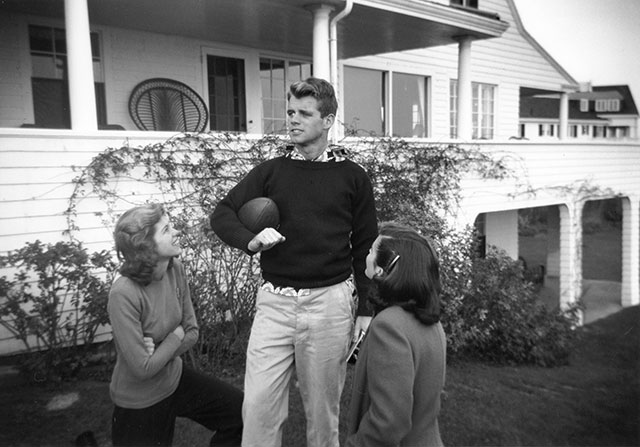

Bobby Kennedy and the other men wore button-down shirts with frayed collars, crew-neck sweaters gone at the elbows, and khaki pants and dirty white sneakers. Bobby’s older brother Jack showed up once or twice, leaning on crutches, watching from the sidelines. There were small children on the sidelines, too, Kennedys and others, and a dog or two. Bobby’s wife, Ethel, played sometimes. One Saturday, when she was about six months pregnant, she dropped a pass. Bobby bawled her out. He yelled at her and the veins stood out on his forehead. I laughed. Bobby glared at me.

It is 50 years since Robert Kennedy’s assassination. It is even longer—65 years—since, as a boy, I first encountered him on the field of a playground in Georgetown.

My family lived on N Street between 33rd and 34th. I hung out at Georgetown playground, a few blocks up the hill, on 34th, between Volta Place and Q Street. Bobby and Ethel Kennedy and the first of their many children lived nearby, on S Street.

It was Dwight Eisenhower’s first year in the White House. Bobby had been working as assistant counsel for Joe McCarthy’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (I knew nothing about that). On Saturday mornings, he and his friends and family would play touch football on the playground’s field. If Bobby and friends were short of players, they would invite me into the game.

The game was Kennedy football, which meant that the men played rough, hitting hard, playing not so much touch as semi-tackle. The hard hits seemed a little over the top—contaminated by a sort of bully’s nostalgia for his days on the varsity, or something along those lines. A hard block might send one of the men sprawling onto the field, which was scruffy-bare, embedded with gravel that tore the crew-neck sweaters. The men jostled and slammed and banged one another. Mostly, they spared the kids (including me) and the two or three women who played.

In Kennedy touch, there was no line of scrimmage after the ball was hiked—you could pass or lateral anywhere on the field. That gave the game an air of merry improvisation and a curiously irritating spirit of entitlement (you could do anything—go anywhere, pay any price). It was like playing high-low poker, seven-card stud, with half the cards declared wild. It seemed careless, and a little like cheating.

In later years, I wondered if that antinomian football may have been a sign (naive, unwitting) of something darker. Was it connected (psychologically, metaphorically) to a mentality that would prevail in the CIA and Jack Kennedy’s New Frontier later on, and might it—in hidden passages of the ruling-class psyche of the time (that mind, let us say, when it was engaged in discussing foreign policy after three martinis at lunch at the Metropolitan Club, or after twice that many drinks at a potluck Sunday night dinner at Joe Alsop’s house in Georgetown)—have led to certain bad things that followed?

If the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, maybe the Bay of Pigs was lost, as it were, on the playing fields of Georgetown.

One Saturday morning, I played on the team captained by Byron (Whizzer) White. I knew nothing of White’s background. After the game, one of the other kids told me that he had once played professional football. I believed it.

White had been an All-America halfback at the University of Colorado, before he went on to play (All-Pro) for the Pittsburgh Pirates (who became the Steelers) and the Detroit Lions. He studied at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, graduated from Yale Law, and served as a World War II naval intelligence officer. In the New Frontier, he would be deputy attorney general under Bobby and, in 1962, would join the Supreme Court, where he served as associate justice for 31 years.

Whizzer White was our quarterback. Bobby Kennedy called plays for the other team. In the huddle, White told me to go deep, straight down the right sideline. I set out from the line of scrimmage, with Bobby in pursuit. When I was far downfield, I stretched out my hands and looked over my right shoulder—and the ball was there. Whizzer White had sailed a perfect arcing spiral to me: a ball that floated down to me as if in slow motion, as big and soft as the moon. I gathered it in and sped over the goal. Bobby was a stride behind me and looked furiously frustrated, like the devil thwarted.

