Among the many eruptions of outrage that distracted us from the dread of the past year was one provoked in December by an 800-word Wall Street Journal op-ed titled “Is There a Doctor in the White House? Not if You Need an M.D.” Written by prolific author and veteran wit Joseph Epstein, it mocked First Lady–to–Be Jill Biden for wanting to be called “Dr. Biden.” The honorific should be reserved for the kind of doctor who could save your life when your appendix bursts, he wrote, not a doctor of education or, as they are commonly known, an Ed.D.

Epstein touched a cultural nerve. A Biden administration spokesperson described the article as a “disgusting and sexist attack” and demanded an apology and a retraction. The Guardian, late-night host Stephen Colbert, and MSNBC all jumped in to defend the First Lady’s honor. Northwestern University, where Epstein taught for 30 years, still has a message on its website assuring visitors that his “misogynistic views” are not its problem, since Epstein hasn’t been a lecturer there since 2003. Social media added to the chorus: Dr. Biden “worked [her] rear end off for years to earn that,” tweeted Audrey Truschke, an associate professor of South Asian history at Rutgers University. Let her “shout it from the rooftops.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

The outrage was ephemeral but also revealing. Stuck in the stock framework of sexism and unduly reverent of academic title and prestige, Team Dr. was tone-deaf to the cultural and political moment. The controversy unfolded a mere four years after a presidential election that exposed an ominous social and economic chasm between college-educated and less diplomaed Americans. It coincided with a lame-duck president who “love[d] the poorly educated” rallying his base to help him undermine the results of an election that had not gone his way. But instead of minding the polarizing education gap, Dr. Biden and her advocates stood staunchly on the side of a powerful education-industrial complex and the professional-managerial class that it nurtures. In fact, the First Lady’s Ed.D. epitomizes today’s rampant degree inflation and meritocratic jockeying, which—ironically, given the politics of her husband’s administration—weighs most heavily on young adults, especially the least advantaged.

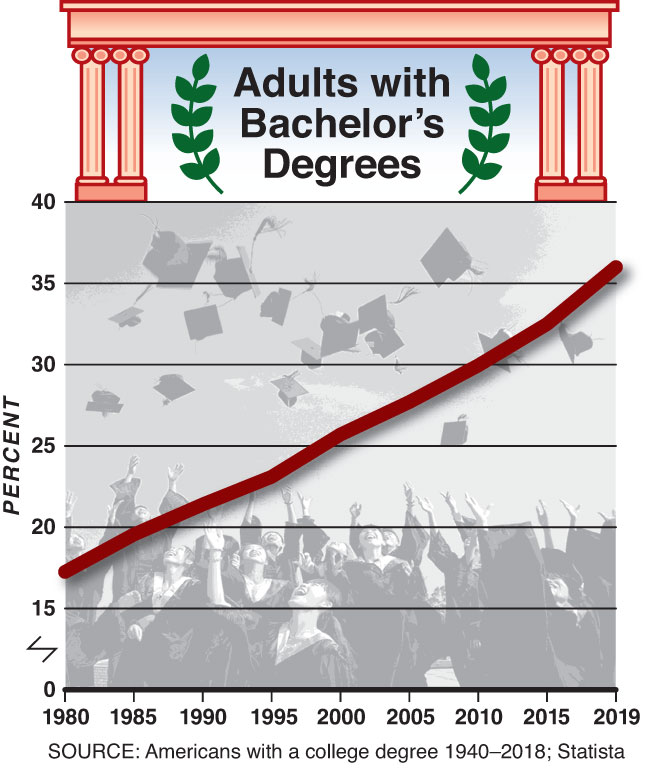

Start with those degree-inflation numbers. Between 1980 and 2017, the share of adults with at least a four-year college degree doubled, from 17 percent to 34 percent. The Great Recession intensified the trend, since people often choose to return to school to burnish their résumé when finding jobs is tough. From 2010 to 2019, the percentage of people 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher increased by 6 percentage points, to 36 percent, where it sits today.

