Belkys Rivera wept as her English translator conveyed her words to the New York City Council in February. “I remember my heart breaking when hearing the news. The last day I saw my son alive was December 25, 2011.” Josbel was 23, starting a new store-management job. Belkys worried when he didn’t come home. “Nunca,” she responded when asked if she had expected to see two detectives on her doorstep at dawn. “The police asked me to get my other children nearby, and that’s when I began to realize that something had happened. The detectives were heartbroken as well, and they were explaining through [my] younger children what happened.” Josbel was dead—killed by a hit-and-run driver while crossing the Bronx’s Mosholu Parkway. “The driver . . . left the scene and burned the car,” she said. “I did my job as a mother,” she added, but “because of an atrocity committed by a man who should not have been driving”—the driver’s license had been suspended—“the world will be denied Josbel’s contribution.”

Amy Tam’s story was just as wrenching. She told the council about her three-year-old daughter, Allison Liao, who sang “The Wheels on the Bus Go Round and Round” as she rode the Q44 bus and who loved “using upside-down laundry baskets as drums”—and who died last fall, “holding Grandma’s hand,” after “a huge SUV” abruptly turned into a Main Street crosswalk in Flushing, Queens, and struck her. “We are never going to see her start kindergarten,” Tam lamented.

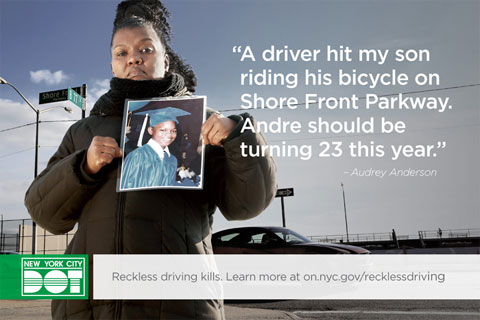

Too many New Yorkers die every year because of reckless drivers. Thankfully, new New York mayor Bill de Blasio has shown leadership in this area, unveiling an ambitious and workable plan to make traffic safer. Backed strongly by New York Police Department chief William Bratton and the city council, the mayor’s multiagency initiative, called Vision Zero, will seek to reduce traffic deaths in the city to zero, just as the police try to cut murders to zero. The inspiration behind the plan, which reinforces and expands on efforts by Michael Bloomberg’s administration, comes from Sweden’s use of innovative road design and smart law enforcement, which has reduced overall traffic fatalities in Stockholm by 45 percent—and pedestrian fatalities by 31 percent—over the last 15 years. When a child runs after a bouncing ball into a residential street and a speeding car strikes and kills him, the Vision Zero philosophy maintains, the death shouldn’t be seen as an unavoidable tragedy but as the result of an error of road design or behavioral reinforcement, or both. We already think this way about mass transit and aviation. These days, a plane crash or a train derailment is never solely explained by human error (a train conductor falling asleep, say); it also is a failure of a system that allowed a mistake to culminate in disaster. Of course, engineers and regulators can’t eliminate all injuries and deaths; but by applying rigorous, data-based methods, they can cut down on them dramatically.

Nobody favors road deaths, but Vision Zero won’t be an easy sell. Implementing it will require working out complex power issues between city hall and Albany, as well as transforming public attitudes. Even in New York, teeming with pedestrians and traffic, many still view speedy driving as an entitlement. Drivers will need to realize—and here, better engineering, law enforcement, and education will be crucial—that getting behind the wheel in a dense urban environment is very different from seizing liberty on the open road.

New York City has already come a long way in reducing traffic fatalities, it’s important to recognize. Last year, New York suffered 288 crash deaths, including 170 pedestrians. That sounds bad, and it is, but in 1990, New York had 701 traffic deaths, with 366 pedestrians killed. And 20 years before that, the city saw nearly 1,000 traffic deaths in a single year; it wasn’t unusual to lose 500 pedestrians annually. New York’s current traffic-fatality numbers compare favorably with other American big cities. An Atlanta resident is more than three times more likely to die in a traffic crash (adjusted for population); a Los Angeleno faces twice the risk. But New York remains behind—in some cases, far behind—other global cities in this area of public safety: Paris, London, Hong Kong, and Tokyo are all less dangerous. A citizen of Stockholm—the gold-standard metropolis for traffic safety—faces just a third of a New Yorker’s risk in dying by vehicle. Last year, the Swedish city, with a population of 900,000, suffered only six traffic deaths. The Gotham equivalent would be 60 such fatalities—not nearly five times that number.

