For once, Donald Trump was guilty of understatement. “Our airports are like from a Third World country,” he complained during the first presidential debate, describing the experience of landing in New York. He was echoing a common complaint—Vice President Joseph Biden had previously used “Third World” to describe La Guardia—but Trump wasn’t adequately diagnosing the problem. Comparing New York’s airports with the Third World’s is unfair to the Third World.

Even in the poorest countries, a traveler can expect to reach an airport terminal by automobile, but the traffic congestion at La Guardia has gotten so nightmarish that passengers are jumping from cabs along the highway and schlepping their bags on foot to the terminal. Passengers often rank La Guardia as America’s worst airport, infamous for its leaky ceilings, claustrophobic corridors, and seedy bathrooms. Yet, by some measures, it isn’t even the worst local airport. As dingy as it is, La Guardia can’t match Newark Airport when it comes to gouging passengers, who’ve seen their fares rise and rise to cover the most expensive landing fees in the country. In the Third World, people typically can fly out of their home city, but prices are so high at Newark that northern New Jersey residents often drive two hours to Philadelphia to find affordable flights.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Why are passengers paying so much to get so little? Because American airports are terribly managed, by global standards, and New York’s airports are the worst-managed in America. Among the world’s top 100 airports, as determined by the annual Passengers Choice Awards, the highest-ranked American airport is Denver—in 28th place, far behind the major airports of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. New York has the second-busiest airport system in the world—only London handles more travelers—but its best airport, JFK, ranks just 59th. Newark and La Guardia don’t make the list.

Outside the United States, in cities such as London, Paris, Madrid, Zurich, Frankfurt, Rome, Istanbul, Mumbai, Sydney, and Buenos Aires, public-private partnerships are transforming the industry, with airports getting sold or leased to private-management companies that focus on pleasing passengers. To make a profit, these managers must hold down costs, while enticing customers with lots of flights, competitive fares, and terminals with appealing stores and restaurants. London’s three airports have improved dramatically since they were privatized—first as a single company, and then divided into three separate firms so as to encourage competition. Heathrow, currently eighth in the international ranking, has been so intent on attracting passengers that it built and runs a nonstop express train linking the terminal to central London. To deal with surging demand, its management company is seeking to add another runway, as is the rival company in London running Gatwick Airport.

In the United States, by contrast, airports are still typically run by politicians in conjunction with the locally dominant airlines, which help finance the terminals in return for long-term leases on the gates and other facilities. Keeping costs down and customers happy are not the highest priorities. The airlines use their control of the gates and landing slots to keep out competitors so that they can charge higher fares; the politicians use their share of the revenue to reward supporters, especially the unionized airport workers who contribute to their campaigns.