I think of that catch now and then. As in a dream, I seem to be flying, or almost flying. Whizzer White’s pass is the ideal of what a pass might be if God himself had thrown it.

The Greek philosopher Euhemerus (330–260 BC) had a theory that the gods began as ordinary human beings. As mortals, they performed notable deeds. The stories of those deeds came to be repeated, and embellished, as good stories usually are. In many retellings, they would be improved and distorted and distilled, until the mortals who had done the deeds would acquire refulgent new lives, as myths. They would not be mortals anymore. They would escape from the gravitational pull of time. They would turn into gods.

In the transformation—alchemy by narrative, by exaggeration, by idealization, by lies (if you insist)—mere flesh and blood and bone would perish, so that it might return, perfected, and take a place in the moral drama of the universe.

Bobby Kennedy, I think, is a case study of the Euhemeristic process at work in the modern American framework of religion, politics, celebrity, all mingled—a vivid man in passage from the intense, profane reality of his time to the realms of sacred memory.

“The entire Kennedy family phenomenon is impressive as a prototype of publicity leading on to myth.”

Of course, the entire Kennedy family phenomenon is impressive as a prototype of publicity leading on to myth. The Euhemerus process in modern times is much accelerated and intensified by globalized electronic information and social networks. As time passes, the business of fame—carried on in the complicated, unstable metaphysics of the global imagination—becomes increasingly savage and strange. It’s not impossible to become a god these days, but it’s nearly impossible to remain one. The Euhemerus effect now runs powerfully in the negative direction, down from Olympus: incipient gods are disgraced and discarded overnight. The web is Moloch.

But the Kennedys, despite scandals, have survived, as if they had been grandfathered into the myth-systems. The grandfather was Henry Luce. Just before World War II, Life began glorifying the photogenic family. Ambassador Joe Kennedy went to London, and Rose and the children came after him, stepping off the boat as bright as newly minted dimes. Less than a century after the potato famine, America’s immigrant Irish returned across the water, transformed by America, civilized by Harvard, their money and their white teeth gleaming. The Kennedys have lived ever since in a Euhemeristic borderland in the American imagination.

But they have kept their mythic prestige, it must be said, only at the terrible cost of the double martyrdom that, on the other hand, saved John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy from the hazards of ongoing history—which would have been hard on their historical reputations. Their secrets would almost surely have come out, the scandals would have multiplied, and their enemies would have pounced. It’s possible to imagine John Kennedy’s presidency being destroyed in his second term by a scandal of Watergate proportions, centered on one or more of his high-risk sexual liaisons (with the Mafia boss Sam Giancana’s girlfriend Judith Exner, for example, or with Ellen Rometsch, an East German woman who was hustled out of the country as a possible spy), or else involving lies about his medical condition. J. Edgar Hoover had a thick dossier.

But both brothers were called to martyrdom. Nil nisi bonum. Their deaths carried them into safer realms of wistful speculation, into the cirrocumulus clouds of What Might Have Been, the snow globe of Camelot.

In a way, Bobby’s is the family’s completest story, with the clearest moral contours. His tale had a beginning, a middle, and an end, and was most like a parable, in that it traced a true change in his heart that, for all his contradictions, seemed profound and exemplary. His story was, in its way, the most moving of them all. It seems to me that he (more than John) left an authentic ache in the American heart.

The thought of him, just now, sent me back to the Walt Whitman lines that my mother read to me when I was five—much too young to understand:

There was a child went forth every day,And the first object he looked upon and received with wonder or pity or love or dread, that object he became,And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part of the day or for many years or stretching cycles of years.

Bobby Kennedy was Whitman’s child that went forth; anyway, that is the version of him that has been perfected in American memory in the years since Sirhan Sirhan shot him. In popular memory (a sentimental dream of archetypes), he enacted a theology of American experience—innocence on the path of learning and becoming. The child would prove to be the best man.

In a recent biography, Chris Matthews repeated the wishful thesis—a case filled with ardent subjunctives—that Bobby Kennedy, had he lived and had he won the presidency in 1968 (a very big if), might have reconciled America to itself—that he would have healed the divisions that had been produced by the Vietnam War and by the wounds of race. The lion would lie down with the lamb. The culture would lie down with the counterculture. The violent American differences would be composed. Blue-collar whites would be united with blacks in their faith in a Bobby transcending the usual politics and hatreds (a faith validated, as it were, in the benevolent illogic of grace). Hawk and dove would be reconciled because Bobby, after all, would end the war. The theory depended, above all, on that article of faith.

Could Robert Kennedy have turned America into the Peaceable Kingdom? Or was it inevitable that divisions would deepen over the years as the implications of the 1960s reverberated through American society?

