Donald Trump’s surprise election win dramatizes how weak the party system in the United States has become. Over the course of the twentieth century, the Republican and Democratic Parties gradually lost control over the electoral process that they once dominated. Though party affiliation still runs fairly strong among voters, party organizations are much weaker than they used to be, especially with respect to presidential campaigns. Party leaders once selected candidates and promoted them to the electorate; now, the candidates themselves, independent groups, and the media largely handle these functions, with party organizations playing only a supporting role.

The decline of the party system offers one of the most potent examples of the unintended consequences of good-government reforms. Starting in the early twentieth century, Progressive reformers weakened parties in an attempt to make American politics more democratic. The result has been a weaker democracy overall.

The Framers had a complicated relationship with political parties. Concerned about the threat that “factionalism” posed to free government, they designed the Constitution to prevent any group that purported to represent a “part” of the nation from dominating the whole. As James Madison explains in Federalist 10, it is inevitable, in a free country, that factions will form. But separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism, as well as the new nation’s sheer size, would keep majority and minority parties from bringing down the republic.

And yet the Framers’ own political activities were premised on the assumption that, in public life, it is often necessary to band together with allies to pursue shared goals, punish enemies, and reward friends. Jefferson and Madison were particularly active partisans in the years after the Founding. Their “Democratic-Republican” Party sought to block Federalist Alexander Hamilton’s program of a stronger and more centralized government. Jefferson and Madison set up newspapers, recruited like-minded candidates to run for Congress, and coordinated efforts to defeat the reelection bids of legislators who didn’t share their political views. Jefferson and Madison saw their efforts as “a party to end parties”—and they succeeded. Hamilton’s Federalists declined and disbanded, and Democratic-Republicans won every presidential election through 1820.

The quasi-constitutional arrangement that political scientists would term “the party system” did not emerge until the 1830s. Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson were its founding fathers. Van Buren, a senator from New York when he began promoting the idea of a two-party system, believed that the Constitution’s presidential-selection process was flawed. His fears were galvanized by the election of 1824. Parties played no role in the selection process that year, and, as a consequence, none of the four major candidates won a majority in the Electoral College. As required by the Constitution, the decision moved to the House of Representatives, which gave the victory to John Quincy Adams, though Andrew Jackson had won the greater plurality of votes. Van Buren believed that a president who had not won an Electoral College majority and owed his position to Congress would lack legitimacy.

Though many saw Jackson, with his military background and immense popularity, as a Napoleon in the making, Van Buren viewed the former general as the solution to the potential crisis of legitimacy. He resurrected the Democratic-Republican apparatus and offered its support to Jackson in exchange for his agreement to submit to party discipline. Jackson defeated Adams decisively in 1828. The first national major-party convention was held in 1832, at which Jackson was nominated for a second term, with Van Buren as his vice president and anointed successor. Van Buren’s activities—both as a Democratic partisan and an exponent of a party system—pressured the anti-Jackson camp to form a short-lived counterparty, the Whigs, whose members would later form the core of the modern Republican Party.

Van Buren also promoted the party system’s ability to structure and moderate political conflict. He wanted parties to be national in scope, in part to restrain sectionalism, one of the greatest sources of division in early-nineteenth-century America. At the same time, American politics remained highly decentralized through the nineteenth century, a trait reflected in, and perhaps even reinforced by, the party system. Leadership was concentrated in state capitals and city halls. The proverbial “smoke-filled rooms,” in which presidential nominees were chosen every four years, were occupied by heads of state and local party organizations. Swelling big-city populations after the Civil War forced party power down to the local level by increasing the number of votes that urban “bosses” commanded. Local leaders became kingmakers at presidential nominating conventions.

The local parties, in turn, depended heavily on patronage. As Charles Croker of Tammany Hall once casually explained, “Now since there must be [city] officials, and since these officials must be paid, and well paid, in order to insure able and constant service, why should they not be selected from the membership of the society that organizes the victories of the dominant party? In my opinion, to ask this question is to answer it.” Historians make much of the material incentives that attracted many poor city dwellers to parties: the hods of coal and chickens at Christmas and free entertainment. “Big Tim” Sullivan, another Tammany functionary, was a part owner of Dreamland on Coney Island and reportedly hosted 15,000 people at his annual Labor Day “chowders.” In an age with practically no government-sponsored safety net, the parties often served as informal social-services organizations for their overwhelmingly poor constituents.

In addition to these material benefits, what James Q. Wilson termed “solidary rewards” were another key source of party strength. The bonds of loyalty and friendship forged by parties moderated the profound societal changes inevitable in an industrializing and urbanizing nation. Parties now prize ideological commitment; back then, the party man’s characteristic virtue was loyalty. It was well illustrated by Vice President Harry Truman’s willingness to attend the funeral of Tom Pendergast, the former Kansas City political boss whose career had ended with a tax-evasion conviction. Pendergast mentored Truman, and the association with machine politics dogged the future president throughout his rise in national politics. Truman faced considerable risk to his reputation in attending the funeral—but he went anyway. Biographer David McCullough sets the scene: “[Truman] was photographed coming and going and paying his respects to the family, all of which struck large numbers of people everywhere as outrageous behavior for a Vice President—to be seen honoring the memory of a convicted criminal. Yet many, possibly a larger number, saw something admirable and courageous in a man risen so high who still knew who he was and refused to forget a friend.” Truman was just one of many poor strivers who would never have gained political prominence if not for old-fashioned party politics. Another was Al Smith, the greatest governor in New York’s history. Parties substantially aided America’s rapid assimilation of millions of immigrants, too.

For many good-government reformers, however, the parties’ dependence on patronage, which in practice can be hard to distinguish from loyalty, was a deal-breaker. Public corruption in America was never as rife as during the golden age of the party system, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It came in every variety: election-rigging, kickbacks on government contracts, using inside knowledge about planned transit routes to speculate in real estate (“honest” graft), collecting protection money from organized crime and vice interests (“dirty” or “police” graft). Revelations produced by high-profile trials such as William Marcy “Boss” Tweed’s in 1871, the investigative journalism of Lincoln Steffens, and the flagrancy of the machines’ misdeeds indissolubly linked party politics and corruption in the public mind.

Progressive reformers’ objections to the traditional party system were not limited to its corruption. At a deeper level, they viewed it as undemocratic. Frequently, the “boss” was not an officeholder, and the elected mayor, governor, and legislators were ciphers. Accountability to party organizations, as opposed to voters, was no accountability at all, in the view of the Progressives. The party system also enabled government by amateurs. The Progressives promoted an aggressive expansion in government’s responsibilities that could be properly implemented only by administrators appointed based on expertise, not political allegiance.

No one articulated the Progressive vision for parties more clearly than Woodrow Wilson. Whereas Van Buren saw parties as a restraint on politicians, Wilson argued for placing parties in the service of great leaders and their agendas. Parties should be committed to distinct programs, which, in turn, should be articulated by visionary politicians, whose services were becoming more needed in an increasingly complex world. The true party leader, Wilson wrote, would be the president, who, through his rhetoric, would give purpose to the party organization: “He can dominate his party by being spokesman for the real sentiment and purpose of the country, by giving direction to opinion, by giving the country at once the information and the statements of policy which will enable it to form its judgments alike of parties and of men.” As president, Wilson reinstated the custom of appearing before Congress to deliver the State of the Union address.

Some Progressive reformers wanted to go even further and eliminate parties altogether or sharply circumscribe their responsibilities. They pushed for reforms, including nonpartisan elections, council-manager government, recalls, referenda, and, at the federal level, direct election of senators. Civil-service protections placed limits on patronage opportunities.

But the most important Progressive change was the direct primary system. Advocates of primaries reasoned that politicians with a close connection to the electorate would be less beholden to party organizations. Parties are strong, in an institutional sense, to the extent that individual candidates and officeholders are weak. Thus, the Progressive party system would facilitate a more democratic political order—because candidates would base their support on popular votes in primaries, not on the blessing of backroom bosses.

The Progressive reform agenda decisively weakened parties, though the effects would take years to make themselves felt. States began adopting primaries around World War I, though a “mixed” nominating system of appointed delegates and popular votes prevailed throughout much of the twentieth century. In 1968, Hubert Humphrey became the last presidential candidate to win a major party nomination without competing in a direct primary. In the wake of his defeat that year by Richard Nixon, the Democrats adopted rules changes that assured that the nomination went to the winner of the most votes in primaries (and caucuses). Their reformist impulses sharpened by Watergate, Republicans eventually followed suit. Candidates’ acceptance speeches soon superseded party platforms in defining what elections were about.

Other changes in American society and political life weakened parties. The growth of entitlement programs during the New Deal and Great Society devalued the comparably scanty material benefits that the parties provided. Political scientist Edward Banfield argued that parties were doomed by the weakening of partisan loyalties among the general populace:

The ruling elite always favored—in principle if not in practice—a politics that would settle issues on their merits rather than “give everyone something.” . . . The nonpartisan style of the elite steadily diffused into the middle class. As incomes increased and more and more boys and girls went to high school and even to college, the size of the middle class grew both absolutely and in relation to the working class. All those who had read a civics book knew that “bosses” were always “corrupt” and that the enlightened citizen would vote for “the best man regardless of party.”

Media and money also dealt devastating blows. As modern technology developed means of communicating directly to a mass audience, especially via television, candidates no longer needed parties’ help in reaching voters. In their heyday, parties served as vital mediating institutions between candidates and voters. Today, the mass media perform this function. In the old days, party leaders played the critical role in determining who should be considered a legitimate candidate for office. In recent decades, journalists and newspaper columnists have acquired significant, if not decisive, influence over these determinations—at least until the arrival of Trump. It remains to be seen whether Trump’s ascension represents the demise of media “vetting” of candidates or whether his example will prove to be sui generis.

As the role of media has increased, spending on campaigns has risen. More important than the absolute cost, which alone did not doom parties to obscurity, was how campaign-finance reform, as well as the First Amendment jurisprudence aimed at rolling it back, weakened parties. The 2002 McCain-Feingold Act placed significant restrictions on parties’ fund-raising activities that the 2010 Citizens United decision and related rulings did not repeal, even while they greenlighted super PACs and other independent groups. Some also argue that independent groups have secured an outsize share of talented political operatives, to the detriment of party organizations. If it’s a zero-sum game between parties and individual candidates, the current landscape favors the candidates. Parties may receive much larger contributions, but super PACs and other outside groups target their support directly to candidates.

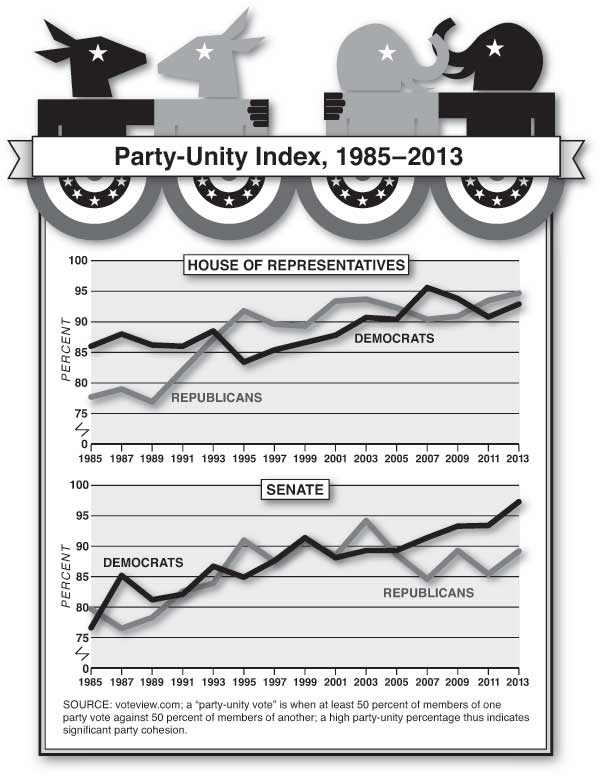

The Democratic and Republican Parties remain essential to the functioning of American politics. It’s still extremely rare for politicians to switch parties. At both the state and national levels, legislatures could not function without their partisan structures. The only practical way for an incoming presidential administration to fill the thousands of political appointments it needs to make is to rely heavily on its party network. Party labels still play an important “signaling” role to voters. For even the most informed voter, it usually makes more sense to vote for the party, not the candidate, since there’s no stronger predictor about what politicians will do in office than party affiliation. Both parties have become quite effective at signaling, because they are much more closely tied to particular agendas—just as Wilson had intended. Liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats are much harder to find than they were in 1970. The “party-unity index,” which measures the share of members voting based on party lines, has grown significantly in recent decades (see chart below). More and more, culturally conservative areas in the United States have drifted toward the Republican Party and liberal areas toward the Democratic Party. The two parties have become thus more principled: politicians and voters are bound more by shared values than bonds of loyalty or patronage.

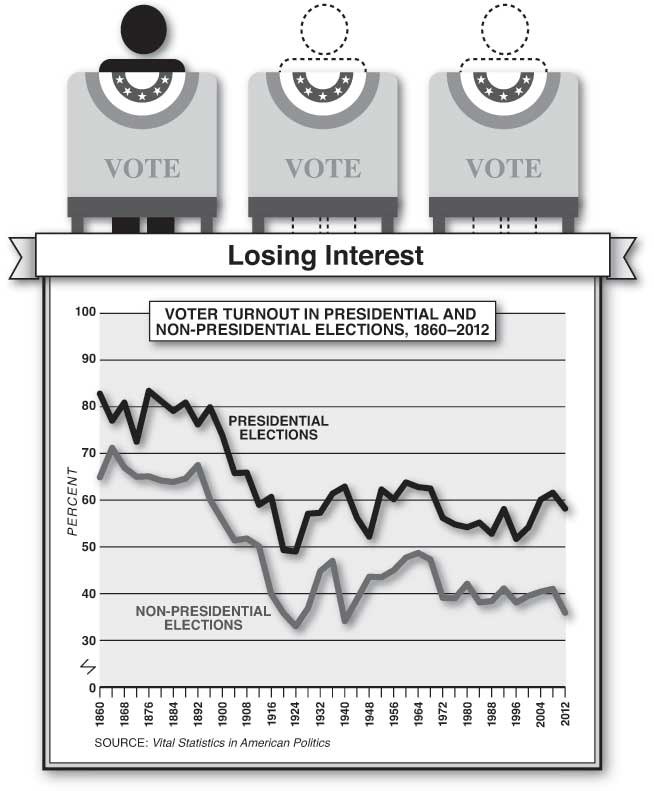

But though the Progressive dream of a more “responsible” party system has been largely realized, it has failed to produce a healthier democracy. Voter turnout has declined (see chart below). Good-government types often claim that corruption discourages political participation, but the historical evidence suggests the opposite. Voter-turnout rates peaked during the age of boodle. The apocalyptic character of modern political rhetoric stems from the parties’ greater ideological consistency. Every election is deemed “historic,” with Republicans promising to take the country in a markedly more conservative direction and Democrats a markedly more liberal direction. These fears were less pronounced in the days of Rockefeller Republicans and the Solid South. Political messianism has delegitimized the notion of a loyal opposition. Weakened parties have thus engendered cynicism toward other institutions. During the Obama years, liberals reflexively described Republican legislators’ opposition to the president’s policies as “dysfunction” and “obstruction” and believed that it justified the administration’s many constitutionally dubious aggrandizements of executive power.

Wilson hoped that, as candidates gained at the expense of party organizations, the quality of political leadership would improve. It would be hard to argue that this has happened. In terms of public opinion, lower levels of voter turnout surely reflect broad dissatisfaction with candidates. In 1956, Gallup began compiling preelection “favorability” scores. In the most recent survey, done just before the 2016 election, Trump received the highest “unfavorable” score in the poll’s history and Hillary Clinton the second-highest.

The ever-increasing length of the primary season has cut deeply into the time that officeholders up for reelection may spend on governing as opposed to campaigning. Zealots dominate the electorate in low-turnout primaries, which prompts candidates to adopt extreme positions that will be impractical to implement. Decades ago, James Ceaser, the leading expert on the origins of the modern party system, warned that the “openness” of the primary system has “contribut[ed] to a decline of the Senate as a serious deliberative body.” The media-centric styles of, say, Senators Charles Schumer and Ted Cruz demonstrate Ceaser’s foresight. And though Trump’s victory, despite his being outspent two to one, has temporarily put to rest overheated rhetoric about how “money buys elections,” the fund-raising responsibilities of the modern candidate are momentous and hardly conducive to the work of governing.

