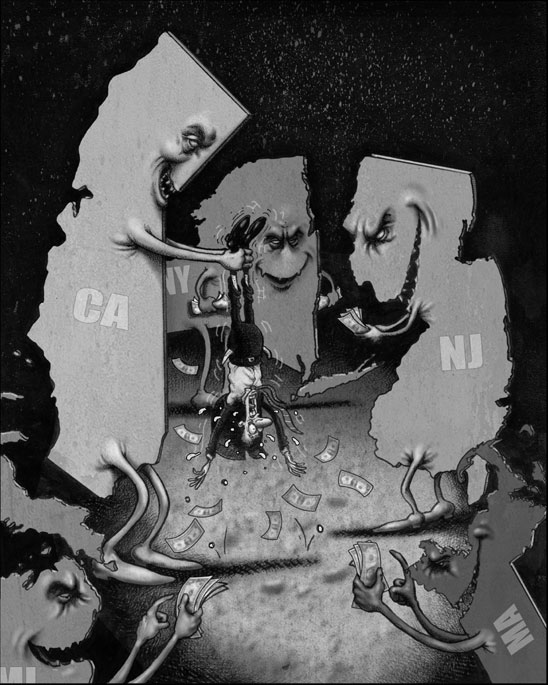

Revenue-hunting states have lately gone beyond raising their own taxes; now they’re trying to shake down firms and workers in other states. Stretching the limits of the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause to the breaking point, local revenue agents have seized out-of-state trucks simply passing through their jurisdiction, refusing to release them until the firms that dispatched them fork over corporate income taxes. Finance departments have slapped out-of-state businesses with bills for thousands of dollars in corporate back taxes, based on little more than a single worker visiting the state sometime during the year. And tax agents have targeted employees who work remotely for in-state firms, claiming that they owe personal income taxes, even when they’ve never stepped foot in the taxing state.

Technological change has unleashed some of this unprecedented aggression. In a world where businesses can offer products to customers thousands of miles away, or sell sophisticated services, such as cloud computing, that seem to originate from nowhere, states that once levied business taxes only on physically present firms have been coming up with far broader definitions for what, and who, is taxable. At best, the states have inconsistently defined what falls under their tax jurisdiction; at worst, they’ve used the transforming technological landscape as an excuse to grab revenues from surprised (and outraged) new sources.

In a 2011 CFO magazine survey, finance officers at large companies judged five states—California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Michigan—as particularly assertive in going after out-of-state revenues. “Given New York’s onerous tax regulations, we are seriously going to consider whether we allow employees to travel to or participate in events in that state,” the CEO of one out-of-state firm told Chief Executive recently. “We can’t afford for N.Y. to become a tax nexus for us just because our employees participate in a conference in N.Y.”

The Supreme Court has invited Congress to clean up this mess, and a handful of bills are circulating in Washington that offer clearer standards on what constitutes “tax nexus”—the state authority to tax a firm or an individual located elsewhere. Yet for years, Congress has put off passing any remedy, causing confusion, bitterness, and sometimes outright panic within the business community. As one corporate-finance officer put it to CFO recently: “The states are in a pure ‘money grab’ mode and don’t care about policy, the law, or fairness.”

Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the Constitution—the Commerce Clause—gives Congress the power to regulate interstate trade. The Supreme Court has always interpreted the clause as limiting a state’s ability to tax the businesses of other states. Generally, the Court required that an out-of-state business had to establish some physical presence in a second state—opening a branch office, say, staffed by several paid employees—before that state could impose a business tax on the firm. Even then, the Court has ruled, the state could only tax a portion of the business’s income, commensurate with its activity there, not its entire profits. Congress has occasionally passed laws that clarify the scope of interstate taxation. A good example was the 1959 Interstate Income Act, which banned states from applying corporate or other business-activity taxes to a firm if its only activity there was to solicit orders.

