Basketball superstar Lebron James takes pains to make it clear: “I just always want you guys to remember that I’m just a kid from Akron, Ohio.” As James’s frequent encomiums to his hometown make clear, this Rust Belt city of just under 200,000 people (in a region of 700,000) still boasts a fierce civic spirit. But Akron and its most famous son don’t compete at the same level. “King James” is an international basketball superstar, an all-time great of his sport. Akron is a quintessential middle city, more like a role player or sixth man off the bench. It’s not a big city, like Cleveland, or a small one, like Lima, Ohio. It’s neither an economic nor a demographic superstar. Like many other industrial cities, such as Flint or Youngstown, it declined significantly starting in the late 1960s, but less severely than many others. Akron is still characterized by middle- and working-class neighborhoods, in a country where the middle class has been getting squeezed. It’s not a sexy city, full of glitzy projects to wow the outsider, but its many low-key quirks give it a unique personality.

America has lots of postindustrial middle cities trying to reinvent themselves for a new century. Akron is one of the better-positioned, and its eventual fate may give us a hint about the prospects for others.

Unlike many early industrial centers, Akron did not develop along a major river, ocean, or lake. Rather, it was an artificial waterway, the Ohio and Erie Canal, that made the city’s growth possible when it opened to Akron in 1827. Akron struggled with, but ultimately adapted to, the railroad era. Industries took root, including milling and the manufacture of clay pipe and matches.

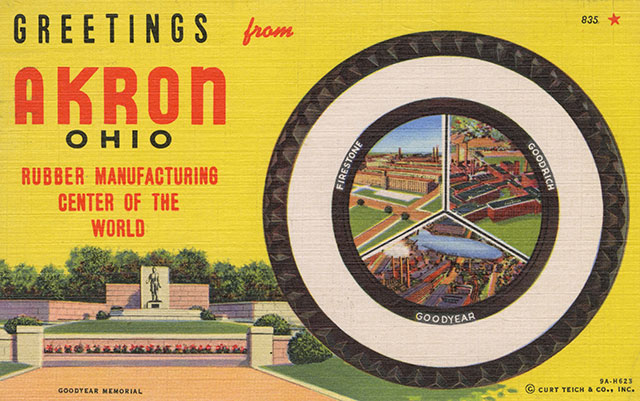

But ultimately, it was the rubber industry that propelled Akron, still known today as the Rubber City. BF Goodrich set up shop in 1870, and others followed. Goodyear was founded in 1898 and Firestone in 1900. General Tire launched operations during World War I.

During the booms and busts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many industrial businesses consolidated into national giants. Out-of-town concerns acquired many local businesses in Akron, too. The city’s milling industry, for example, got rolled up into Chicago-based Quaker Oats. But the rubber industry consolidated into Akron instead of away from it. Business surged there as the rise of the automobile fueled demand for tires. Prior to World War II, Akron’s big four producers made about 80 percent of all the tires in the U.S., and the war brought another spike in demand. Akron was the world’s rubber capital, and the rubber business literally seeped into the pores of Akron citizens: workers’ hands would become so stained with carbon black that it would take six months after leaving a job before the color leached out of their skin.

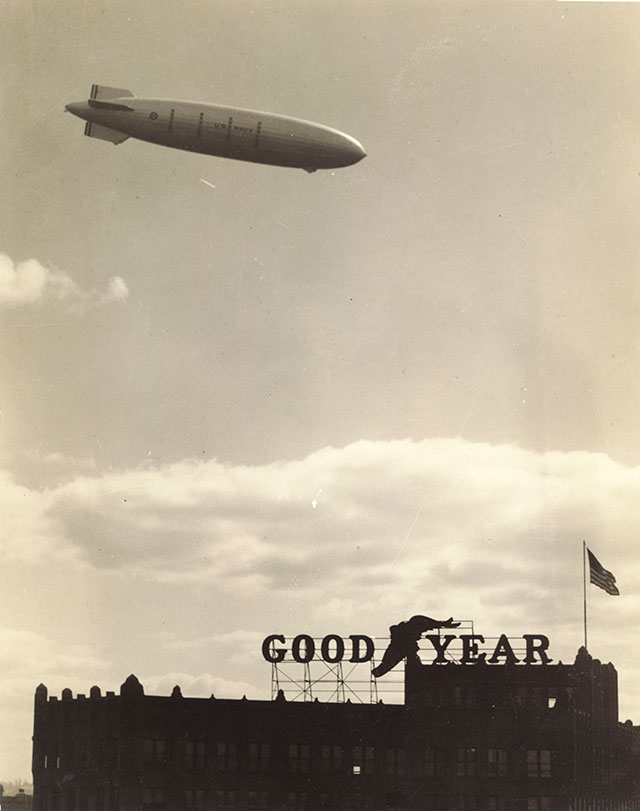

During America’s industrial heyday, Akron rubber companies rode high. Goodyear expanded into the airship business, which continues into the modern era in the form of the iconic Goodyear Blimp. The gigantic black Goodyear Airdock, still an Akron landmark, was long the home of the firm’s airship and defense operations. Akron flourished in the postwar era, too, reaching its municipal-population peak in 1960.