The more surprising part of the story is that the college degree is declining in status: postgraduate degrees are now where the real action is. The coveted B.A. from all but the most elite schools has become a yawn, a Honda Civic in a Tesla world. It’s not just metaphorical to say that a master’s degree is the new bachelor’s degree: about 13 percent of people aged 25 and older have a master’s, about the same proportion that had a bachelor’s in 1960. Master’s mania began to spread through the higher-education world in the later 1990s, but it picked up steam during the Great Recession, even more than the bachelor’s did. From 2000 to 2012, the number of M.A.s granted annually jumped 63 percent; bachelor’s degrees rose only 45 percent. In 2000, higher-ed institutions granted an already-impressive 457,000 master’s degrees; by last year, the number had grown to 839,000. And while the Ph.D. remains a much rarer prize, its numbers have also been setting records. Some 45,000 new doctoral degrees were awarded in 2000, a number that, by last year, had more than doubled, to 98,000.

People find graduate degrees enticing for various reasons. Someone with a graduate degree will be more likely to find stable employment, will get more of a boost into higher-level positions than will B.A.s, will have bragging rights, and, most decisively, will earn fatter paychecks. Even as the growth of the college premium—the difference between expected earnings for a worker with a college degree and one with a high school diploma—shows signs of slowing down, the master’s premium has marched ever upward. According to “The Economic Value of College Majors,” a 2015 study by Georgetown University, college grads with a bachelor’s degree earn an average annual salary of $61,000 over their career. Strivers with a graduate degree can look forward to about $78,000. The earning advantage of college graduates over high school graduates increased only 6 percent from 2000 to 2013, but those with graduate degrees saw a 17 percent increase in their relative earnings over college grads.

The premium varies by field, of course. A master of fine arts (MFA) is a notoriously poor bet, though that doesn’t appear to have scared off many aspiring poets and painters (who tend to have wealthier parents). The number of MFAs has risen every year in the last decade, even though, in a number of states, early-career MFA recipients earn less than people with only an associate’s degree. Still, most fields can advertise a nice return for their students: a master’s in computer systems administration, for instance, will earn its beneficiaries a median annual salary of $88,000; a bachelor’s in that subject earns only $70,000. Education administrators see a 44 percent median boost if they get a master’s; preschool and kindergarten teachers, 43 percent; librarians, 30 percent; and flight engineers, 20 percent. Those who go to elite schools might earn somewhat more.

For individual students, a graduate degree can be a solid bet. For American society as a whole, though, hyper-credentialism has been a slow-motion disaster. The paper chase has put young people and their parents in a demoralizing, self-perpetuating arms race. Early in the twentieth century, high school diplomas were relatively rare and their recipients well compensated: in 1915, high school grads earned 45 percent more than dropouts. But by 1950, 59 percent of Americans were making it to the graduation ceremony. As the supply of high school–educated workers swelled, their wage premium fell to about 20 percent.

When every person has a high school diploma, the shrewd 18-year-old will find some other way to stand out. At first, this meant going to college. Today, however, a college degree is de minimis for high-paying jobs, so even college students need to look for ways to distinguish themselves. For a while, the double major served that purpose. These days, it won’t get you very far: the percentage of students at higher-ranked schools majoring in two different subjects is nearing half. In The Case Against Education, George Mason University economist Bryan Caplan likens the dynamic to people in the front row of an audience standing up to get a better view. That leads those behind them to stand, and those behind them, and so on. In the end, no one is better off.

This all-too-human behavior is a major force behind the master’s degree gold rush. With more college grads crowding the high-end labor market, the degree loses its prestige. As the college-wage premium weakens for recent graduates, students clamor for master’s degrees, and with a growing number of people with such degrees knocking on their doors, employers look at applicants with a bachelor’s as second class. A growing number of job listings include a master’s as the “expected or preferred level of entry,” particularly in STEM occupations and health care. In 2016, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicted that employment in master’s-level occupations would grow almost 17 percent by 2026.

The credential arms race is also a culprit in “elite overproduction.” Coined by Peter Turchin, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, the term refers to the excess number of job-searching college graduates compared with the positions in the high-paying managerial, technical, and professional vocations that they’ve been banking on. A lot of disappointed aspiring elites go back to school for postgraduate work; others take jobs that, in a different time, they might have gotten straight out of high school. The New York Fed reports that rates of underemployment—sometimes called “malemployment,” referring to grads working jobs that don’t require a college degree—have hovered between 40 percent and 50 percent since the 1990s; that’s more than 8 percentage points higher than for older grads. Ohio University economist Richard Vedder finds legions of “surplus elites” working as parking-lot attendants, bartenders, salespeople, and janitors.