As business practices have mutated, the Supreme Court has refined its definition of interstate taxation—but not enough to keep up with the myriad new ways that firms operate. In 1992, for instance, the Court ruled that North Dakota could not require a Delaware-based catalog retailer, the Quill Corporation, to collect sales or use taxes on goods ordered by North Dakotans from the firm and shipped into the state. Because Quill had no operations in North Dakota, the Court reasoned, the state violated the Commerce Clause by trying to tax the firm’s transactions. The Court added, however, that Congress could enact legislation defining how states could legitimately tax these kind of exchanges going forward. After the decision, and especially as Internet retailing took off, states steadily lobbied for such a federal law. The U.S. Senate eventually passed one, known as the Marketplace Fairness Act, last May, but it has hit a wall in the House of Representatives because of opposition from states that don’t levy sales taxes and from online and catalog-industry groups, which object to the new burden that their firms would face of owing taxes in multiple jurisdictions.

In the Quill case, the Supreme Court kept states from imposing sales taxes on out-of-state firms, but it said nothing about levying corporate income taxes on them. The decision left an opening for state courts and taxing authorities to start stretching the limits of income or gross-receipts taxes so that they applied to firms with minimal connections to a state. The year after the Quill decision, to take an early example, the South Carolina Supreme Court ruled that Geoffrey, a company created by Toys“R”Us to manage the chain’s various trademark businesses, owed corporate taxes to the state—even though Geoffrey had no presence in South Carolina other than to license trademarks to stores operating there. Since then, state legislatures have begun to craft laws that extend tax nexus to out-of-state firms on the flimsiest of pretexts, from soliciting business in the state to having a brief physical presence there.

Until recently, one of the most aggressive—and, to businesses, infuriating—assertions of tax nexus took place in New Jersey. According to congressional testimony by owners of trucking companies and the American Trucking Associations, beginning around 2000, revenue agents from New Jersey’s department of taxation began descending on truck stops, weigh stations, and loading docks and waylaying trucks, demanding that the owners pay at least Jersey’s $1,100 minimum corporate-franchise tax before letting the drivers proceed. Many of the vehicles—about 40,000 have been stopped—worked for companies with zero connection to New Jersey, other than making a pickup or delivery there. New Jersey was, in essence, charging a $1,100 entry fee into the state.

Hope Trucking, a Florida-based freight company with annual sales of just $250,000, was one victim. In 2005, it sent a driver from Baltimore to New Jersey to pick up some empty barrels. As Hope vice president Ivan Petric put it, the firm’s truck got “ambushed” at a weigh station by a New Jersey revenue agent, who charged the firm with failing to comply with the state’s tax law and informed the driver that “New Jersey had no obligation to provide any notice or legal documentation regarding our noncompliance.” The state demanded $2,200 for two years in back taxes, refusing to let the truck go until Hope had wired the money, despite company officials’ pleas that their firm had no ties to Jersey that would incur the taxation.

In July 2007, in another glaring abuse, the owner of a Hartsville, South Carolina, boating company that had sold some boats to independent New Jersey dealers got a call from a driver saying that revenue agents had seized his truck and were demanding back corporate taxes and penalty assessments of $46,200. The company, Stingray Boats, had to wire the funds to get its truck released. Stingray controller Barry Godwin later testified to Congress: “The manner in which the State of New Jersey acted is commonly defined as extortion. Fortunately, I have never been the victim of crime in my life. But, that day in July, I believe I was strong-armed by a state of the United States of America.”

Robert Pitcher, vice president of government relations for the American Trucking Associations, notes that New Jersey’s aggressive tax posture has eased since the 2009 election of Governor Chris Christie, who has vowed to improve the state’s business climate. But Pitcher believes that, without congressional action, the state could resume its accosting of trucks at any time.

New Jersey’s shakedown tactics have spread. California, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Nebraska, and Virginia have been among the states named in congressional testimony for trying to levy corporate taxes on firms whose only substantial connection is a visiting truck. In one typical case, when a small Milwaukee transportation firm, LTL Trucking, answered a Nebraska tax questionnaire by acknowledging that its trucks had driven through the state in recent years, it received a back-tax bill of $1,321, despite having no inventory, customers, or sales there.