New York City’s improved numbers have resulted in part from state-level policy reforms. New York was the first state to get a seat-belt law, in 1984, a controversial measure at the time—the governor of Maine vetoed a similar bill, saying that it “crosse[d] the line between public interest and personal choice”—but a major lifesaver. New York was also a pioneer in fighting drunk driving. More than half a century ago, everyone, including most public officials, thought it was perfectly okay for people to drink and drive. The legal limit for blood-alcohol content was 0.15 percent, nearly twice today’s limit, and enforcement was nonexistent. A handful of New York State leaders—above all, health chief William Haddon, Jr.—sought to change this blasé attitude. As Barron Lerner, author of One for the Road, a history of drunk driving, recounts, Haddon headed the first state health department driver-research center, in 1954, and it soon found that half the drivers involved in single-car crashes in New York’s Westchester County had blood-alcohol levels above the 0.15 limit, and another 20 percent had levels of at least 0.05 percent. By 1960, thanks in part to Haddon’s visionary work, New York lowered the legal limit to 0.10 percent (it’s now 0.08). During this same period, New York also became the first state to enact an “implied consent law,” which revoked the licenses of drivers who refused to submit to alcohol tests. And police stepped up enforcement while numerous public campaigns targeted drunk driving.

Countless lives have been saved. In Mississippi or Louisiana, you’re two and a half to three and a half times more likely to die in a car crash than in New York State, in part because it’s still more culturally acceptable in those Southern states to get plastered and hit the road. Nationwide, 13 percent of drivers are drunk when they kill a pedestrian. In New York City, 8 percent of vehicular killers are inebriated.

Haddon, it’s worth noting, was one of the first public-health researchers to think of auto crashes as predictable and preventable rather than as random tragedies. “Haddon had come to deplore the use of the word accident, which he believed made automobile crashes sound inevitable, and, by implication, not preventable,” writes Lerner. His approach was to figure out who—and what—was causing deaths on the road, and then work to prevent the fatalities.

Over the past half-decade, New York City has pursued that vision aggressively, seeking to determine who and what continues to kill on the road. Despite media focus on taxi crashes, the city found, 79 percent of New York’s killer drivers are behind the wheel of their own private car or truck, not a commercial vehicle. Most of the drivers are male. In pedestrian deaths, vehicle speed and driver inattention are major culprits. As a recent analysis of five years’ worth of crashes by the city’s department of transportation concludes, “in 53 percent of pedestrian fatalities . . . dangerous driver choices—such as inattention, speeding, failure to yield—are the main causes of the crash. The pedestrians in these cases were following the law.” Three-year-old Allison Liao’s grandmother was following the law when the SUV killed the little girl. The MTA bus driver who hit and killed 23-year-old Ella Bandes on January 31 “was looking in the mirror to try to avoid a taxi at this complicated, pedestrian-unfriendly intersection,” her father, Kenneth Bandes, told the city council; his daughter wasn’t “texting or talking on her phone,” as some people often assume of crash victims. In another 17 percent of pedestrian deaths, a driver error—often excessive speed—made a pedestrian’s mistake a death sentence.

Make no mistake: speed is lethal. Someone hit by a car going 20 mph will live, 90 percent of the time; someone hit at 40 mph has only a 30 percent chance of surviving. Speeding distorts the judgment of both driver and potential victim. “Drivers overestimate their own ability to stop” and “underestimate the impact” of a crash, says Rune Elvik, a civil-engineering professor at Denmark’s Aalborg University. Drivers wrongly think that they’ll save a lot of time by speeding on free stretches of otherwise clogged roads (lights or traffic eventually slow them down). And a child crossing the street has difficulty judging a fast-moving vehicle’s distance. A 2010 paper by the University of London’s John P. Wann and colleagues found that “children . . . could not reliably detect a vehicle approaching at speeds higher than approximately 25 mph.”

Mayor Bloomberg’s transportation commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, used her authority over street design to try to reduce speeds and sharpen driver attention. Times Square’s now famous pedestrian island, filled with tables and chairs, and similar islands and protected bike lanes that Sadik-Khan set up across the city give drivers something to notice, reminding them that people live and work where they’re zooming along. Streetscape changes like these often narrow traffic lanes, as well, which tends to make drivers more careful and makes it less likely that pedestrians will get stuck in oncoming traffic as they rush to cross a street—they can now can take refuge on the islands. Other Sadik-Khan changes included “countdown clocks,” which show crossing pedestrians how many seconds they have before a light turns green, and “split-phase” green lights, which let pedestrians cross before cars and trucks get to turn—a response to the fact that left-turning drivers disproportionately kill.

