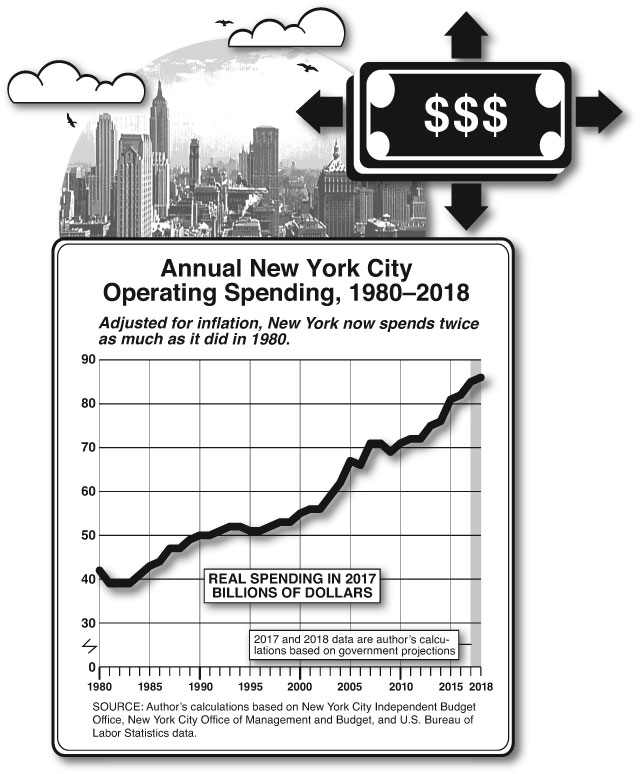

Most of America has had a rough time since the 2008 economic crisis. New York City isn’t most of America. The city is doing strikingly well, repeatedly breaking its own records for job creation, tourism, and tax revenues. But New York also keeps eclipsing another record: spending. When Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in January 2014, New York was halfway through a fiscal year in which it would spend $76.2 billion; during the current fiscal year, which started July 1, 2017, the city will spend about $87.3 billion—an $11.1 billion increase. Thus, Mayor de Blasio’s inaugural term has seen a 14.6 percent rise in annual spending. (All numbers are in today’s dollars.)

New York’s seemingly unshakable economy has given de Blasio the luxury of never having to make any real choices, across four annual budgets. His administration has been able to add 1,550 new police officers and offer prekindergarten, starting next year, to three-year-olds. It has been able to put air conditioning in all the city’s public schools and buy special street sweepers to clean sidewalks. It has expanded funding for opioid addicts and repaired crumbling public-housing facades. And the mayor can claim to have done all this while purporting to be fiscally prudent. In early June, inking a budget agreement with the city council nearly a month ahead of schedule, de Blasio pointed to the city’s budget reserves as “by far the highest the city of New York has ever had.” The mayor has pulled this off, moreover, without succeeding in his efforts to raise taxes, which Governor Andrew Cuomo and the state legislature have thwarted.

Yet behind the no-fuss, no-drama budgeting lurk serious risks. To make his budgets add up, de Blasio has pushed much of the cost for past spending into the future—making it tougher to cut spending while protecting public services in a future downturn. The mayor has added tens of thousands of government workers to the city payroll without tackling the reforms needed to get their future retirement costs under control. And in a record boom, New York is still not putting enough money into critical infrastructure. Finally, Gotham remains dangerously dependent on its top earners to fund its massive budget. If the city’s rich—or, for that matter, the emerging world’s new middle classes, who drive tourism—don’t continue to thrive, de Blasio or a successor will face a record budget crisis.

Contrary to what some of the mayor’s critics—and the mayor himself—say, de Blasio’s free spending marks a continuance, not a change, in city policy. De Blasio won the race to replace Mayor Michael Bloomberg partly by arguing that the billionaire financial-business founder was a miserly mayor, noting in a debate that “we need clear progressive change and a break from the Bloomberg years.” Yet Bloomberg was, by any definition, a believer in expansive government. During his first term, from 2002 to 2006, spending rose by nearly 18.9 percent above inflation. Over Bloomberg’s three terms, spending increased by nearly 31.6 percent faster than inflation.