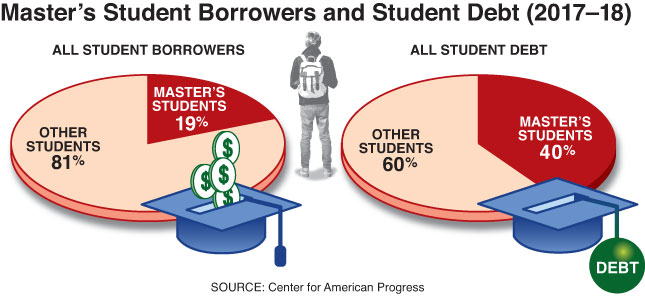

Postgraduate degrees are expensive, which usually means student loans. The financial burden falling on graduate students plays a far bigger role in the student debt crisis than people realize. The growth in the numbers of master’s degrees and Ph.D.s has closely paralleled the growth in student debt. Over the past 25 years, net tuition and fees have risen more steeply for master’s students than for undergrads. Though graduate students are only 19 percent of student borrowers, they account for 40 percent of student debt. Graduate students can borrow almost unlimited funds in unsubsidized loans, for which they will be burned by interest rates two times higher than those paid by undergrads. (The government pays interest for subsidized loans while a student is in school.) Twenty-five percent of graduate students borrow almost $100,000; 10 percent of them borrow more than $150,000. Many will have a ball and chain of debt following them for years, even decades, of their adult lives—which, as we’re now witnessing, leads to demands for new government programs.

College graduates may have plenty to dislike about the arms race, but the biggest losers are workers at the bottom of the labor market. The more credentials, the less hope for the child of a single mother who works as a health-care aide or for a father disabled in a mining accident. The more time and money needed to get a mid-skilled job, the more likely that people will give up and continue packing orders at an Amazon warehouse. Degree inflation widens the nation’s class divide.

Research by Julie Posselt and Eric Grodsky shows that, as of 2010, 45 percent of people with a master’s degree or higher came from families in the highest income quartile. Twenty years earlier, that figure was only 30 percent. “Educational inheritance is striking not just at the college level,” they write. “Those from homes in which the more educated parent had a doctorate or professional degree are increasingly overrepresented” among those who get Ph.D.s and professional degrees. “Their share of the top 1 percent of the income distribution is greater still, at 62 percent,” they write. The rich get richer; they also get Ph.D.s, M.D.s, and J.D.s. Meantime, the other two-thirds of Americans get a high school diploma or, at best, an associate’s degree.

Those who do find a way to continue up the degree ladder pay a high price. First, consider the opportunity costs: while they’re sitting in a statistics classroom, they aren’t earning money to take care of younger siblings, grandparents, and perhaps children of their own. The more direct costs, of course, are tuition and living expenses. The prospect of debt deters low-income students from pursuing degrees that could lead them to a lucrative career, according to a 2020 paper, “Inequality and Opportunity in a Perfect Storm of Graduate Student Debt.” Those who do take out loans for a degree start off their careers in the red, which can suppress wealth accumulation. About half of all master’s and Ph.D. students drop out before completing their degrees; the numbers are higher for those in the humanities and for racial minority and lower-income students. Dropping out often means the worst of both worlds: plenty of debt but no degree to show for it.

Worse still, credential inflation is squeezing less educated young adults out of jobs on which they once relied. Many jobs were available to high school grads only a decade or two ago but now demand at least a four-year degree, bringing more despair in working-class communities and more polarization in the country. According to the Wall Street Journal, more than 40 percent of manufacturing workers now have a college degree, up from 22 percent in 1991. Experts predict that college-educated workers will fill more than half of American manufacturing positions within the next three years.

Mid-skilled non-factory jobs are becoming equally inhospitable to someone without the means or interest to spend four more years (at a minimum) in a classroom. The Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education, for example, plans to increase entry-level degree requirements for occupational therapy assistants from an associate’s to a bachelor’s degree and to raise the requirement for full-fledged occupational therapists from a bachelor’s to a doctorate. Respiratory therapists might still squeak by with an associate’s degree in smaller markets, but the American Association of Respiratory Care is also proposing such a shift. Of the two nursing accrediting organizations, one permits an associate’s for practical nurses, but the other accredits only bachelor’s and master’s degree programs. Ohio University’s Vedder cites a quip predicting that within a decade or two, a master’s degree in “janitorial studies” will be needed to get a job as a custodian.

