In March 1969, 19 months after riots had devastated Newark, Philip Roth took to the New York Times with a plea to save the city’s library. In a budget-cutting move, the Newark City Council had proposed slashing funding for the library’s main branch and the adjoining Newark Museum, two notable landmarks constructed during more prosperous times in the early twentieth century. “When I was growing up in Newark,” wrote Roth, “we assumed that books in the public library belonged to the public. Since my family did not own many books, or have the money for a child to buy them, it was good to know that solely by virtue of my municipal citizenship I had access to any book I wanted from that grandly austere building downtown on Washington Street.” Soon after Roth’s appeal, city council members found the money to keep the library and museum operating, most likely because they never really intended to shutter two of the city’s signature institutions. The threat was likely a way to dramatize Newark’s accelerating decline.

Nearly five decades later, Newark is described as a failed city, “a classic example of urban disaster,” “the worst American city,” and “America’s most violent city.” One of Roth’s own characters, Swede Levov, from his 1997 novel American Pastoral, calls Newark a place that once “manufactured everything” but turned into “the car theft capital of the world.” Still, Roth, who left Newark in 1951 for college and a writing career that includes a novel titled Letting Go, has been unable to let go of the city. Last October, he announced that he was bequeathing his collection of 4,000 books to the Newark Library—recognition of the role that Newark played not only in his life but also in his work.

The city, as well as characters from it, has figured in more than half of Roth’s 27 published novels, in his two autobiographies, and in numerous essays and interviews. Roth’s Newark stretches from his first book-length work, 1959’s Goodbye Columbus, with its protagonist working at the Newark Library, to his most recent (and final, he says) book, Nemesis, a striking 2010 novel about a polio epidemic’s impact on his Weequahic neighborhood during the 1940s. There may be no more expansive portrait of an American city in literature by a single author. And because Roth grew up during the mid-twentieth century, his Newark tales also offer a chronicle of something that has largely vanished from America: a flourishing blue-collar urban environment, where immigrants pursue the American dream for themselves and, especially, for their children. The literary critic Leslie Fiedler, who also grew up in Newark, described the city as an ordinary place even in its best years, not magical like Paris or New York and “not even a joke like Peoria.” Yet in Roth’s hands, the city’s working-class neighborhoods become unforgettable landmarks. “Sitting there in the park, I felt a deep knowledge of Newark,” librarian Neil Klugman observes in Goodbye Columbus, “an attachment so rooted that it could not but branch out into affection.” Unless you grew up in Newark, as I did, it might be impossible to imagine that city. It still exists, however, in Roth’s words.

Seeking freedom from meddling colonial officials, a small group of Puritans from the area around Milford, Connecticut, traveled to the banks of the Passaic River in New Jersey and founded Newark in 1666. As the American colonies grew, so did Newark, situated strategically between two vital trade centers, New York and Philadelphia. After the American Revolution, as the young country struggled to diversify its economy so that it no longer had to rely on England for crucial goods, Newark became more than a way station between bigger cities; it emerged as a major manufacturing center, inspired in part by Alexander Hamilton’s ambitious project, just a few miles up the Passaic, at Paterson, where he and a handful of investors forged America’s first industrial center.

The talent of a few local tanners and shoemakers made Newark a magnet for entrepreneurs in leather-related goods, among them a young go-getter, Seth Boyden, who arrived in 1813 and invented patent leather. Later, Thomas Edison kicked off his astonishing career in the city, where he moved in 1871 and set up a laboratory and manufacturing facility. As Newark prospered, its population burgeoned: from a mere 4,500 in 1800 to 72,000 at the start of the Civil War, and from nearly 247,000 by the turn of the twentieth century to 442,000 in 1930. Many of Newark’s new residents were foreign workers, helping to build the city and staff its factories—including Irish laborers working on the Morris Canal during the 1820s, then Germans in the 1840s, and later Poles, Slavs, Greeks, and Italians. By the twentieth century, two-thirds of Newark’s population was foreign-born; census takers could identify more than 30 city neighborhoods with a predominant ethnic or racial group.

