Some of the most venerable brands in your grocery store sit not on the shelf but on the checkout line, where magazines like Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Redbook have been reflecting women’s lives for decades. From one month to the next, little seems to vary; the celebrity interviews and fashion spreads blend into one another, creating the impression of a seamless, unchanging world.

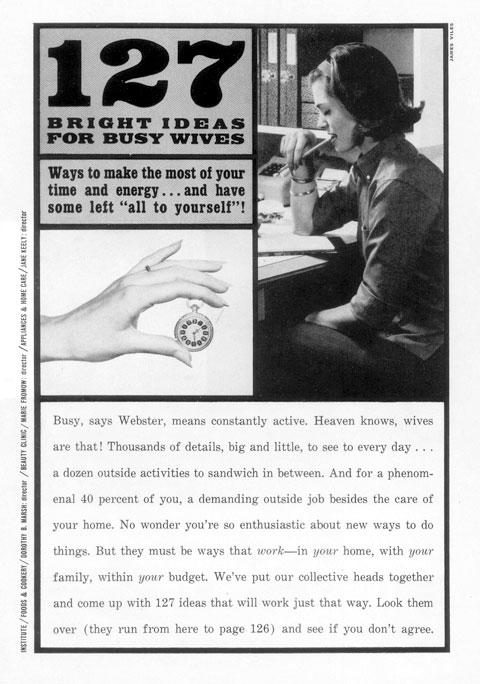

Yet if you compare the women’s magazines of today with their counterparts of 50 years ago, you’ll find it impossible to miss how dramatically different they are—and how daily life has transformed along with them. For example, in 1963, Good Housekeeping could report that 40 percent of its readers were in the workforce; by 2010, roughly 75 percent of women aged 25 to 54 were. In 1963, the average age of first marriage for women hovered around 20.5; by 2012, it had risen to 26.6. Clearly, women’s lives have changed enormously. But a historical journey through the checkout racks suggests that they haven’t always changed in the ways you’d think.

Start with something that hasn’t changed: American women’s obsession with their figures. The January 1963 Redbook featured a cover line on a 10-DAY DIET TO HELP YOU RECOVER FROM THE HOLIDAYS; the February 2013 issue cajoles readers to “get to your best weight ever” and promises “the plan and the push you need.” The April 1963 Ladies’ Home Journal pledged ideas on how to “dine well on 300 calories”; the February 2013 issue offers a more cheerful take on weight control: “Yay! Retire your fat pants forever.” One shudders to think of the pounds lost and gained over five decades of readership.

Given current obesity rates, the readers of women’s magazines were probably thinner in 1963. But their magazines weren’t. Flip through the weighty 50-year-old issues, and you’ll soon feel, literally, a massive cultural shift in what women expect from their periodicals. In 1963, consuming a magazine could take days. Early that year, Good Housekeeping serialized Daphne du Maurier’s novel of the French Revolution, The Glass-Blowers, cramming much of it into a mere three issues. In May, GH ran a large portion of Edmund Fuller’s novel The Corridor, a feat that required stretching the magazine to 274 text-heavy pages. Redbook’s March 1963 issue featured Hortense Calisher’s novel Textures of Life and five short stories, a level of fiction ambition that even The New Yorker rarely attempts now. There is verse, too. At one point, a dense page of du Maurier’s text makes room for Catherine MacChesney’s “From the Window,” letting Good Housekeeping readers experience poetry and prose at the same time. Marion Lineaweaver’s ode to the coming spring in LHJ (“The wind is milk / So perfectly fresh, cool / Smooth on the tongue”) was one of six poems in the March 1963 issue alone.

That erudition is all the more surprising when you consider that women’s magazines reached a far larger fraction of the population in 1963 than they do now. Good Housekeeping hit a circulation of about 5.5 million readers in the mid-1960s, at a time when there were about 50 million women between the ages of 18 and 64 in the country. Ladies’ Home Journal reached close to 7 million readers. Editors assumed, then, that a hefty proportion of American women wanted to ponder poetic metaphor.

Apparently, those women also wanted to read serious nonfiction. Betty Friedan’s manifesto The Feminine Mystique, widely credited with launching Second Wave feminism, was helped in its quest for bestseller status when women’s magazines like LHJ ran prepublication excerpts. In March 1963, Redbook covered a doctor’s agonizing decision to leave Castro’s Cuba after becoming disillusioned with the socialist revolution. GH’s May 1963 issue ran “A Negro Father Speaks,” in which Luther Jackson, a Washington Post reporter, described the racism that his family had experienced and tried to dispel some myths that the magazine’s mostly white readers might have believed about their black fellow citizens. Luther recalled being “angry and humiliated” when a little girl, seeing him on the street, shouted, “There’s a colored man, there’s a colored man!” But he also noted that his own four-year-old had once shouted, “There’s a man with no legs!” when encountering an amputee. What is hatred, and what is merely unfamiliarity? Adding their own comment to this nuanced analysis, the magazine’s editors attached a sidebar to the piece, noting that Luther “feels, and so do the editors of Good Housekeeping, that increased understanding among all people will enable children to live in a world far different from the one known to generations before theirs.” Keep in mind that this was in the spring of 1963—before the March on Washington, before the Civil Rights Act, before the “Freedom Summer.”

