but Iraqi children.

So yeah, Kyle thought his enemies were savages and didn’t shy away from saying so. There are better words—I’d go with psychopaths myself—but do we need to get hung up on the semantics? Kyle, along with everyone else who fought over there, should be judged for what he did rather than what he thought or what he said. Had Kyle chosen to murder innocent women and children with his rifle, then we could call him a hate-filled killer with justification. But as far as we know, everyone he shot was a combatant.

We do see actual hate-filled killers in this film, and none of them are Americans. The man who shot them did everybody a favor, and that can’t be undone by his vocabulary. What would you think of a man who kills a kid with a power drill right in front of you? Would you moderate your language so that no one at a Manhattan dinner party would gasp? Maybe you would, but Kyle wasn’t at a Manhattan dinner party.

No experience produces as much anxiety as going to war, and anxiety changes the brain chemistry—sometimes temporarily, other times indefinitely. When the sympathetic nervous system kicks in, it strips away our ability to think in shades of gray. It’s a survival mechanism that evolved to keep us alive; it’s older and more primitive than human consciousness itself. Complex and slow higher-brain reasoning inhibits the fight-or-flight response necessary in times of imminent danger, so the brain is hard-wired to short-circuit around it.

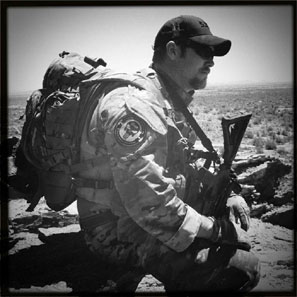

As a journalist in various combat zones, sometimes embedded with the U.S. military in Iraq and other times working solo, I’ve spent time in that mindset. It’s not pleasant and it’s not pretty, but there’s nothing immoral about it. Nearly everyone is susceptible to it. Don’t believe me? Try spending a few months being hunted by ISIS in Syria and watch what it does to your mind. A left-liberal friend of mine in the media business who spent years in the Middle East put it to me this way over beers in Beirut: “I get a lot less liberal when people are trying to kill me.”

I managed to pull myself out of that mental state fairly easily, partly because I experienced no personal trauma and partly because I never spent more than one month at a time in a war zone. But Kyle spent years in that state, and it persisted after he left Iraq and returned home with at least some of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. After his final tour, we see him go straight to a bar and order a beer. His wife calls him and is shocked to discover that he’s back in San Diego rather than still overseas. When she asks why he didn’t come home, he says, “I guess I just needed a minute,” and breaks down in tears. Later we see him in his living room staring at a dead television set while horrific sounds of war explode in his head. Kyle absorbed an extraordinary amount of mental and emotional trauma, stress, and anxiety. This makes him a coward? A psychopath? A hate-filled killer? A Nazi? Seriously?

Here’s a medical fact: psychopaths don’t suffer from post-traumatic stress or any other kind of anxiety disorder. And cowards don’t volunteer for four tours of duty in war-torn Iraq. I live in a coastal city in a blue state, like most of the critics of American Sniper. I was raised with the anti-military prejudice common in my community, despite having a military veteran and Republican for a father. (He served in the army during the Vietnam War, on the Korean DMZ, and to this day has a hard time saying anything positive about the military.)

Spending months with the U.S. military in Fallujah, Ramadi, and Baghdad—the cities Chris Kyle fought in—shattered every stereotype about soldiers and war I had in my head. Michael Moore, Seth Rogen, and Bill Maher likely wouldn’t change their views of war and foreign policy had they done what I did, but they almost certainly would moderate their view of the men and women who fought on our side, if for no other reason than that the words they use to describe men like Chris Kyle apply tenfold to the killers Chris Kyle brought down with his rifle. The people complaining about this film are those who most need to see it, even if watching American Sniper can’t compare with time in the field with the army and the Marine Corps.

I lost track of how many soldiers and Marines told me of their frustration with an American media that so often describes them as either nuts or victims. If we don’t want to lionize them as heroes—Eastwood doesn’t, and Kyle himself is portrayed as uncomfortable with that kind of praise—we should at least understand and respect what they’ve gone through and save our rhetorical ammunition for the other side’s head-choppers and car-bombers.