The numbers show the effectiveness of the design changes. At modified intersections, fatalities have fallen by a third since 2005, twice the city rate. Redesigning Jackson Avenue in Long Island City, Queens—a very dangerous road—by extending medians, painting new crosswalks, and delaying turns cut crashes with injuries by 63 percent. Building a pedestrian island and adding crosswalks on Macombs Road in the Bronx reduced deadly crashes by 41 percent. “Pedestrian-oriented designs save lives,” says Polly Trottenberg, de Blasio’s transportation commissioner.

De Blasio’s Vision Zero project will keep up the Bloomberg-era engineering efforts to change driver behavior, focusing on 25 key “arterial” streets, wide avenues like Queens Boulevard (long called the “Boulevard of Death” for its many traffic fatalities) and the Bronx’s Mosholu Parkway, where Josbel Rivera died. These roadways make up just 15 percent of Gotham’s streets—but 60 percent of the city’s traffic-related fatalities occur on them. The arteries “were designed for the fast movement of cars and trucks,” says Trottenberg, and making them look less like highways will slow drivers. To get the job done, though, de Blasio must be willing to take the heat, as Bloomberg did, for imposing changes that a vocal minority will strongly resist. It’s not a good sign that the mayor, in his February press conference on Vision Zero, wouldn’t say whether he thought that redesigning Times Square had been a good idea.

The smart use of data is a second crucial component of Vision Zero. De Blasio is directing his taxi regulators to explore outfitting taxis with “black boxes,” which can record data and sound warnings when drivers go too fast. The devices could not only deter drivers from breaking the law but could also give the city more data on who speeds, and where. The police could use the information to deploy manpower and the transportation department to redesign dangerous intersections. And Commissioner Bratton says that improved data collection and presentation in all areas of NYPD activity, including traffic enforcement, will be a major goal of his second term as the city’s top cop. That Bratton’s NYPD takes traffic safety seriously was evident in its recent flyers warning drivers that illegal double parking, by reducing visibility and forcing bicyclists into traffic lanes, put innocent people in harm’s way. In March, police officers were out in force ticketing drivers who had parked in bike lanes, pleasing street-safety advocates who had long complained of lax enforcement.

In addition to road design and data crunching, the de Blasio administration will take a more traditional approach to combating speeding: reducing city speed limits. Lowering limits was “the most important” step that Sweden took two decades ago in its traffic-safety turnaround, says Stockholm mayor Sten Nordin, whose city helped pioneer Vision Zero. New York will ask Albany, which controls many of the city’s laws, to let it cut the city’s default speed limit—the maximum speed that drivers can move when they’re not on a highway—from 30 mph to 25 mph. And the city wants to set up more “slow zones,” where 20 mph is the top speed. “The standard in densely populated cities where Vision Zero has been implemented around the world” is 20 mph, Amy Cohen, whose son, Sammy Cohen Eckstein, died on Prospect Park West last year, reminded the city council.

The real challenge will be enforcement. “His memorial is still up,” says Cohen of the site where her son died, yet people still speed there. Deterring such lawbreaking will mean ticketing speeders more aggressively, as well as revoking recidivist speeders’ licenses. After a series of high-profile traffic deaths this winter, the NYPD has been nabbing more speeders and other reckless drivers. The police wrote 7,648 speeding tickets in January, up 20 percent from last year.

An NYPD-led traffic-ticketing blitz runs into problems as a permanent strategy, though. As City Council Member James Vacca notes, “Since 2001, the highway division has been cut by 50 percent. Local resources are stretched.” De Blasio is adding some officers but not nearly enough to make up for past cuts. Moreover, enforcement is inconsistent and incomplete. Thus, Elvik argues, “there are advantages in using automated enforcement”: speed cameras. “There is a much higher risk of detection” with cameras, he adds, and they make for “a fairer system. Speed cameras treat all drivers equally”—even drivers with public-sector union stickers on their cars, for example, whom police tend to treat leniently. The unpredictability of “ticket blitzes” also angers the public. Over time, people appreciate consistency and predictability. If you know that you will always pay a price for driving 10 miles over the speed limit, you probably won’t speed.