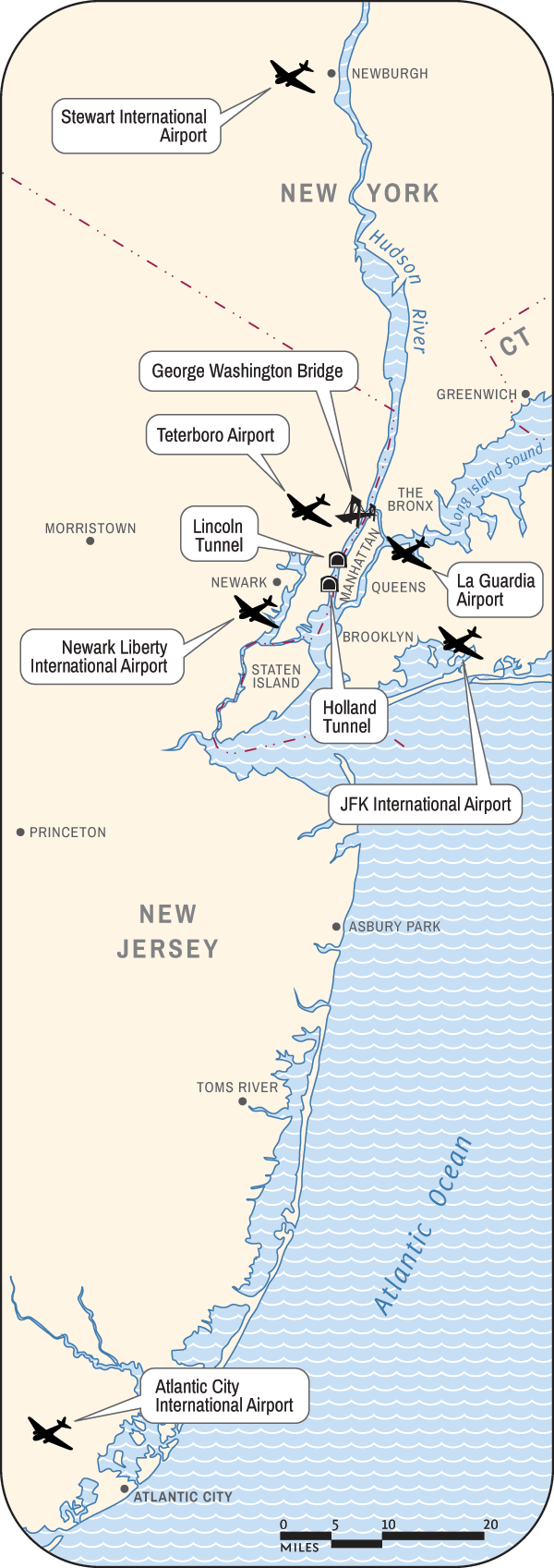

In New York, these problems are even worse because of decisions made in the 1940s to give an airport monopoly to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey—perhaps the most inefficient and least accountable public agency in America. If O’Hare Airport were as dilapidated as La Guardia, Chicago voters could punish the mayor responsible for it. If the San Francisco airport set landing fees as high as Newark’s, it would lose business to Oakland’s airport, which is run separately and competes to attract airlines and passengers. But New York’s three major airports—and three smaller ones—are under the control of an agency that’s unresponsive to voters. No single politician ever gets blamed, because the Port Authority’s executives and board members are appointed by the governors of New York and New Jersey.

When the agency was created in 1921, the rationale for its unwieldy structure was to enable the two states to cooperate on projects to improve the port, starting with a railroad tunnel under the Hudson River. But the agency never built the tunnel. Instead, aided by the Progressive era’s naive faith in rule by independent experts, it became a bureaucracy unto itself, expanding its turf by taking on projects that didn’t cross state lines. On their own, New York and New Jersey could easily have built and managed their own airports, and the competition between them would have benefited the public. If La Guardia were an independent airport, it would pay a price for the traffic mess generated by its current renovation project, which is leading many passengers to shun the airport. But because most of these travelers wind up using JFK or Newark, their money still goes to the Port Authority, anyway. The agency’s managers bring to mind the phone operator on early episodes of Saturday Night Live, played by Lily Tomlin during the Bell-monopoly era: “We don’t care. We don’t have to.”

Freed of competition, the Port Authority has run up its expenses at the airports, chiefly through the above-market salaries and pensions extracted by its politically powerful unions. It spends $156,000 in wages and benefits per worker. (See “Bloated, Broke, and Bullied,” Spring 2016.) Even with these stratospheric costs, the Port Authority charges such high fees that it makes a hefty profit on its three major airports. In most other cities, these revenues would help maintain and upgrade the terminals and runways and other facilities because federal law generally forbids local politicians from diverting airport revenues to non-aviation purposes. But the federal law, passed in 1982, contains a grandfather provision that has let the Port Authority continue diverting billions of dollars of airport money to cover the ongoing losses of its other operations—such as the PATH commuter train from New Jersey to New York, the midtown bus terminal, and the World Trade Center reconstruction project.

“The Port Authority has diverted so much money from the airports that it can’t afford the bill for La Guardia’s renovation.”

That’s the biggest reason New York’s passengers pay so much to get so little: their money isn’t reinvested in the airports. While London’s airports were being modernized, New York’s were allowed to deteriorate. While London’s airports are preparing to add runways, the Port Authority is making no similar efforts to expand capacity in New York, despite the obvious need. It has consigned passengers to long waits in aging terminals, staffed by often unresponsive workers.

The Port Authority’s three big airports rank at the bottom of an analysis of flight delays at major American airports conducted by Nate Silver at the FiveThirtyEight blog. After controlling for weather delays and other factors, Silver calculated how many extra minutes a passenger would be delayed on a typical flight leaving or arriving at each airport. New York’s three airports were the only ones in America with an average delay of at least 19 minutes for both arrivals and departures. The worst was La Guardia, with an average delay of 27 minutes for an arrival and 30 minutes for a departure. The local delays are due partly to the Northeast’s congested skies and to an inefficient air-traffic-control system—also woefully backward, by world standards. But the delays wouldn’t be so bad if New York’s airports hadn’t been stripped of revenue needed to build runways and other facilities to meet rising demand.

New York’s airports also dominated the bottom of the rankings of American airports in surveys of passenger satisfaction by J. D. Power, by the Points Guy, and by Travel & Leisure magazine. La Guardia secured last place, the magazine explained, by having “the dubious honor of ranking the worst for the check-in and security process, the worst for baggage handling, the worst when it comes to providing Wi-Fi, the worst at staff communication, and the worst design and cleanliness.” And that survey was done before the chaos unleashed by the current renovation project.

The Port Authority has diverted so much money from the airports and run up such massive debts on its other projects that it can’t afford the bill for La Guardia’s renovation. That work is being financed partly by Delta Airlines, which is renovating its own terminal, and partly by a private consortium that will build and manage a new central hall and terminal. This public-private partnership with the Port Authority is a welcome development, but it still leaves New York far behind the rest of the world. The private consortium is leasing just one terminal, not the whole airport. And La Guardia is still ultimately part of the same Port Authority monopoly as JFK and Newark. Passengers would be better served by putting each airport under the control of an independent manager, as was done with the London airports.

The successful results in London impressed New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, who moved to break up the airport monopoly in 2000. He criticized the Port Authority for letting the airports deteriorate by diverting $150 million of airport revenue annually into other projects. He proposed reasserting New York City’s control over La Guardia and JFK, which are city property, by ending the Port Authority’s leases and bringing in private managers. The city considered bids from four companies—including the managers of airports in Amsterdam, Düsseldorf, and Zurich—and ended up choosing the British firm in charge of Heathrow. “We drafted an agreement to privatize the airports and began negotiating with the Port Authority,” recalls Anthony Coles, then a deputy mayor. “They were resistant, but we were making some progress on it in 2001.” Then came the attacks on September 11. After that, says Coles, “it wasn’t anyone’s priority anymore, so it never went any further with us.”

The next mayor, Michael Bloomberg, didn’t pursue it, and neither has Mayor Bill de Blasio. But as the airports continue to fall behind the rest of the world, the notion of wresting them from the Port Authority makes more sense than ever. John Schmidt, an attorney at Mayer Brown who has negotiated public-private partnerships at airports around the world, says that plenty of experienced managers are eager for the New York challenge. “When it comes to privatizing New York’s airports,” he observes, “the universal view of the world’s major airport operators is incredulity that it wasn’t done long ago, particularly at La Guardia.” Ever since Margaret Thatcher privatized British airports in the 1980s, that approach has become routine in the rest of the world. Today, three-quarters of passenger traffic in Europe is handled by airports that have been fully or partially privatized. But privatization has been blocked in the United States by federal policies as well as local resistance.

The result has been much poorer management in the U.S., particularly in airports structured like the ones in New York, as a team of economists concluded after analyzing more than 100 major airports around the world. The economists, led by Tae H. Oum of the University of British Columbia, found that airports run by cities or other local governments were typically less efficient than those run either by private companies or by public authorities dedicated solely to the airports. The lousiest airports of all were those in the United States run by port authorities that oversaw both seaports and airports. The economists concluded that Americans should “reconsider ownership and management of airports by port authorities.”

That advice has little appeal to the politicians, unions, and airlines comfortable with the status quo at the Port Authority. But now, there’s an opportunity in Washington to help air travelers in New York and the rest of the country. Donald Trump campaigned on a promise to improve America’s infrastructure, and with Republicans in control of Congress, they can expand their efforts to reform aviation. In the past, they’ve often been stymied in this aim by Democratic opposition, but they do have one success story to build on. If you want to see how much better airports could be in New York, or in any other American city, take a plane to Puerto Rico.

Until four years ago, the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan had lots in common with La Guardia. It was run by an unwieldy bureaucracy, the Puerto Rico Ports Authority, which neglected the airport while running up bills on its other unprofitable projects in the island’s ports. The terminal was a confusing jumble of dim corridors, with passengers enduring long waits to get through security or pick up luggage. The stores were tacky and the restaurants greasy spoons, often rented at bargain rates to politicians’ friends or relatives.

