Since the 1960s, America has faced an epidemic of serious mental illness that represents a shameful chapter in social policymaking. Hundreds of billions spent on “mental health” programs have left many untreated, fated to eke out a pitiful existence on the institutional circuit of jails, homeless shelters, and psychiatric hospitals. We often take for granted that modern times are gentler than the dark days of the thumbscrew, lynchings, and public executions. Yet we have allowed scores of tormented men and women to suffer and die on city streets every year.

New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reckons that 239,000 adult residents suffer annually from “serious mental illness,” defined as “a diagnosable mental, behavioral or emotional disorder (excluding developmental and substance use disorders) that resulted in functional impairment that substantially interfered with or limited functioning in one or more major life activities.” The best-known serious mental illnesses are schizophrenia and bipolar depression—disorders of thought and mood, respectively. In 2012, more than 90,000 of New York’s seriously mentally ill went untreated.

New York mayor Bill de Blasio has made improving New Yorkers’ mental health a priority of his administration, but his ThriveNYC program repeats too many of the mistakes of the past and will deliver too little assistance to those in greatest need. Promising a “comprehensive solution to a pervasive problem,” ThriveNYC relies on an overly expansive definition of mental health and lacks focus. While de Blasio claims that public confusion about the nature of mental health makes matters worse, his plan will increase that confusion by blurring the lines between mental illness in its serious and mild forms, making too much out of “stigma,” and emphasizing prevention over treatment. De Blasio has committed more than $800 million to ThriveNYC, but these resources are spread too thin, across too many priorities. A better approach would focus more on helping the seriously mentally ill and less on ideological and political concerns.

Before the 1950s, government’s default solution to untreated serious mental illness was long-term care in an inpatient setting. But since then, this approach has been phased out through the process known as deinstitutionalization. Advocates of deinstitutionalization claim that care is more humane and effective—and cheaper—when delivered in communities rather than hospitals. This process, which got its start in the early 1960s, continues today. Under New York governor Andrew Cuomo, for instance, the state Office of Mental Health plans to cut hundreds of beds from its psychiatric hospital network in a questionable effort to develop a “progressive behavioral system.” But in its attempt to solve the problem of too many people staying too long in psychiatric facilities, deinstitutionalization created many new problems—especially in cities. The daily encounter with obviously disturbed individuals milling about train stations, libraries, and parks wasn’t part of ordinary city life prior to the 1960s. Follow-up reporting on subway pushings, “suicides-by-cop,” and other grim tragedies often reveals that the victim or perpetrator had a history of mental illness.