Speed cameras are common in cities with better safety records than New York’s. A decade ago, London was only 29 percent safer than New York for pedestrians, relative to population size; now, with lots of cameras in place, it’s twice as safe. “London has a pretty decent network of speed cameras,” says Bruce McVean of Movement for Liveable London. “It makes it a lot easier for local authorities.” London’s transport authority estimates that the cameras help save 500 people annually from death or severe injury. And after New York City started ticketing red-light runners two decades ago, serious injuries at the targeted intersections fell 25 percent; more red-light cameras would improve on those safety gains.

New York politics have made speed-camera use tricky, though. Albany, not city hall, controls the number and placement of the city’s speed cameras, just as it controls the speed limit. Last year, the city won the right to install 20 speed cameras only after a protracted campaign, which benefited from then-mayor Bloomberg’s support, including his shaming of three state senators who had stalled legislation. “Maybe you want to give [their] phone numbers to the parents of the child when a child is killed . . . so that the parents can know exactly who’s to blame,” the mayor said. This year, Mayor de Blasio secured Albany approval for an additional 120 cameras. The power the mayors won is limited, though. The city can only use the cameras to enforce the law on roads that run past schools, and during school hours, though drivers have the most opportunity to speed at night, when there is less traffic congestion. The fine for exceeding the speed limit by at least 10 mph isn’t high: $50. And speed-camera tickets don’t result in penalty “points” on a lawbreaker’s driver’s license—a significant omission, since drivers with too many points for violations can temporarily lose their licenses. As part of Vision Zero, de Blasio wants Albany to relinquish its right to dictate the number, placement, and use of cameras.

Albany will probably resist. First, police unions hate cameras, fearing that they will make human officers redundant. “Ridiculous,” says Paul Steely White of the Transportation Alternatives advocacy group. There would still be plenty for cops to do in traffic enforcement—stopping drivers and levying fines and points for failing to yield to a pedestrian, say, or for texting behind the wheel. Another, more reasonable, charge is that cameras will just become another way for the government to shake people down for revenue. The city and state must combat this perception. “The sole purpose of traffic law should be to prevent harm,” says Leonard Evans, a research veteran of the auto industry and author of the book Traffic Safety. As a way of easing concerns, the city and state could announce that they would split camera-ticket money equally among all New Yorkers via a rebate on their tax return. Expanded camera use should actually shrink revenue over time, as drivers learn to obey the rules. Privacy is a third concern. As Evans notes, though, driving is a public activity, monitored by police for a century now, and traffic cameras “record only people who are breaking the law.” Anyone who uses an E-ZPass already has his movements tracked. A fourth obstacle is the state’s dislike of “home rule.” New York governor Andrew Cuomo isn’t known for giving up power, and de Blasio is pushing for home rule on multiple fronts, from the minimum wage to rent regulation. De Blasio would be wise not to take an all-or-nothing approach, as he did for a time in his battle with Cuomo over a proposed city income-tax surcharge to fund a prekindergarten program.

When a cabdriver runs over a little boy in a crosswalk, or an SUV driver mounts a sidewalk and plows into someone, the public reaction is: the driver should be behind bars. But he’s not. As Karen Friedman Agnifilo, chief assistant district attorney in Manhattan DA Cyrus Vance, Jr.’s office, says: “It can be difficult for people to understand why a crash is not always a crime.” For one thing, in 1990, the state’s appeals court ruled that, as Agnifilo puts it, “an unexplained failure to perceive” on the part of a driver—absent some outrageous conduct—“is not a crime.” In other words, a driver really can say “I didn’t see him” and walk free under the law, even if he had been driving irresponsibly.

New York law currently limits vehicular homicide or assault charges to drunk-driving cases. Several states, though, including Illinois and Florida, now make it possible to charge sober drivers with homicide if they kill. New York does let prosecutors charge for criminal recklessness. Vance is willing to use this law aggressively, as he did in charging Adam Tang, who allegedly videotaped himself trying to break the speed record for motoring around Manhattan. The question is whether juries will accept that driving dangerously is similar to driving drunk.