On rainy days, the ceilings leaked; on hot days, the air conditioning faltered. The floors of the boarding bridges from the gates to the planes were riddled with holes. The bathrooms were grimy, and it often took days or weeks to repair a broken toilet. Because of union work rules, changing a lightbulb required four workers, sometimes five—if there was a new bulb available. Some crucial tasks didn’t get done at all, such as maintaining the instrument landing system used to guide a plane descending during bad weather. For years, pilots had to land their planes visually, without positional guidance from radio signals, because the system’s antennae were blocked by trees—and no one in the bureaucracy wanted to take responsibility for cutting them down. Airlines, unsurprisingly, switched operations to other Caribbean hubs, leaving the airport without the revenue to pay bills, much less make capital improvements. There was no hope of rescue from the Puerto Rican government, which was in terrible financial shape during the island’s long-running economic crisis.

The situation got so grim that politicians considered surrendering some of their control over the airport, though that meant sacrificing the patronage that came with it. To dig out of their financial hole, they needed someone from the private sector to pay off their debts and manage the airport efficiently. This solution was difficult to implement in the United States because of obstacles to privatization erected by the major airlines and unions aligned with Democrats. But Republicans in Congress had prodded the Federal Aviation Administration into starting a program that would permit at least a few airports to give it a try.

San Juan became the first—and so far the only—major American airport to make the conversion. The Ports Authority leased the airport in 2013 for 40 years to Aerostar, a partnership of investors and a company operating airports in Cancún and other Mexican cities. The new managers agreed to make capital improvements and to pay the Ports Authority $1.2 billion—half up-front and half over the course of the lease. They also promised to reduce landing fees and keep them low in the future.

The result, just three years later, is an airport that nobody would call Third World. The redesigned concourses are sleek and airy and easy to navigate. Passengers get through security faster, thanks to a state-of-the-art system for screening bags. New boarding bridges stand at the gates. The duty-free shop now looks like an upscale department store, and revenue from the new stores and restaurants has more than doubled. The renovated facilities and the reduced landing fees have attracted more airlines to San Juan, and they have no trouble getting access to gates—now controlled by the airport’s manager, not other airlines. This new arrangement took some getting used to for the dominant airlines, but they’re reaping other benefits.

“We’re paying lower fees for a much better airport,” says Michael Luciano, who has run Delta’s operations in San Juan for almost two decades. “Almost every area has been renovated. You go into any restroom, and it’s bright and clean—things like that are really important to our customers. The lines at the checkpoints are handled more smoothly. The whole airport experience is different. Things work.”

Under the Ports Authority regime, inexperienced political appointees directed the airport; their jobs and plans lasted only as long as their party stayed in power. Now, the airport is run by industry veterans, who take the long view because of their company’s 40-year lease. The Aerostar executive in charge of the airport, Agustín Arellano, a former pilot with the Mexican air force, is an aviation engineer with decades of experience overseeing airlines and airports. “A knowledgeable professional like Agustín makes so much difference,” Luciano says. “With political appointees, you have to teach each new one how the airport works, and it can take so long to get anything done. Now when there’s a problem with a taxiway or a gate or a checkpoint, Agustín understands it and takes care of it right away.”

That’s precisely what Arellano did with the trees blocking the antennae needed to guide planes landing in bad weather. Airport officials had been waiting eight years for bureaucrats in Puerto Rico and Washington to decide which agency had the authority to remove them. Arellano promptly resolved the impasse. “We went out there and cut down the trees ourselves,” he says. “I knew we’d have to pay a fine, and we did—they made us plant two trees nearby for each one we cut down. But we couldn’t wait any longer. We had to make sure planes could land safely. Isn’t human life more important than trees?”

By eliminating old union work rules, the airport has improved services, while shrinking the staff by a third. Managers use new computerized tools for tracking repairs and spotting problems. The airport is one of the first in the United States to install a system that tracks the flow of people throughout the terminal, enabling managers to see exactly how long it takes passengers to get through lines at airline counters and security checkpoints. When bottlenecks occur, extra workers are dispatched to help out.