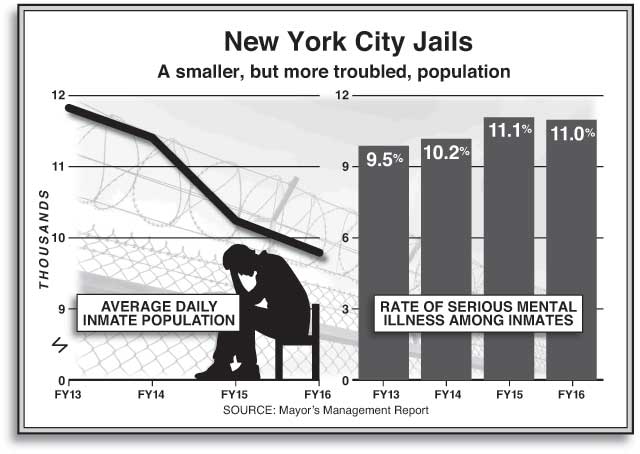

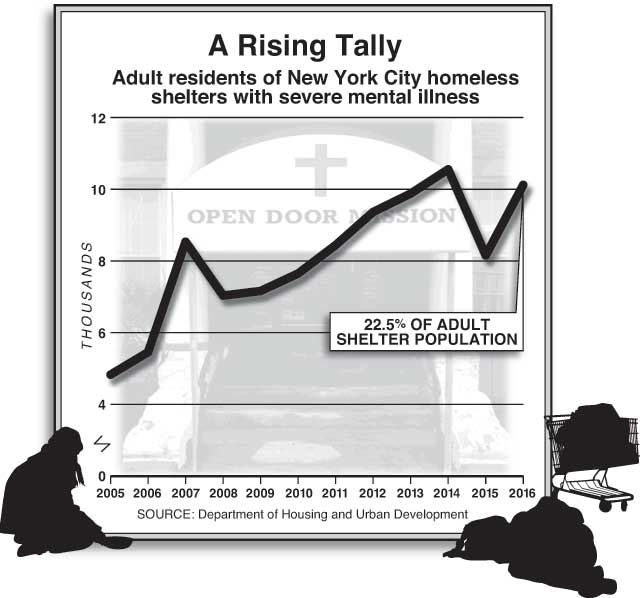

In truth, the mentally ill have not been deinstitutionalized so much as trans-institutionalized. They make up a disproportionate share of our incarcerated and homeless-shelter populations. In New York, 11 percent of city jail inmates are seriously mentally ill, a proportion that has increased even throughout the recent decline in the Department of Corrections’ overall census (see chart below). More than 10,000 clients of New York’s shelter system are severely mentally ill—almost 25 percent of the total adult shelter population (see chart below). The city says that another 1,300 are sleeping on the streets, though the data on which this claim is based are imprecise; the true number of unsheltered homeless with severe mental illness is quite possibly higher.

Dealing with untreated serious mental illness is not, and never has been, the exclusive responsibility of city government in New York. The state wields enormous power through its administration of Medicaid, discretion over which outpatient programs to fund, regulation of civil-commitment standards, and operation of eight psychiatric centers (about 1,400 beds) within the five boroughs. But dating back to Ed Koch, New York mayors have felt the need to do something about mental illness, particularly insofar as it overlaps with the homelessness challenge. Koch tried to expand the use of involuntary commitment for the mentally ill street-homeless population, though the New York Civil Liberties Union thwarted him. Koch’s successors, through a series of agreements negotiated with state government, built thousands of units of supportive housing to help stabilize homeless single adults suffering from serious mental illness.

Mayor de Blasio sees ThriveNYC, which he rolled out in November 2015, as further-reaching than anything that his predecessors had attempted. It was motivated, in part, by his family’s experience with mental illness. De Blasio’s father, Warren Wilhelm Sr., was an alcoholic who committed suicide. The parents of de Blasio’s wife, Chirlane McCray, suffered from depression; and McCray, who has been active in developing and promoting ThriveNYC, has spoken often of her and de Blasio’s daughter’s struggles with “addiction, depression, and anxiety.”

ThriveNYC is a combination of new programs and expansions of existing programs. Following the model of the Bloomberg administration’s antismoking efforts, it takes a public-health approach toward mental illness, with an emphasis on prevention and public education. As spelled out in the “Roadmap” announcing the program: “A public health approach [to mental illness] means that we cannot limit ourselves to advocating for access to treatment. We must also examine why certain communities bear such a disproportionate share of the burden.” ThriveNYC is pitched as a mental health plan for “vulnerable” New Yorkers, but vulnerable is defined more in socioeconomic than psychological terms. The initiative is centrally concerned with increasing access to mental health care for poor and minority New Yorkers—and their kids.

Citing survey data on how many New York schoolchildren feel “sad and hopeless” and consider suicide, ThriveNYC’s administrators want to ramp up mental health services for children attending low-performing public schools, with an eye toward addressing the “root causes” of mental illness. The “Talk to Your Baby” campaign, which “urges caretakers to talk, read, and sing to their babies,” will promote more emotional well-being for children in low-income areas. New mothers at city hospitals and in homeless shelters will be screened for postpartum depression and instructed in “a range of topics, including child development, secure attachment and bonding, safe sleep practices, and breastfeeding.” As ThriveNYC’s advocates see it, more mental health services for children is a preventive strategy. “It is easier to grow strong children than to repair broken adults,” McCray likes to say.

“Prioritizing prevention over treatment has never shown much promise, particularly for the most severe disorders.”

Thus, ThriveNYC elevates promoting mental health over remediating serious mental illness: “What is needed—and what New York City currently lacks—is a major commitment to mental health, one that is backed up by resources that are commensurate to the challenge. . . . And to be successful, that response must assertively support and promote mental health in addition to addressing mental illness” [emphasis in original]. Looking beyond the mere alleviation of suffering, Mayor de Blasio has made flourishing, with respect to mental health, a city-government policy priority—hence the term “Thrive.” ThriveNYC proposes to alleviate a broad range of mental illnesses, not just the serious varieties that afflict less than 5 percent of the population.

