Jerry Brown’s long political career will likely end in January 2019, when the 80-year-old’s second stint as California governor concludes. In the media’s eyes—and in his own mind—Brown’s gubernatorial encore has been a rousing success. His backers say that he has brought the state back, economically and fiscally, from the depths of the Great Recession, which hit California harder than it did the rest of the country. Brown has enacted an array of left-liberal policies, to the delight of progressives, and positioned California as a blue-state role model for the American future. A decade of phenomenal growth among Silicon Valley’s landmark companies has boosted the state’s image and helped restore its overall economy. Democrats hope that California will provide a template for reestablishing their appeal to voters nationwide.

But the state’s boom shows signs of leveling off: after growing much faster than the national average for several years, the economy, notes a recent report by the Los Angeles Economic Development Corporation, has now fallen to around the national average; the state is no longer generating income faster than its prime rivals such as Texas, Washington State, Oregon, or Utah. California Lutheran University forecaster Matthew Fienup suggests that the state’s economic growth could fall below national norms if current trends continue.

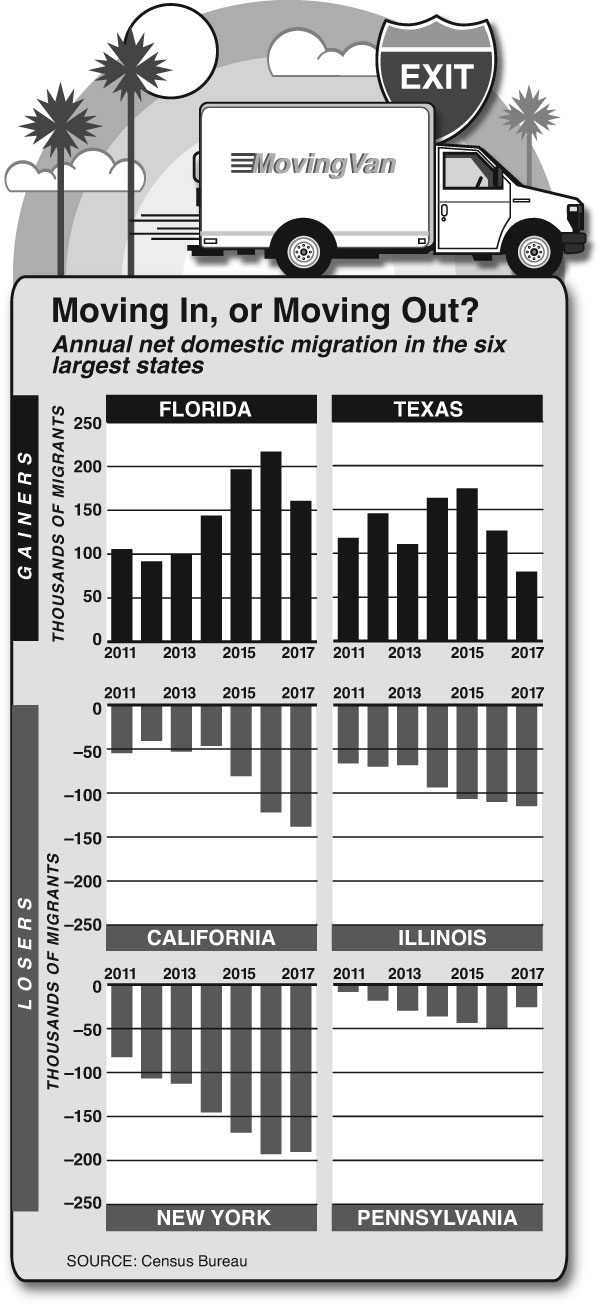

The growth that so impressed over the past five years has masked a multitude of policy sins, and as California’s economic engine slows down, the underlying problems are becoming harder to deny. People are moving out in greater numbers than they’re moving in. Rates of job creation—and the types of jobs being created—vary widely according to geography. The high-tech hubs of San Francisco and Silicon Valley have added tens of thousands of well-paying jobs during Brown’s tenure, but the rest of the state hasn’t done nearly as well.