What’s driving this hyperactive credentialism? Why would young people want to prolong their years in a droning classroom at so much cost to themselves? Why would employers be willing to pay more for workers if they don’t have to?

The most benign answer is the most widely repeated: jobs require more education in today’s high-skilled economy. Postgraduate degrees in computer and biological sciences are among the most sought after; in both fields, students must deal with complex new technologies, specialties, and innovations. The numbers of master’s and Ph.D.s in nursing have exploded for similar reasons. Nurses don’t just train to take pulses and monitor blood pressure; they specialize in anesthesia, sports medicine, management, research, pediatrics, and midwifery, among other areas. In 2004, a mere 170 nurses received a doctor of nursing degree from a mere four schools. Fifteen years later, 357 schools awarded the degree to 7,037 students, with another 36,000 in the pipeline. Another 124 schools are in the planning stages, and, given the army of aging baby boomers, more will undoubtedly be needed.

But increasingly complex technological skills are only one part of a destructive feedback loop—in which colleges and universities, students, employers, unions, and meritocratic anxiety mutually reinforce one another.

Universities are the prime mover. Over the past decades, many have struggled to balance their books amid state cuts, regulatory requirements, and a customer base resistant to hikes in already obscene tuitions. Graduate programs are a good answer to the cash shortage: graduate students ease the strain on expensive infrastructure, they generally don’t need dormitories, and they often prefer evening, part-time, or online classes. Between 2008 and 2016, the share of students pursuing a master’s degree entirely online tripled, from 10 percent to 31 percent. After the Covid-19 pandemic, those numbers will likely rise. Graduate students can borrow considerably more federal money than undergrads can, and they don’t create the same level of inter-institution competition, relieving pressure for elaborate gyms, student centers, and other amenities. “Master’s degrees represent the strongest opportunity for revenue growth for many institutions,” promises a report from EAB, a university advisory firm. The market for the master’s, the organization estimates, adds up to a hefty $43.8 billion.

Small wonder that higher-ed institutions have embarked on a graduate program development spree. According to the Urban Institute report “The Rise of the Master’s Degree,” the number of distinct master’s fields granting at least 100 degrees per year rose from 289 in 1995 to 514 in 2017. Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, describes the process: “Educators say: ‘Let’s offer a program in this. Let’s offer a program in that.’ If they can get students to sign up, it’s a money-maker. . . . Every institution, especially universities, has to offer every credential. And if somebody down the road invents a new one, they have to replicate it.” He adds a surprising afterthought: “All this goes on with no actual proof of outcome.”

Master’s disciplines are often divided into subspecialties that may or may not actually prepare people for available jobs. You don’t just get a master’s in computer science, for example; you get a degree in AI, video-game design, machine learning, “human–computer interaction,” cloud computing, cybersecurity, data science, digital-interactive media, information systems, hardware and computer architecture, medical image computing, or something else. Degrees in the health sciences swell master’s course catalogs into the size of a 1940 New York City telephone book. At George Washington University, one can choose among degrees in clinical operations and health-care management, clinical research administration, clinical and translational research, correctional health administration, health-care quality, regulatory affairs, and biomedical informatics, among others.

University postgraduate catalogs are like curiosity shops that reflect administrators’ marketing calculations as much as student need or aspiration. Consider just a few of the curios for sale: a master’s of planning and management of natural hazards at the University of New England; a master’s in outdoor adventure and expedition leadership at Southern Oregon University; the University of Arizona offers a master’s in racetrack industry. Vincennes University in Indiana had a bowling management master’s that was axed in 2015. (Apparently, millennials and Zoomers find bowling too analogue.) Even the most classroom-avoidant students might stop to consider a master’s in sexuality studies at San Francisco State University. Visual and performing arts departments have been at the drawing board as well: Iowa State University gives an MFA in “creative writing and environment,” and New York University and Boston University offer video-editing degrees. Try the University of Connecticut if you’re looking to get a higher degree in puppetry. Arts-management programs are as easy to find as a McDonald’s. Florida State University offers a unique museum education and visitor-centered curation degree. Also popular are master’s degrees (or Ph.D.s) in student affairs for people who want to, among other things, advise students whether to get a master’s (or a Ph.D.). Can a master’s in master’s degrees be far behind?

