In normal times, New York’s urban tapestry is made of sturdy material. Each thread tends to reinforce the others. Well-paid midtown office workers grab lunch and later get a haircut on their way home. Japanese tourists support Broadway, and Broadway, with its need for costumes, supports the Garment District. Programmers and graphic designers living in Brooklyn earn money from tech firms and banks in Manhattan. Business travelers support hotels. Hotel housekeepers take the money that they earn in midtown back to grocery stores in Queens and the Bronx. The Staten Island firefighter depends on tax revenues generated from this intertwined activity to pay his mortgage. Pull a thread out, and the fabric weakens. In early February, New York got a hint of this, when the first United States Covid-19 border closure, to Chinese visitors, left the Broadway box office down 4 percent.

The Covid-19 pandemic, and New York’s response to it, eventually ripped apart most of these threads. As the city’s multiple industries try to patch things together, urban complexity makes New York not more resilient but more fragile, at least for now. New York neighborhoods have varying layers of complexity, from close-knit outer-borough enclaves, whose residents eat and shop within walking distance, to midtown Manhattan, which depended, pre-Covid, on nearly 4 million daily visitors from around the world for its success. The less complex the neighborhood, the more straightforward its short-term recovery, provided the city implements the right policies. Midtown, as the most complex, is now the most vulnerable to a faltering recovery. The city, with state and federal backing, must enact the right policies to revive midtown, too.

The good news is that what made New York thrive, pre-Covid, hasn’t disappeared in half a year. People want to go out and be together, and thriving cities are where they do that. The bad news is that the longer the damaged parts of New York’s economy remain unattached, temporary changes become permanent. Small art houses close for good. Small retailers (and some big ones) with low profit margins pre-Covid go under, and nothing replaces them. By any measure, New York faces a daunting recovery—but it can do much to ensure that the industries that make the city unique, from funky fabric stores to big tech, from the big bank to the foreign-language bookstore, stick it out.

Before mid-March, New York City’s economy boasted nearly 4.1 million private-sector jobs—a record. No one industry dominated, meaning that the collapse of one would not mean disaster for the city. More than 800,000 people worked in “professional and business” sectors, which include corporate law and software design; another 800,000 worked in health care. Nearly half a million people labored in finance and real estate, and another half-million in leisure and hospitality. Retailers provided nearly 350,000 jobs; manufacturing, about 70,000; building construction, 50,000. There was basically a job for everyone, whether the investment-bank CEO or the dishwasher newly arrived in New York from Central America. Two earlier crisis periods—the tech bubble bursting, soon followed by 9/11, and then the 2008 financial meltdown—showed resiliency in this employment variety, as Gotham’s economy recovered far faster than the rest of the nation’s.

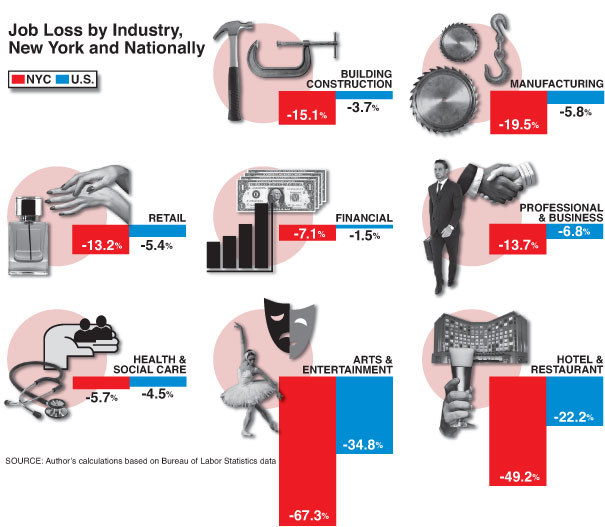

What was hard to imagine in early March is an awful fact now. Shutting down entire industries for months, even for a justified reason, brings mass-scale job destruction. As of late July (the last month for which data are available), New York City was missing 16 percent of its jobs, or 646,100 positions, relative to last July. After the financial crisis, by contrast, New York lost 206,300 jobs.

And in this crisis, New York is faring far worse than the rest of America. By late July, the nation had lost 8.1 percent of its jobs. But locally, industry after industry isn’t just in recession; it’s virtually nonexistent. New York is missing 53 percent of its 471,800 pre-Covid leisure and hospitality workers. The arts and entertainment field has lost 65,200 jobs, or more than two-thirds, and the restaurant and hotel field has hemorrhaged 184,500 jobs, or 49.2 percent. Retail outlets have laid off 45,300 people, or 13.2 percent. All these declines outpace national losses.