Immense changes were at work—in the lives and roles of women, in the relations between the races, and in the ethnic composition of the country, now that the Immigration Act of 1965 had eliminated preferences for European immigrants and opened the doors to millions of new citizens from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. The sixties established the battle lines of the culture wars. Would Bobby have managed those fundamental conflicts—the great issues of moral and cultural transition—better than did those who, in fact, inherited the power (Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan)? Perhaps he would have. I like to imagine he would have made an enormous difference, had he been elected president. But to think so is to test to the limits Carlyle’s Great Man theory. It’s my belief, in any case, that Bobby could not have gotten the Democratic nomination in 1968, not with Lyndon Johnson (who loathed and despised him) controlling so many of the convention delegates and determined to bestow them upon Hubert Humphrey.

The thesis that Bobby might have changed everything starts with the unarguable truth that Bobby Kennedy was not Richard Nixon—a distinct advantage. (Nixon, on the other hand, harbored a grievance that he was not born a rich and glamorous Kennedy and could not get away with the reckless amorality that was, Nixon believed, the Kennedys’ usual way of doing business. It has often been observed that it was that line of thinking—beat the Kennedys at their own game—that led Nixon into the nefarious ways of Watergate.)

A long time ago, at lunch in the Four Seasons restaurant in New York, I heard a Hollywood producer say: “I wanted Steve McQueen for the part. But he’s dead.” So it was with Bobby. We wanted him for the part—many of us did, anyway. But he was dead.

Chris Matthews, having Irish roots himself, could not help conjuring Bobby as a sort of Irish Rover, the wild boy as hidden aristocrat (the old Hibernian daydream), friend of the people (blacks, Chicanos, the antiwar young), who—before his death, in the great comprehensive crisis of 1968—had come to claim his title as rightful king and “lord of these lands all over,” as the lyrics say—lord protector, white knight, healer, and redeemer of the American miseries. He would somehow deflect history itself—calm the raging sea.

In death, he was a boy fixed forever in the fatal moment he became a man:

The minstrel boy to the war is gone,In the ranks of death you’ll find him;His father’s sword he has girded on,And his wild harp slung behind him.

In history, timing is everything. Jack and Bobby Kennedy were dreamboats who came onstage in the days of the baby boomers’ youth—the 1960s, a time that (like the early Church) was drenched in myth and fervors and martyrs and new faith.

Now, in 2018, the boomers are settling into old age. It was “unforeseen, but not accidental” (as Trotsky used to say) that that generation’s last chapters should reverberate with themes of their youth—bitter, angry divisions, the culture wars worse than ever, with uncompromising hubris and self-righteousness on all sides of every controversy, and each combatant accusing the other of turning the country into a travesty of itself.

Bobby and Jack Kennedy were characters entirely different from each other. Bobby will endure as the truer saint, I suspect, the one more authentically reverenced in an America whose intensely religious imagination and value systems permeate its politics and popular culture, especially (ironically) among those people who think themselves most secular and “enlightened” and content to do without God. G. K. Chesterton called America “a nation with the soul of a church.” The separation of church and state in America is a useful piety, but church and state are not separated in the minds and emotions of the Right or the Left. The constitutional separation is indispensable but, as a practical matter, mostly an illusion. There is too much Euhemerus at work.

Jack Kennedy had charm and a genius for irony and facade; his story was contaminated, or at least complicated, by deception: by the near-fatal illnesses (Addison’s, among others) that he concealed; and by the risky, recreational sex with which he amused himself behind the nation’s (and his wife’s) back.

Bobby, intense, or “ruthless,” as people said, was incapable of irony or facade. He had a purity of energy and heart—and a Jansenist streak. A devout Catholic altar boy from the days of the Latin mass (Introibo ad altare Dei, ad Deum qui laetificat juventutem meam), he nevertheless most closely resembled the Protestant John Bunyan’s Christian in The Pilgrim’s Progress, earnest and single-minded and fierce. (Jack Kennedy, in Bunyan’s scheme, played the less interesting part of Mr. Worldlywiseman.) Bobby’s life, like Christian’s, was a journey—The Education of Robert Francis Kennedy.

There was the famous Bad Bobby (the one who authorized wiretaps on Martin Luther King, Jr., for example). But—after many dangers, toils, and snares, as the hymn says—there came the Good Bobby, the one who stood in the parking lot in Indianapolis and (in a moment of painful grace, of unforgettable moral theater) revealed to his black audience that King had just been killed in Memphis. Indianapolis, unlike many other American cities, did not erupt in riots that night, or in the nights and days that followed. Bobby’s talk to the crowd that night would be remembered, like other moments of his life, as a moment touched by something like grace, by a tragic understanding born of suffering. (Charisma is Greek for “gift of grace.”)