Like many other industrial regions, however, Akron hit choppy waters in the 1970s. As with autos, part of the story was foreign competition. In this case, it wasn’t low-cost, high-quality Japanese cars but technical innovations from a European competitor. The French tire company Michelin had developed the radial tire, far superior to the older bias designs that Akron firms were still using. In 1968, Consumer Reports gave its seal of approval to radials, finding that they had longer life, steered better, and delivered superior gas mileage than tires using the dominant bias designs.

Akron’s major firms also faced labor strife—and not for the first time. The Akron rubber industry was the scene of the first large-scale use of the sit-down strike in 1936. Unions went on strike for three months in 1967, and they struck Goodyear in 1970, the same year that Ford became the first U.S. automaker to include radial tires as a standard feature on one of its models. The unions struck again, for four and a half months, in 1976, long after it had become obvious that radial tires represented an existential threat to Akron’s legacy producers.

The radial tire soon conquered the world. Akron rubber firms proved fatally slow to adapt and found themselves swallowed by foreign competitors. General Tire was bought by Continental, a German company; Firestone was bought out by Japanese Bridgestone. BF Goodrich merged into Uniroyal before being acquired by Michelin. Only Goodyear, which made a major investment in 1974 to retool for radials, survived as a major tire manufacturer based in Akron, though it had to sell off its most profitable divisions and take on significant debt to fend off a hostile British takeover attempt in 1986.

Employment had been declining at Akron’s rubber companies before foreign absorption because the firms had built more modern and efficient factories outside the city, often in the less union-friendly South. As productivity grew, demand for workers fell. Downsizing, plant closures, and mergers devastated rubber-industry employment. The industry employed 37,100 people in 1964. By 1984, that number was down to 15,400; by the 1990s, it had cratered to 5,000. Economist George Knepper estimated that Akron lost 35,000 manufacturing jobs between 1970 and 1990.

As elsewhere, this was not just a matter of economic statistics but also of the wreckage of lives and a strike at the heart of a community. “In 1977, I could smell rubber in the air, and many of my family members and friends’ parents worked in rubber factories,” local urban planner Jason Segedy wrote. “In 1982, the last passenger tire was built in Akron. By 1984, 90 percent of those jobs were gone, many of those people had moved out of town, and the whole thing was already a fading memory. Just as when a person dies, many people reacted with a mixture of silence, embarrassment, and denial. . . . When the mythology of your hometown no longer stands up to scrutiny, it can be jarring and disorienting. It can even be heartbreaking.”

“Even in the troubled 2000s, when every Ohio metro area lost jobs, Akron was down only 4 percent.”

Akron, then, is clearly a Rust Belt city —though it’s healthier than most. Metro Akron’s population, for example, has actually expanded since 2000, albeit slightly. That makes it one of only three Ohio metros to post growth in that period. Its municipal population has fallen by a steep 31.9 percent since its peak in 1960, but other urban centers in Northeast Ohio have fared worse. Canton is down 39 percent, Cleveland 57.8 percent, and Youngstown 62.2 percent. On the jobs front, Akron is the third-best-performing metro area in Ohio since 1990. Even in the troubled 2000s, when every Ohio metro area lost jobs, Akron was down only 4 percent, again third-best in the state.

Akron’s postindustrial nature becomes obvious when driving around it, but the city is basically intact and functional, though scarred with the same drug scourge plaguing many other areas. It has its share of abandoned buildings, but Akron is not the first place that one would go to take pictures of “ruin porn.” It never suffered the kinds of blows that, say, Flint or Youngstown did. Those cities were branch-plant towns for industries based elsewhere; by contrast, Akron had its own industry, rubber, making it a headquarters town, not a satellite. Though it has moved all tire production other than specialty racing tires elsewhere, Goodyear remains based in Akron, and recently built a $160 million headquarters in the city, housing many white-collar and R&D jobs.