Newark’s first established Jewish community comprised mid-nineteenth-century German immigrants. The Jewish neighborhoods that Roth knew in the 1930s and 1940s, though, were peopled by the great wave of Eastern European immigrants who arrived from the early 1880s through the mid-1920s—some 2 million Jews, largely from Russia and Galicia. Perhaps as many as 50,000 of those sojourners made their way to Newark. They lived initially in tenements in and around Prince Street, in the city’s old Third Ward. Among the residents: Roth’s paternal grandfather, who worked in the tanneries to put food on the table for seven kids, including Roth’s father, Herman. Then, as the immigrants’ children assimilated, they gradually moved west, forming a lower-middle-class ethnic stronghold at Newark’s edge—some 58 streets of apartment buildings, small houses, and bustling shopping thoroughfares known as Weequahic, an Indian phrase meaning “head of the cove.”

To the contemporary social scientist, indoctrinated in the virtues of diversity, a city of thick, somewhat insular, ethnic neighborhoods like Weequahic must seem like the antithesis of true community. But to the immigrants of Newark and their descendants, those neighborhoods offered a safe harbor, a place where they could grow up surrounded by familiar faces and with shared mores, even as they began to assimilate. Roth commonly describes Weequahic and Newark as a haven or an enclave. In his 1988 nonfiction book, The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography, he writes: “Our lower-middle-class neighborhood of houses and shops—a few square miles of tree-lined streets at the corner of the city bordering residential Hillside and semi-industrial Irvington—was as safe and peaceful a haven for me as his rural community would have been for an Indiana farm boy.”

Roth later recalls summer nights in Newark as he and his friends wandered his neighborhood: “When the weather was good we’d sometimes wind up back of Chancellor Avenue School, on the wooden bleachers along the sidelines of the asphalt playground adjacent to the big dirt playing field. Stretched out on our backs in the open air, we were as carefree as any kids anywhere in postwar America.” In The Plot Against America, a 2004 novel that imagines how Weequahic’s Jews might have fared if Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh had been elected president in 1940, the young Philip, the book’s narrator, says of his street: “Tinged with the bright after-storm light, Summit Avenue was as agleam with life as a pet, my own silky, pulsating pet. . . . Nothing would ever get me to leave here.”

Jews had even more of a stake in such enclaves than other ethnic and religious groups. Italians, Irish, Germans, and other immigrants came to America largely seeking economic opportunity. Many maintained ties with their homelands; by some estimates, as many as 60 percent of immigrants from the Great Migration returned home. But most Jewish immigrants were fleeing persecution and political chaos in central Europe; they had no homeland or waiting families back in the Old World. His grandparents, Roth writes in The Facts, left Europe “because life was awful; so awful, in fact, so menacing, or impoverished or hopelessly obstructed, that it was best left forgotten.” Roth acknowledges that act of forgetting as something that separated Newark’s Jews from many of its other immigrants. In The Plot Against America, he writes that “though Ireland still mattered to the Irish and Poland to the Poles and Italy to the Italians, we retained no allegiance, sentimental or otherwise, to those Old World countries that we had never been welcome in and that we had no intention of ever returning to.”

This reality helps explain why assimilation was so important for the Jews of Newark, even as they struggled to retain an ethnic identity. Roth describes this tension in American Pastoral as “the contradiction in Jews who want to fit in and stand out, who insist they are different and insist they are no different.” In the same book, he shows that assimilation is winning out. He sees assimilation in “their finished basements, their screened-in porches, their flagstone front steps,” by which many of Newark’s American-born Jews are “laying claim like audacious pioneers to the normalizing American amenities.” Roth is at his comic best recounting how Weequahic residents commingled new American traditions with their traditional ethnic identities. In his 1969 novel Portnoy’s Complaint, the students of Weequahic High—its gleaming new facility the pride of the neighborhood in Roth’s youth—took a traditional American schoolboy sports cheer and made it their own:

White bread, rye bread,

Pumpernickel, challah,

All those for Weequahic

Stand up and hollah!

In the otherwise bawdy novel, Alexander Portnoy wistfully recalls accompanying his father on Sunday mornings to watch the local men—including the dentist Wolfenberg, Biderman the candy-store owner, and Sokolow, the prince of the produce market—play that distinctly American game, softball. “I cannot imagine myself living out my life any other place but here,” Portnoy remembers thinking as he sat in the bleachers. “Living forever in the Weequahic section, and playing softball on Chancellor Avenue . . . a perfect joining of clown and competitor, kibitzing wiseguy and dangerous long-ball hitter.” There’s an irony in those lines, which the reader knows comes from a boy growing up to be the ambitious Alexander, who does leave Newark, a city too small to satisfy his aspirations and adult appetites.

The conflict that haunts Alex—who cherishes memories of a secure, almost idyllic, child’s world in a city that he left behind—gives Roth’s Newark novels much of their dramatic tension. Newark in the mid-twentieth century remained a place of opportunity for striving newcomers; but for those who wanted more than their parents and grandparents, it was also a narrow place of limited prospects. In a 1989 essay, Roth describes the conflict as “the alluring dream of escaping into the challenging unknown and the counterdream of holding fast to the familiar.” Roth felt this conflict himself and often explored it in his writing. Some of his most memorable characters, like Klugman in Goodbye Columbus, Murray Ringold in the 1998 novel I Married a Communist, or Bucky Cantor in Nemesis, stay in Newark, come what may, while others, like Swede Levov in American Pastoral or Ira Ringold in I Married a Communist, move on—and sometimes wind up longing for the sense of family and community they’d left behind.

The core of Newark’s sense of community cohesion, Roth shows, was the family—a word that appears perhaps even more than “Weequahic” in his writing. “I am the luckiest man in the world. And lucky because of one word,” Swede’s father, Lou, a successful entrepreneur, says in American Pastoral. “The biggest little word there is: family.” In lines like this, Roth echoes his own father. In The Facts, Roth writes that his father’s repertoire of conversations was easy to sum up: “family, family, family, Newark, Newark, Newark, Jew, Jew, Jew.” Not as an afterthought, Roth adds: “Somewhat like mine.”

Though The Plot Against America is a fantasy, it contains what may be Roth’s most accurate descriptions of life in Weequahic—no surprise, since he draws on his real family to tell the story. “We were a happy family in 1940,” he writes. “My parents were outgoing, hospitable people, their friends culled from among my father’s associates at the office and from women who along with my mother had helped organize the Parent-Teacher Association at newly built Chancellor Avenue School.” Roth evokes the family in Weequahic as “an inviolate haven”—there’s that word—“against every form of menace.” Family breakup was so rare that Roth “knew no child whose family was divided by divorce.” When a character falls short in Roth’s world, his narrators often conclude that some sort of family failure is at least partly to blame. In Indignation (2008), Newark-born Marcus Messner, attending an Ohio college in 1951, attributes the sexual aggression of a college coed to the fact that her parents are divorced. “There was no other explanation,” he thinks. The only justification that Portnoy can think of for the behavior of a kid named Mandel—the only local boy he knows who wears his hair in a duck’s ass, smokes cigarettes, and rides in stolen cars—is that his father died when he was ten. “And this of course is what mesmerizes me most of all: a boy without a father,” Portnoy says.

Roth’s narrator was right to be struck by a fatherless boy in the Newark of that time—and not just in Weequahic. It was a different world. According to the 1950 census, about two-thirds of Newark’s adults were married with children, and single-parent households were rare. Today, by contrast, only about one-quarter of Newark’s adults are in married families with children; seven out of ten kids in the city live in single-parent households.