New York unquestionably needs tougher penalties for deadly driving. “Look at these sentences,” says Agnifilo, pointing to two 2013 vehicular-homicide cases in the city. One defendant got a maximum of four years; the other, six. “Do these sentences seem long enough to you?” Without stiffer punishments for drunk offenders like these, it’s hard to justify longer sentences for other forms of careless driving; the maximum penalty for criminal recklessness is a year. State Senator Mike Gianaris and Assemblywoman Marge Markey of Queens have introduced a bill that makes it a felony if someone with a revoked or suspended license injures or kills someone with a vehicle. Senator Joseph Addabbo, Jr., a cosponsor, observes that, over the last five years, license-less drivers have killed 181 people in New York City crashes—and largely gotten away with it. Under the bill, they could face four years in prison. The measure not only targets a particularly lethal set of drivers; it also could help change public attitudes by making it clear that operating a potentially deadly machine on roadways is a privilege. A related proposal empowers police and prosecutors to seize the plates from a car or truck operated by a driver without a license before he crashes. City hall, backed by several local lawmakers, is asking Albany for several other legal changes, including increasing the punishment for fleeing a crash—one year in prison—so that it’s equivalent to the four-year penalty, practically speaking, for inflicting a drunk-driving injury or death. As Juan Martinez, general counsel at Transportation Alternatives, explains, the driver who hit Josbel Rivera faced a more serious charge (arson) for torching his car than he did for leaving Rivera to die.

Agnifilo says that the NYPD’s “crash investigation squad” now responds to crashes that result in death or “critical” injury. That’s an improvement over two years ago, when the police investigated crashes only when victims were “likely to die.” She would like to see them respond to crashes that cause “serious” injury, the standard for criminal charges. In that case, “district attorneys would be called to more crash scenes, allowing prosecutors to make more appropriate charging decisions,” she says.

To prepare cases, the DA relies on witness testimony as well as subpoenaed cell-phone and text records and, increasingly, thanks to a new federal law, on black-box evidence from cars. Agnifilo wants some straightforward changes from Albany to give prosecutors more resources to prepare their cases. Prosecutors need the right to draw blood at the scene of a serious crash without a warrant, which can take hours to secure—while the driver detoxes. The DA’s office would like more time, under “speedy trial” requirements, to prepare vehicular-homicide cases—as it gets for other homicide cases.

Prosecution of smaller infractions can serve as another deterrent. Thanks to better police enforcement, the Manhattan DA received 2,556 drunk-driving cases last year, up 18 percent from 2009. Though the charge is only a misdemeanor, it can mean thousands of dollars in legal costs and a license suspension, as a current public-service advertisement reminds potential drunk drivers. Here, too, tighter laws could complement better police enforcement and prosecution. Currently, if you rack up two DUI convictions in five years, you lose your license for six months. Cuomo wants anyone convicted of drunk driving twice in three years to lose his license for five years. “Three strikes, and you’re out and you are off the road, period,” the governor said this winter.

The most potent factor in making Gotham traffic safer is that citizens and lawmakers are starting to demand change. “We’re reaching a point of critical mass on the pedestrian safety issue,” says Gianaris. The senator says that after two Queens deaths—eight-year-old Noshat Nahian and Angela Hurtado, an older woman on her way to play bingo—caused by drivers with suspended licenses, he grew angry. “This should be a felony.”

New York is a city made up of powerful special interests, and now a grim new lobby has organized itself: family members of crash victims. Parents, including Amy Cohen and Amy Tam, have helped create Families for Safe Streets, encouraging the public to push for speed cameras and other traffic-safety measures. Lerner, the historian of drunk driving, whose own nephew, Cooper Stock, died on the Upper West Side in January after a cabdriver struck him in a crosswalk, says that the movement is similar to the early movement against drunk driving. “Angry parents and relatives” highlighted “the absurdity of a society” that looked the other way as drunk drivers killed. Just as you now know that you shouldn’t drink and drive, texting and driving should be equally taboo. “As more and more potential distractions for drivers emerge, we should be less—not more—tolerant of a mind-set that excuses such behaviors because ‘everybody does them,’ ” says Lerner. The politically active New Yorkers who show up to community meetings to pressure city council members and Albany legislators on bread-and-butter issues are starting to view dangerous driving as one of those issues. Parents want their kids to get to school safely; elderly people perceive themselves as vulnerable.

Those demanding safer streets expect local government to use better data and smarter engineering and enforcement to achieve that end. Many observers once contended that the murder rate would never fall, but thanks largely to smart policing, it is down 85 percent since 1990—nearly twice as big a drop as traffic deaths. New Yorkers are thus likely to hold de Blasio to his stated goal: a quick and marked reduction in traffic deaths. “We are thrilled that the mayor is so supportive,” says Amy Cohen. But she and her fellow grieving parents, grandparents, siblings, uncles, and aunts will be “a public force” if “things aren’t moving along as expected.”