With the tensions among its various constituencies, the Democratic Party almost certainly faces a reckoning about its future direction. (See “Children of the Revolution,” Autumn 2016.) But Democrats retain more vestigial traces of the old party structures than the Republicans. The recent WikiLeaks revelations confirmed not only that party operatives had a distinct preference for Hillary Clinton; the operatives also actively promoted her candidacy, even amid the supposedly “open” primary process. As the candidate who was both more moderate and corrupt, Clinton fit the role of the quintessential party nominee. But she arguably deserved the nomination, being the candidate most loyal to the Democratic Party. Bernie Sanders may be a more principled liberal than Clinton; but throughout his decades in Congress, he identified as an Independent.

Unlike Republicans, Democrats have super-delegates—elected and party officials free to vote for a nominee, regardless of how much of the popular primary vote he or she wins. Under current rules, super-delegates represent 15 percent of the Democratic delegate count, but they have never attempted to override the popular primary vote, and it is doubtful that they ever would. Originally, America’s political parties were private associations regulated and run by party members in good standing. Now, however, they function as “public utilities,” in the words of Ceaser. It’s easy to imagine how super-delegates could assert themselves in a private-association-type scenario, but less so when the party is a public utility whose advantages almost anyone can claim access to.

Notwithstanding its recent, stunning success on Election Day—the presidency, the House, the Senate, and a net gain of two governorships—the Republican Party’s long-term problems may be greater than Democrats’. The GOP is now in the unusual condition of having a leader, President Trump, whose success was premised on discord within the party. Trump won only a plurality of the primary vote—46 percent, a lower share than Mitt Romney (53 percent), John McCain (47 percent), and George W. Bush (62 percent). Republican opposition to Trump was hopelessly diffused amid 16 other candidates vying for the nomination, none of whom differed substantially on the issues. Trump, who has switched his registration several times during his lifetime, has a strictly utilitarian view of party. It’s not clear whether Republicans, over the long term, will be able to rally behind a Trump agenda. The modern GOP thus faces an uncertain future, since neither the Wilsonian model of an organization united behind a program, nor the Van Buren model, in which leaders are subordinate to the organization as a whole, seems to apply in Trump’s case.

“The dream of a more ‘responsible’ party system has been realized, but it has failed to produce a healthier democracy.”

The attack on “establishment” Republicans that helped fuel Trump’s bid presupposed that such a group existed and was strong enough to impose its views on unwilling party members. In reality, a true party establishment hasn’t existed for decades, and it is difficult to see a way back for the traditional party system. The parties thrived in a more decentralized political environment, and American government is now highly centralized. For lack of a definitive road map back to the days before super PACs and direct primaries, the following recommendations sketch out what a more party-centric political system would look like.

First, parties should have more power over campaign finance. Free-speech advocates celebrate the wide-open, post–Citizens United landscape, but it has come at a cost: outside groups promote a more ideological style of politics than parties, and they’re less transparent. Political scientist Raymond La Raja has argued for raising contribution limits to parties and giving parties more flexibility to spend on behalf of individual candidates.

Second, states should be wary of institutionalizing their current lack of party competition. California recently instituted a “top-two” system for statewide offices, the state legislature, and the U.S. Senate and U.S. Congress. In races for these positions, candidates now compete in one primary, open to all, and the leading two vote-getters—both Democrats in the 2016 U.S. Senate race—then compete in the general election. Republicans shouldn’t be the only ones concerned about the dangers inherent in such a system. Throughout American history, at the state and national levels, both parties have gone through long stretches in a state of seemingly permanent opposition, only to rebound later. It is particularly important, at a time in which one-party rule is on the rise, that politicians acknowledge the importance of organized opposition.

Third, some form of spoils should be tolerated. The Brookings Institution’s Jonathan Rauch has argued that Congress would become naturally more effective were it to repeal the earmark ban in place since 2011—though this would enrage good-government reformers. Stronger parties need strong party leaders who can discipline their members, and this will sometimes require inducements of a material nature.

Fourth, politicians should exercise more forbearance over indulging voters’ preference for “outsiders.” The lack of political experience should not be an automatic qualification for high office. Almost by definition, leaders of party organizations are members of an “establishment.” Unless we find some way to empower them, our political future is likely to be even more chaotic than at present.

Photo: Martin Van Buren helped found America’s modern party system. (GRANGER, NYC — ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)