Doctoral studies have also taken a turn toward the puzzling. Ph.D. programs in recreation and leisure studies have popped up in almost every part of the country. The University of Utah has a Ph.D. program in parks, recreation, and tourism. Ph.D.s in enology—i.e., wine—are also popular. Michigan State University offers a Ph.D. in packaging (at the university’s School of Packaging). Less practical is the Ph.D. in the history of consciousness at Santa Cruz, though it could be useful for a career in radical activism—one of the early graduates was Huey Newton, founder of the Black Panthers.

This is not to say that students in even the most curious-sounding programs aren’t learning anything. It’s just that they’re learning things that shouldn’t require prepping for the GRE, years of study for credits of dubious value, and sweat-inducing amounts of debt—not to mention a metastasizing higher-ed apparatus. In fact, today’s postgraduate structure is a relatively recent invention. Back in the day, postgraduate programs were a rarefied business designed to prepare students to become professors or to do high-level research at universities and pharmaceutical and technology companies. The point was to master a discipline, to add to its body of knowledge, and, if teaching, to pass it along to a new generation of students. Postgraduate academic work wasn’t something that the large majority of graduates going into white-collar jobs had any interest in. They knew that they could count on their employers to do the training.

No longer. For a long time, companies “hired for potential,” not for specific job skills, explains Peter Cappelli, Wharton professor of management and author of Will College Pay Off? Everyone understood that firms would train new employees who would stay on until it was time to receive the proverbial gold watch at the retirement party. Companies didn’t do much outside recruitment, since almost all hiring for more senior positions occurred in-house. The mutually satisfying arrangement fell apart in the 1980s as companies started restructuring and laying off workers. Executives concluded that training was a disposable and risky expense. Cappelli quotes one executive asking: “Why should I train my employees when my competitors are willing to do it for me?”

Universities jumped into the vacuum. The potential for new sources of income sent them scurrying to design novel products to compensate for the business sector’s retreat. That helped transform campuses into “training machines for American industry at the high-skill end,” as Katherine Newman, formerly a dean at Johns Hopkins University, has put it. Universities add new courses and degrees to satisfy a chronically shifting labor market, whether or not they know exactly what companies will be looking for. Even worse, the new system passed along the substantial cost of early-career training to young adults at a point in life when their parents and grandparents would have been earning a paycheck, starting a family, and buying a home. Now, barring a cushy trust fund, their kids are poring over the terms not of mortgages but of student loans.

How much of this “up-credentialing” reflects a genuine need for higher-level skills that can be learned only in a university classroom? Surely some of it. Advanced manufacturing really does require workers who understand advanced math and physics and who can do sophisticated coding for machines and robots.

But perverse market forces are at play, too. Employers tend to increase degree requirements when they have plenty of candidates to choose from—that is, when unemployment is high—because they can, not because of productivity. Employers, universities, and students seem to have convinced themselves that credentials are a proxy for skills. But as the Urban Institute’s Robert Lerman, perhaps the country’s leading specialist on apprenticeships, observes, that is an academic’s understanding of “skills.” It doesn’t describe much of the flexible problem-solving, careful focus, and experience that trade workers—or, say, occupational therapists—need in order to do their jobs well.

A 2014 study by Burning Glass Technologies, an analytics software company, supports the idea that, in many cases, up-credentialing has nothing to do with hard skills. The report discovered a large gap between the degree qualifications listed in help-wanted ads and the degrees held by those already employed. Sixty-five percent of online postings for executive assistant and secretarial positions, for example, required a bachelor’s, even though only 19 percent of those currently doing those jobs had the degree. Another study found that job descriptions requiring a bachelor’s often look virtually identical to those that don’t. Most large firms now use automated hiring software that simply filters out people without a college degree, no matter their relevant experience. It doesn’t seem to matter that it takes longer to find a new employee with a degree than one without, that it will cost the company 11 percent to 30 percent more in salary and benefits, and that employers often find that nongraduates with experience perform nearly as, or equally, well.

And don’t forget status. Every organization, from the Senate to the local McDonald’s, has its hierarchy; but higher education, the linchpin of meritocracy, increasingly shapes American status. Its intricacies could fill the residents of the House of Windsor with envy: adjunct, instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, professor, university professor, chaired professor, non-tenure track, tenure track, tenured . . . not to mention the de facto prestige rankings of the institutions themselves and the degrees they bestow on aspiring workers. Education has become central to sorting America’s young people into their proper socioeconomic position, and few educated people are immune to the glamour of the right degree from the right university.

