John Wayne: The Life and Legend, by Scott Eyman (Simon & Schuster, 672 pp., $32.50)

Back in 1969, a staffer from the Hollywood Reporter spoke to a film star about the new “oaters,” among them The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and The Wild Bunch. “Westerns are different today,” he observed.

“Not mine,” replied John Wayne.

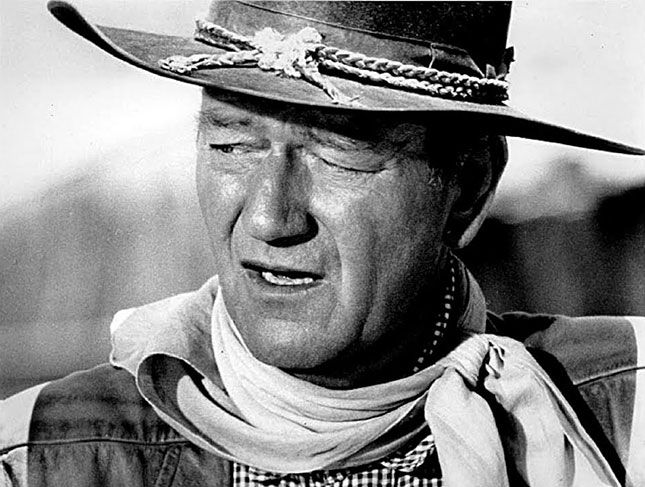

That was at once his strongest asset and his greatest liability. The Duke, as he was known in Celluloid City, was a consistent performer, a box-office draw, a wide-screen personality in more than 200 films. Yet in almost all of them, John Wayne played “John Wayne,” the drawling galoot with the distinctive sloping walk. He was slow to anger, but you’d better duck behind the bar when he did get mad, because he had a gun and a word that never failed. That’s what audiences wanted, and that’s what he gave them, over and over again, working with the most celebrated directors of the cinematic Golden Age, among them William Wellman, Henry Hathaway and, most prominently, John Ford.

If versatility was not Wayne’s long duster, he remained a Hollywood icon for over three decades and his career deserves a serious appraisal. Scott Eyman supplies it in 658 pages of cinematic, personal, and financial detail. Much of it is revelatory: Marion Robert Morrison was born in Winterset, Iowa. His father was an unsuccessful druggist, his mother something of a shrew. The family journeyed west to Glendale, and from then on Big Duke (his dog was called Little Duke and the sobriquet stuck) regarded himself as a native Californian.

Duke was never the lunkhead caricatured by impressionists like Rich Little and Robin Williams. He could recite long passages from Hamlet; he was a knowledgeable art appreciator (and later collector), an avid chess player, and something of a wit. Looking in the rearview mirror, the beefy actor with the graying toupée recalled, “I’ve had the most appealing of lives. I’ve been lucky enough to portray man against the elements at the same time as there was always someone there to bring me the orange juice.” The climb to the top was not as easy as it sounded. Wayne served a lengthy apprenticeship in low-budget Westerns, contemporary melodramas, and later on, some ludicrous costume dramas. In The Conqueror, for example, he played Genghis Khan, informing Tatar woman Susan Hayward, “Yer beoodiful in yer wrath.”

His real breakthrough came as the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach. From there, he went on to play such stalwarts as Captain Nathan Brittles in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the marksman Tom Doniphon in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, U.S. Marshall Rooster Cogburn in True Grit and, most memorably, the aging and embittered cowpoke Ethan Edwards in The Searchers.

Arguably John Ford’s greatest film, and certainly the Duke’s finest two hours, The Searchers remains, half a century later, the epic of the Old West at sunset. Wayne delivers a larger-than-life performance as a bewildered nineteenth-century figure brimming with rage at the country’s imminent social and political changes. But this is not enough for Eyman. “If [Marlon] Brando’s triumphs were the external life of Stanley Kowalski and the internal lives of Terry Malloy and Vito Corleone,” he burbles, “then Wayne combines all of these into Ethan Edwards.” This is not biography but cheerleading. Wayne, unlike Brando, had little interest in realism. Neither did Ford. In collaboration, they made their own rules and created their own exaggerated, romantic persona for the actor. And Wayne, again unlike Brando, has left no disciples and has had little influence on generations of succeeding performers. There’s nothing wrong with that; neither did Cary Grant, Humphrey Bogart, or Fred Astaire. But Eyman is rarely content to present his subject full-length, warts and all. Indeed, he is at pains to airbrush those warts whenever they appear.

Item: Wayne never served in the armed forces during World War II, unlike Clark Gable, James Stewart, Tyrone Power, and many other colleagues. He kept getting deferments until he was 38, and therefore overage. Duke had powerful military connections and could have gotten into uniform, but his reputation as a macho leading man took precedence. “I would have had to go in as a private,” he grumbled. “I took a dim view of that.” Eyman hastily adds that as the war was winding down, Duke went on a U.S.O. tour where, in New Guinea, the troupe saw some action. A battalion adjutant was awed. The superstar “became one of us. He was just like everyone else. He showed us that he really was a down-to-earth guy . . . He didn’t ask for any protection.”

Item: Duke never made a secret of his conservative politics, but occasionally they lurched past Barry Goldwater and onto some dubious turf. He became a member of the far-right John Birch Society, a group whose leadership opposed the civil rights movement and regarded Dwight Eisenhower as treasonous. Wayne, Eyman assures us, “ultimately became uneasy about the Birch Society.” The reason: “Its campaign against fluoridation.”

In the end, Duke was both liberated and imprisoned by his carefully nurtured image. As the movie critic of Time, I wrote a cover story about True Grit that helped Wayne get his one and only Oscar. I asked him then how he wanted to be remembered. He thought about it for a minute. “Well, the Mexicans have a phrase, Feu, fuerte y formal, which means: he was ugly, was strong and had dignity.” Duke got his wish. But first he had to prove himself to himself one more time, and the occasion was tragic. A few years before his death in 1979, the six-pack-a-day smoker was diagnosed with cancer. According to Eyman, “It was one of those moments when the hearing suddenly disappears and there’s a sudden coldness in your fingers.”

“I sat there,” the actor remembered, “trying to be John Wayne.”