At the end of March, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rolled back Obama-era fuel economy standards projected to add nearly $3,000 to the cost of a new car. It was the latest instance of President Trump’s record of cutting excessive regulations, which he describes as “stealth taxation, especially on the poor.” Trump’s deregulatory actions over the past three years will increase the purchasing power of working-class income by up to 15 percent, at least after the Covid-19 pandemic passes and the economy begins functioning again. The current economic depression from the pandemic underscores the importance of removing obstacles to economic advancement for those most in need of it.

One of the best-kept secrets in the economics of regulation is how regulation’s costs fall disproportionately on the poor. “Well-intentioned regulation often indulges the preferences of the wealthy,” observes Creighton University professor Diana Thomas. By “driving up the prices of regulated goods and lowering the wages of lower income households and workers, such regulation is likely to have disproportionately negative or regressive effects on the poor.”

Trump’s 2020 reelection drive will likely position itself on the side of the poor and middle class, while portraying his likely Democratic opponent, former vice president Joe Biden, as a representative of the entrenched bureaucratic class that oversaw accelerated rulemaking during the Obama years. The historical trend has been toward ever-greater regulation, with all of Trump’s political competitors promising to restore that tradition and even exceed it.

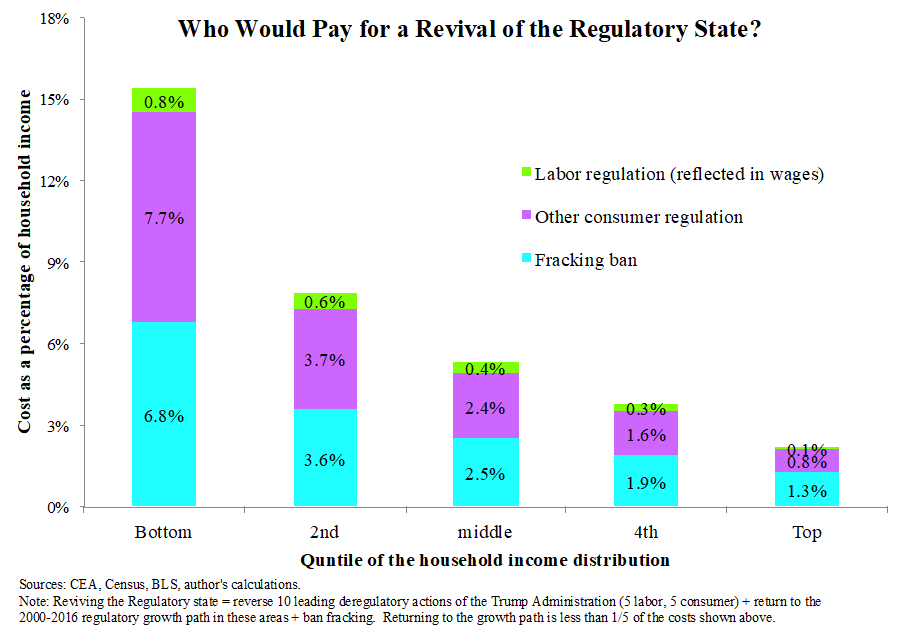

Who would pay most for a revival of the regulatory state? Dividing American households into five income groups from lowest to highest, I have estimated each group’s regulatory costs and expressed them as a percentage of its average income. The costs to the bottom quintile amount to 15.3 percent of their total income—representing as high a burden as all the taxes they currently pay. This group would experience part of the cost as lower wages, but the biggest bite would come in the form of diminished purchasing power due to higher prices for energy, cars, and other consumer goods. The top quintile, by contrast, would suffer the least from regulatory restoration, with labor, energy, and other consumer rules amounting to only a 2.2 percent implicit tax on the highest earners.

My analysis of a hypothetical revival of the regulatory state focuses on ten of Trump’s key deregulatory actions—five of which reverse employment regulations such as employer mandates—and on a revised definition of “joint employer.” These employment regulations held down productivity and wages and reduced job opportunities, especially for less-skilled workers. It’s no coincidence that Trump’s regulatory reversals coincided with an acceleration of wage growth in 2018 and 2019, with low-skill workers seeing the fastest gains.

The Trump administration has also revoked regulations that outlawed more affordable alternatives for Internet services, prescription drugs, and financial products, thus expanding consumer choice. Another move partially reverses the Obama administration’s minimum fuel-efficiency standards that added about $3,000 to the price of an average car, and even more to the price of cars that did not meet these standards. This environmental tax on driving is a significant burden for lower-income households.

Did these rolled-back regulations have any benefits? Certainly—to large banks, trial lawyers, major health-insurance companies, big tech companies, and foreign drug manufacturers that profit when consumers must buy their expensive products because affordable alternatives are not available.

Not only has Trump removed hundreds of regulations; he has slowed the pace of adding new ones, compared with prior administrations. The chart above therefore also includes the costs of a revival of the regulatory state, by which I mean returning to the prior trend in the same employment-, consumer-, and energy-regulation areas. Finally, the chart also shows the costs of banning fracking—another policy pursued by pre-Trump regulatory regimes—which would increase consumer prices for electricity, heat, and gasoline.

These estimates are conservative because I have excluded many significant deregulatory actions from the analysis. For instance, I did not include the removal of health-insurance regulations, including the individual mandate and prohibitions against “junk” insurance plans, or plans that are affordable because they permit healthy people to opt out of unneeded coverage. The estimates also exclude costly state and local regulations that, according to estimates by the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA), increase metro-area homelessness by 44 percent.

Children once learned the tale of how the poor of Sherwood Forest were abused by taxation by the rich, giving rise to Robin Hood’s campaign to reverse the injustice. Scholars still argue whether a real Robin Hood actually existed, but the record shows that President Trump’s assault on the regulatory state is helping the working poor keep more of their money.

Photo by Sean Rayford/Getty Images