Which brings us back to l’affaire Dr. Biden. One of the striking, though unspoken, facts about the controversy was the déclassé reputation of the degree that was the object of the dispute. Among the academic cognoscenti, schools of education are generally looked down on as the barefoot country cousin of the arts and sciences. In knowledgeable circles, the Ed.D., the diploma proudly claimed by the First Lady, was not something to brag about. H. L. Mencken, who never spared a rotten word for American education, reserved particular scorn for schools of education, or “normal schools,” as they were known at the time: “What you will find is a state of mind that will shock you. It is so feeble that it is scarcely a state of mind at all,” he snarled in a 1928 essay. Biden had already collected two master’s degrees before she began her doctoral work at the University of Delaware. Ed.D. training would not improve her teaching, since the program is largely for people pursuing careers in school administration. She couldn’t have been doing it for the money. So what was the point?

According to her husband, she wanted the degree because she liked the title.

“She said, ‘I was so sick of the mail coming to Senator and Mrs. Biden,’ the president has recounted. ‘I wanted to get mail addressed to Dr. and Sen. Biden.’ That’s the real reason she got her doctorate.” Dr. Biden might not fully agree with this account, but the foofaraw over Epstein’s article suggests that her real goal was what she wrongly imagined to be a respectable place in the meritocratic hierarchy.

This is not to say that postgraduate education is nothing more than an exercise in social climbing; social climbing is built in to the system that’s supposed to prepare graduates for adult life. Unlike a Ph.D., a master’s won’t get you called “Dr.” But degrees stratify groups by their very nature. A master’s in business administration may not be much to brag about to outsiders, but it signals higher rank, however modest in the scheme of things, to the mere B.A.s at office meetings. Nurses might pursue higher degrees for good reasons—more challenging work, more control over work hours—and they may not care about status at all. But prestige cares about a Ph.D.

Degrees determine whether you can write prescriptions, conduct research, manage and teach other nurses, and shape hospital or public-health policy, or whether you can simply take patients’ temperature and pulse, change bandages, and file paperwork. These differences shape people’s understanding of their place in a given hierarchy. They also determine whether you can be called “Dr.,” an honorific that confuses outsiders. In fact, M.D. organizations have fought for sole possession of the title in clinical settings and have persuaded legislators in some states to pass laws to that effect.

“Biden wants to provide 17 free years of education. That’d be like adding four stories to a crumbling building.”

One final force driving hyper-credentialism: the profound failure of our K–12 system. Complaints about the dearth of workplace-ready high school grads suffuse employer surveys. The kids are grammatically illiterate; they stutter and look at their feet during interviews; they don’t come to work on time or finish a project as scheduled. In a Burning Glass survey of mid-skilled companies, one HR staffer explained: “There’s something that comes with being a college student, a lot of maturity and knowing how to work with different people. They know how to communicate and to express themselves.” High school graduates should know how to communicate and to express themselves, to cooperate within a team, and to follow through on assignments. But they don’t.

The Biden administration wants government to provide 17 free years of education. That’d be like adding four stories to a crumbling building. A recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper shows that college GPAs have been rising since the 1990s, as have college graduation rates. The authors conclude that grade inflation is behind both trends. Colleges may think that they’re doing their students a favor by making it easier for them to get their diplomas; they’re actually just intensifying a credential arms race. Poorly educated college grads mean more master’s students, more student debt, and more years of quasi-adult status. Those who don’t go to college will never be able to achieve the polish that their school systems have failed to demand of them.

Jeremiads about higher education’s role in perpetuating inequality almost always include recommendations for more career and technical education and apprenticeships for kids for whom the college-for-all model is not working. I won’t break the pattern. The next generation desperately needs these alternatives, and parents want them. Gallup found that 46 percent of parents prefer other secondary options “even if there were no barriers to their child earning a bachelor’s degree.” Yet those parents say that they don’t hear much about such options; it’s always college, college, college. In a plea for more “work-based programs” for non-college-graduating kids—remember, that’s two-thirds of them—Annelies Goger of the Brookings Institution points out that federal funding for public colleges and universities was $385 billion in 2017–18, compared with $14 billion for employment services and training. The math doesn’t make sense.

The kids who could benefit most from work-based programs will never be called “Dr.” Maybe that’s not such a bad thing.

Photo: Recent college graduates are having a harder time in the job market as the value of a bachelor’s degree declines. (JOSE LUIS MAGANA/REUTERS/NEWSCOM)