Redbook’s January 1963 issue provides further evidence that the editors of women’s magazines felt no fear of controversial topics. The previous year, actress Sherri Finkbine had famously traveled to Sweden for an abortion after learning that thalidomide might have injured her unborn child. Redbook’s top cover line, HOW THALIDOMIDE TURNED A PREGNANCY INTO A NIGHTMARE: SHERRI FINKBINE’S OWN STORY, pointed the reader to a lengthy article called “The Baby We Didn’t Dare to Have.” The editors’ note in that issue discussed efforts to legalize abortion—following up, the editors noted, on a report in Redbook’s August 1959 issue about how many doctors broke abortion laws. The magazine was trying to shape the national conversation. Even its story about counseling parishioners delved into big issues. “Our modern knowledge of psychology and psychiatry,” wrote Ardis Whitman, “is no obstacle to religion but has in fact driven the minister to inquire more deeply into the meaning of human personality than ever before.” What is sin, the article asked, and what is mental illness? Are ministers trained to treat both?

These are deep questions suggesting a deep interest in the world. So it’s jarring—to the 2013 reader, at any rate—to read the how-to articles that the meaty features and novels are sandwiched between. In GH’s March 1963 issue, Helen Valentine’s monthly column, The Young Wife’s World, tried to answer a young woman who had written to ask: “Just what is good housekeeping? What needs to be done daily, weekly, monthly?” Though much depended on the woman and her house, family, and temperament, Valentine responded, “I would say that any home needs to be straightened up every day—dusted, ash trays emptied, beds neatly made, clutter cleared away.” What’s the most surprising part of that sentence to our modern ears—emptying ashtrays? At the time, about 40 percent of adult Americans smoked, far more than today’s 19 percent.

Or are we more surprised by the idea of daily dusting? According to sociologists Suzanne Bianchi, John Robinson, and Melissa Milkie in Changing Rhythms of American Family Life, married American mothers spent close to 35 hours per week on housework in 1965. (One of Friedan’s stories for Ladies’ Home Journal was “Have American Housewives Traded Brains for Brooms?”) The magazines assumed that their readers were competent at sewing and needlework; the February 1963 GH featured instructions for knitting a coat that was a “weightless classic of mohair, matchless for the bright-lights mood of a night on the town, just as stunning by day.”

Indeed, the homemaking standards were sometimes almost comical. In March 1963, Good Housekeeping ran 500 words on how to wax a floor. A time-saving tip: “To apply a paste polishing wax, spread a small amount on the waxing brushes with a butter knife.” Perhaps less amusing is another article in that issue called “A Spanking-Clean Nursery” (people still spoke of spanking in polite company). “No one needs to tell a mother that the room where baby sleeps should be immaculate,” the story began. “But many mothers say they would like to know more about how to keep a nursery in this pristine state.” The young mother was instructed to “wet-mop the floor at least once a week. Dry-mop it daily and be vigilant about wiping up spills and splashes after you feed or bathe the baby.” The mother should also keep a large sponge handy to clean the crib, windowsills, and woodwork.

Such a regimen of floor-waxing and dusting could quickly eat up the time that a mother could have used to play with her children. In 1965, married mothers spent just 10.6 hours per week on child care as a primary activity, according to the same trio of sociologists. That included 9.1 hours of “routine activities,” such as bathing and dressing, and a mere 1.5 hours of “interactive activities”—the reading, playing, and chatting that we now think of as quality time.

Then there was cooking. All get-togethers required baked goods, and not of the supermarket-cookie variety. The 1963 housewife apparently lived in terror that neighbors might stop by unexpectedly for coffee and that she wouldn’t have a spread ready. To solve just that problem, the March 1963 issue of GH offered recipes for a “quartet of coffeecakes” that could be made ahead of time and frozen. March’s Good Housekeeping described a “molded three-fruit salad” made with mayonnaise, cream cheese, heavy cream, canned pineapple, and canned Royal Anne cherries.

All that was missing was any sense of how long these recipes would take. “The assumption was that you had that kind of time,” says historian Stephanie Coontz, director of research at the Council on Contemporary Families. “Once the kids got off to school, you could spend the rest of the day cooking if you wanted.” Some women with too much time on their hands—those with older or grown children, for example—might have welcomed the devotion that cooking demanded. The promise of women’s magazines was that “we can keep you busy 20 hours a day—if you chop the celery very fine for that lime Jell-O salad,” says Coontz.