One legacy of being a headquarters city is that Akron retained significant R&D know-how around polymers (rubber is a type of polymer). This helped the economy diversify away from purely rubber into polymers generally, and the city eagerly touts itself as a polymer capital. Today, 200 firms working with polymers in greater Akron collectively employ 10,000 people. The University of Akron has focused heavily on polymer research and has won numerous patents for its polymer discoveries, many with applications outside the tire business. One new polymer material developed there improved coronary stents that were implanted in 6 million patients, according to the Akron Beacon Journal. The University of Akron pocketed $5 million for it. The polymer cluster hasn’t replaced the economic engine of the rubber industry, but it’s more than many other postindustrial cities have managed to create.

Because of its relative performance economically and demographically, as well as its polymer-capital reinvention, Akron was widely seen as successful in navigating the transition to the postindustrial economy. In 2008, the Brookings Institution published a “Restoring Prosperity Case Study” on the city.

In recent years, though, Akron’s performance has raised questions. In a 2016 study, the Greater Ohio Policy Center (GOPC) suggested that “Akron’s comparatively strong reputation may no longer align with the situation on the ground.” This study, which focused on the city proper, rather than the region, revealed a slow erosion of Akron’s performance relative to peer cities like Erie, Pennsylvania; Fort Wayne, Indiana; and Worcester, Massachusetts. Akron’s per-capita income declined nearly twice as much as in peer cities, its poverty-rate increase of 10 percentage points was higher than in most of those cities, and its employment trends were worse. Among the other challenges flagged by GOPC was the city’s aging housing stock, with 75 percent built prior to 1970 and 35 percent being more than 75 years old. And like many American cities, Akron has also seen a recent uptick in murders. According to the Akron Beacon Journal, the city had 42 homicides in 2017, up from 32 in 2016.

A cloud also hangs over the University of Akron. The school saw a significant enrollment decline in the wake of the short tenure of controversial president Scott Scarborough, who laid off more than 200 university employees while spending nearly $1 million on renovations to the president’s residence, which included such items as a $556 olive jar. The faculty senate overwhelmingly passed a vote of no confidence in his leadership. The university is one of the city’s critical institutions, and its struggles come at an adverse time, with projections of a declining number of high school graduates in Ohio and a drop in international student visa applications.

Akron is also adjusting to a political transition. After 28 years in office, Democrat Don Plusquellic unexpectedly resigned as mayor in 2015, citing unfair coverage from the Akron Beacon Journal, in particular its reference to him as a “bastard” in an editorial. His successor lasted eight days in office before resigning over inappropriate conduct toward a female city employee. The city council president then served as caretaker mayor until Dan Horrigan, also a Democrat, took office in 2016.

Horrigan appointed a blue-ribbon commission to examine city operations. It, too, highlighted demographic challenges—notably, the city’s low percentage of adults with college degrees: just 20.1 percent, worse than all but one of 14 peer cities studied. As a metro area, Akron is doing better on this measure, at 31 percent, third-highest among Ohio metros and higher than metro Cleveland. The disparity suggests a disconnect between city and suburban performance—a familiar symptom of postindustrial cities.

Combating weak demographics is one of Horrigan’s key agenda items. He wants to reverse population loss and start growing the city again, using tools like generous tax abatements on housing upgrades. His goal is to attract 50,000 new residents to Akron by 2050.

One unlikely source of new residents has already started making a difference: fleeing from Bhutan, ethnic Nepali refugees were resettled in Akron, and the city is now home to one of the largest Nepali communities in the U.S., with about 5,000 residents. The Nepalis are centered in the North Hill neighborhood, which boasts the kinds of ethnic grocery stores and restaurants that one would expect of an immigrant neighborhood. Local leaders have rolled out the welcome mat, eager for new blood in a region with a low share of foreign-born population. The Nepalis have integrated well so far, many becoming home and business owners, but for now, they remain concentrated at the lower end of the economic spectrum.

Akron’s downtown is seeing some flow of new residents—many of them university students. Private developers have constructed about 2,000 units of student-oriented housing. The nonstudent market has grown more slowly, in part because of a lack of supply. Downtown apartment occupancy has reached nearly 100 percent as amenities have improved, with top-quality coffee and microbrews now on offer. The city has focused on upgrading its downtown, with improvements to Main Street and along the Ohio and Erie Canal, where a recreational trail has been added.

Despite these green shoots, the city’s population has been treading water. Considering that the entire Akron metro area has added only 6,300 new residents since 2000, and that the rest of Northeast Ohio is shrinking, growing the population by 50,000 looks like an ambitious and possibly unrealistic goal. Accomplishing it would require a major demographic turnaround or poaching a large number of residents from elsewhere in the region, an unlikely prospect.

