Some longtime Californians view the continued net outmigration from their state as a worrisome sign, but most others in the Golden State’s media, academic, and political establishment dismiss this demographic decline as a “myth.” The Sacramento Bee suggests that it largely represents the “hate” felt toward the state by conservatives eager to undermine California’s progressive model. Local media and think tanks generally concede the migration losses but comfort themselves with the thought that California continues to attract top-tier talent and will remain an irrepressible superpower that boasts innovation, creativity, and massive capital accumulation.

Reality reveals a different picture. California may be a great state in many ways, but it also is clearly breaking bad. Since 2000, 2.6 million net domestic migrants, a population larger than the cities of San Francisco, San Diego, and Anaheim combined, have moved from California to other parts of the United States. (See Figure 1.) California has lost more people in each of the last two decades than any state except New York—and they’re not just those struggling to compete in the high-tech “new economy.” During the 2010s, the state’s growth in college-educated residents 25 and over did not keep up with the national rate of increase, putting California a mere 34th on this measure, behind such key competitors as Florida and Texas. California’s demographic woes are real, and they pose long-term challenges that need to be confronted.

The state has suffered net outmigration in every year of the twenty-first century, but its smallest losses occurred in the early 2000s and the years following the Great Recession, when housing affordability was closer to the national average. Home prices have risen since then—and so have departures. Between 2014 and 2020, net domestic outmigration rose from 46,000 to 242,000, according to Census Bureau estimates.

The outmigration does not seem to have reached a peak. Roughly half of state residents, according to a 2019 UC Berkeley poll, have considered leaving. In Los Angeles, according to a USC survey, 10 percent plan to move out this year. The most recent Census Bureau estimates show that California started falling behind national population growth in 2016 and went negative for the first time in modern history last year.

The comforting tale that only the old, bitter, and uneducated are moving out simply does not withstand scrutiny. An analysis of IRS data through 2019 confirms that increasing domestic migration is not dominated by the youngest or oldest households. Between 2012 and 2019, tax filers under 26 years old constituted only 4 percent of net domestic outmigrants. About 77 percent of the increase came among those in their prime earning years of 35 to 64. In 2019, 27 percent of net domestic migrants were aged 35 to 44, while 21 percent were aged 55 to 64. (See Figure 2.)

To be sure, the largest increase in net domestic migration was among those aged 65 and over. But the second-largest increase came in the 25 to 34 categories—with the state’s exorbitantly high cost of living the likely culprit.

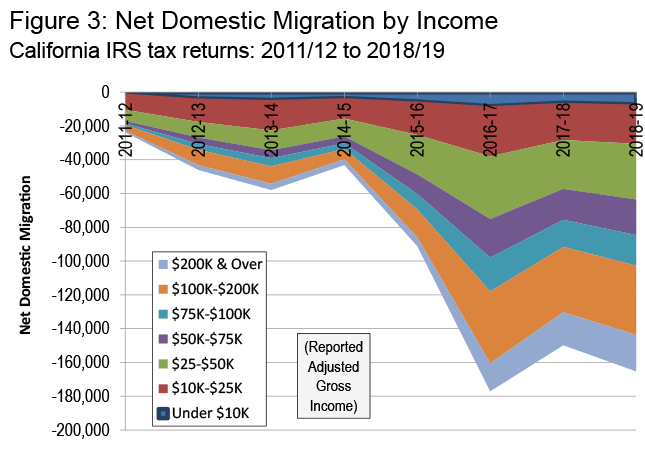

Nor is it primarily an exodus of the poor driving the trend. Of the increased net domestic migration from 2012 to 2019, only 14 percent came from those in the under-$25,000 income category. Those with higher incomes accounted for 82 percent; indeed, 38 percent of the increase came among the over-$100,000 category. (See Figure 3.)

In fact, the largest increases in net domestic outmigration from 2012 to 2019 came from the top four income categories ($50,000 to $75,000; $75,000 to $100,000; $100,000 to $200,000; and over $200,000).

Most alarming has been the loss of the young, who have traditionally driven the state’s innovative, entrepreneurial economy. In fact, Los Angeles between 2012 and 2017 ranked behind only New York City for the largest net losses of millennials, notes the Brookings Institution. Many younger people who traditionally headed to California, notes Brookings, now choose Dallas-Fort Worth, Seattle, Austin, Houston, or Denver.

The foreign-born population, which for years floated California’s demographic boat, appears to have had a change of heart. In the last decade, according to a recent study we conducted for Heartland Forward, Los Angeles suffered a net decline in the foreign-born, while such rivals as Dallas-Fort Worth, Nashville, Houston, Phoenix, and Las Vegas enjoyed double-digit growth—with gains that approach 30 percent.

These patterns contribute to a plummeting birth rate. As people at peak age for family formation leave, Los Angeles and San Francisco rank last and second-to-last in birthrates among the 53 U.S. major metropolitan areas. In California, only Riverside/San Bernardino exceeds the national average in births among women aged 15 to 50, according to the 2014–2018 American Community Survey. Since 2007, the fertility rate across the country has fallen from 2.1 to 1.6, but California’s rate fell faster—from 2.2 to about 1.5, spanning race and ethnicity. Notably, Latina women experienced the largest decline in California and now have below-replacement fertility.

California was once seen as a paragon of youthful energy, but it is gradually ditching the surfboard and adopting the walker. From 2010 to 2018, California’s population aged 50 percent more rapidly than the rest of the country, according to data from the American Community Survey. By 2036, seniors will be a larger share of the state’s population than will people under 18.

Golden State businesses likely will face a severe shortage of skilled graduates, as baby boomers retire and the new generation moves elsewhere. In 2015, over 50 percent of all jobs in California could be classified as middle-skill, but only 39 percent of the state’s workers were trained at that level. Demand for these competencies should remain robust in the coming decade. A study from the Public Policy Institute of California says the state will need approximately 1.1 million more college graduates by 2030 and projects that the demand for graduates by then will exceed the supply by 5.4 percent.

The pandemic-driven shift to online and dispersed work has further eroded the once-unchallenged attractiveness of California cities for tech and other skilled workers. Such leading tech firms as Facebook, Salesforce, and Twitter now expect a large proportion of their employees to continue to work remotely after the pandemic and have announced policies to facilitate these preferences. Some three-quarters of venture capitalists and tech-firm founders, notes one recent survey, expect to operate totally or mostly online. Since the pandemic began, according to a study by Big Technology, tech growth has been most evident in metros like Madison, Wisconsin; Cleveland; and Hartford, while New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, Boston, and Chicago have declined.

Tech bigwigs, not to mention property owners in San Francisco, may try to force a return to the mothership. But Apple CEO Tim Cook’s haughty demands for people to go back to the office received immediate blowback from workers, reflecting national sentiments. In a recent survey of more than 5,000 employed adults, four in ten American workers expected some level of remote-work flexibility after the pandemic.

A recent report from Upwork finds that between 14 million and 23 million Americans are looking to move to less expensive, less crowded places. Los Angeles and San Francisco have been losing migrants at an accelerating rate; L.A. County, the nation’s largest county, lost 745,000 net domestic migrants over the decade. Other areas, including parts of the Central Valley and the Inland Empire, have enjoyed higher population and job growth. But the hottest growth may be in the Sierra counties, which offer bucolic, scenic locales ideal for knowledge workers fleeing dysfunctional cities.

In past cycles, California accommodated growth largely by expanding its urban footprint. But the state’s ever-more draconian regulatory regime, seeking to limit “sprawl” to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions from cars, has driven up land prices and inhibited the growth of desired suburban alternatives. These policies—as well as delayed regulatory approvals, zero-emissions mandates, and mandatory solar power—have made building new homes, particularly single-family ones, a huge challenge. During 2020, when national house construction grew 6.1 percent from 2019, California’s rate declined 3.7 percent, according to Census Bureau data. Over the same period, Texas homebuilding increased 9.8 percent, Florida 6.3 percent, Arizona 29.5 percent, and Tennessee 20 percent. California’s housing construction in 2020 was its lowest since 2016.

Regulations favoring densification, particularly in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, have not prevented those areas from having the nation’s highest-priced housing. California also has the nation’s highest urban density and increased the most in the last decade at an incremental rate of 11,000 people per square mile—a density comparable to that of the city of Chicago—and 5.5 times the national rate. Yet prices relative to incomes have grown far faster than in the rest of the country, including in such thriving areas as Dallas–Ft. Worth and Austin, where prices remain far lower. Housing, according to a recent Berkeley poll, was by far the biggest factor cited by people wanting to move.

As the state’s media and academic apologists point out, California has bounced back before. Yet if the state has recovered from its most recent slump, it has done so in increasingly unequal fashion. California has the fifth-highest Gini Inequality index in the nation in 2019, according to American Community Survey data—not to mention the highest rates of cost-of-living-adjusted poverty (even worse than Mississippi or West Virginia), the worst housing affordability in the continental U.S., and a devastating shortage of mid-skilled workers. These factors may not affect the state’s elite, but they could persuade middle class families to move out—or not to come in the first place.

The Golden State has emerged from the pandemic flush with money from Washington and a spate of IPOs but suffering from the highest unemployment rates, continued corporate flight, and deteriorating social conditions in its big cities. This is not the California of the “dream” but a declining state for all but the most favored and those most dependent on government subsidies. The political establishment may continue to deny what is happening, but unless the state confronts some unpleasant facts and shifts direction, California’s demographic decline will likely continue.

Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images