Brown has put California on a fiscally unsustainable path. A disproportionate share of the funds paying for his ever-expanding progressive agenda derive from Silicon Valley’s capital-gains tax revenues and inflation of the state’s coastal real-estate prices. Any slowdown in the tech money machine or drop-off in property values could prove disastrous for Sacramento’s budget—California gets half its revenue from its top 1 percent of earners. According to Pew, this makes it the major American state with the most volatile finances. Both U.S. News & World Report and the Mercatus Center ranked California 43rd among the states in fiscal health. And that was during an economic boom.

Brown’s departure will also remove the last (if only partial) restraint on progressives in the state legislature, who largely do the bidding of California’s powerful public-employee unions and the green lobby. These forces will pressure the next governor to ram through even stricter environmental laws, more onerous labor regulations, and a single-payer health-care system. California’s teachers are even pushing for an exemption from state income taxes.

California was once ground zero for upward mobility. No more. During the new millennium, the Golden State has become increasingly bifurcated between a small but growing cadre of elite workers and a far larger pool of poorer families barely scraping by. Wide disparities have opened up between the ultrarich and a fading middle class. The Brown administration has largely ignored the state’s poor and struggling rural areas as it pursues its agenda of remaking California into a progressive paradise. The bill—socially, economically, and fiscally—is coming due.

Throughout much of the twentieth century, California was a population magnet, growing ever more economically vibrant as it attracted the ambitious and the entrepreneurial from other American states and from around the world. Now the state’s long-running population growth is leveling off. During the last decade, high taxes, rising housing costs, and constrained economic opportunity have sent many California residents in search of greener pastures. Domestic economic migrants are pursuing their American dreams in low-tax, pro-growth states like Arizona, Nevada, and Texas.

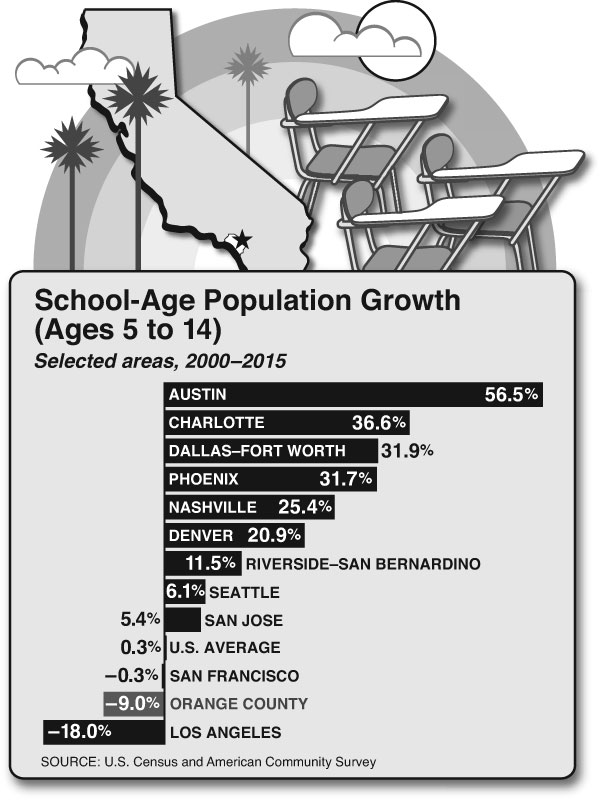

With fertility rates already below replacement, the state’s population growth fell below the national average for the first time last year. Only four states—Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Illinois—are attracting fewer newcomers per capita. Immigration won’t solve that problem—new arrivals from foreign countries have trended down over the past decade. Since 2010, Florida attracted international immigrants at a per-capita rate nearly 70 percent greater than California’s. Net domestic out-migration, which declined in the early years of the Great Recession, tripled between 2014 and 2017. Worse, according to a recent UC Berkeley study, more than a quarter of Californians are considering picking up stakes, with the strongest proclivity found among people under 50.