Though de Blasio castigates the “legacy of scarce resources, and scarcer attention,” of mental health services under his predecessors, ThriveNYC is working from a baseline of $2.5 billion, a sum greater than the budgets of many city departments, including the sanitation, fire, and parks departments. New York City was already budgeting $450 million for mental health services for schoolchildren; Thrive will pump in an additional $40 million. The initiative’s official $818 million price tag will stretch out over four fiscal years (FY2016–19). The Independent Budget Office estimates that, when fully phased in, ThriveNYC will entail an increase of $230 million in annual spending, with 85 percent of the funding coming from city revenues.

The spending isn’t the main problem with ThriveNYC. Its flaws begin with the de Blasio administration’s misplaced faith in preventing serious mental illness. Prioritizing prevention over treatment may sound savvy, but it is, in fact, an old idea that has never shown much promise, particularly with regard to the most severe thought and mood disorders. A 1960 federal commission charged with conducting “objective, thorough, and nationwide analysis and reevaluation of the human and economic problems of mental illness” found that “[h]ardly a year passes without some new claim . . . that the cause or cure of schizophrenia has been found. . . . The one constant in each new method of psychiatric treatment appears to be the enthusiasm of its proponents.” Firsthand accounts of dealing with a psychotic or deeply depressed family member often report seeing little advance warning of their illness prior to its emergence in the late teen / early adult years. Certain populations are more likely to develop psychoses than others: having a seriously mentally ill family member and living in a city, for instance, are both “risk factors” for psychosis.

Our rough knowledge of the causes of serious mental illness is hard to translate into a preventive strategy along the lines of, say, how the germ theory of disease led to the elimination of cholera (see “Germs and the City,” Spring 2007). The official manual that the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene uses in its “mental health first aid” courses acknowledges that the “causes of bipolar disorder are not fully understood,” and the same can be said for schizophrenia. The manual rightly accents the importance of treating psychosis as promptly as symptoms arise, to prevent deterioration. That’s much different, though, from saying that we’re in any position to prevent it from arising in the first place. As the noted psychiatrist Allen Frances puts it: “Great suffering would be avoided if only we could identify those at risk for schizophrenia and intervene early before they have experienced their first full-blown psychotic episode. . . . But how do you find the needle in the haystack—the rare strange teenager who will go on to be psychotic from the many other strange teenagers who will grow up to be normal?”

ThriveNYC characterizes a focus on treating serious mental illness as insufficiently ambitious—a perplexing attitude, considering how elusive this goal has proved throughout the deinstitutionalization era. Going back to President John F. Kennedy, officials have repeatedly predicted that better outpatient options would obviate the need for institutionalized care. The high rates of serious mental illness among America’s incarcerated and homeless populations attest that these predictions have not been borne out. While some forms of outpatient and community service are more promising than others for certain populations, even the best only go so far (in a typical year, New York City sees 45,000 psychiatric hospitalizations). Yet the de Blasio administration has gone all-in on outpatient options. ThriveNYC makes barely any mention of hospitals, except to argue that low-income minority neighborhoods’ relatively high hospitalization rates are due to inadequate care options in the community.

De Blasio suggests that he will overcome barriers to community mental health care by attacking “stigma.” The city will fund $15 million in “Today I Thrive” ads on television, online, social media, the subways, and bus shelters. This public campaign has two points to make: mental illness can affect anyone; and “seeking help is an act of strength, not weakness.” ThriveNYC fits comfortably in the psychiatric mainstream in its emphasis on fighting stigma.

But this concept has two major problems. First, when it comes to mental illness, the anti-stigma focus can lead, perversely, to overlooking the underlying condition. Obsession with stigma has caused advocates to oppose restricting access to firearms for the mentally ill, to oppose lifting privacy protections so that family members can get access to loved ones’ medical histories, and even to deny that mental illness is an illness. ThriveNYC’s deliberate blurring of the distinction between mild and serious mental illnesses is clearly premised on the supposition that if the public believes that schizophrenia, which affects only about 1 percent of all adults, is the problem, then it won’t support a broader mental health agenda. The effort, then, is to portray mental health (and mental illness) as part of one broad continuum, affecting one and all. The plan’s “Roadmap” opens with a telling quote from an unnamed NYU professor: “It’s all of us. Whether you’re getting hospitalized in the ER or whether you’re feeling unable to get out of bed because of a particular situation that happened the previous day, it’s all of us. There are no exceptions.”