Akron is also seeking to build itself up as an innovation hub for the region, creating an entity called Bounce, which shares a building downtown with the Akron Global Business Accelerator. Akron already had the Launch League, a community network that hosts an annual startup conference called Flight and offers co-working spaces and other business amenities. These efforts, standard types of startup community-building efforts, are nascent. The technology industry remains heavily concentrated in Silicon Valley and in other coastal cities such as New York and Boston. Even the best midwestern technology communities, outside of Chicago, are fairly small. Akron would not appear to be well positioned to be a major startup hub—but any activity will help. RVshare, a company dual-headquartered in Akron and Austin that does exactly what its name implies, recently raised $50 million in funding, though how much will be invested in Akron is unclear. Robert Hohman, CEO of the Silicon Valley firm Glassdoor, which allows employees to post reviews of working for particular companies, is from Akron. Glassdoor’s content-moderation team is based in an office in suburban Akron, complete with Silicon Valley–style perks. Glassdoor was not a local startup, but its example shows that, as with Lebron James, even brain drain can ultimately prove beneficial to the community.

“Everywhere I go, I preach Akron,” James told a hometown crowd at an event after Cleveland’s 2016 NBA championship win. Akron gets a significant brand boost in the media from James, but his commitment is much more than symbolic. As the ESPN website The Undefeated noted, James has “built recreation centers, refurbished parks and upgraded basketball courts” and has “partnered with the University of Akron to put more than 1,100 students through college tuition-free.” James also hosted an Akron premiere for the film Trainwreck, a comedy in which he appears with Amy Schumer. He’s even opening a school. And though he recently left Cleveland to join the Los Angeles Lakers, his commitment to Akron will continue.

Yet Akron’s trajectory has been, as one local put it, “the smoothest downward escalator,” and it’s not clear that the slow decline has been arrested. Turnaround efforts based on increased immigration, downtown population growth, and innovative businesses are just getting started, as are neighborhood redevelopment initiatives.

Akron’s prospects are also limited by its location in the shadow of Cleveland. Akron’s Summit County and Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County are physically contiguous. In most other parts of the U.S., Cleveland and Akron might be considered twin cities, or twin poles of a larger metropolitan region—they’re just 39 miles apart. Akron and Cleveland instead see themselves as distinct cities, not as part of an integrated region. Proximity to Cleveland has unavoidable implications. Cleveland is the central hub of Northeast Ohio and disproportionately claims regional assets, like sports teams. Cleveland enjoys national name recognition and the lion’s share of national press. And it holds the regional advantage for attracting the urban millennial market. This geographic reality makes it exceedingly difficult for a middle city like Akron to do what, say, Grand Rapids has done in Michigan, where it has emerged as a genuine hub for the western part of the state, attracting people, jobs, and institutions. (See “Manufacturing a Comeback,” Spring 2018.) Akron probably won’t be able to do that. Instead, it has to figure out what its role is within the larger region, to make the geography and culture of Northeast Ohio work for it, not against it.

The city will need to leverage its culture and character for economic growth. Akron possesses quirky but interesting traits that set it apart from other cities, while also stamping its identity as a middle city. It’s a place where kids grew up with the sound of buzzing in the air—that meant that the Goodyear Blimp was flying overhead. It’s home to the All-American Soap Box Derby World Rally championship at Derby Downs, which attracts contestants from around the world. It was the longtime home of the Professional Bowlers Association—it doesn’t get more middle city than that—until former Microsoft executives bought out the troubled organization in 2000 and it moved to Seattle. Lay’s Guitar Shop has supplied guitars to musicians such as Joe Walsh and continues to sell custom and restored vintage guitars. Akron was the birthplace of the iconic oddball rock band Devo. It’s a city that possesses unique character traits, the kinds that add depth to a community. Akron should not run away from, or seek to homogenize, these features, but rather enhance them.

A host of small and medium-size postindustrial cities in the U.S. are struggling to reinvent themselves. Akron is better positioned than many, maybe even most. It has positives that some peer cities can’t match, and its decline was never as steep as for many others. Akron has yet to reverse industrial decline and create a truly new cycle of prosperity. In its success or failure in doing so, Akron could be a bellwether for many other middle cities facing similar challenges.

Top Photo: “Everywhere I go, I preach Akron,” says NBA great Lebron James, who grew up in the city. (MICHAEL CHRITTON/AKRON BEACON JOURNAL/ TRIBUNE CONTENT AGENCY LLC / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO)