It may be that the best book that will ever be written about today’s progressive mind-set was published in 1941. That in The Red Decade author Eugene Lyons was, in fact, describing the Communist-dominated American Left of the Depression-wracked 1930s and 1940s makes his observations even more meaningful, for it is sobering to be confronted with how little has been gained by hard experience. The celebration of feelings over reason? The certainty of moral virtue? The disdain for tradition and the revising of history for ideological ends? The embrace of the latest definition of correct thought? Lyons was one of the most gifted reporters of his time, and among the bravest, and his story of the spell cast by Stalinist-tinged social-justice activism over that day’s purported best and brightest—literary titans, Hollywood celebrities, leading academics, religious leaders, media heavies—would be jaw-dropping if it weren’t so eerily familiar.

Indeed, looking backward from a time when, according to surveys, more millennials would rather live under socialism than capitalism, it’s apparent that Lyons was documenting not just a historical moment but also a species of historical illiteracy as unchanging as it is poisonous, its utopianism able to flourish only at the expense of independent thought. On a range of issues, alternative views were defined as not merely mistaken but morally reprehensible; and among the elites who dominated the cultural sphere, deviants from approved opinion were subject to special abuse. Of course, having lived and worked in Soviet Russia, Lyons made distinctions about relative abuses of power. Under Stalinism, dissidents were liquidated, or vanished into the gulag; the American Left could only liquidate careers and disappear reputations.

It’s not surprising that during those desperate Depression years, the program of the Communist Party USA would have held such wide appeal, especially among the young. Who else stood up so adamantly—or at all—against Jim Crow? Who stood so fearlessly on the front lines with labor against the power of rapacious big-business capitalism? What other party spoke so passionately for peace and justice? Soviet Russia was nothing less than the future of humanity! There, all were free and equal, poverty and oppression banished, and food, lodging, and health care guaranteed! As screenwriter Richard Collins would later recall of his time in the party, Communism was, for its devotees, “a cause, a faith, and a viewpoint on all phenomena. A one-shot solution to all the world’s ills and inequities.”

While CPUSA membership likely never exceeded more than 75,000—and even for many of them, the particulars of the Communist political program surely registered as mumbo jumbo—fellow travelers numbered in the millions, and Communist-backed special causes, each near-biblical in its moral sweep, brought multitudes to the streets. Sacco and Vanzetti. The Scottsboro Boys. Republican Spain. And the pageantry and the music—Woody Guthrie ballads and labor anthems like “Which Side Are You On?” and Paul Robeson’s Godlike basso profundo on the Victrola in every left-wing home, with his heartrending dirge to the murdered union man Joe Hill. It was a movement built on high-octane emotion and blind belief.

That it was all a colossal fraud was obvious all along, or should have been. For anyone willing to see, Stalin’s Russian paradise was a totalitarian horror show, equaled only by Hitler’s Third Reich. For all the regime’s numerous apologists in the press, led by the New York Times’s Walter Duranty (who won the Pulitzer Prize for his efforts), word of the true state of affairs in Russia was not hard to come by because by the mid-1930s, reports on the Great Famine (the planned execution by starvation of millions of recalcitrant Ukrainian peasants) were too persistent to ignore without sustained effort. So, too, were those of systematic state thuggery, culminating in the confessions-by-torture of veteran Bolsheviks in the purge trials of 1937–38 and, in Spain, in the guise of fighting fascism, the systematic elimination of rival leftist parties by Soviet secret police.

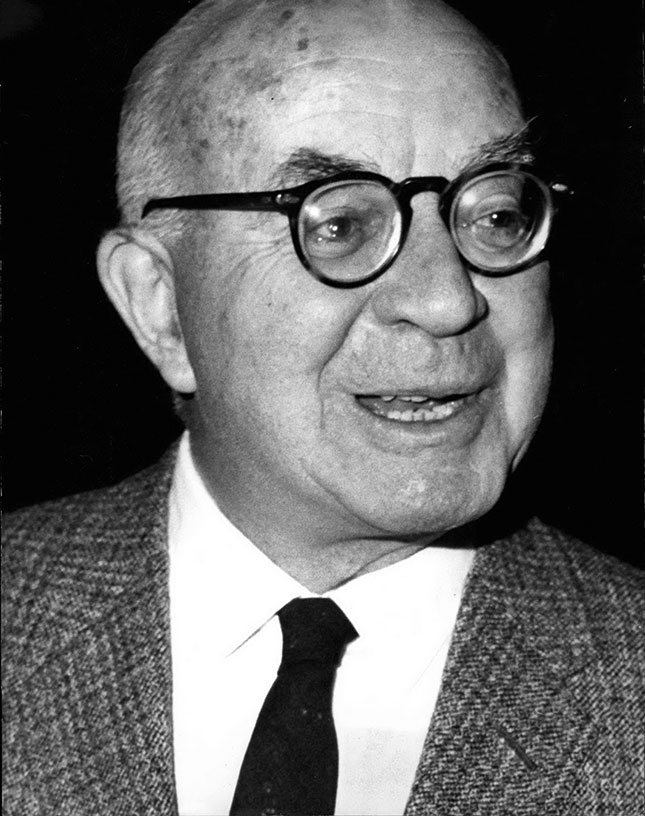

By the time he published The Red Decade, Lyons, a rare journalist given to damn-the-consequences honesty, had come to know his twin subjects exceedingly well—that is, Stalinism and the American liberals so ready to overlook its savage immorality. Having arrived from Russia as a small child and grown up in the poverty of the Jewish Lower East Side, he came of age a committed leftist, and, as he’d later acknowledge, when he returned to the land of his birth, in 1928 as a 30-year-old correspondent for the United Press, his aim was to use that privileged perch to promote the Revolution. It was on this basis that, in 1930, he scored a stunning journalistic coup that brought him worldwide recognition: the first-ever interview by a Western correspondent with the reclusive Stalin. And, to his subsequent shame, he joined other leading reporters in mostly running cover for the regime, including on the famine.

Within a few years, though, he began harboring doubts, and before long he was running afoul of Soviet censors by finding ways to alert readers to the regime’s hypocrisy and cronyism, the failure of its various economic plans, and, especially, its ruthlessness and brutality. “The most dangerous people have always been those most ready to sacrifice themselves for a cause,” he wrote on his return home, with the clarity of the chastened zealot, in his 1937 memoir Assignment in Utopia. “The first expression of that disrespect for life is a readiness to sacrifice the lives of others.” Whittaker Chambers, who, a decade later, would identify the State Department’s Alger Hiss as having been a fellow Soviet agent, wrote in his autobiography Witness that Assignment in Utopia was among those works “that influenced my break with Communism.”

Yet at least as troubling to Lyons as the reality of the Soviet paradise was the refusal to face it that he encountered in America on his return. To the contrary, he ran up against an almost perverse eagerness to embrace every fabrication in its defense and to cast doubters as hostile to all that was good and true. Stalinist methods, if even acknowledged, often met with tacit approval. Was it not true that foes of the Revolution were plotting on all sides—reactionaries, Trotskyists, other class enemies? As the New York Times’s Duranty famously summed it up, “you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.”

That during those Depression years, the legions of starry- and steely-eyed included a disproportionate number of what we’d now call millennials was unsurprising; for the idealistic, emotion-driven young, hard questions always have easy solutions, and even in good times, there’s no competing with the romance of the Left. But what Lyons found far more unsettling was the credulity of those in the vanguard of progressive thought: leading figures in academia, entertainment, publishing, media, and the highest councils of government, from New York to Hollywood and everywhere between. These were the powerful and influential, the men and women who shaped public attitudes and opinion. While among them were many convinced ideologues, more numerous still were the careerists, or those simply following political fashion, sentimental liberals drawn to causes by the magic words: “justice,” “democracy,” “peace.” Lyons well understood the seductive power of the call for fundamental social transformation, but he also knew, as did few others, that it invariably led to the naming of enemies and the doling out of retribution, and to unspeakable moral chaos—and, moreover, that it didn’t even work.

In The Red Decade, Lyons charted how so many in positions of power and responsibility had come to think and say idiotic and often dangerous things with great seriousness. How had America lost such faith in itself and its guiding institutions, leaving capitalism (for all its attendant faults) under siege as the collectivist ethos gained greater currency? His was a clarion call to sanity and a plea that totalitarianism be seen for what it was, before it was too late.

In one sense, the book could hardly have appeared at a more propitious moment. As Lyons wrote in his introduction, it was originally to go to press on June 22, 1941—the very day that Hitler stabbed his ally Stalin in the back by invading the Soviet Union, thereby necessitating a wholesale revision of the CPUSA’s line on the European war. Already that line had drastically changed once, only two years earlier, instantly moving from die-hard anti-Nazism to adamantly antiwar, when Stalin shocked the world by signing his infamous nonaggression pact with Hitler; as a result, thousands of anguished party members had quit, and multitudes of fellow travelers quietly slipped away. But the hard core had rationalized, casting Stalin as a master statesman who had done what he had to in defense of the world’s lone socialist republic, and now they rationalized again. As Lyons observes with bemused contempt, though on that same June 22, the Communist front American Peace Mobilization had been in the midst of a “peace vigil” at the White House, for this “disciplined, obedient and fanatically self-righteous army,” the “ ‘plutocrat’ war was magically transmuted into a people’s war for freedom and justice.” The new demand was that America immediately get into the fight!

Never had the party been more fully exposed as the wholly owned subsidiary of a foreign power that it had always been. In the wake of the crude line-shifting and backpedaling, as a brand (if not as a political philosophy), for the CPUSA, the jig was pretty much up.

Ironically, in the short term, the timing hurt sales of Lyons’s book. For as the Germans scored victory after early victory in the East, Americans’ sympathies were naturally with the beleaguered Russians; and soon we would indeed be in the war ourselves, with Stalin cast (by Hollywood and elsewhere) as our partner in the fight to save civilization. Few in the reading public were interested in seeing Russia disparaged.

But Lyons’s message was timeless, and the book found new life in the vastly changed circumstances of the early Cold War. And reading it today, it is hard to resist the impulse to pause every few minutes to underline a sentence or leave a bold exclamation point in the margin. A serious thinker, Lyons was also a graceful stylist, given to mordant humor ideally suited to the task. The world he described was nothing if not target-rich, and he had taken notes and named names.

He acknowledges that most who followed the leftist line meant no evil—he calls them the Innocents Club, “high minded, idealistic, eager to be useful. . . . Not their hearts, but the organs located in their skulls, were at fault.” Still, he gives no one a pass. Decades before Tom Wolfe wrote Radical Chic, Lyons showed a special disdain for the wealthy who embraced radicalism to salve their guilty consciences. Perhaps the most prominent of these was Corliss Lamont, son of the chairman of J. P. Morgan & Company, who, as head of the Friends of the Soviet Union, emerged as the chief public apologist for Stalin’s crimes. As Lyons wrote, Lamont spared “neither his money nor his energy in defending the mass slaughter in Russia, and in damning those who dared examine that horror.” Affronted, the multimillionaire sued. The suit went nowhere, but Lamont’s grandson is today governor of Connecticut.

Over the course of 400 pages, Lyons covers the cultural landscape, alighting in turn upon all the capitals of progressivism, at each point examining the behavior of its most celebrated denizens when it mattered most. There were the men and women of letters, almost all dedicated foremost to status within their own insular universe. “Small in number, their impact on a nation’s mind is subtle and incalculable,” Lyons wrote. “They set the styles in not thinking.” At one point, he details a petition signed by nearly 150 of the day’s most notable writers, artists, and composers asserting “the weight of evidence established a clear presumption of guilt” of the Soviet purge defendants and cheering the verdicts as essential to “the preservation of progressive democracy.”

Then there were the professors and administrators at esteemed universities, then, as now, given to political correctness in every particular: “College teachers slanted their lessons to match the latest views out of Moscow, and met with the communist faction among their students in conspiratorial caucuses.” Much as he faults young people for their susceptibility to socialism’s appeal, Lyons faults even more the grown-ups, observing that views of the young are always “crudely colored by undefined emotional urges,” which leaves them “perfect raw stuff for demagogic molding. . . . [T]he glorification of youth is a modern development, it puts a premium on lack of experience, mental fuzziness and intuition as against intelligence and maturity.”

Hardly least, there were those in the left-of-center media who habitually assumed the worst about their own country. “Well, in America we executed people for murder and for holding unorthodox political opinions,” as he quotes The New Republic’s defense of the Moscow purge trials, but “in Russia they execute people for abusing positions of high responsibility. Are official rifle squads of the Cheka any more depressing to the morale of the workers than the hired Cossacks of the American mill towns? Are they any worse than the New York police?”

But in this saga of equal parts moral blindness and impenetrable self-righteousness, it is Lyons’s extended treatment of Hollywood that will likely strike contemporary readers as most familiar. For while the film community had more than its share of those steeped in Communist Party doctrine, the Party’s great achievement was in making leftism fashionable. “I saw Social Consciousness quicken and come to a boil in actors, writers and directors whose names rival Rinso and Camels as household words,” he writes of witnessing the spectacle at close hand. “The political pig-Latin of class struggle, anti-fascism, and revolutionary tactics rippled around swimming pools and across dance floors. . . . They had not the remotest idea what communism was in terms of economic structures or political superstates. For nearly all of them it was an intoxicated state of mind, a glow of inner virtue, and a sort of comradeship of super-charity.”

Adhering to the right beliefs and supporting the right causes was not just how to fit in, but how to get ahead. For those on the rise, or hoping to be, it “became the shortcut to success. At ‘cause parties’ they rubbed shoulders and bosoms with big shots they could not have met otherwise. Those who tried to detour the revolution, unless they were stars well fixed in the firmament, found themselves slipping from favor. It was at once a movement and a lobby, a religion and a racket.”

Perhaps the most memorable episode Lyons recounts in this regard is that of the so-called new Declaration of Independence, a document promulgated in 1938 demanding that America put the screws on Hitler by cutting off all economic relations with Germany. With Hitler and Hitlerism already well on their murderous march, such a position seemed unassailable, and film royalty rushed to sign on, “not knowing or caring,” as Lyons observes, “that it was at bottom another communist fund-raising and propaganda stunt.” Part of the Declaration’s ingenious appeal was that “signing on” was not so simple. Since the original Declaration, in 1776, had only 56 signees, this one would be limited to the same number. Thus arose a cutthroat competition for inclusion rivaling that surrounding the Oscars, and, as cameras recorded the signing ceremony beneath the floodlights at Twentieth Century Fox, the winners were called up by name and stepped forward to sign. Among them: Joan Crawford, Myrna Loy, Edward G. Robinson, Rosalind Russell, Henry Fonda, Claude Rains, Groucho Marx, and James Cagney. To keep the propaganda ball rolling and sate the envy of self-important luminaries elsewhere, ceremonies were now arranged in other cities, starting in New York, each also limited to 56 lucky signatories.

Alas, the timing proved less than ideal: as the Declarations tour was unfolding, Stalin signed his deal with Hitler, and suddenly America had no business taking sides. “The drama had turned to farce,” observes Lyons, noting that the tour’s public face, writer/director Herbert Biberman, later one of the Hollywood Ten, swiftly “apologized for having been temporarily a war monger.”

Given his intimate acquaintance with the Left, Lyons well knew what calumnies the publication of The Red Decade would bring down on his head. At the time, especially in elite circles, the charge of “red baiting” was akin to that of racism, sexism, or homophobia today; whether made in anger or with premeditated intent, it was enough to halt any challenge to the Left’s worldview. It was a weapon deployed, he wrote, by “literary critics, book reviewers and political commentators . . . a neatly contrived device for heading off free and uninhibited discussion of little things such as man-made famines, horrifying blood purges, forced labor on a gigantic scale.” In fact, in almost every meaningful arena of American life, those who “ran afoul of the revolution were made to feel the full weight of their crimes; they were ostracized socially, handicapped professionally and not infrequently stripped of their jobs as well as their reputations for ordinary decency.”

Lyons’s own world of book and magazine publishing was so dominated by leftists that former adherents who turned against the Party, deemed “moral monsters and turncoats,” could be made essentially to evaporate from mainstream view. He lists no fewer than 30 writers who suffered that fate during “the intellectual red terror,” including (as if to underscore the point for contemporary readers) such now largely forgotten former luminaries as Max Eastman, John Dos Passos, and James T. Farrell. He includes himself on that list. “The part I cannot induce the uninitiated to believe is how effective the terror could be,” he writes. “When you first met a particularly far-fetched libel on your character, it merely seemed funny in its absurdity.” But continually repeated, he adds, the lies take their toll, for wherever one tried to make one’s way professionally, “there were manuscript readers, casting directors, book reviewers who—consciously or by a sort of pack instinct—took their prejudices ready-made from the Popular Front comrades.”

The case of Dos Passos is especially telling. In 1936, as a man of the Left, he was among America’s leading novelists—arguably Hemingway’s closest rival, having just published the third volume of his USA trilogy to wide acclaim, including a cover story in Time. It was thus understandable that he was among those recruited, along with Hemingway, to travel to Spain to make a film in support of the Republican cause. However, while there, Dos Passos began making inquiries about a close Spanish friend who’d unaccountably vanished, and eventually learned that Stalin’s secret police had murdered him. Belatedly, his eyes were opened to the bloodcurdling reality behind the myths so artfully propagated at home. Worse, he refused to stay quiet about it.

Lyons recounts the episode only briefly, making the point that, as a result, when the celebrated author’s next book was published three years later, critics discovered “that Dos Passos had never really known how to write.” The story was told in greater depth by historian Stephen Koch in his book The Breaking Point. With access to Dos Passos’s unpublished notes, he includes a chilling account of Hemingway’s last meeting with his onetime friend. Dos Passos plaintively asked, “What’s the use of fighting a war for civil liberties, if you destroy civil liberties in the process?” Hemingway shot back: “Civil liberties, shit. Are you with us or against us?” Then, getting no reply, he lifted a clenched fist to the other’s face: “You do that and you will be finished, destroyed. The reviewers in New York will absolutely crucify you. These people know how to turn you into a back number. I’ve seen them do it. What they did once they can do again.”

Another figure who makes a brief appearance in The Red Decade is screenwriter Morrie Ryskind, and his example speaks to the influence that his leftist foes would continue to wield years after The Red Decade’s publication—even during the blacklist years of the late 1940s and early 1950s. One of the industry’s most successful writers, he had numerous credits, running from the Marx Brothers’ Animal Crackers and A Night at the Opera to My Man Godfrey and Stage Door. Ryskind broke ranks in 1947 by testifying in open session about Communist influence in the film industry. “In the twelve years prior to my testimony,” he’d write in his memoir, I Shot an Elephant in My Pajamas, “I was consistently one of the ten highest paid writers in Hollywood. I turned down, on the average, at least three assignments for every one I accepted, and I feel safe in saying I was welcome at every studio in town. After I testified against The Hollywood Ten, I was never again to receive one single offer from any studio.”

Few today, and fewer still in Hollywood, will summon up much sympathy for those like Ryskind. In the contemporary view, as expressed in books, movies, and PBS documentaries beyond counting, outspoken anti-Communists of that era were the equivalent of Salem’s fanatics, paranoids fixated on a nonexistent international Communist conspiracy, while those who refused to cooperate (and paid with their livelihoods) were heroic martyrs to free speech and free thought. Morally complex as that moment was, there were those on each side who fit these characterizations, and, of course, there’s no question that the anti-Communist crusade swept up a great many more of Lyons’s credulous Innocents than actual or even potential subversives. Yet it’s also true that there were at least a handful who’d long since dispelled all doubt that their overriding loyalty was to the Stalinist state and, in some cases, had proved their ruthlessness in advancing its aims. And one can only shudder at what might have happened had their ilk achieved political power equal to their cultural influence.

History didn’t play out that way. To the contrary: the fall from public grace of that era’s radical activists was so steep that for those growing up in the postwar years, the very word Communism was all but synonymous with barbarism and the crushing of the human spirit. For all Americans’ internecine quarrels over that time, and the doubts sown by Vietnam and Watergate, for five decades few questioned who were fundamentally the good guys and who were the bad, in the grand scheme. As late as 1989, in the jubilation following the fall of the Berlin Wall, it would have been hard even on American college campuses to find many who didn’t believe that a profound evil had been defeated.

That’s no longer the case today. From the Soviet gulags and the brutal crackdowns in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, to children turning on parents during the Cultural Revolution and the Cambodian genocide, much that was once common knowledge seems to have been forgotten or gone unlearned. How many schools still make Orwell required reading? How many college history majors have even heard of the masterwork of his fellow prophet, Arthur Koestler, author of Darkness at Noon?

In today’s Hollywood, where the 1950s blacklist stands as the great modern cautionary tale of the human capacity for evil, those with less than exemplary progressive politics routinely feel impelled to hide the fact from even close friends, and one can only guess at the grim fun Lyons would have with Tinseltown’s ever-changing victim power ratings. Whose heroic struggle for justice constitute the hottest properties this week: women, African-Americans, gays, transgenders? Never mind that their box-office appeal is likely to extend no more than five miles beyond the studio gates.

For all the Left’s capacity to shape opinion in Lyons’s time, the power wielded by today’s progressives is even more malign, for its heavy hand is all but unconstrained by countervailing forces. For one thing, 70 or 80 years ago, organized religion held such sway in America that even committed leftists understood that it could be derided only behind closed doors; and while there were some prominent clergymen who fell hard for the progressive line, they usually made sure to do so only as private citizens. Even they would have dismissed as lunacy the possibility that one day not only their congregants, but entire religious orders, might be widely characterized as dangerous zealots for adhering to traditional beliefs, or that agencies of government would compel them to violate their most deeply held spiritual convictions.

Even more so, business and industry stood as bulwarks against fundamental threats to the ways Americans thought about themselves and the world. Softheaded sops like Lamont notwithstanding, 1930s radicals were realistic enough not to seek influence within that all-vital power center. Why would they, given that they defined practicing capitalists as class enemies, so inevitably destined, one way or another, for elimination? Yet today, with the Left driven by a different, if no less bizarre, notion of the ideal equitable society—one where individual merit is trumped by race, gender, and sexual orientation—CEOs of multinational firms cower, lest they be found insufficiently committed to diversity or otherwise fail to heed the harsh dictates of identity politics. Mozilla chief Brendan Eich gets fired for contributing to an anti-gay-marriage initiative; Google dispatches James Damore for a memo questioning the company’s ideological mono-culture; Papa John’s namesake founder is dumped after quoting someone else’s use of the N-word as a negative example in a public-relations session. We may not hear the word “Stalinist” much any more, but this is stuff right out of the intellectual red terror.

At least rhetorically, the Communists of the late 1930s were, in fact, far less hostile to the American idea than are today’s run-of-the-mill progressives. In an age where Americans were raised to revere their country’s singular history, they all but wrapped themselves in the flag. “Communism Is Twentieth-Century Americanism” went the party’s famous Popular Front slogan, and they did not hesitate to name their Spanish battalions for Lincoln and Washington or the Party school for Marxist instruction after Jefferson. The contrast with today’s Left, which sees American history as a cavalcade of oppression, could not be more striking. Little wonder that today’s Democrats, seeking to stay abreast of their fervent base, are as publicly invested in identity politics and collectivist economics as the denizens of any faculty lounge.

Indeed, this speaks to the most striking difference between the world that Lyons described and the one we contend with today: it’s no longer a tiny, if disproportionately influential, political entity waving the Left’s banner; it’s one of the two major parties. True enough, the Democrats have long cast themselves as the party of the dispossessed, and their policies have steadily moved the country leftward; and it is also the case, as Lyons recounts, that during the New Deal years, leading administration figures, including Eleanor Roosevelt, unknowingly served as props at Communist-sponsored events advertised as “democratic and anti-Fascist.” But following the Hitler–Stalin pact, even Mrs. Roosevelt distanced herself from the radicals. From then on, and nearly to the present day, the self-evident superiority of the capitalist over the socialist model was mainstream doctrine in both parties. No more.

Eugene Lyons was certainly a cynic, but unlike his fellow ex-leftist Whittaker Chambers, who famously declared, “I know I am leaving the winning side for the losing side,” he was not a pessimist. For the rest of his life, he pressed on with the hard work of truth-telling and persuasion—notably, as a founding contributor to National Review, where he helped set the course of postwar American conservatism and, in one especially vital exchange with John Birch Society founder Robert Welch, powerfully made the case against the Right’s tendency to succumb to the same paranoia he’d seen operate to such destructive effect on the left. He would live long enough to celebrate the Reagan revolution, dying in 1985 at the age of 86. By then, the widespread prominence that he’d enjoyed in his early days on the left was long past, but some progressives never forgot or forgave. Random House founder Bennett Cerf, a leading sentry at publishing’s gates (and a much-loved, avuncular TV personality), once publicly likened Lyons to Mississippi’s notorious senator Theodore Bilbo, whose name was synonymous with virulent racism.

Long before, Lyons wrote in The Red Decade: “I have known men and women so frightened by the certainty of persecution from the Left, that they hid their doubts and disillusionments like criminal secrets.”

That was not his way. He knew what he’d signed up for, and never stopped taking the attacks for what they were: confirmation that he was doing something right.

Top Photo: Carrying likenesses of Lenin, Stalin, and other revolutionary leaders, between 40,000 and 60,000 Communists march on May Day in New York City, 1935. (MURRAY BECKER/AP PHOTO)