What knits together the families of Roth’s Newark are adults—some foreign-born but many the children of immigrants—who either experienced the insecurity and deprivation of the Old World themselves or heard stories about it from their own parents. What they want most is to find stability in a neighborhood, in a city, and in a country that offers them the chance at security for their families. Roth paints this generation almost heroically in the sacrifices that its members make for family and community. “It was work that identified and distinguished our neighbors for me far more than religion,” he writes. Remembering his father, a Metropolitan Life employee during an era when agents went door-to-door selling insurance and collecting monthly premiums, Roth told an interviewer in 1991 that Herman toiled six days a week and most nights, and “brought Newark into our house every night. He brought it in on his clothes, on his shoes. . . . He brought it in with his anecdotes, his stories. He was my messenger out into the city.”

In The Plot Against America, Roth similarly depicts the other fathers he saw in Weequahic: “The neighborhood men either were in business for themselves . . . or the proprietors of tiny industrial job shops . . . or self-employed plumbers, electricians, housepainters and boilermen—or were foot-soldier salesmen like my father, out every day in the city streets.” These men, Roth recounts, “worked fifty, sixty, even seventy or more hours a week.” Their wives took on every other family task. “The women worked all the time . . . washing laundry, ironing shirts, mending socks, turning collars . . . cooking meals, feeding relatives, tidying closets and drawers . . . paying bills and keeping the family’s books while simultaneously attending to their children’s health, clothing, cleanliness, schooling, nutrition, conduct, birthdays, discipline and morale.”

Success follows for many of them, and Roth’s books provide a road map to how the children of the Great Migration found the American dream. American Pastoral’s Lou Levov goes to work in a tannery at 14, founds a small handbag maker in his early twenties, goes bankrupt in the Depression, starts up a secondhand leather-goods firm a few years later, begins manufacturing again using expert Italian immigrant workers in Newark, and then lands government contracts during the war and cracks the big department stores on his way to prosperity. Ben Patimkin in Goodbye Columbus is a “tall, strong, ungrammatical” businessman with a knack for negotiation. He makes a great success out of a kitchen-and-bathroom-sink supplies company, hatched in Newark during the era of the Great Migration, earning enough to move his family into Short Hills—a suburb west of Newark once described by Time as the richest town in America—where his kids spend much of their time at an exclusive country club. These men are blunt about their accomplishments. When the Newark riots threaten his factory, Levov gives an angry speech that, if Roth wrote it today, would clearly be seen as a rejoinder to Barack Obama. “I built this [business] with my hands! With my blood! They think somebody gave it to me? Who? Who gave it to me? Who gave me anything, ever? Nobody! With work—w-o-r-k! But they took that city and now they are going to take that business and everything I built up a day at a time, an inch at a time, and they are going to leave it all in ruins!” Only slightly less passionately, Ben Patimkin tells Neil Klugman, “A man works hard he’s got something. You don’t get anywhere sitting on your behind, you know. . . . The biggest men in the country work hard. . . . Success don’t come easy.”

Readers knowing only Roth’s early works, especially Portnoy’s Complaint, might find these later declarations of affection for family, Weequahic, and Newark odd. Roth began as a young writer satirizing—sometimes savagely—nearly everyone from his youth. He depicted parents and older relatives as suffocating and hopelessly out of date, while simultaneously deprecating the younger generation as grasping and shallow. For that harsh portrayal, he faced consider- able criticism from the Jewish community—even finding himself denounced by rabbis in weekly sermons. Early in his career, the anger grew so intense that Roth said that he was done writing about the old neighborhood.

Yet when Roth later returned to Newark in books like the 1991 nonfiction work Patrimony: A True Story, or the novels American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, The Plot Against America, and Nemesis, he tells a more sympathetic story of his father’s generation, which he had come to see—especially after his father’s death—as the crucial link in the assimilation of the Great Migration’s descendants. “They had a task, an American task, and a particular cultural burden,” Roth noted in 1991. “Newark is the battleground, one of many cities in this country, on which the struggle took place. The job they had was to stand between the European family of their immigrant parents and the American realities of their younger children. They were a generation of negotiators, of constructors.”

Nothing illuminates this shift better than the bookends to Roth’s career, Goodbye Columbus and Nemesis. Though each story’s central figure is a young Weequahic man who chooses to stay in the city, Roth invests Nemesis’s Bucky Cantor with a heroic mission—a nearly fatal devotion to Weequahic kids during a polio epidemic—strikingly different from the aimlessness of Neil Klugman in Goodbye Columbus. Further, while both men enter relationships with women from families well above their respective stations, the Steinbergs in Nemesis are portrayed as modest, despite their wealth, proud of their daughter’s relationship with Bucky, and steadfast during the epidemic—a far more flattering portrait than the one Roth drew of the nouveau riche Patimkins half a century earlier.

Roth’s later Newark writing presents an uncompromising account of the city’s sad decline. In Patrimony, Roth writes of visiting old neighborhoods and finding that “what in my childhood had been the busy shopping thoroughfares of a lower-middle class, mostly Jewish neighborhood were now almost entirely burnt out or boarded up or torn down.” Roth’s fictional alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman, makes an impromptu trip to the old neighborhood in the 1981 novel Zuckerman Unbound and observes, “But for candles, incense, and holy statuary, nothing seemed to be for sale anymore on Lyons Avenue. There didn’t seem to be anywhere to buy a loaf of bread or a pound of meat or a pint of ice cream or a bottle of aspirin. . . . Their little thoroughfare of shops and shopkeepers was dead.” Murray Ringold stays in Newark to live and teach in I Married a Communist. But at the end of the novel, he reveals that his wife, Doris, was murdered in the city. “We should have moved. We didn’t, and that’s the story.” Swede Levov sits at his desk in American Pastoral at the family’s Newark business, which he’s refused to relocate out of the city despite his father’s imprecations, and beholds the riots: “Springfield Avenue in flames, South Orange Avenue in flames, Bergen Street under attack, sirens going off, weapons firing . . . looting crowds crazed in the streets.” Later, Swede tracks down his fugitive daughter, working on one of Newark’s most “forsaken” streets, “as ominous now as any street in any ruined city in America,” he thinks.

Such passages have earned Roth censure for “a willingness to stereotype post-1965 Newark,” as one Marxist critic puts it. For critics like this, the tale of Newark’s decline is the familiar narrative of bigoted whites fleeing to the suburbs as blacks arrived in the city, leaving the new residents to fend for themselves in a dying urban landscape. But Roth’s stories reject the easy, conspiratorial view that Newark and other cities started to die because of a plot against them by government planners in favor of growing suburbs, exacerbated by white racism. In Roth’s novels, Newark’s Jews are on the move long before government-financed highways stretch into the suburbs or civil unrest wracks their city. And Roth makes clear that they’re following the grown children of German and Irish immigrants, who’ve already decamped in search of sprawling homes, big backyards, and other outward signs of the American dream. “I own those trees,” Swede thinks as he ponders his estate in rural New Jersey in American Pastoral. He finds it astonishing “that a child of the Chancellor Avenue playing field and the unbucolic Weequahic streets should own this stately old stone house in the hills where Washington had twice made his winter camp during the Revolutionary War.”

Neil Klugman in Goodbye Columbus, which Roth wrote during the 1950s, describes the same process from the perspective of someone who stays in the old neighborhood: “The old Jews like my grandparents had struggled and died, and their offspring had struggled and prospered, and moved further and further west, towards the edge of Newark, then out of it, and up the slope of the Orange Mountains, until they had reached the crest and started down the other side, pouring into Gentile territory.” Living with an aunt and uncle—representatives of the vanishing community—Klugman begins an affair with suburban Brenda Patimkin from Short Hills, a woman already so thoroughly Americanized that she describes her mother as sometimes acting as if “we still live in Newark,” a remark Neil resents. By contrast, Neil’s aunt balks when she hears that her nephew is dating a suburban girl: “Since when do Jewish people live in Short Hills. They couldn’t be real Jews believe me,” she says. Roth’s Newark portraits remind us that the Great Migration ended with the federal immigration restrictions first enacted in 1924. That helped to undercut the next generation of growth in places like Newark long before the city’s neighborhoods erupted in the sixties. Klugman anticipates the decline, wondering even in the 1950s where the new Newarkers would come from. “Who would come after the Negros?” Klugman asks. “Who was left? No one, I thought, and someday these streets, where my grandmother drank hot tea from the old jahrzeit glass, would be empty.”