The disparity is due not only to the duration of New York’s lockdowns but also to the interconnections of the city’s industries, with Manhattan as the knotted center. A suburban Texas hairstylist depends, for her business, only on nearby residents. Midtown restaurants, by contrast, depend on a mixture of tourists, locals, and commuters. Even if the locals remain, restaurants will have difficulty surviving without all three groups. Manhattan’s retailers won’t survive solely on local window-shoppers; they need free-spending tourists. And without tourists to patronize restaurants and retailers, the storefronts shutter, making the streets less interesting—one reason fewer for locals to stay or for tourists to return.

The recession also has begun to slam industries that initially avoided closures. In finance and real estate, the city has lost 34,600 positions, or 7.1 percent of the total. It’s obvious that with demand for apartments down, fewer people need a real-estate broker. But banks have shed employment, too, with commercial banking giving up 1,800 jobs, or 2.5 percent, relative to last July, and investment banking losing 3,100 jobs, or 6.2 percent. The professional and business-services sector is down 110,300 jobs, or 13.7 percent, including many temp workers. A longer-term danger in these fields is not job loss but transfers, with Manhattan’s banks and law firms considering opening satellites in New Jersey and Westchester and basing workers at the office nearest their homes, at least some of the time.

As New York devises recovery policies, it should start with what’s working—relatively speaking. A visitor to one of New York’s many neighborhoods early this fall, walking around on a pleasant evening, would see what seems to be a healthy city. Outdoor restaurant tables on the Bronx’s Arthur Avenue and in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg and in many other areas are packed, a welcome bustle that the city must build on.

Outdoor dining was about the city’s only good news in recent months. Blair Papagni and her husband co-own Anella, a 12-year-old restaurant in Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood. A postindustrial community along the East River, Greenpoint benefits from a Covid-19 equilibrium. Its relatively affluent residents—the median household income is $86,000, 41 percent above the city average—are part of the “work-from-home” crowd. They’ve retained enough income to eat out but aren’t rich enough—or old enough—to decamp to a second home.

When New York State and City let restaurants offer outdoor dining, starting in mid-June, Anella’s customers returned. “We’re really lucky to be re-embraced by our community,” Papagni says. “We’re very fortunate to be a restaurant that already had outdoor dining in our back garden. It has a cover, even in the rain.” Though the restaurant, pre-pandemic, served some tourists venturing out of Manhattan, for now it depends on regulars living “within a two-block radius.”

Even so, Anella is struggling. Reduced capacity—until late September, restaurants could serve no one indoors—means that “we’re looking at maybe 30 percent of our regular sales,” says Papagni. Anella offers takeout but not delivery; the fees that firms such as Uber Eats and Grubhub demand are too high. Lower sales bring reduced hours and days. Papagni and her husband already shuttered a second restaurant, Jimmy’s Diner, in Williamsburg, after 13 years. The contract with the landlord was expiring, and she “did not see a scenario in which indoor dining was going to come back in a significant way before our lease was up.” Between Jimmy’s closure and Anella’s reduced service, staff has fallen from 22 to seven.

Papagni’s landlord, a Polish immigrant, has been flexible. “My landlord is behaving in the way that all landlords should,” she observes. “He has seen the reality of the economic landscape around him. He’s being a decent person. He and I sit down on the first of the month and figure out what the rent is going to be. . . . I certainly want to pay rent, and he deserves to be paid, but I can’t pay all of it right now.” For many other restaurants, operating at lower capacity and knowing that months of back rent hang over them, “it really is a hopeless situation,” Papagni says. An NYC Hospitality Alliance survey of 450 restaurateurs found that 34 percent paid zero rent during August, and 87 percent paid only partial rent. Of course, many small landlords of restaurants and retailers have their own mortgages—and hefty city property taxes—to pay.

Without rent relief, restaurant and retail-store owners will have one reason fewer to confront the prospect of future months—if not years—of lower revenues as the city recovers. Jan Lee, who owns a small property in Chinatown, notes that one of his commercial tenants, a high-end cosmetics and facial-services store, “has not paid since March.” In early September, the tenant proposed a 25 percent rent reduction, with the promise slowly to pay back the rent in arrears as business returns. “We have no intention of evicting her,” says Lee, but we “let her know we need to pay our taxes. . . . The proposal she came up with is reasonable. . . . If she loses her business, we lose the rent in arrears.” The city should create a consistent, predictable process to address past-due rents, with property-tax deferrals to small-business owners who agree to participate.

“The professional and business-services sector is down 110,300 jobs, or 13.7 percent, including many temp workers.”

Beyond rent measures, government can do smaller-scale things to help neighborhood businesses. For instance, state regulators could give restaurants an extra six months on expiring liquor licenses. “That would be enormously helpful to people,” Papagni notes. “If you were looking at your license expiring in January, you’re going to have to pay $4,500.” The city and state could also provide more consistent information to business owners. Though New York can’t predict Covid’s path, the state and city could explain what they would do in different scenarios. If virus cases rise above a certain level, will Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio shut down dining again? If so, both should make clear how they will determine that threshold. Restaurateurs need to be able to assess whether they can shoulder the risk of buying tens of thousands of dollars in perishable inventory.

Twelve miles from Greenpoint, Fordham Road, a commercial strip that traverses the mid-Bronx, is another resilient neighborhood. The Fordham Road area boasts a normally vibrant retail scene—electronic repair shops, a bakery, a mom-and-pop pharmacy, furniture and pet stores, and more. Here, “you have everything,” says Wilma Alonso, executive director of the Fordham Road Business Improvement District.

Compared with Greenpoint, Fordham Road has not fared well economically in the pandemic. Its residents, lower-wage service-industry workers—the median income is just $28,500—cannot work from home, and many have lost their jobs. While Greenpoint residents have largely kept their white-collar jobs, Fordham Road residents have received temporary benefits to make up for job losses. The area received extra federal unemployment benefits that Congress approved in April, designed to keep consumer spending from crashing. The supplemental benefits meant that people with lower-than-average wages—that is, most of Fordham Road’s residents—took in extra money, relative to their normal income, until late July. Now they can still collect normal unemployment to replace most of their income. “People are up and about,” observes Alonso. “People are shopping.”

Fordham Road faces another challenge, too: the lawlessness that broke out after the late May antipolice protests turned into riots. “The worst part for us is not the pandemic but the looting,” Alonso says. Of 75 stores, 27 in the corridor were looted in early summer. After 25 years of working in the area, she adds, “I never expected in my life to see something like that.” Though the victimized stores have reopened, they suffered significant financial damage. “People who say, ‘Oh, they have insurance’ ” don’t understand how insurance works, maintains Alonso. “You would never think of getting [an insurance] policy that would cover even the nails on the walls,” she says. “You would make an estimate: What can I lose over the year? Can I afford to lose $20,000?” Small firms have had losses of six figures or more. The city must prevent more looting. Just as restaurants can’t withstand multiple cycles of Covid closures, businesses can’t survive multiple attacks.

Quality-of-life issues are another concern, explains Alonso. Illegal vendors populate sidewalks, crowding customers who now must wait outside small stores in order to maintain social distancing. Panhandlers and mentally disturbed people harass passersby. The city is not responsive. If a homeless person is sleeping in front of a storefront, Alonso points out, the owner can call 311, the city’s computerized complaint system. But 311, in turn, calls social services, which, accompanied by police, ask the homeless individual if he needs help. If the person says no, the site is then logged on 311 as a location where the individual has refused help—and that completes the government response. Meantime, property and business owners must repeatedly clean up feces and urine.

The city’s short-term task for Fordham Road is to keep the neighborhood stable. Longer-term, though, New York’s commuting neighborhoods, absent a thriving Manhattan, will deteriorate. Unemployment benefits will expire; without the money that residents of the Bronx take home from their retail, restaurant, hotel, and other jobs in Manhattan, Fordham Road would get poorer as temporary job losses become permanent.

After Labor Day, Manhattan remained unraveled. Many real-estate executives estimate that fewer than 10 percent of office workers have returned, an assertion borne out by sparse foot traffic and transit statistics. Over the four working days after Labor Day, Long Island Rail Road traffic remained 72 percent to 75 percent below normal, and Metro-North Railroad traffic remained up to 80 percent below normal, indicating a dearth of white-collar office workers. Subway traffic, too, remained more than 70 percent below normal. Tourism is nonexistent. For now, New York hangs in a state of suspended animation. If you live in Greenpoint or near Fordham Road, you probably don’t think much about Manhattan’s day-to-day vibrancy. But the long-term loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs, high- and low-paying, would reverberate across the five boroughs.

“The problem with Manhattan business is that there is no business,” says Robert Schwartz, owner of Eneslow Shoes, with three locations, including one on midtown’s Park Avenue, from which it sells orthopedic shoes. “There is no retail business of any kind.” After Covid struck, Schwartz estimates, business at his mid-Manhattan store fell 97 percent. By Labor Day, it had recovered to around 30 percent of normal. “I think there’s a very good percentage of people who just left Dodge. They never came back from Florida. You know, my customers are older.” Responding to plummeting sales, Eneslow has laid off workers, going from 35, most of them full-time, to 19, all part-time.

For Schwartz, as for many retailers, Covid has accelerated preexisting problems. Eneslow, a century-old business taken over by Schwartz’s family in 1968, was already struggling against online sellers such as Amazon. The city’s tax and regulatory policies didn’t help. Schwartz says that he’ll need rent relief to keep his Manhattan store open. He suggests, too, that the city repeal its commercial-rent tax, a unique tax levied on Manhattan commercial renters, not their landlords. Even worthy reforms won’t alleviate the short-term problem: the dearth of office workers and visitors. Schwartz sells a specialty product, but he’s in the same boat as nearly all Manhattan retail: the daytime customer has vanished.

Across town, Mood Fabrics has a drastically different customer profile. The 44-year-old Garment District retailer sells creatively patterned fabrics to designers and home sewers from around the world. Before Covid-19, Mood attracted 1,200 customers daily. Now, three months into its reopening after the government-mandated shutdown, sales are, “on a positive day, 50 percent of what we’re used to,” says Eric Sauma, coproprietor.

It’s not that people no longer want to buy fabric or are buying it online. “We sell a tangible product [that] people need to feel [and] touch,” Sauma says. In fact, Mood has some new business: people are making masks, and others with free time are trying their talent at clothes-making. “We have a lot of home sewers, mask makers, fashion students, people who go to [the Fashion Institute of Technology or to] Parsons, who are still in New York City,” Sauma says. There’s a “good resurgence of young designers who are just saying, ‘I’m bored, I’ve been collecting money at home.’ ”

But the Garment District depends on midtown’s complex economy. “A big portion of our business is Broadway,” notes Sauma. “A good thing about Broadway is that they need fabric for all the shows; they have a lot of costume shops. That portion of our business is completely stopped.”

Yet people still desire unique retail. A few blocks away, on Sixth Avenue, the Japanese-language bookstore Kinokuyuna and the unique beading-craft store next to it are often close to retail capacity. Small groups also line up outside the Lego Store and the American Girl store at Rockefeller Center, desperate for something fun for their kids. Quirky small retailers and destination larger retailers can survive—with some help from smart city policies. Sauma concurs on the need for commercial-rent relief; he’s paying his rent, but of the 16 units in his building, four have shut down and five have stopped payment.

“I think that a breaking point is going to come now,” Sauma says. “Between the Port Authority and Times Square, it doesn’t help us that Eighth Avenue has turned into a homeless shelter,” he says. He took his children to a doctor near Washington Square Park, and, while waiting in the car, “Lo and behold, a man fully exposed [was] walking down the street. . . . That’s not something you want your kids to see.”

There is no reason to visit New York—or, for many, to return to the office—if the city’s cultural venues and world-class restaurants and retailers remain shuttered. The longer that office workers and tourists stay away, though, the longer that arts groups, restaurants, and retailers go without adequate revenue, driving more businesses under in a destructive cycle.

A Partnership for New York City survey found that workers don’t prefer to stay remote five days a week. “People describe getting back to the office, even in this regulatory environment, with words like . . . ‘invigorating’ and ‘Zen-like,’ ” says Jordan Barowitz, spokesperson for the Durst Organization, which owns both commercial and residential buildings in the city. Yet for now, at least, the office isn’t quite the office. “I could come back,” says one finance worker. “But when you read the rules—you have to wear a mask if you talk to someone, no meetings with more than six people, you can’t use the conference room—what is the point? We’ll just be having Zoom calls at our desks.” Most are staying away from reopened offices for other reasons, according to the Partnership poll, including lack of child care at home—with kids still not back to full-time school attendance—and fear of taking mass transit.

For decades, since 1980s-era Metropolitan Transportation Authority chairman Richard Ravitch persuaded businesses to back the rebuilding of the subways, New York’s commercial real-estate owners have paid attention to transit adequacy. Without effective transit, workers can’t come to work in their high-rent office buildings. But the pandemic revealed a stark new reality: white-collar employees may not want to work remotely, at least not five days a week, but they have now proved that they can do so, if need be. Thus, even as the state-run MTA is looking at deep budget deficits and service cuts, it must somehow offer a better quality of commute than existed pre-pandemic, or white-collar workers will likely make the trip into the city less often.