Manufacturers delivering products to customers in locations where the firms don’t otherwise operate have found themselves similarly dunned. Monterey Boats, a company based in Williston, Florida, does only about 2 percent of its sales in Michigan, but this didn’t keep it from getting slammed with a $376,000 bill for Michigan’s gross-receipt tax in 2010. In this instance, too, the firm had no ongoing physical presence in the taxing state. Some 20 states now claim the right to tax the income of an out-of-state business that merely ships products to customers in their state. “What’s particularly challenging—if not chaotic—is that states are imposing these business activity taxes inconsistently,” Monterey’s chief financial officer, Mark Ducharme, wrote in a 2012 opinion piece in the Tampa Bay Times. “Some states reach across their borders and some don’t. Some businesses are targeted, others are not.” The tax grabs have become so outrageous that some states have threatened to retaliate against businesses in the tax-greedy states. Several years ago, Colorado’s legislature issued a resolution calling the state’s tax department to beef up enforcement against trucking firms from states that “unreasonably” go after Colorado businesses.

The Monterey case shows that states aren’t just extending their geographical tax reach; they’re also stretching the limits of how much of an out-of-state company’s business they can tax. Though the Supreme Court has ruled that taxes can be levied only on that portion of an out-of-state business’s income corresponding to its in-state activities, some firms have had to pay much bigger bills, due to creative taxation. Consider the plight of ProHelp Systems, a small, home-based software firm that was located in Seneca, South Carolina. In 1997, the company made a single transaction in New Jersey, selling a license for its software to a company in the state for $675. The state then socked the company for $600 in minimum corporate taxes and business-registration fees—and, worse, said that it would have to pay that sum for every year that the license remained in effect. According to congressional testimony by ProHelp’s owner, Carey Horne, New Jersey tax authorities said that the only way his firm could avoid the tax would be to stop accepting all orders in the state, have zero income derived from it, end all existing licenses to the state’s customers, and have them remove all ProHelp software from their computers. The company understandably began refusing orders in New Jersey. But some other states began assessing their minimum corporate taxes on ProHelp, requiring the firm to file tax paperwork in each state. Horne calculated that if all 50 states adopted those practices, he’d owe $30,000 a year in business-activity taxes. In 2007, he dissolved the business.

In a universe of countless virtual connections, businesses find themselves exposed to state taxes in ways they might never have anticipated. For example, a survey by Bloomberg BNA, a division of Bloomberg that consults on tax and finance issues, found that 16 states now assess corporate taxes on businesses with websites hosted on independent servers in the state, regardless of whether the business itself is physically present. Similarly, all but six states said that they would tax an out-of-state firm if just one telecommuter worked for it from their territory. Half of those governments said that their corporate income taxes would kick in even if the company had zero sales in the state.

The number of companies paying the telecommuting price is growing. In one case decided by California tax authorities in 2012, the state deemed that a Massachusetts firm, Warwick McKinley, owed California taxes from 2006 through 2008. Warwick had neither offices nor clients in the state, but it still had to pay because a California resident worked remotely for the firm. Having a single employee in California, tax authorities decided, was enough to grant Warwick “substantial and enduring benefits and protections of the state,” meaning that corporate taxes applied. Similarly, a Maryland company, Telebright, which had no history of filing taxes in New Jersey, discovered that it now owed the state corporate taxes after an employee moved there, following her husband, who had been transferred. Rather than lose the valuable worker—she created computer code for the firm—Telebright let her work remotely. A Jersey court ruled that the telecommuter was “no different than a foreign manufacturer employing someone to fabricate parts in New Jersey for a product that will be assembled elsewhere.”

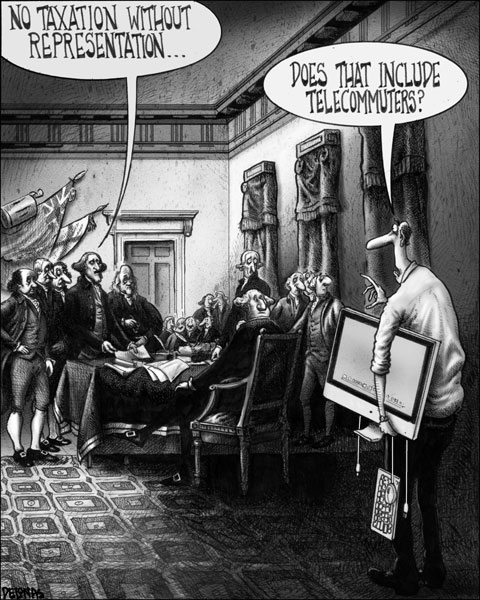

Telecommuting can now be a tax trap for employees, too. New York State now considers those working remotely for New York–based businesses to owe income taxes on all their work, whether they visit the state or not. New York employs a “convenience of the employer” rule to apply these taxes. It holds that telecommuters for New York firms are effectively physically present in the state, wherever they happen to be. A Hawaiian telecommuter to New York, in other words, might wind up paying income taxes in two states—his home and that of his employer.

Edward Zelinsky, a Cardozo School of Law professor, has unsuccessfully challenged New York’s tax in state courts. Zelinsky lives in Connecticut and ventures to New York only on days that he teaches classes at the Manhattan-based institution. Yet New York has for years levied its income tax on all his income, even as he pays Connecticut taxes on income earned when he works at home. This form of double taxation is becoming more common: New York now sends income-tax bills to telecommuters around the nation, and other states have started to do the same. “New York’s projection of its taxing authority throughout the nation has become more blatant and more troublesome,” says Zelinsky. “The temptation to tax nonvoting, nonresidents on days they work at their out-of-state homes has proved politically attractive.”

The irony of such tax policy is that it is sure to discourage telecommuting even as other government policies, including tax incentives, are designed to increase it. As the federal government’s 2010 National Broadband Plan observes, telecommuting can bring more people into the workforce, while reducing road traffic—and hence vehicle emissions—in crowded business districts. Firms can also employ more workers because the cost of office space falls significantly. Yet despite these advantages, many states have upped the pressure on telecommuters. “State taxes that impede the interstate telework dim the promise of broadband,” argues legal scholar Nicole Goluboff in a spring 2013 article in Media Law and Policy.

Some states are clearly more interested in the windfall from an expanding tax reach than in other policy objectives. Experts have put the total take from state taxes on out-of-state firms at half a billion dollars annually in large states such as California, New York, and New Jersey. No wonder that in the environment of the last several years, with states consistently pinched for tax revenues, those extra dollars have some states acting downright hostile to firms from other locales.

The cost of complying with the widening tax nexus of states and of fighting aggressive assessments has now become as big an issue as the additional taxes themselves. The Ohio-based franchisor for Marco’s Pizza stores received a letter from Wisconsin tax authorities requiring the firm to file state corporate income-tax forms because Marco’s licensed its name and format to a single independent store in Wisconsin. The firm’s only other connection to Wisconsin was a single employee who had visited the franchise for a single day. “The ensuing hunt for documents and figuring out how to comply with Wisconsin laws ended up costing us over 40 man hours and thousands of dollars,” Marco’s chief financial officer, Kenneth R. Switzer, wrote in a 2012 opinion piece in The Hill. “Rather than racking up thousands more fighting the tax assessment we paid it.”

Increasingly, finance and tax departments bombard companies around the country with questions about their activities and then send follow-up tax assessments based on the responses. Bobrick Washroom Equipment, a North Hollywood, California, manufacturer, received 15 such questionnaires in 18 months from states. When Texas sent a form, got a response, and then asserted tax nexus over Bobrick, the firm spent $185,000 appealing the decision, but ultimately gave up because of the spiraling legal costs. Bobrick hadn’t exhausted all of its appeals within the state but figured that it was unlikely to win in a Texas court. “Most companies cannot justify the cost of a challenge,” Bobrick president Mark Loucheim told Congress. “As we found in Texas, a company first must exhaust all the state remedies, both administrative and through the state courts, before the company can proceed to federal court in hopes that the U.S. Supreme Court eventually will take the case. Based on our estimates, this process could take multiple years and cost millions of dollars in legal fees.” Even then, the effort might prove fruitless: the Supreme Court has refused since its 1992 Quill decision to take cases concerning tax nexus, reasoning that it has already asked Congress to set new standards in an evolving business landscape.

Along with the extraordinary administrative costs they impose, states that are brazenly expanding their tax nexus violate fundamental principles of taxation, argue critics. “Determination of jurisdiction to tax should be guided by one fundamental principle: a government has the right to impose burdens—economic and administrative—only on businesses that receive meaningful benefits or protections from that government,” maintained the Council on State Taxation, an industry group, in testimony before Congress. Taxed businesses in many of these cases, however, receive no such substantial benefits.

In the same way, argues Zelinsky, when states overreach on taxing nonresidents, they undermine the federalist principles of the U.S. Constitution. “Central to the federalist enterprise is the ability of each state to tax and govern within its own borders. National legislation outlawing New York’s (and other states’) taxation of out-of-state telecommuters would enhance federalist values by protecting the states in which nonresident telecommuters live and work.”

But as Congress dithers, the problem is rapidly worsening. To preserve their right to tax out-of-state businesses, states are even withdrawing from a compact they formed in 1967, which determined tax nexus by assessing the amount of sales, property, and payroll that a firm had in a state. Firms with sales in a state but no property or employees were not subject to corporate taxes in the arrangement. As they have grasped for revenues, more than two-thirds of states have now abandoned the compact’s terms and enacted their own looser rules.

Advocates for tax simplification have introduced a series of bills in Congress that would clear up the tax-nexus confusion. The Business Activity Tax Simplification Act of 2013 would require that a firm have a minimal physical presence in a state before tax authorities could assess corporate income or other business taxes on it. The legislation also would require that companies operate in a state for a minimum of 15 days before they could be considered physically present; no firm could be assessed corporate taxes merely if an employee visited a state. Businesses must also own or lease some property in the state for taxes to apply, the act proposes, and it specifically states that just owning or licensing software doesn’t constitute such property. Introduced by Wisconsin Republican representative Jim Sensenbrenner and cosponsored by two Democrats and five Republicans, the legislation “aims to clear up what the [Supreme] Court left vague and ripe for misinterpretation,” Sensenbrenner said when introducing it. “Some states have misconstrued their authority to levy business activity taxes, which has resulted in uncertainty for small businesses and state governments alike. [This legislation] resolves the existing ambiguity by establishing a clear and concise rule for when a sufficient connection exists to justify taxation.”

Two other pieces of legislation previously introduced in Congress address telecommuting and taxation. The Multi-State Worker Act (previously known as the Telecommuter Tax Fairness Act) prevents a state from taxing the income of a nonresident when he’s not located in-state. States like New York could no longer use the so-called “convenience of the employer” rule to treat telecommuters as if they were physically present in the state for tax purposes. The Mobile Workforce Act, like the 2013 simplification law, bans states from taxing the income of an out-of-state worker who merely visited the state briefly, and it mandates that employees would have to spend a total of 30 days or more a year in a state before taxes would apply on income earned there.

Businesses have made little headway in advancing this legislation in Congress, in part because states have kept the focus on the battle over taxation of Internet sales. But the Marketplace Fairness Act is just one part of the modern puzzle over what constitutes tax nexus. Congress should be considering the range of taxes, including those on corporate and personal income, as it contemplates the thorny issue of who and what states can tax these days.