That was the essence of Bobby’s hagiological story line. It harbored aspects of pagan-to-Christian transformation (a repudiation of Machiavelli, of dark, conspiratorial statecraft) and proclaimed a conversion from a sort of Roman ruthlessness (the Bobby of the McCarthy days, and Operation Mongoose) to mercy and love and, in the blood-sacrifice of his death, an imitation of Christ.

The Kennedys were saturated in myth, in what a cynic might call the public relations of myth: mystic publicity. After Jack died, Jackie encouraged Theodore H. White—a master of popular mythmaking, trained by Henry Luce himself—to write of the Kennedy administration as Camelot, the brief shining moment.

In Bobby, the Christian sacrifice became conflated with Greek tragedy, with lines of Aeschylus that Jack evidently taught his younger brother: “He who learns must suffer. Even in our sleep, pain that cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.”

The virtue that grief and suffering taught Bobby—humility—is not to be found anywhere today in American politics.

Bobby got into the 1968 presidential race in March—belatedly and, some said, cravenly—after Eugene McCarthy did well in the New Hampshire primary and proved Lyndon Johnson’s vulnerability to a challenge from the antiwar Left. As soon as Kennedy-for-President bumper stickers were available, I put one on my yellow Volkswagen Beetle. I lived in Manhattan, and when I was not using the car, I parked it in the driveway at my father’s house in Bronxville and left the keys with him.

He worked for Nelson Rockefeller, as speechwriter and press secretary and political advisor. Rockefeller had had some thought of opposing Nixon for the presidency that spring but, unlike Bobby, did not have the courage or the will to plunge in. My father was not a partisan or doctrinaire man—he was a sort of Norman Rockwell sentimentalist about the country, and tended to regard politicians as buffoons, either vicious or endearing (he had, after all, been raised on H. L. Mencken, and he had covered the Roosevelt White House for the Philadelphia Inquirer, admiring FDR as a subtle and effective and hilariously accomplished hambone). In his rendering, politicians were bombastic performers, in the style of W. C. Fields.

Yet my father hated Bobby Kennedy. Why? I never understood his reasons. It seemed personal, and was probably connected to something that happened when my father knew him on the Hill, in the days when Bobby worked for the McCarthy subcommittee. My father never referred to Bobby without adding the words “that little shit.” My father almost never used such language. He was a sweet-natured man, yet he singled out Bobby for uncompromising hatred.

“Bobby’s talk that night would be remembered, like other moments of his life, as a moment touched by something like grace.”

I would leave the Volkswagen in my father’s driveway for several days or a week at a time, and every time I came back to get it, the KENNEDY bumper sticker would be gone. I never said a word to my father about this. Back in Manhattan, I put another KENNEDY sticker on the car. In a little while, I would return the car to Bronxville, and after I had left, my father would quietly remove the new sticker. And I would replace it the next time around.

In the thick of the eventful and appalling spring of 1968, neither of us said anything about our little bumper-sticker routine. We both thought it was funny. We never mentioned it.

I went out to Indiana and chased Bobby’s primary campaign around the state, listening on the radio to the endlessly repeated lyrics of “Mrs. Robinson.” Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio, A nation turns its lonely eyes to you, woo woo woo.

After Bobby was killed, my father gave up referring to him as “that little shit.”

There is one last story about Bobby’s football games.

I was not there on the day that the following incident occurred, but I heard about it later, from boys who were friends of mine. In years to come, the story would be much embellished, and from it, you could extrapolate the Good Bobby or the Bad Bobby, depending on your inclination.

Lawrence O’Brien was there to witness it. A longtime fixture in the court of the Kennedys—he was an accomplished political operator from Springfield, Massachusetts—O’Brien, with his wife, Elva, was visiting the Bobby Kennedys that weekend. Along with Senator John Kennedy and youngest brother, Ted Kennedy, they all went over to Georgetown playground for a game of touch. Jack was on crutches and remained on the sidelines, talking with O’Brien as events unfolded on the field.

Amazingly enough, the story did not get into the newspapers. O’Brien would tell it, 20 years later, in his memoir called No Final Victories. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. would repeat O’Brien’s version in Robert Kennedy and His Times (1978), and all other subsequent biographies, including Larry Tye’s admirable Bobby Kennedy (2016), cited O’Brien as the source.

My version—formed on hearsay from friends—presented, quite distinctly, the Bad Bobby. O’Brien offered his readers, if not the Good Bobby, at least a somewhat Better Bobby.

The left field of the baseball diamond at the Volta Place end of Georgetown playground merged with the football field. On this Saturday, some youths—local high school kids, in my version; Georgetown University graduate students, in O’Brien’s version—were playing baseball, hitting fly balls into left field that landed amid the Kennedy football game.

In O’Brien’s version, Teddy Kennedy got into an argument with one of the baseball players about this, and was about to get into a fistfight with him when Bobby—a much smaller man than his brother, shorter by five or six inches, and considerably lighter—brushed Teddy aside and said that he would do the fighting. O’Brien’s version said the youth was a great big guy. If he was a grad student, he would have been in his early to mid-twenties; O’Brien implied that little Bobby (aged 28 at the time) was a valiant underdog.

O’Brien was there, and I was not. But the way I heard it, Bobby’s opponent was a local teenager. I thought I knew him—a good athlete who played on Western High School teams with my older brother Hugh. This kid, as far as I know, never made it to college, and certainly not to Georgetown. In my version, there was a factor of social class involved in the collision. The local kids resented the Kennedys and their friends.

Georgetown in those days was still imperfectly genteel; starting during the New Deal years, a lot of State Department and (in time) CIA people, along with such fancy journalists as Joseph Alsop and Katharine and Philip Graham and James Reston, had moved in, joining the old money there. But there were still many working-class whites—and blacks.

That morning, Bobby and the youth got into a serious, spectacular fistfight. It lasted for a long time (20 minutes? half an hour?), both boxers throwing hard punches to the face and body, fighting like gladiators, bare-knuckle, all over the field, in front of the Kennedy children and the other Kennedy brothers and Larry O’Brien, who kept telling Jack that they ought to leave because the newspapers might get hold of the story and it would not look good for Bobby or Jack.

In either version of the story, Bobby’s behavior seems bizarre, the violence of it unsettling and unnecessary and immature—inappropriate, to use the prissy word. It seems strange, too, that the bystanders did not intervene, but rather, stood by passively, deferring to Bobby’s fury and (one surmises) to the spirit of Ambassador Joe Kennedy, who may have been the true instigator of the fight, having brought up the boys on the idea that Kennedys never come in second.

The two fought on, until both were exhausted and battered and a little bloody, and unable to continue. Bobby did not come in second, but he did not come in first, either. It was a stalemate, like the war in Korea.

I tell the story because, passing through time, it seems to me an illustration of the Euhemeristic process. O’Brien’s version is probably more reliable than mine, but only a bit; I suspect that he skewed the details in Bobby’s favor—making the youthful opponent older and heavier and stronger than he really was. I doubt that the other fighter was a Georgetown University graduate student. Such students would more likely have played baseball on the university’s athletic fields some blocks away, and not at Georgetown playground. Further, the kids who told me the story knew all the Western High School athletes (as I did), and I think that they knew the guy who fought Bobby.

It’s an odd story, somehow revelatory. Plutarch thought that details like this may tell you what you need to know about a great public figure (more than you may learn from the great historical events).

Adlai Stevenson would never have gotten into a fistfight like that (and Bobby and Jack believed, accurately, that that was Adlai’s problem). Even if Jack—old Mucker from Choate—had been in perfect health, it is hard to imagine him getting into such an undignified brawl. What would Dick Nixon have done?

But Bobby’s adrenal glands were fierce, and he had about him a heedless (and charismatic) physicality that made him dangerous and sometimes stupid in the clutches. It was a belligerent instinct that, in the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, prompted him—at first, before he had time to understand the gravity and dimensions of the problem—to side with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and others who favored an immediate attack on Fidel Castro’s missile bases.

But that crisis—so terrifying, so dangerous—would (in the evolution of the Bobby legend) come to dramatize his conversion from the nuke-’em mind-set of Curtis LeMay to the subtler wisdom that (with a potent admixture of luck or Providence, and the unexpected forbearance of Nikita Khrushchev) would lead President Kennedy to respond to Khrushchev’s first letter and ignore the second, and (with a secret side deal calling for the removal of American missiles from Turkey) thus resolve the crisis without bringing on the nuclear winter. Euhemeristic history is complex and contradictory, however, and after the Russians had steamed away, taking their missiles with them, Bobby would go on obsessing about Fidel Castro and pushing the CIA to do something about him.

In the story of Saint Bobby, with its intense lights and darks, there would linger (in shadows) the question of whether the things that Bobby did, in his relentless plotting against Castro, led to a counterplot that came to fruition in Dallas on November 22, 1963.

Top Photo: Philadelphia, 1968: Robert Kennedy is thronged at a campaign appearance. (AP PHOTO)