As finance, law, and other high-paying industries remain quiet about future plans, one sector has recommitted to New York—ironically, the one that enabled working from home. “The only companies that have doubled down on New York are tech companies,” says Julie Samuels, executive director of Tech:NYC, an advocacy group, citing Facebook’s going ahead with a new lease at Hudson Yards on Manhattan’s West Side and Google’s commitment to its Hudson Street development plan, farther south in Manhattan.

With midtown Manhattan eerily empty, it’s refreshing to hear someone so enthusiastic about the city’s future. “Tech is committing, quite frankly, for the same reasons as before the pandemic,” says Samuels. “New York is still the center of so many industries, even if people are working at home. It still feels like the center of the universe. There are certain people—I know because I am one of them—who always want to be in a big city. Tech will always want to hire those people.” Samuels has one caveat: “As long as we can find a way to provide safe access [on] transit. We need to figure out a way to keep the subway functioning.” She’d also like to see new bike and bus lanes and “micro-mobility” options, such as electric scooters, to “get [people] out of private cars.”

The arts may be the portion of the economy hardest to reopen. In 2019, nearly 14.8 million people saw a Broadway show. Sixty-five percent were tourists, and 19 percent were from abroad. Tourism as an industry requires big crowds to flourish, something that the fight against Covid-19 has made impossible. The performing arts have borne the brunt of pandemic closures. In late September, the Metropolitan Opera said that it would remain closed for at least another year, with other arts groups likely to follow. Without performing arts, tourists won’t return, at least not in large numbers.

Museums have begun to come back to life. It was heartening, in late August, to see the Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA reopen to limited-capacity crowds. Right now, says Ken Weine, spokesman for the Met, “upward of 80 percent of our visitors are local, regional”—normally, tourists make up 70 percent of the Met’s visitors. To encourage museumgoers still nervous about mass transit, the Met has started a free bike-parking valet service, sponsored by Transportation Alternatives. The museum’s reopening—albeit at an average of just 5,500 daily, compared with 25,000 for a normal busy day, pre-lockdown—is a relief to culture-starved New Yorkers and to nearby businesses.

But operating at reduced capacity, and without tourists, is having a cataclysmic impact on the Met’s budget, which depends on admission tickets, retail and food sales, and memberships, as well as on donors. “We’re starting from almost zero, in terms of how long it will take tourists to come back,” Weine believes. The Met, with its over $3 billion endowment, and a new $25 million relief fund raised from wealthy trustees, is in a stronger position than most arts groups. For lots of cultural institutions, it’s “an existential challenge,” Weine says. It’s an existential challenge for New York, too; for many wealthy residents, who disproportionately pay city taxes, one of the main reasons to stay in the city is proximity to the ballet, classical music, and the museums.

Confronting the biggest crisis that New York has endured in at least 45 years—maybe ever—elected officials have been bizarrely sanguine about the city’s well-being. “For a city hall that believes in an activist and interventionist government, they have an amazing confidence in the invisible hand of capitalism to jump-start Manhattan’s economy,” says Barowitz. Neither Mayor Bill de Blasio nor Governor Andrew Cuomo seems to think much about Manhattan and the challenges of its recovery—or the repercussions for the city’s other boroughs if Manhattan doesn’t bounce back to its old self.

New York is not a barrel of oil: when the price goes down, demand won’t naturally go up. In the 1970s, when middle-class residents and their employers fled Manhattan, newcomers didn’t immediately take their place, renting apartments or office space at now-lower prices. Lower demand for housing in unemployment- and crime-ravaged South Bronx, Bushwick, and Harlem neighborhoods resulted in destruction of the supply of apartments, via fire and neglect, not price declines that spurred higher interest. New York was lucky after its previous nadir, in the 1970s. Many American cities never recovered their populations after the tribulations of that era; they still launch serial failed experiments to revive long-desolate downtown business districts.

New York’s future is uncertain, but government can do much to ensure that the world continues to choose the city as a home, office, or place to visit. Gotham can protect the quality of life from Fordham Road to Eighth Avenue. The state can ensure that mass transit improves, rather than crumbles, so that riders come back. Both levels of government can mediate commercial-rent relief, coupled with property-tax relief for owners who agree to ease up on rent. A sales-tax holiday for retailers and restaurants, from October through the holidays, at least, would entice shoppers and diners back. Underpinning all this, New York will surely need more federal aid directed to attaining such goals. If it can reach the other side of the pandemic, New York City can live again.

Top Photo: Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images