Perhaps that explains why the magazines advertised so many convenience foods, from Campbell’s soups to Hunt’s tomato sauce to Duncan Hines brownies, and nevertheless printed recipes that incorporated those easy elements into complicated dishes. One LHJ story from April 1963, “The Magic of Mixes,” noted that “every mix is a bagful of tricks. Each ‘instant,’ canned and frozen food too.” All these foods were “excellent as is,” the article conceded, “but look what happens when they become an ingredient. Our Beef Cottage Pie, for example, begins in a box—or rather boxes, plural—then materializes as hearty, fork-tender chunks of beef in a magic gravy (dry soups are the secret).”

Over the past 50 years, as women have poured into the workforce, the amount of housework that they do has cratered. By 2000, say Bianchi and her colleagues, married mothers were devoting 19.4 hours per week to it. But the amount of time that they were spending with their children rose to 12.9 hours a week, including 3.3 hours spent on “interactive activities.” Many mothers consequently feel pulled in many directions at once. Not long ago, a WorkingMother.com poll asked readers when they’d last had “me time.” About 50 percent of respondents claimed that they couldn’t remember (though you have to wonder when, exactly, these busy women find the time to answer online polls).

Maybe that’s one reason that today’s women’s magazines are so short. The February 2013 Ladies’ Home Journal runs just 104 pages. The longest features top out at six pages, and they’re graphics-heavy. No longer do editors view their product as something that you’ll curl up with for hours over the course of a month. Instead, a magazine is something that a woman-on-the-go can grab to fill those scarce snatches of “me time”: 15 minutes of waiting for the kids at soccer practice, or 20 minutes on the bus to work.

The articles in today’s women’s magazines seem to be written explicitly for this “me time”—that is, centered on the reader herself and not on the larger world. After reading through the 1963 magazines, one can’t help finding the modern ones a bit shallow. It’s hard to imagine a social revolution being launched from their pages, as Friedan’s partly was. Only a few features deal with something beyond the reader’s own life—a tale in LHJ, for instance, of how the mother of a soldier killed in action met the nurse who treated him. Gone (mostly) are the short stories and the novels. In the 1963 Redbook, the anthropologist Margaret Mead answered outward-facing questions from readers (“Do very primitive societies have humor?” “Do you believe that our laws on drug addiction should be revised?”). In the 2013 Redbook, a similar role is filled by Soleil Moon Frye, the actress best known for playing Punky Brewster, who answers readers’ personal questions—one about a husband’s body odor, another about a fiancé’s pre-wedding jitters. Remember the January 1963 Redbook that told the anguished tale of Sherri Finkbine’s thalidomide exposure? The February 2013 issue looks at sexual health from a different perspective. One of its longest stories, hawked on the cover as BIRTH CONTROL THAT BOOSTS METABOLISM? SIGN US UP!, features women discussing why they switched contraceptive methods, with such headlines as SHE LOST THE EXTRA WEIGHT and HER LIBIDO IS BACK IN BUSINESS! Redbook writer Erin Zammett Ruddy reports that “as with so many things (sex life, hair, marriage), you don’t have to settle for so-so birth control.”

Even the staid Good Housekeeping has gone you-you-you. It has recently published a book called 7 Years Younger, turning the resources of its product-testing Good Housekeeping Research Institute to the pressing question of the most effective moisturizers. The longest piece in the magazine’s February 2013 issue may sound less fluffy: its news hook is some thought-provoking research from the Templeton Foundation about gratitude. But the piece emphasizes what being grateful can do for you: “New research shows why gratitude is a crucial tool for health and happiness,” the headline promises. A mother of twins explains that she uses her commute to reflect on her blessings because “thinking about what’s made me grateful lets me come into the house with less stress and more positive energy.” A May 1963 Good Housekeeping feature on “what it takes to be a wife, mother and heart surgeon” profiled Dr. Nina Braunwald with an almost anthropological fascination: “She belongs to no organizations, goes to no meetings, spends no time in idle chat.” The February 2013 Good Housekeeping also profiles a doctor, but the reason is that she successfully lost 40 pounds—and that you can, too.

In all this self-obsession, something has surely been lost. Still, what the modern woman finds in today’s Redbook isn’t entirely superficial. Consider the “time budget” that the February issue of the magazine proposes for her day. Her morning should feature an intense work project; she should blog after work because “if you don’t block out time for personal projects and dreams, they’ll never happen”; her evening can be devoted to “family game night!” The point, Redbook notes, is to “prioritize time for activities you love”—which no longer seems to include spending all day reading a magazine.

Top Photo by Jeff Greenberg/Getty Images