California is aging, too. The state’s crude birthrate (live births per 1,000 population) is at its lowest since 1907. Los Angeles and San Francisco ranked among the bottom ten in birthrates among the 53 major metropolitan areas in 2015. Between 2000 and 2016, San Francisco–Oakland and San Jose ranked 34th and 47th in terms of millennial growth among the country’s 53 largest metro areas. A dearth of young people would pose particular problems for an economy like California’s, long dependent on innovation, traditionally the province of younger workers and entrepreneurs. Seventy-four percent of Bay Area millennials are considering a move out of the region in the next five years. Since 2000, Los Angeles–Orange County has seen some of the nation’s slowest growth of 25- to 34-year-old residents; since 2010, it has remained substantially below the national average on this measure. The progressive narrative suggests that those leaving California are poor, poorly educated, or both. Yet according to the Internal Revenue Service, out-migrant households had a higher average income than those households that stayed or moved in; even the Bay Area is experiencing growing out-migration from increasingly affluent people. Though the new federal tax changes, which will limit state tax deductions, will likely not affect the wealthiest oligarchs and landowners, they could further accelerate the departure of the merely somewhat affluent.

The current climate contrasts sharply with the 1950s and 1960s, when Jerry Brown’s father, the late Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, pursued dynamic pro-development policies as California’s governor. During those decades, the state constructed new infrastructure that sparked growth in fields as diverse as high-tech, aerospace, fashion, agriculture, basic manufacturing, and entertainment. What was then a model freeway system connected California’s cities to new middle-income communities in the San Fernando Valley, the South Bay of San Francisco, Orange County, and along the spine of the San Francisco Peninsula, which morphed into what we now call Silicon Valley. Pat Brown’s administrations modernized and extended the state’s water-supply system and crafted a public university system that was the envy of the nation, if not the world. Describing Brown’s leadership in transformational terms, biographer Ethan Rarick called the twentieth century the “California century.”

These reforms sparked a long economic boom not only on the California coast but also in the state’s massive interior. In those days, the region had political clout, as Republicans and Democrats competed for votes in Fresno, San Bernardino, and Kern Counties. Today, the California heartland tilts Republican but has lost its influence, as political and economic power has consolidated around deep-blue Silicon Valley and San Francisco.

Like his father, Jerry Brown is a liberal Democrat, yet he has worked overtime to undermine much of Pat Brown’s pro-growth legacy. With the cooperation of a compliant state legislature dominated by liberals, Brown has increased taxes, instituted polices making energy much more expensive in California than in neighboring states, pursued regulations causing housing costs to rise to unprecedented levels, and positioned California as a safe space for illegal immigrants. Brown’s policies embrace the values not of aspirational California but those of its wealthy coastline residents. From water and energy regulations to a $15 minimum hourly wage, Brown’s agenda reflects the ultraliberal political predilections of the Bay Area. That’s where Brown himself lives, as do many of the state’s political elite, including Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom and U.S. senators Dianne Feinstein and Kamala Harris. The rest of the state has been pushed to the political margins and keenly feels its powerlessness. “We don’t have seats at the table,” laments Richard Chapman, president and CEO of the Kern County Economic Development Corporation. “We are a flyover state within a state.”

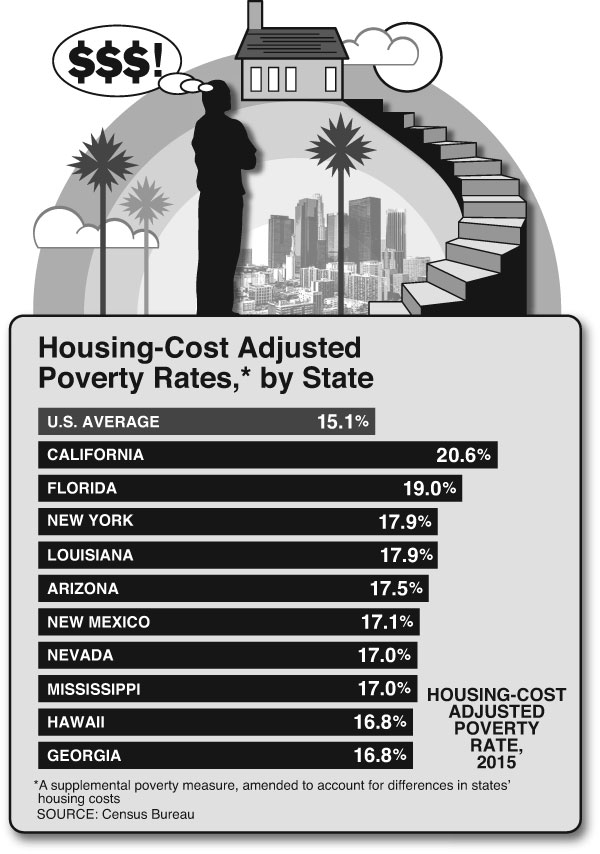

Though widely praised by left-wing think tanks and progressive foreign governments, Jerry Brown’s policies have unquestionably exacerbated income inequality in California. According to the Social Science Research Council, California now has the highest levels of income inequality in the United States. In the last decade, according to the Brookings Institution, inequality grew more rapidly in San Francisco than in any other large American city; Sacramento ranked fourth on this measure. California is home to a disproportionate share of the nation’s wealthiest people, including four of the 15 richest on the planet. Yet more than 20 percent of Californians are considered poor, adjusted for housing costs. That’s the highest percentage of any state, including Mississippi. According to a recent United Way study, close to one in three California families is barely able to pay its bills. Los Angeles, by far the state’s largest metropolitan area, has the highest poverty rate of any large region in the country. In the 4 million–strong Inland Empire, a population nearly as large as metropolitan Boston suffers one of the highest poverty rates among the nation’s 25 largest metro areas.

Between 2007 and 2016, according to an analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the Bay Area created 200,000 jobs paying better than $70,000 annually, but high-wage jobs dropped both in Southern California and statewide. The number of blue-collar jobs, some of which pay well, has dropped by 500,000 since 2000 and by more than 300,000 since the Great Recession. Minimum-wage or near-minimum-wage jobs accounted in 2015–16 for almost two-thirds of the state’s new job growth, according to the California Business Roundtable—and the new $15 minimum-wage law, set to phase in over the next half-decade, will hurt such entry-level employment, research suggests.

The number of high-paying business- and professional-services jobs is now growing at a rate considerably lower in Silicon Valley and San Francisco, moreover, than it is in rising boomtowns such as Nashville, Dallas–Fort Worth, Austin, Orlando, San Antonio, Salt Lake City, and Charlotte. Most other California metro areas, including Los Angeles, are doing far worse when it comes to job growth in this area. The Inland Empire saw a 7 percent loss of such jobs between 2015 and 2016. As for tech jobs, between 2015 and 2017, San Francisco and San Jose added 23,000 jobs in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, for a growth rate of 4 percent and 7 percent, respectively. But the greater Los Angeles area, by far the state’s largest urban center, gained only 6,500 STEM jobs, for a growth rate of just 2 percent, well below the national average. Even worse, the Riverside–San Bernardino area added barely 900 STEM jobs, for a growth rate of about 2 percent.

Blame some of this weakness on the Brown administration, for putting the squeeze on the state’s business community. Brown’s aggressive stance on energy and climate issues—unrealistic renewable-energy mandates and reduction targets for fossil-fuel emissions—has placed California at war with industries such as home building, agriculture, and manufacturing, says economist John Husing. California’s industrial electricity rates are, as a consequence, twice as high as those in Nevada, Arizona, and Texas—the states that have emerged as California’s main competitors for business and residents.

Much of California’s overall job growth—40 percent—during the last decade has been concentrated in the prosperous Silicon Valley and Bay Area, which account for about 20 percent of the state’s population. The majority of the state’s population lives outside the Bay Area and, generally speaking, the farther you go from there, particularly inland, the worse the economic situation gets. Among the nation’s 381 metropolitan areas, notes a recent Pew study, four of the ten with the lowest share of middle-class residents are Fresno, Bakersfield, Visalia–Porterville, and El Centro. Three of the ten regions with the highest proportion of poor people were also in California’s interior. Southern California has lagged its northern rivals, too, leaving whole swaths of the region in poverty.

Many Californians living in the inland areas had hoped that the coastal boom would spill eastward, as skilled workers headed out in search of more affordable living. That’s how it had always worked before. In the 1980s and 1990s, middle-class Californians flooded out of the costly coastal urban centers and into the interior counties, running from Riverside to the Central Valley adjacent to the Bay Area. That flood, though, has slowed to a trickle. Prior to the 2008 housing crash, the Inland Empire annually gained as many as 90,000 domestic migrants, largely from the coast; in 2017, a mere 15,000 relocated.

Housing costs are a likely cause of this slowdown in domestic migration. Since 2009, Inland Empire house prices have increased at a higher rate than that of Orange County, according to data from the California Association of Realtors and the National Association of Realtors. Not that housing is remotely affordable on the coast: a median-priced house in Atlanta, Dallas–Fort Worth, or Houston is between one-half and one-third the cost in the Bay Area or Los Angeles.

Indeed, at their current rate of savings, many young Californians will take 28 years to qualify for a median-priced house in the San Francisco area—but only five years in Charlotte, or three years in Atlanta. And California millennials can’t look to higher salaries to relieve the housing pressure, since, on average, they earn about the same as their counterparts in far less expensive states such as Texas, Minnesota, and Washington. Small wonder that, for every two home buyers who came to the state in 2017, five homeowners left, notes research firm Core Logic.

The unaffordability of homes has had an impact on businesses. Many of California’s biggest non-tech employers have moved their headquarters out of the state in the last five years or are in the process of doing so. In 2014, for example, Toyota announced that it would move its North American headquarters from Torrance to Plano, Texas, just north of Dallas–Fort Worth. The main reason, according to economist Albert Niemi, Jr., of the Southern Methodist University Cox School of Business, was housing costs for 6,500 Toyota workers. Pasadena’s Jacobs Engineering also shipped 700 headquarters jobs to less expensive Dallas–Fort Worth. Occidental Petroleum left Los Angeles for Houston in 2014. Glendale-based Nestlé decamped for Rosslyn, Virginia, in 2017. Amgen, the world’s largest biotech firm, will shift much of its workforce from pricey Ventura County to cheaper Tampa, Florida.

A reduction in the supply of new housing has driven prices upward. New single-family construction in the Inland Empire has dropped to one-third of prerecession levels. California’s statewide rate of issuing building permits—for both single- and multifamily housing—remains well below the national average, particularly compared with prime competitor states, such as Texas. Los Angeles is the nation’s second-largest metropolitan area but ranked sixth largest in new home construction in 2017, building fewer than half the number of new homes built in Dallas–Fort Worth and lagging behind even smaller Austin and Denver.

What’s causing California’s housing crunch? Misguided progressive policies that have slowed housing construction are at least partly to blame. Construction firms, for example, must pay “prevailing wages” when undertaking some new housing projects, raising building costs by as much as 37 percent. Recent new subsidized “affordable” units in the Bay Area cost upward of $700,000 to complete. Urban theorists and planners promote government-enforced “density” requirements on new developments, ignoring data that show high-density construction to be as much as five times as costly per square foot as low-density construction. Those costs make it harder for developers to profit from housing construction, and hence less likely to build, and when they do build, the higher price tag gets passed on to residents. Rent control now enjoys widespread support, but it, too, discourages new housing construction.

California’s dramatic demographic shift has added its own problems to the housing crisis. Since 2010, California’s white population has dropped by 270,000, while its Hispanic population has grown by more than 1.5 million. Hispanics and African-Americans now constitute 45 percent of California’s total population. Almost a third of the state’s Hispanics and a fifth of its African-Americans live on the edge of poverty. Incomes have declined for the largely working-class Latino and African-American population during the economic boom, as factory and other regular employment has shifted elsewhere.

Many minorities in proudly multicultural California live in deplorable housing conditions, with a rate of overcrowding roughly twice the national average. Los Angeles County, with a population more than 50 percent Latino or African-American, has the highest level of households with “severe overcrowding”—defined as at least 1.5 persons per room—of any major metropolitan area in the U.S. Some 25 percent of Los Angelinos, according to a recent UCLA study, spend half their income on rent—another unfortunate metric in which the city comes out on top. And things aren’t looking as though they will improve for many young blacks and Hispanics anytime soon; the state’s poor education system has not served them well, with California’s eighth-grade reading scores ranking among the nation’s worst.

At least those in overcrowded dwellings have a place to live. Even as homelessness has been reduced in much of the country, roughly one-quarter of all homeless people in the nation live in the Golden State, and the numbers are rising. California’s homelessness problem is in part a product of a benign climate, but soaring housing costs are doubtless playing a role as well. Los Angeles County has roughly 55,000 homeless people, up 23 percent since last year. San Francisco, the darling of the tech economy, now has 7,500 homeless people, essentially 160 per square mile. The problem is spreading to traditionally affluent areas like Orange County and Silicon Valley, now site of some of the nation’s largest homeless encampments.

The only way to ensure a just and sustainable California future lies not in giving Sacramento more power but in reducing regulations, allowing localities to control their own fates, building more housing along the periphery, and embracing reasonable standards on environmental controls. According to the Energy Information Agency, since 2007 California has reduced emissions by 10 percent, below the national average of 12 percent; for all its ambitious green laws, the state ranks a measly 35th in emissions reduction. Tougher environmental regulations simply push people’s carbon footprint to other states, where, because of harsher climates, per-capita emissions tend to be higher. Rather than trying to vamp as the leader of a visionary nation-state, as Brown has done recently on trips to Western Europe, Russia, and China, California’s next governor can meet the still-ambitious environmental goals of the Obama administration without doing too much additional damage to the state’s beleaguered middle class.

Last year saw the first signs of a middle-class pushback. A handful of largely Latino and inland Democrats—some backed by the state’s residual energy industry—killed Brown’s attempt to force a 50 percent reduction in fossil-fuel use by 2030, a measure that, opponents alleged, would have necessitated gas rationing. Millennials—faced with diminishing prospects for good jobs and homeownership—could break with progressives and demand a change. They might begin to ask the uncomfortable questions that Californians must answer if they are to avoid bankruptcy: Do we update our water systems, pave our roads, fix our bridges, hire cops, and improve schools—or continue to pay for some of the country’s most lavish green incentives and other costly progressive measures? One recent survey suggests that young people are less likely to identify as “environmentalist” than previous generations. They could conceivably turn to an unconventional figure, like independent gubernatorial candidate Michael Shellenberger, a maverick who threatens to disrupt the status quo by removing barriers to middle-class growth and reviving the Pat Brown legacy.

California needs to recapture the dynamics of upward mobility in a state that once epitomized it. Those of us concerned about a better future for the next generation have reason to be discouraged. But with all California’s resources and its culture of innovation, a way can be found to restore the state’s once-proud reputation as incubator of aspirations and fulfiller of dreams.

Top Photo: Approaching the end of his second stint as governor, Jerry Brown has put the state on a fiscally (STEPHEN LAM/GETTY IMAGES)