But no amount of such talk can obscure the reality that distinguishing between more and less serious varieties of mental illness is critical—especially if the goal is treatment. As Dinah Miller and Annette Hanson document in their 2016 book Committed: The Battle over Involuntary Psychiatric Care, a hard-core minority of the seriously mentally ill will resist care on a purely voluntary basis and must somehow be coerced into treatment. Figuring out how to do that involves negotiating various legal and moral dilemmas that are orders of magnitude more complex than delivering more mental health services to schoolchildren in poor neighborhoods. About half of schizophrenic individuals and 40 percent of bipolar individuals, it’s estimated, have “anosognosia”: lack of insight into their illness. For this cohort, the largest barrier to treating their illness is their inability to recognize that they have an illness. Fighting stigma won’t help clear that obstacle.

Second, it is difficult to avoid the suspicion that ThriveNYC’s obsession with stigma is intensified by progressive ideology, which sees oppression as somehow at the root of all social ills. Our notion of what “mental illness” is and how to treat it always has been heavily shaped by social norms—far more than our approach to cancer, heart disease, tuberculosis, and other sicknesses. By and large, modern psychiatrists are strongly inclined to condemn the institutionalization era, which many associate with an excessive disregard for patients’ wishes and a custodial form of mental health care. “Stigma” helps psychiatrists retain pride in their profession: the problem isn’t medicine but social prejudice.

Progressives are reluctant to admit that some forms of behavior must be stigmatized in order to preserve the social order. Stephen Seager, a psychiatrist at Napa State Hospital in California, sees anti-stigma campaigns as a textbook case of trying to treat the symptom instead of the disease. “Stigma is a Greek word which means a ‘dot, puncture, brand or mark,’ ” he says. “What is the mark? It’s the often bizarre, psychotic, violent behavior of those so afflicted. This is what marks the serious mentally ill. This is what causes the public aversion. This is what we should be spending money to correct. People will never tolerate bizarre, violent, psychotic behavior. Never have. Never will. To think otherwise is tragically naive.”

Advocates for the seriously mentally ill disagree about whether calling for more resources for mental health services, as de Blasio is doing, will help their cause. Some see distinguishing between more and less severe mental illness as divisive; noting that the overall rate of serious mental illness is in the low single digits, they believe that a bigger tent among advocates is more likely to secure better services for everyone. A handful of de Blasio initiatives focused on the seriously mentally ill would seem to support this view. These include a sharp increase in funding for homeless shelters that serve the seriously mentally ill and for Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training, which instructs cops on how to deescalate encounters with disturbed individuals. Training for CIT entails a four-day, 32-hour course, in which officers hear lectures about how to identify mental illness in its various forms and participate in simulations with “emotionally disturbed persons” played by professional actors. In a sane world, police officers would not be tasked with serving as outpatient orderlies, but NYPD dispatchers have been fielding an increasing number of “emotionally disturbed person” calls; last year, such calls topped 400 per day. CIT is a sensible approach to a reality that is unlikely to change anytime soon. The de Blasio administration has also made good use of Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), or Kendra’s Law, which places the seriously mentally ill under court-ordered treatment programs. The city reports that AOT orders have risen 20 percent since de Blasio took office.

However, in light of societal trends toward overdiagnosis of mental illness (see “Everyone on the Couch,” Autumn 2013), often criticized both by traditionalist conservatives and those on the anti-psychiatric left, it would be naive to assume that increased funding for “mental health” means more and better services for untreated psychotic and manic individuals. An irony of deinstitutionalization is that it coincided with the Great Society, when spending on social policy expanded dramatically. But the problem of untreated serious mental illness gradually got worse because, as E. Fuller Torrey, a psychiatrist and founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center has documented, the “worried well” secured a disproportionate share of the increased spending on community mental health services. This helps explain why, despite mentally ill Americans’ intractable struggles with incarceration and homelessness, annual spending on mental health reaches about $200 billion nationwide.

ThriveNYC promotes diagnostic inflation by citing epidemiological survey data about how “One in five . . . adult New Yorkers experience a mental health disorder in any given year. And that’s a conservative estimate.” These figures reveal more about our society’s views on mental health than they do about a crisis of mental illness “occurring at a staggering rate in New York City.” The point is not that ThriveNYC will benefit “worried well” housewives on the Upper East Side at the expense of manic and psychotic individuals in homeless shelters. Rather, the debate over diagnostic inflation concerns where to set the boundary between a mental disorder and a normal response to adversity. Clearly, youths growing up in the South Bronx are exposed to significant adversity. But having a father in jail, knowing someone who was murdered, or living in a homeless shelter are not mental health problems in themselves. In order to address the “root causes” of any sadness, anger, or anxiety provoked by these experiences, city government should focus on the adversity, not the psychological response to it. That will require different policies from those we need to help truly psychotic individuals. By conflating these two challenges, the de Blasio administration leads New York away from a solution to both and arguably does harm to inner-city neighborhoods by undermining the resilience that youths must develop to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty.