It would be wrong to reduce Roth to being a mere ethnographer or historian of urban decline. What emerges most clearly in his Newark tales is an exuberance for storytelling, an almost obsessive need to get down on paper “that really rich Newark stuff.” A striking example is Roth’s narration in I Married a Communist of the tale of the canary’s funeral, an incident that attained legendary status in Newark—my grandmother, who witnessed it in 1920, told me about it many times. Immigrant shoe- maker Emidio Russomanno kept a canary named Jimmy in his shop for years. When the bird died, Emidio was so struck with grief that he organized an old-fashioned funeral ceremony, replete with marching bands and a white casket, carried through Newark’s old First Ward by an honor guard of pallbearers. Roth describes the procession (once deemed the world’s largest pet funeral by the Guinness Book of World Records) in great detail, cataloging the numerous local institutions—from churches to well-remembered neighborhood stores—that the procession passed by as it wound its way through the city, attracting a crowd of 10,000. Roth places young Ira Ringold, the novel’s central figure, at the funeral, though the only point he makes is that Ira, whose mother had recently died, was the sole spectator who didn’t see the humor in the whole affair. It’s a thin pretense for an anecdote that goes on for pages; but then, Roth never needed a pretense for spinning Newark yarns.

Referring to himself in the third person as he ponders his career, Nathan Zuckerman, through whom Roth so often spoke, ruminates in Zuckerman Unbound: “All he wanted at sixteen was to become a romantic genius like Thomas Wolfe and leave little New Jersey and all the shallow provincials [behind].” But as it turned out, “he had taken them all with him.”

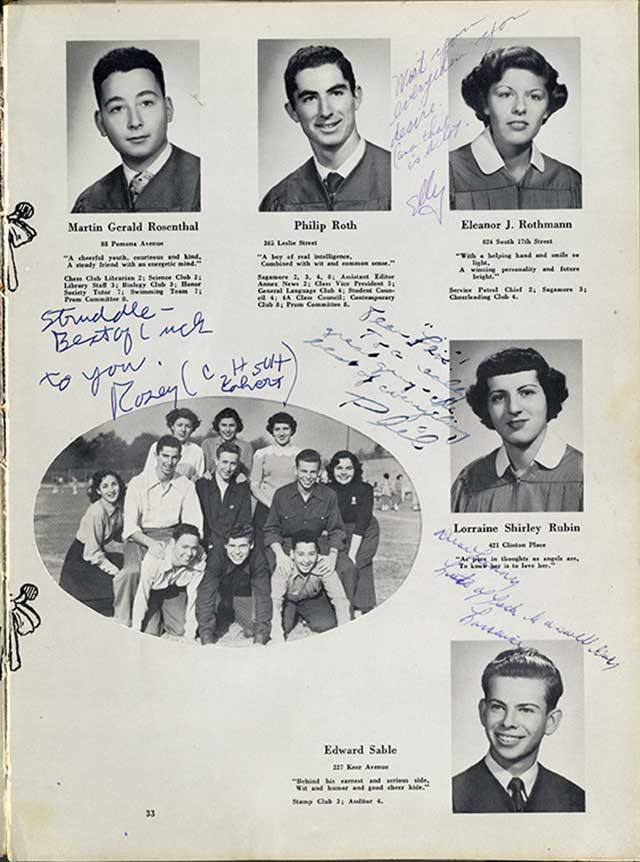

Top Photo: Roth writes often about his alma mater, Newark’s Weequahic High School, where the sons and daughters of immigrants forged American identities. (PHOTO COURTESY OF THE JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF NEW JERSEY)