“We’re trying to change the whole culture of the airport to focus on customer service,” Arellano says. That’s brought more customers. The volume of passengers in San Juan has been growing at 4 percent annually, well above the industry average. That increase is good for Aerostar’s bottom line, of course, but it’s also a boon to Puerto Rico. While the rest of the island’s economy has floundered and the government has cut back services, its airport has transformed from liability into asset. Arellano sees it as a model for New York and other cities, though he recognizes the political obstacles elsewhere. “The airport infrastructure in the United States is so old that there’s no way the government can afford to modernize it all,” Arellano notes. “I realize that the word Ωprivatization≈ is problematic for many people. But it’s not as if the public is giving up all control. It still owns the airport in a public-private partnership. The government gets out of debt and acquires a new source of revenue, and passengers get an improved facility managed by professionals. The public comes out ahead.”

Suppose that the politicians controlling New York’s airports put aside their own interests—this is completely hypothetical, needless to say—and decided to get the best deal for the public. What could be done with the airports?

Robert Poole has looked at the numbers in a report for the Manhattan Institute. A longtime expert on aviation for the Reason Foundation, Poole estimates that the Port Authority could make at least $10 billion, and more likely closer to $35 billion, by leasing the three major airports to private companies. So the long-term leases would probably be more than enough to wipe out the Port Authority’s $21 billion debt—and, even better, wipe out the Port Authority itself. The agency’s other operations—the bridges and tunnels, the PATH train, the World Trade Center transit hub—could be assigned to other managers concentrating on customer service instead of patronage and empire-building.

If the airports were separately managed, New Yorkers would enjoy the same kind of benefits enjoyed by travelers in San Juan and foreign airports: renovated terminals, better services, lower costs, more flights, cheaper fares, more innovation. To reduce congestion and delays, the managers could add another runway at JFK or Newark, or both, and they could use their control of the gates to encourage competition. Like the managers of Heathrow, they might provide a rail link to the center of the city. In no case would they force passengers to arrive at the terminal by wheeling their suitcases along a highway.

It’s a lovely vision, but how—to be non-hypothetical—could politicians be induced to surrender control of the airports?

The first step: prevent them from raiding the airports’ coffers to subsidize pet projects. United Airlines is trying to do this, asking the FAA to stop the Port Authority from diverting its Newark revenue. The airline’s formal complaint details Newark’s “bloated” costs—like the $242,000 in annual compensation per aircraft-rescue worker. It also notes that the airport raises a “staggering” amount of money through landing fees that are “by far the highest” in the country—almost 60 percent more than the next-highest, O’Hare. Much of this revenue goes to outside projects, which the Port Authority claims is permissible because of the grandfathered exemption in federal law. United argues that the agency’s diversions have become so extreme that they’re illegal and should be stopped.

Another strategy would be even more effective: get rid of the grandfather exemption altogether. The Giuliani administration formally asked Congress in 1999 to repeal the clause, so that the Port Authority couldn’t divert money from JFK and La Guardia. But the Port Authority successfully lobbied to keep the exemption.

This year, though, Congress has another chance to do a favor for New Yorkers—and the millions of travelers who pass through. It will be debating aviation policy in order to meet a September deadline for reauthorizing the FAA, which must be done every few years. Now that Republicans control the White House and Congress, they have a golden opportunity to bring American aviation up to international standards. They’re hoping to reduce congestion and flight delays by turning the federal government’s antiquated air-traffic-control system over to an independent corporation, as Canada and Britain have done. They’re also looking to make it easier for airports to emulate San Juan. The FAA’s current program allows just a few airports to experiment with privatization, and then only with the permission of the dominant airlines. If Republicans succeed in eliminating these restrictions and taking away the airlines’ veto power, American airports could start catching up with the rest of the world.

It’s hard to imagine this ever occurring in New York because the Port Authority would be loath to surrender its airport-monopoly profits. (How would it pay for the rest of its empire?) But perhaps President Trump could help. If he really wants to improve his hometown’s airports, he could reprise Mayor Giuliani’s strategy: stop the Port Authority from diverting airport revenue. It can do so now because of the grandfather exemption, but Trump could easily insist that Congress revoke the exemption in this year’s FAA legislation. This would be a painful shock to local politicians, but it could inspire them to think creatively. It might even occur to them to turn over La Guardia, JFK, and Newark to someone who knows how to manage a First World airport.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism. This is the fifth in a series of articles about the Port Authority.

Top Photo: Traffic congestion at La Guardia has gotten so bad that some passengers have to wheel their luggage long distances to terminals. (KATHY WILLENS/AP PHOTO)