The real differences are in how the two mayors used the electorate’s money. Both have spent lots on people; personnel costs make up a large percentage of local government expenditures. Of the city’s spending this year, 54 percent—nearly $47 billion—will go toward salaries, wages, pensions, and other employee benefits. Under Bloomberg, though, the bulk of the city’s extra spending on personnel went toward what the former mayor often called “uncontrollable” costs: pensions and health care. Two trends worked against the city, even as Bloomberg didn’t actively seek to increase or decrease costs in these areas. First, the plummeting stock market after 2001, amid rising life expectancy, meant that New York had to put far more money into its public-pension funds to have a chance of paying future benefits. Then, national health-care costs soared. During 2002, New York City spent $5.2 billion a year on pension, health, and other benefits for government workers. By 2014, Bloomberg’s last budget year, the city was spending $17.4 billion on its workers’ benefits—a nearly fourfold increase, even after inflation. These costs accounted for fully one-third of Bloomberg’s higher spending.

As for the rest, Bloomberg styled himself the education mayor, and sizable increases in K–12 education outlays constituted 21 percent of the former mayor’s extra spending. The new money included a 40 percent-plus raise for teachers, something that Bloomberg said was integral to achieving teacher cooperation with his classroom reforms. A rise in social-services spending, including on homeless shelters and Medicaid, made up 12.3 percent of the Bloomberg-era hikes, going from $12.5 billion to $13.9 billion. Capital investment in everything from water-treatment plants to parks also rose significantly, with projects often plagued by cost overruns; debt costs went from $5.2 billion to $6.7 billion, or 7.7 percent of the Bloomberg increase.

De Blasio has been luckier than his predecessor in at least one key way: it helps to take office during an economic boom, not a recession. Global investment markets have done well over the past near-decade, easing the immediate burden on New York’s public-pension funds. Growth in health costs has slowed, too. This year, New York will spend $19.7 billion on pensions and health benefits for current and retired city workers. That’s a remarkable amount of money, nearly one-fourth of New York’s total budget, but the extra cost since the end of the Bloomberg era represents only 21 percent of the city’s new spending.

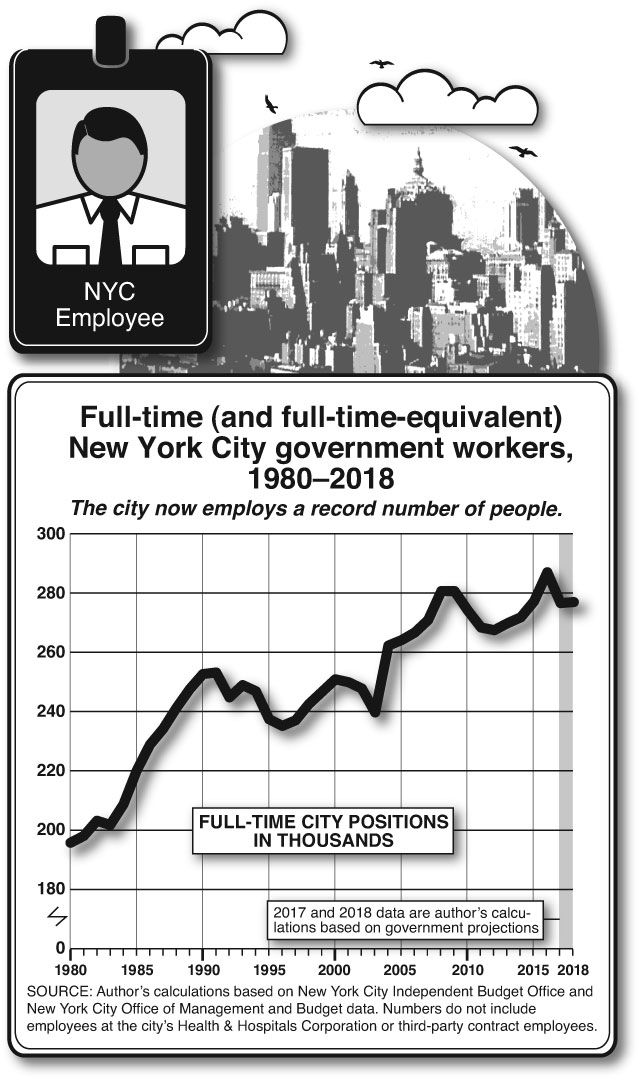

So what is the mayor spending all the extra money on? Structurally, many areas of city spending remain similar. When Bloomberg left office, New York spent 34 percent of its resources on education and 20 percent on social services. Today, even with de Blasio’s expansion of prekindergarten schooling, New York spends 35 percent of its resources on education and 18 percent on social services. But targeted spending hikes do add up. Expenditures on homeless services under de Blasio, for example, have risen from just shy of $1 billion in 2014 to $1.7 billion, a 70 percent increase that hasn’t translated into reduced numbers of homeless people. The city is shelling out a lot more on offices and staff, too—from $781 million to $955 million during de Blasio’s first term, a 22 percent boost. The ranks of government workers also have been swelling under de Blasio, up 6 percent.

De Blasio’s biggest extravagance isn’t in a particular area of the budget, however. It’s his big wage hikes for all city employees, including retroactive raises for the three years before he became mayor. In 2014, New York paid its workforce $22.7 billion in salary and wages. This year, it will pay $27.3 billion—a 20.3 percent increase after inflation that represents nearly half of de Blasio’s increase in spending. Teachers have been the biggest beneficiaries; salaries in the education department rose from $9.7 billion to $11.5 billion, or 18.6 percent, while the ranks of education employees rose just 5 percent. But the mayor has richly compensated New York’s uniformed workers, as well, pushing up pay for firefighters, police officers, corrections officers, and sanitation workers from $7.7 billion to $9 billion during his four years in office. Assuming that the city workforce falls a bit this year, as de Blasio has promised, Gotham will pay each of its workers an average of $98,604 this year (not including benefits), up from $83,617 in 2014.

De Blasio offers two rejoinders to critics. He notes, first, that Bloomberg refused to sign contracts with unions after the 2008 economic crisis unless their members agreed to retirement-benefit cutbacks and productivity efficiencies that generated enough savings to pay for any raises, so he had to make up for this pay freeze when he came to office. But this argument doesn’t hold up. When Bloomberg said that New York couldn’t afford raises, he was correct. In fact, de Blasio hasn’t been able to afford them. During his first year in office, he delayed a total of $5.2 billion in payments for retroactive raises to this year, when taxpayers will have to pay $842 million to city employees for work done as far back as 2008. They’ll have to come up with similar payments for the next three years, when the final $1.5 billion payment is due. De Blasio also argues that much of the cost of the raises he awarded is offset by health-care savings. But though health-care costs for city workers and retirees are slowing in growth, they’re still growing. Fringe benefits, mostly made up of health-care benefits, will amount to $10.1 billion this year, up from $8.1 billion in 2014.

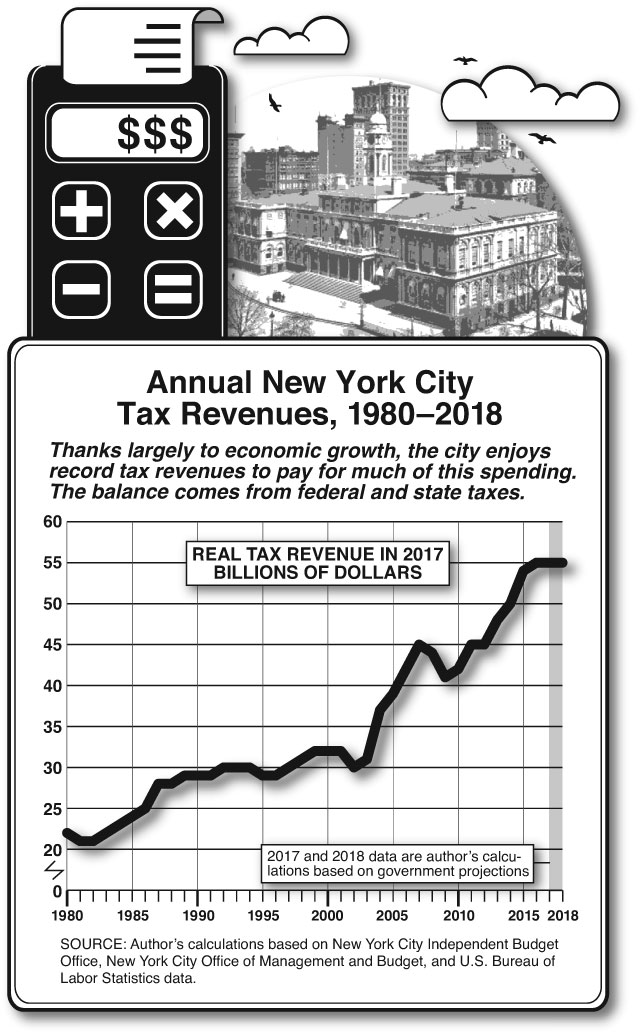

De Blasio has been able to pay for this largesse for one simple reason: compared with many other parts of the country, New York has enjoyed a powerhouse economy. The city recovered the jobs lost during the 2008 recession nearly a half-decade before the nation as a whole did. Gotham now has 21 percent more jobs than it did in 2006, near the end of the previous economic boom. As de Blasio enjoys saying, in just two years, New York City gained more jobs than 11 states combined, including reasonably healthy states like North Carolina, Tennessee, and Massachusetts. And though Wall Street has earned record profits since 2008, it hasn’t powered local job growth, which has been impressively diverse. From construction to tech, from manufacturing to tourism, New York’s economy has surged.

Tax revenues have poured in. In 2014, New York City collected $49.9 billion in tax revenues, and this year, it expects to collect $56.5 billion. The city receives the balance of its funding from federal and state sources, but it is this $6.6 billion increase in local revenue that has allowed de Blasio to ramp up its spending. Like most cities, New York relies on a property tax as its primary source of revenue; unlike most cities, Gotham has seen property taxes recover strongly, and then some, since the Great Recession. In 2014, New York collected $20.6 billion from these taxes, about $5 billion less than the $25.6 it will take in this year, thanks largely to higher commercial real-estate values. Similarly, as the rest of the country has struggled with slowing retail sales, New York has done fine; our record 60.3 million tourists, double the number of little more than a decade ago, have made up for any slump in local working-class or middle-class spending. The city expects to collect $7.4 billion in sales taxes this year, up from $6.7 billion when de Blasio took office.

But though people of all incomes want to live in or visit New York, the people who make the most money are responsible for an ever-larger portion of our tax collections. Despite the city’s progress in cultivating job growth away from Wall Street, New Yorkers collectively still earn 19.1 percent of their wage income each year from the securities industry. And other top earners have done well in recent years in the city. As equality-obsessed de Blasio has often noted in his budget presentations, New York’s top 10 percent—families earning more than $369,000 annually—have enjoyed the bulk of wage gains during the recovery, watching their incomes go up by 10.9 percent, compared with the 4.1 percent seen by New York’s middle class. This year, New York expects to collect $11.7 billion in income taxes, up from $9.8 billion in 2014. About half of that money will come from top earners: in 2014, the last year for which data are available, New York’s top 1 percent of tax filers—37,273 households—paid 49.3 percent of the city’s income taxes, according to the city’s independent budget office.

Back in the 2013 campaign, de Blasio proposed a “millionaires’ tax”—a higher tax rate on people earning $500,000 or more annually—to raise $530 million for his prekindergarten expansion. Albany, which controls most New York City taxes, shot down this idea, but as it turned out, the mayor never needed the money. Economic growth, particularly at the top, has enabled de Blasio to collect more than three times the extra money that he expected to reap by boosting the income-tax rate for top earners. Despite de Blasio’s rhetoric on inequality, then, the mayor actually depends on inequality to fund his budget.

Though it doesn’t seem so to the parts of the country that made Donald Trump president, it’s been nearly a decade since the last recession. With America’s private-sector debt reaching disturbingly high levels again, the country has a fair chance of facing another recession, and soon. New York may be seeing early signs of trouble: the city recently had to revise what it expects to collect in taxes, lowering it by $567 million for this year. Private-sector job growth has slowed, to 2.3 percent this year, down from 3.4 percent last year.

In the short term, New York’s risks from a recession are the same as they’ve been for more than half a century. The city would experience a sudden decline in tax revenues as wealthier residents, in particular, see losses on investment income and their annual bonuses dwindle or disappear. From 2007 to 2008, for example, New York endured an immediate $2.7 billion drop in tax revenues, and the city did not recover its annual resources for nearly three years. Though de Blasio points to the city’s $1.7 billion in reserves as evidence of his fiscal responsibility, even a mild recession would swallow that amount within a few months—and reveal the city’s vulnerabilities.

“Even with record tax revenues, New York isn’t putting aside the money that it needs to keep up with its economic growth.”

Chief among those vulnerabilities is New York’s failure—over two economic booms and two mayoral administrations of supposedly different ideological bent—to come to grips with its unaffordable promises to its public employees. Even in the midst of, or perhaps at the end of, economic good times, these liabilities are sobering. As of 2016, New York had underfunded its public-pension plans by $64.8 billion. New York’s pension funds—the money that it needs to pay benefits to more than half a million current or future recipients—are just 65.6 percent funded, on average. That’s a good ratio compared with, say, cratering Chicago, but bad when one considers the extraordinary resources that the city enjoys. The $9.6 billion that New York now deposits into its pension funds yearly is not enough to make up for this deficit. In 2016, the city’s pension funds paid benefits to retirees and survivors totaling $14.1 billion, more money than it had put in. This persistent imbalance makes it impossible to build up sufficient assets for the future. New York has underfunded its health-care promises to future retirees by $89.4 billion, having put just $4.2 billion aside for this purpose.

Despite these looming liabilities, New York hasn’t taken simple steps toward paring them down. On pensions, E. J. McMahon of the Empire Center has suggested that the city put aside the money that it’s saving for future, as opposed to existing, wage increases. This would improve the pension funds’ shortfall by nearly $700 million this year and $1.6 billion next year. But the city so far has not made such a move, nor have any candidates for mayor taken up the idea. Retiree health-care costs are a second problem. Almost all private-sector retirees pay their own Medicare premiums out of Social Security or other cash income. But despite guaranteeing its own retirees income of at least half their final salary, including overtime, for life, New York continues to pay their Medicare premiums as well.

New York faces yet another major liability: its infrastructure deficit. Even with record tax revenues, New York isn’t putting aside the money that it needs to keep up with its economic growth and the strain that that growth creates on schools, bridges, and parks. The mayor has proposed $95.8 billion in infrastructure spending over the next decade. But the priorities are skewed: $10.9 billion would go to housing, for example, even though the building of subsidized housing for a comparative lucky few isn’t public infrastructure. Meanwhile, the city’s contribution to the state-run subway system remains paltry: only $2.5 billion over five years, not nearly enough to launch the next phase of the Second Avenue subway or upgrade signal systems to allow for more trains.

Worse, de Blasio depends almost entirely on debt to fund this capital program: $88.9 billion in new bonding. Even with interest rates close to record lows, this borrowing will send annual debt costs skyrocketing, from $6.5 billion today to $8.4 billion three years from now. Consider: this one ten-year capital program would more than double New York’s $83.4 billion in total debt outstanding—debt it took four decades to amass.

There is no doubt that New York, over more than 20 years, has been both smart and lucky: smart in cutting crime and improving the quality of life to attract a record number of residents, tourists, and investors; and lucky in that the global economy, for better or worse for the rest of America, has favored the urban elite in finance, tech, and other high-paying industries. Successive mayors have been able to ignore warnings over the past two decades about fiscal profligacy. New York would be even luckier if these trends never changed—but they could. And if they do, New York may wish that it had spent its boom years building for a sturdier future.

Research for this article was supported by the Brunie Fund for New York Journalism.

Photo by Pool/Getty Images