ThriveNYC is insufficiently attentive to the needs of the hardest cases—namely, chronically disturbed New Yorkers who’ve burned their bridges and thus lack family supports, and who resist most offers of treatment. The program’s most glaring missed opportunity is supportive housing. By providing subsidized rents and wraparound social services, supportive housing can enable some mentally ill individuals to live a life of qualified independence in the community and thus fulfill the original promise of deinstitutionalization. Over time, though, supportive housing in New York City became a victim of its own success. Because the policy had worked so well in stabilizing the seriously mentally ill homeless starting in the 1980s, the administrations of New York mayor Michael Bloomberg and New York governor George Pataki began expanding its reach to other homeless cohorts, such as substance abusers and youths aging out of foster care. At 15,000 units, Mayor de Blasio’s supportive housing plan is the largest in city history, but because he has expanded eligibility to even more groups than Bloomberg did—such as the disabled and domestic-violence victims—he has made it more likely that the seriously mentally ill will once again be victimized by mission creep.

“New York would be better served by a policy that focused more on addressing untreated serious mental illness.”

That a progressive administration’s mental health plan will fail to target maximum resources toward New Yorkers with the greatest mental health needs may sound surprising—but only for those unfamiliar with the broader de Blasio agenda. ThriveNYC bears a striking resemblance to the administration’s affordable-housing and universal pre-K programs. By definition, universal pre-K funds services for families who could pay the full freight and don’t need government assistance to prepare their four-year-old for kindergarten. Bruce Fuller of the University of California at Berkeley has found that some low-income neighborhoods are still missing enough pre-K seats, even as the de Blasio program has amply expanded in more affluent areas. De Blasio has taken flak on his left for not allocating more of his affordable-housing plan’s 200,000 units for very low-income New Yorkers. Eleven percent of the “affordable” units projected to come online over the next decade will be made available to middle-income households (those in the $100,000–$139,000 income band). The mayor had his reasons for not restricting pre-K and subsidized housing to the neediest cases, and at least one reason was political. Progressives have long believed that the best way to build broad support for a government program is to extend its reach into the middle class. “A program for the poor is a poor program,” goes the logic, and ThriveNYC reflects that outlook. It thus stands as further evidence that the de Blasio policy agenda is better understood as a broad-based attempt to expand the public sector’s reach than a plan to ensure that the most vulnerable get what they need.

New York would be better served by a mental illness policy that focused more on addressing untreated serious mental illness. To reverse course from ThriveNYC, city government should make three changes. First, it should restore the original purpose of government-funded supportive housing to addressing the intersection of homelessness and serious mental illness. To the extent that other homeless populations need rental assistance beyond basic shelter, this should be provided via affordable- or transitional-housing programs.

Second, the city should advocate for state-level changes, such as revising New York’s civil-commitment law to allow for institutionalization in the case of “grave disability,” a more lenient standard than the “dangerous to self or others” now codified in state law. The city should also call for an end to the state Office of Mental Health’s plan to reduce psychiatric beds. Though Governor Cuomo has touted bed reductions as a money-saver, the move will likely just shift costs to jails and homeless shelters.

Third, city policymakers should stop trying to be “comprehensive.” As D. J. Jaffe, advocate and author of Insane Consequences: How the Mental Health Industry Fails the Mentally Ill, puts it: “100 percent of adults can have their mental health improved” in some way, but that doesn’t mean that suboptimal mental health should rise to the level of a policy priority. For city government, a piecemeal approach that targeted efforts to where the seriously mentally ill slip through the cracks—such as jails and homeless shelters—would do more good than the current attempt to be everything to everyone. This would require curtailing talk of prevention and accepting the less glamorous—but far more daunting—task of treating serious mental illness where it already exists. Doing that comprehensively and well would be challenge enough.

Top Photo: Deinstitutionalization helped cause New York City’s homeless problem, which mayors going back to Ed Koch have struggled to solve. (WILLIAM E. SAURO/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX)